Conclusion To Series On The Dawn Of Everything

Posts on The Dawn Of Everything: Link

The Dawn Of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow has 525 pages of text. I’ve discussed 10 of the 12 chapters in the last 14 months, and it’s time to move on. I’ll conclude this series with a few ideas triggered by the book.

1. The authors show that human societies didn’t follow any particular pattern of change. We didn’t move from foraging to agriculture to industrialization along a single track. We didn’t grow from bands to tribes to clans to small hamlets to towns to cities to nation-states. We didn’t move from one form of social organization to another in any particular order. Instead, the crucial factor is human agency. Agency is the antithesis of the mindlessness of Darwin-style evolution. People make choices. Genes don’t.

2. Greaber and Wengrow are clear about their biases. Among other things they think the current state of society is based on social inequality, and that this is bad. One of the principle themes of the book is laid out as a section heading at p. 111: Why The Real Question Is Not “What Are The Origins Of Social Inequality’ But ‘How Did We Get Stuck?’ They don’t answer the question directly, but it’s likely they think one of the central problems is domination.

In Chapter 10 they say that societies are held together by domination, which can take three forms, sovereignty (control of violence), control of knowledge, and charisma, which operates through virtues approved by the group, such as strength or rhetoric. Each of these can be used to achieve and perpetuate social inequality.

3. The authors think that societies have a shared mental component that links members and separates them from other groups. In ancient societies people shared creation myths or other cosmogonies, rituals, cultic practices, totems, and social practices. We moderns do too. In this post I suggested that

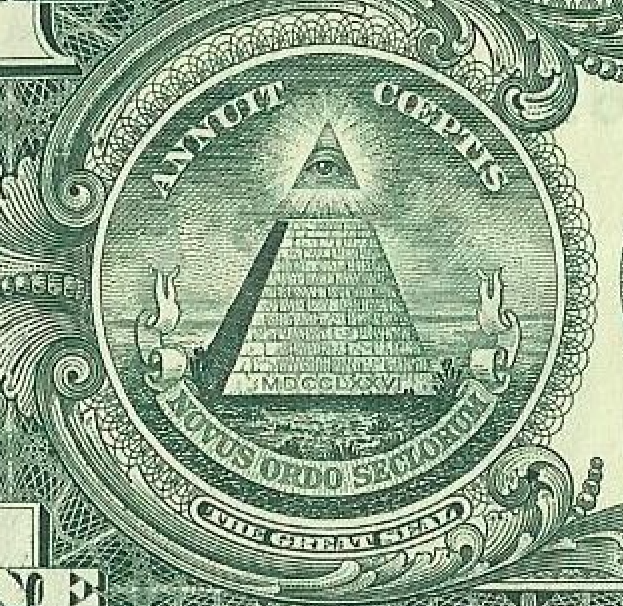

… we Americans share a sort of secular religion based on the founding myths of our country and a weak allegiance to what Jefferson called “Laws of Nature and Nature’s God” in the Declaration of Independence. The latter is a formulation that originally meant Natural Law but I think now includes a science-based mental stance and values based on a vaguely Christian moral sense. The founding myths include our commitment to freedom, as “all men are created equal”; a government of laws, not of men; a form of capitalism; and representative democracy.

By “vaguely Christian moral sense”, I meant something like the Golden Rule, and that this Rule was given to us from something greater than our mortal selves. Each of us has many more beliefs, some fully supported by fact and reason, many less so, and some perfectly arbitrary, such as a preference between forks and chopsticks, or certainty that the end times are upon us.

One important mental component that holds citizens of the US together is a shared commitment to the idea that this is a nation of laws, not of men. We had a general agreement that we would select our leaders, and adhere to the laws and rules they enacted. There’s still some truth there even in these days of Republican treachery.

4. Control of knowledge is a powerful tool. In Chapter 10 the authors describe an ongoing problem in pre-dynastic Egypt, around 3500 BCE: whether the dead require food and drink, and if so, what. The answer turns out to be they need leavened bread and wheat beer. There is no known explanation for this. Skeptics might suggest the priests who gave this answer really liked leavened bread and wheat beer. In any event, this answer required a vast increase in the amount of wheat to satisfy the needs of all of the dead people. That led to vast increases in agriculture, away from the fertile floodplains of the Nile, increased need for irrigation, additional labor, accounting bureaucracies, and debt peonage. The baseless idea of feeding the dead changed the course of human history.

Many of the societies described in the book believed that their gods demand sacrifices of animals, food, or even human beings. We see this among the Aztecs, and in Gen. 4:3 and Gen. 22:2, for example. These ideas don’t ever really disappear. For example, the idea of helping one’s dead ancestors shows up in Chinese use of joss paper.

These ideas seem strange to me, even for the ancients. That’s because they are perfectly abstract. There is no way to verify them, or to justify them other than stories. And yet human beings have always acted on stories, and those actions shape whole societies.

5. At present, it seems to me that our mutual commitment to the rule of law is threatened by a drive to dominate and control knowledge. In most advanced societies knowledge was largely generated and vetted in and through an academic culture. Because of this commitment, no one cared that I read existentialist and surreal texts in college in the 60s, and no one cared that my history class was heavy on criticism of Gilded Age capitalism. Everyone assumed that it was important that as we got older we replace our child’s version of philosophy and of our history with a more adult ideas. Universities were thought to be the training grounds for leadership. Why would you want ignorant leaders, trained on a bunch of Young Adult stories?

But now intellectual pursuits, such fields of study as Critical Race Theory, deconstruction, the history of Reconstruction in the US, and gender studies are the subject of political hostility. For at least the last 50 years private interests have been trying to take control of information. Think of tobacco companies and their scientists lying about their cancer-causing products. Exxon and its scientists concealed the dangers of climate breakdown while fighting changes in energy policy. Someone found a bunch of doctors to attack vaccines. The right-wing media dumps lies into the minds of its audience. Now politicians are reaching directly into the intellectual formation of college students, hoping to hide people and histories they don’t like and that don’t fit the Potemkin World they’ve created.

That Potemkin World is the endpoint sought by the reactionaries who have dumped billions into the project of knowledge control. They’re motivated by their desire to protect and extend their wealth, and defuse any opposition to their control. I see an obvious analogy to the priests of Egypt who divined that the dead needed wheat beer.

Graeber and Wengrow say “As soon as we were human we started doing human things.” P. 82. And apparently we keep doing them even when they make as little sense as feeding the dead with expensive wheat products or risking the future of the earth to make a few bucks.