As I noted in this post, the government insists that it did not engage in parallel construction in the case of Shantia Hassanshahi, the Iranian-American busted for sanctions violations using evidence derivative of a search of what the government now claims was a DEA dragnet. “While it would not be improper for a law enforcement agency to take steps to protect the confidentiality of a law enforcement sensitive investigative technique, this case raises no such issue.”

The claim is almost certainly bullshit, true in only the narrowest sense.

Indeed, the changing story the government has offered about how they IDed Hassanshahi based off a single call he had with a phone belonging to a person of interest, “Sheikhi,” in Iran, is instructive not just against the background of the slow reveal of multiple dragnets over the same period. But also for the technological capabilities included in those claims. Basically, the government appears to be claiming they got a VOIP call from a telephony database.

As I lay out below, the story told by the government in various affidavits and declarations (curiously, the version of the first one that appears in the docket is not signed) changed in multiple ways. While there were other changes, the changes I’m most interested in pertain to:

- Whether Homeland Security Investigator Joshua Akronowitz searched just one database — the DEA toll record database — or multiple databases

- How Akronowitz identified Google as the provider for Hassanshahi’s phone record

- When and how Akronowitz became interested in a call to Hassanshahi from another Iranian number

- How many calls of interest there were

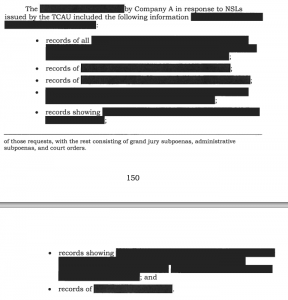

As you can see from the excerpts below, Akronowitz at first claimed to have searched “HSI-accessible law enforcement databases,” plural, and suggested he searched them himself. In July 2014, in response to a motion to suppress (and after Edward Snowden had disclosed the NSA’s phone dragnet), Akronowitz changed that story and said he sent a research request to a single database, implying someone else did a search of just one database. Akronowitz told the same story in yet another revised affidavit submitted last October. In the declaration submitted in December but unsealed in January, DEA Assistant Special Agent Robert Patterson stuck with the single database story and used the passive voice to hide who did the database query.

While Akronowitz’ story didn’t change regarding how he discovered that Hassanshahi’s phone was a Google number, it did get more detailed in the July 2014 affidavit, which explained that he had first checked with another VOIP provider before being referred to Google.

Perhaps most interestingly, the government’s story changed regarding how many calls of interest there were, and between what numbers. In January 2013, Akronowitz said “a number of telephone calls between ‘Sheikhi’s’ known business telephone number and telephone number 818-971-9512 had occurred within a relatively narrow time frame” (though he doesn’t tell us what that time frame was). He also says that his Google subpoena showed “numerous calls to the same Iranian-based telephone number during a relatively finite period of time.” He neither explained that this number was not Sheikhi’s number — it was a different Iranian number — nor what he means by “a relatively finite period of time.” His July and October affidavits said his research showed a contact, “on one occasion, that is, on July 4, 2011,” with Sheikhi’s number. The July affidavit maintained the claim that there were multiple calls between Hassanshahi’s number and an Iranian one: “numerous phone calls between Hassanshahi’s ‘818’ number and one Iranian phone number.” But by October, Akronowitz conceded that the Google records showed only “that Hassanshahi’s ‘818’ number made contact with an Iranian phone number (982144406457) only once, on October 5, 2011” (as well as a “22932293” number that he bizarrely claimed was a call to Iran). Note, Akronowitz’ currently operative story would mean the government never checked whether there were any calls between Hassanshahi and Sheikhi between August 24 and September 6 (or after October 6), which would be rather remarkable. Patterson’s December affidavit provided no details about the date of the single call discovered using what he identified as DEA’s database, but did specify that the call was made by Hassanshahi’s phone, outbound to Iran. (Patterson didn’t address the later Google production, as that was pursuant to a subpoena.)

To sum up, before Edward Snowden’s leaks alerted us to the scope of NSA’s domestic and international dragnet, Akronowitz claimed he personally had searched multiple databases and found evidence of multiple calls between Hassanshahi’s phone number and Sheikhi’s number, as well as (after getting a month of call records from Google) multiple calls to another Iranian number over unspecified periods of time. After Snowden’s leaks alerted us to the dragnet, after Dianne Feinstein made it clear the NSA can search on Iranian targets in the Section 215 database, which somehow counts as a terrorist purpose, and after Eric Holder decided to shut down just the DEA dragnet, Akronowitz changed his story to claim he had found just one call between Hassanshahi and Shiekhi, and — after a few more months — just one call from another Iranian number to Hassanshahi. Then, two months later, the government claimed that the only database that ever got searched was the DEA one (the one that had already been shut down) which — Patterson told us — was based on records obtained from “United States telecommunications service providers” via a subpoena.

Before I go on, consider that the government currently claims it used just a single phone call of interest — and the absence of any additional calls in a later months’s worth of call records collected that fall — to conduct a warrantless search of a laptop in a state (CA) where such searches require warrants, after having previously claimed there was a potentially more interesting set of call records to base that search on.

Aside from the government’s currently operative claim that it would conduct border searches based on the metadata tied to a single phone call, I find all this interesting for two reasons.

First, the government’s story about how many databases got searched and how many calls got found changed in such a way that the only admission of an unconstitutional search to the judge, in December 2014, involved a database that had allegedly been shut down 15 months earlier.

Maybe they’re telling the truth. Or maybe Akronowitz searched or had searched multiple databases — as he first claimed — and found the multiple calls he originally claimed, but then revised his story to match what could have been found in the DEA database. We don’t know, for example, if the DEA database permits “hops,” but he might have found a more interesting call pattern had he been able to examine hops (for example, it might explain his interest in the other phone number in Iran, which otherwise would reflect no more than an immigrant receiving a call from his home country).

All of this is made more interesting because of my second point: the US side of the call in question was an Internet call, a Google call, not a telephony call. Indeed, at least according to Patterson’s declaration (records of this call weren’t turned over in discovery, as far as I can tell), Hassanshahi placed the call, not Sheikhi.

I have no idea how Google calls get routed, but given that Hassanshahi placed the call, there’s a high likelihood that it didn’t cross a telecom provider’s backbone in this country (and god only knows how DEA or NSA would collect Iranian telephony provider records), which is who Patterson suggests the calls came from (though there’s some room for ambiguity in his use of the term “telecommunications service providers”).

USAT’s story on this dragnet suggests the data all comes from telephone companies.

It allowed agents to link the call records its agents gathered domestically with calling data the DEA and intelligence agencies had acquired outside the USA. (In some cases, officials said the DEA paid employees of foreign telecom firms for copies of call logs and subscriber lists.)

[snip]

Instead of simply asking phone companies for records about calls made by people suspected of drug crimes, the Justice Department began ordering telephone companies to turn over lists of all phone calls from the USA to countries where the government determined drug traffickers operated, current and former officials said.

[snip]

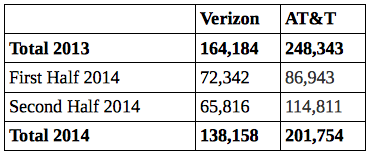

Former officials said the operation included records from AT&T and other telecom companies.

But if this call really was placed from a Google number, it’s not clear it would come up under such production, even under production of calls that pass through telephone companies’ backbones. That may reflect — if the claims in this case are remotely honest — that the DEA dragnet, at least, gathered call records not just from telecom companies, but also from Internet companies (remember, too, that DOJ’s Inspector General has suggested DEA had or has more than one dragnet, so it may also have been collecting Internet toll records).

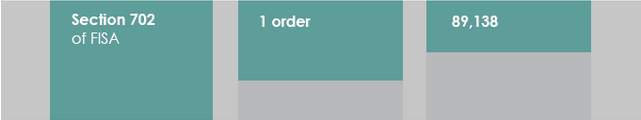

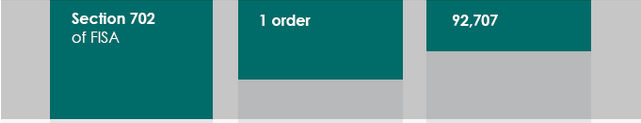

And that — coupled with the government’s evolving claims about how many databases got checked and how many calls that research reflected — may suggest something else. Given that the redactions on the providers obliged under the Section 215 phone dragnet orders haven’t changed going back to 2009, when it was fairly clear there were just 3 providers (AT&T, Sprint, and Verizon), it may be safe to assume that’s still all NSA collects from. A never-ending series of leaks have pointed out that the 215 phone dragnet increasingly has gaps in coverage. And this Google call would be precisely the kind of call we would expect it to miss (indeed, that’s consistent with what Verizon Associate General Counsel — and former DOJ National Security Division and FBI Counsel — Michael Woods testified to before the SSCI last year, strongly suggesting the 215 dragnet missed VOIP). So while FISC has approved use of the “terrorist” Section 215 database for the terrorist group, “Iran,” (meaning NSA might actually have been able to query on Sheikhi), we should expect that this call would not be in that database. Mind you, we should also expect NSA’s EO 12333 dragnet — which permits contact chaining on US persons under SPCMA — to include VOIP calls, even with Iran. But depending on what databases someone consulted, we would expect gaps in precisely the places where the government’s story has changed since it decided it had searched only the now-defunct DEA database.

Finally, note that if the government was sufficiently interested in Sheikhi, it could easily have targeted him under PRISM (he did have a GMail account), which would have made any metadata tied to any of his Google identities broadly shareable within the government (though DHS Inspectors would likely have to go through another agency, quite possibly the CIA). PRISM production should return any Internet phone calls (though there’s nothing in the public record to indicate Sheikhi had an Internet phone number). Indeed, the way the NSA’s larger dragnets work, a search on Sheikhi would chain on all his correlated identifiers, including any communications via another number or Internet identifier, and so would chain on whatever collection they had from his GMail address and any other Google services he used (and the USAT described the DEA dragnet as using similarly automated techniques). In other words, when Akronowitz originally said there had been multiple “telephone calls,” he may have instead meant that Sheikhi and Hassanshahi had communicated, via a variety of different identifiers, multiple times as reflected in his search (and given what we know about DEA’s phone dragnet and my suspicion they also had an Internet dragnet, that might have come up just on the DEA dragnets alone).

The point is that each of these dragnets will have slightly different strengths and weaknesses. Given Akronowitz’ original claims, it sounds like he may have consulted dragnets with slightly better coverage than just the DEA phone dragnet — either including a correlated DEA Internet dragnet or a more extensive NSA one — but the government now claims that it only consulted the DEA dragnet and consequently claims it only found one call, a call it should have almost no reason to have an interest in.

Read more →