The Fed Prepares To Screw Working People Again

The Federal Reserve Board has signaled its intention to hike interest rates, citing a fear of an overheated economy. Robert Reich has an opinion piece in The Guardian saying that raising interest rates will hurt working Americans. Reich explains; “They fear that a labor shortage is pushing up wages, which in turn are pushing up prices – and that this wage-price spiral could get out of control.” Reich explains why this is wrong.

The theory behind the Fed’s action is called the Philips Curve, which says roughly that as unemployment rises, inflation goes down, and vice versa, that as unemployment goes down, inflation increases. Here is a technical discussion of the history of the Philips Curve. This one is shorter and may be easier to read. They both say the same thing: there isn’t any obvious relation. The first piece describes some professional criticism of the Philips Curve which sadly has never had any impact on decision-making. The position of the economics profession apparently is that it must be right because they learned in in an advance economics course in College.

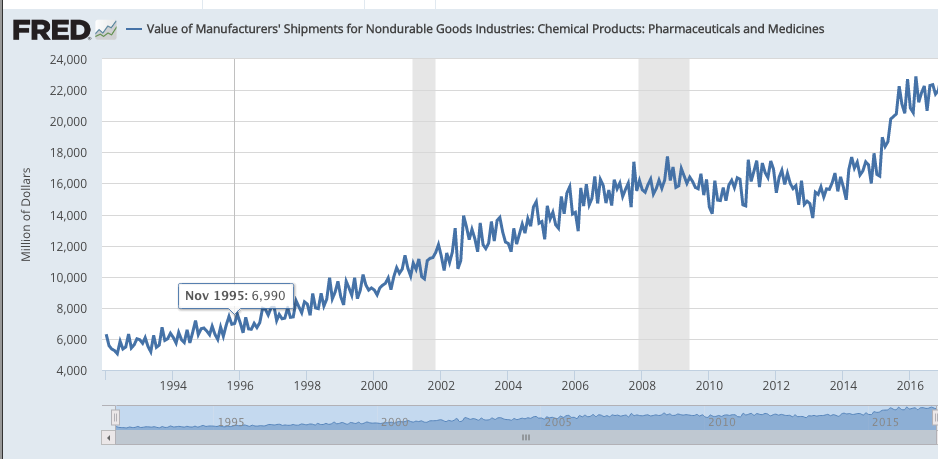

When you think about it, it’s utterly absurd: there are many sources of inflation, not the least of which is corporate pricing power. When most industries are highly concentrated in a few market participants they can set prices to maximize their profits. For example, Amazon dominates retailing. They just raised the price of their Prime service by $20 per household. There are about 150 million US subscribers. That’s about a $3 billion increase in revenues. Amazon blames wage increases and inflation for the increase. No, really. It comes on top of stupefying profits of $33.4 bn. So right there you get a huge increase in profits, vastly more than any wage increases or other inflationary costs.

Reich says that the impact of Fed interest rate hikes will fall on working Americans. As he puts it, “Higher interest rates will harm millions of workers who will be involuntarily drafted into the inflation fight by losing jobs or long-overdue pay raises.”

Let’s look at the numbers.

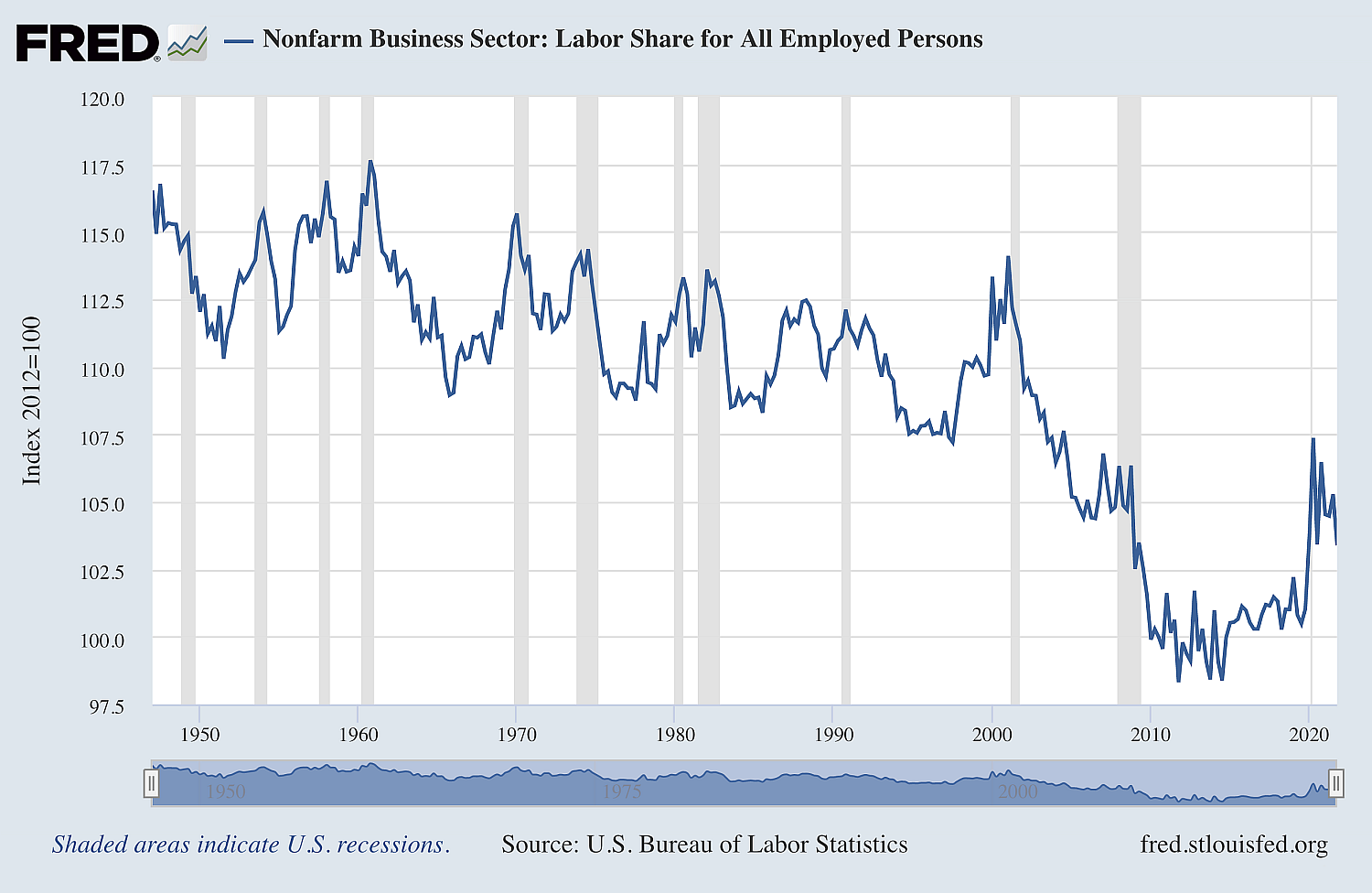

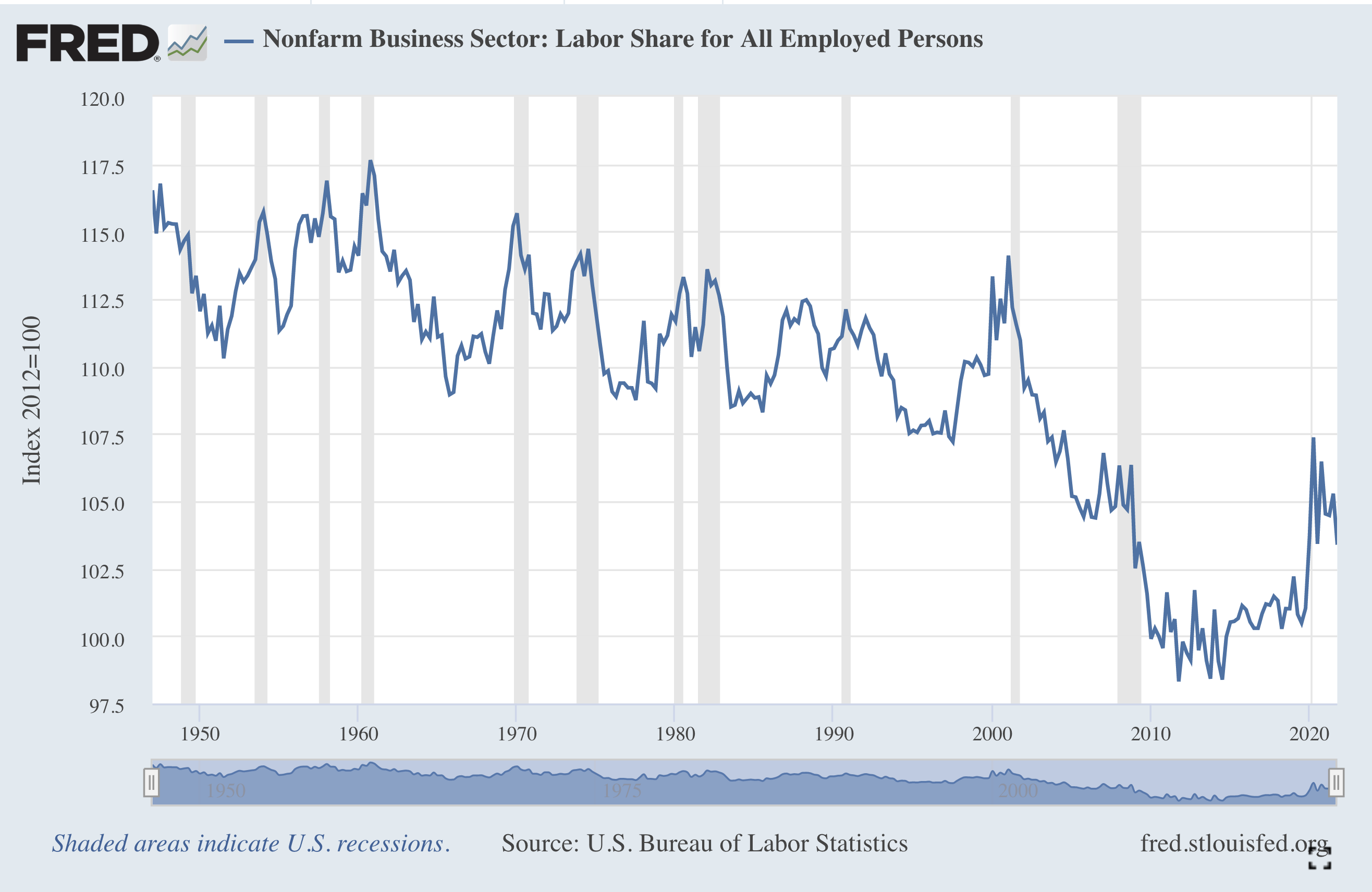

This chart shows the share of GDP going to labor*.

The gray bars are recessions. Almost all of the recessions since 1947 were triggered by interest rate increases. This chart says that when wages start to rise, the Fed raises rates, leading to recessions. Wage share falls. When it starts to rise again, the Fed triggers more rate increases. Before 1960, the labor share rose nearly to its previous highest levels. After 1960 the labor share peaks never reach their previous level.

The Great Crash led to a recession, one not caused by the Fed. In response, the Fed dropped interest rates to zero. But the labor share didn’t return to 2008 levels until 2020, and has fallen back since. Why does the Fed fear wages at this absurdly low share of GDP?

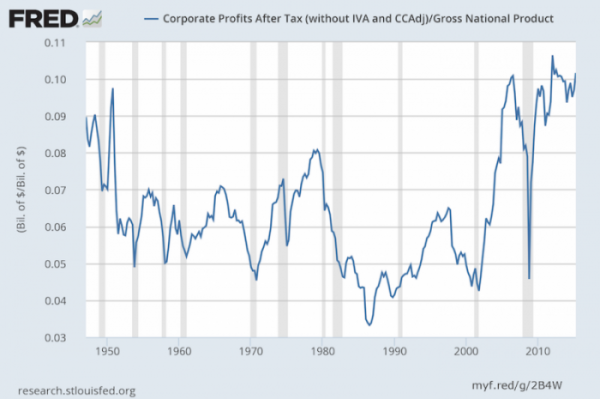

Now let’s look at corporate profits. This chart shows an estimate of corporate profits**.

The chart says that from 2012 to 2020, corporate profits were roughly steady at about $2.2 trillion. Then profits jumped straight up to the current level of $3.1 trillion in just two years. I’d guess the total rise is something like $1.4 trillion. That’s an astonishing increase. When did any media outlet point out that this is a major driver of inflation? Business reporters repeat the claims of corporate PR hacks that it’s all the fault of greedy American workers, or Covid, or supply chains***, and it’s just market forces at work. Talking heads will tell us that gigantic oligopolistic corporations will use those profits to build new factories and increase supplies. Or some other claptrap from Econ 101 textbooks.

Discussion

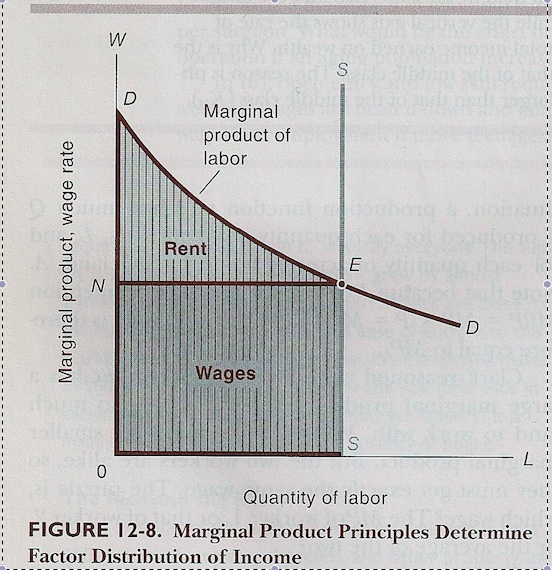

1. The Fed protects capital at the expense of labor. That’s what we mean when we say that inflation is such a big problem we have to hammer working people with unemployment to guard against inflation. It’s true that inflation affects working people, but why is there no way to solve that problem by penalizing capital? After all, inflation due to corporate actions, as in the case of the supply chain, market power, price-gouging and favorable government treatment is just as dangerous as any inflation driven by wages.

2. Reich points out that there isn’t any evidence of wage push inflation. Quite the contrary. Working people have been pounded by Covid and by aggressive union busting, and by price-gouging, and by surging health care costs and student debt. They haven’t caught up. He doesn’t say it, but the top quartile has done quite well, and the higher up in wealth and income people are, the better they’ve done.

3. Corporations have rigged the market structure so that working people are screwed. Government has done little to help. Can you imagine Congress stepping in to help working people? They can’t even raise the minimum wage. How long will people put up with this mistreatment?

=========

* Here’s the methodology. The number is a ratio, with all wages and salaries and proprietor’s labor compensation in the numerator, and what I take to be Gross Domestic Product as the denominator, all measured in constant dollars.

** Here’s the definition.

Profits from current production, referred to as corporate profits with inventory valuation adjustment (IVA) and capital consumption (CCAdj) adjustment in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs), is a measure of the net income of corporations before deducting income taxes that is consistent with the value of goods and services measured in GDP. The IVA and CCAdj are adjustments that convert inventory withdrawals and depreciation of fixed assets reported on a tax-return, historical-cost basis to the current-cost economic measures used in the national income and product accounts. Profits for domestic industries reflect profits for all corporations located within the geographic borders of the United States. The rest-of-the-world (ROW) component of profits is measured as the difference between profits received from ROW and profits paid to ROW.

*** David Dayen, editor of The American Prospect, has produced a terrific series explaining the breakdown of the supply chain. Hint: it isn’t Biden’s fault.