On October 4, 2011 (just before Jeffrey Sterling’s trial was originally due to start) the government submitted a motion that, in part, sought to prevent Sterling from presenting “any evidence or any argument that the CIA has manipulated documents.” The motion presented the crazypants idea that the CIA might alter or destroy documents as part of a conspiracy theory that the CIA wanted to blame Sterling for leaks others had made.

There is absolutely no evidence that the CIA was out to get the defendant, or that the CIA orchestrated some grand conspiracy to blame the defendant for the leaks to Risen. Any arguments or comments that the CIA engages in misconduct or has manipulated documents or evidence in order to blame the defendant for the disclosure of national defense information appearing in Chapter 9 lacks any merit and will needlessly send the Court, the parties, and the jury down an endless Alice-in-Wonderland rabbit hole.

Sterling’s lawyers were nonplussed by this demand. “Documents will be admitted if they are authenticated and otherwise admissible.”

Now, if DOJ were writing about most governmental agencies, you might interpret this request as no more than prosecutorial caution, an effort to exclude any hint of the other things the same motion tried to exclude — things like selective prosecution.

Except the CIA is not most governmental agencies.

Indeed, it is an agency with a long and storied history of serially destroying evidence. The Eastern District of VA US Attorney’s Office knows this, too, because they have so much experience reviewing cases where CIA has destroyed evidence and then deciding they can’t charge anyone for doing so.

And while I don’t expect Judge Leonie Brinkema of CIA’s own judicial district to therefore deny the CIA the presumption of regularity, I confess DOJ’s concern that Sterling might suggest CIA had doctored or destroyed evidence makes me pretty interested in what evidence they might have worried he would claim CIA doctored or destroyed, because with the CIA, I’ve learned, it’s usually a safer bet to assume they have doctored or destroyed evidence.

Especially given the two enormous evidentiary holes in the government’s case:

- The letter to the Iranians Merlin included with his newspaper-wrapped nuclear blueprints

- A report of Merlin’s activities in Vienna

As I lay out below, CIA’s story about the letter to the Iranians is sketchy enough, though the government’s ultimate story about it is at least plausible. But their story about Merlin’s non-existent trip report is sketchier still. I think the evidence suggests the latter, at least, once did exist. But when it became inconvenient — perhaps because it provided proof that Bob S lied in the cables he wrote boasting of Mission Accomplished — it disappeared.

But not before a version of it got saved — or handed over to — James Risen.

If I’m right, one of the underlying tensions in this whole affair is that a document appeared, verbatim, in Risen’s book that proved the CIA (and Bob S personally) was lying about the success of the mission and also lying about how justifiable it would be to have concerns about the operation.

The CIA and DOJ went to great lengths in this trial to claim that the operation was really very careful. But they never even tried to explain why the biggest evidence that it was anything but has disappeared.

Merlin’s letter to the Iranians

I’ve noted before that the FBI admits it never had a copy of the letter the government convicted Sterling of leaking to James Risen. “You don’t have a copy of the letter” that appears in Risen’s book, Edward MacMahon asked Special Agent Ashley Hunt. “Not in that exact form,” she responded.

Nevertheless, Count 2, Count 3, and Count 5 all pertain to a letter that appears in Risen’s book, the letter FBI never found. The letter appears at ¶¶ 58 to 63 of the exhibit version of the chapter in question.

To be sure, FBI did obtain versions of this letter, as cables introduced at trial reflect. The first iteration appears in Exhibit 30 (a cable describing a November 4, 1999 meeting), and discussions of the revisions process appears in Exhibit 33 (a cable describing a December 14, 1999 meeting). Exhibit 35 — dated January 12, 2000 and describing a January 10 meeting between Sterling and Merlin — provides the closest version to what appears in Risen’s book, in what is called (in Exhibit 36) the fifth iteration of the letter. The only difference (besides the signature line, presumably, according to the CIA’s currently official story) is the January 12, 2000 cable, based on a meeting that took place 7 weeks before Merlin left for Vienna, said this:

So I decided to offer this absolutely real and valuable basic information for [Iranian subject 2], about this possible event.

Whereas in Risen’s book that passage appears this way:

So I decided to offer this absolutely real and valuable basic information for free now and you can evaluate that. Also I sent e-mail to inform [the Iranian professor] about this possible event.

Now, it’s fairly clear that neither Sterling nor anyone else handed this January 12, 2000 cable itself, in its entirety, over to Risen. That’s because, in Risen’s book (see ¶21), he described Merlin as having been paid $5,000 a month. Yet ¶7 of the January 12, 2000 cable states clearly that Merlin made $6,000 a month. In fact, according to CIA records released at trial, the only years during which Merlin made $5,000 a month appear to be 2001 (at which point Sterling no longer had access to this compartment; this could have been retroactive to 2000 except it doesn’t reflect what Sterling seems to have understood when he wrote cables on salary issues) and 2005 (when Risen was writing his book, but when Sterling was long gone from the CIA) — though in his deposition, Merlin did say he made $5,000 a month during that period, before later saying it he did so the following year. (Remember Merlin was on medically-prescribed Oxycontin when he gave his deposition, so he may have a good explanation for some of his inconsistent answers.)

Moreover, it’s clear that’s not the final letter.

That’s true, first of all, because CIA did not intend it to be the final letter. In the cable where Sterling provided the verbatim text of the fifth iteration, he “suggest[ed] this letter can be pared down a bit to remove the puffery language included by [Merlin].” In response on January 14, 2000, Bob S wrote (Exhibit 36),

We agree with [Sterling’s] comments that the verbiage needs to be tightened up still further to make sure the Iranians understand what he has and on what terms. He should say explicitly that he is offering the schematic and associated parts list free to prove that he can provide further information, and acknowledge that what he is providing initially is incomplete. There should be a very clear message that he expects to be paid for the rest of the details they will need if they want to build the device.

[snip]

Each iteration of his draft letter is better than the previous one, so [Sterling]’s patience seems to be paying off. It is worth our while to take the extra time to make sure he finally gets it just right, since the letters will have to do much of the work for us with the target.

Now, given Merlin’s payment strike at the following two meetings, it is possible CIA never got around to making the changes Bob S wanted. The fact that Bob S, not Sterling, wrote the cables from those meetings means we would never know, because unlike Sterling, Bob S never included the text of correspondence in cables he wrote (as I laid out here). But Bob S — who ran both the remaining meetings before the Vienna trip with Merlin — clearly wanted changes. And while the letter appearing in Risen’s book retains what Sterling called Merlin’s “puffery” language, it does reflect two of the changes Bob S asked for: reiteration that this package was meant as an assessment package, and an indication Merlin had emailed IS2 to alert him to the package (though see my questions about whether he really did in the update to this post).

In his testimony, Bob S claimed that what appeared in the book was the “nearly final draft,” explaining that the reference to Merlin getting paid was “sharpened” still further after the version that appears in the book. If true, given the way the final meetings worked out, Bob S may have been the only one who would know that.

Assuming CIA was honest with FBI about its records (again, given CIA’s history, not a safe assumption), one of three things could have happened with this letter. First, someone — Sterling or anyone else with access to the Merlin operation cables — could have recreated the letter from the January 10 cable, adding in language that might have served Bob S’ stated goals (though the replacement language definitely sounds like Merlin’s syntax). Alternately, Merlin or his wife could have shared the actual final letter with Risen directly. Or, a revised version of the letter could have been shared with Bob S, and possibly Sterling, and whoever got it could have shared it with Risen, even if it never got officially added to CIA’s archives.

Before I get into how Merlin’s testimony fails to address those possibilities, note one more thing. At least according to Merlin’s testimony, the letter that appears in Risen’s book may not be the one he left in Vienna.

While this passage is unclear (and it is based off of an FBI 302, which are notoriously unreliable in any case and appear to have been so with Agent Ashley Hunt, given other witnesses’ testimony), it seems to suggest that not only did Merlin “sanitize” the letter he brought on a disk to Vienna (as instructed by Bob S on February 21, 2000), but that he left it sanitized when he handed it over to the Iranians.

MacMahon: You actually told the FBI in 2006 that you did not follow instructions from the CIA as to how the bring the note with you to Vienna, did you?

Merlin: Yeah. If it was a question of my security, I didn’t. My life, life of my family, of course I will not.

MacMahon: I understand that, sir, and I appreciate that, but my question is, though, did you not follow the instructions given to you by Bob as to how to draft the note when you got to Vienna?

Merlin: Yeah. If it put in danger my life or, like, my close relatives, of course I would not follow.

[snip]

MacMahon: Sir, do you remember telling the FBI that instead of writing the letter on your computer, you saved it onto a diskette, and that for operational security and your own protection, you left out sensitive terms in the draft saved on the diskette — and I’ll skip those — and substituted generic words? Do you remember telling the FBI that?

Merlin. Yeah. I told it today: Device 1, Device 2, Device 3.

MacMahon: And you never told the CIA handlers that you did this since the action was in violation of their instructions, correct?

Merlin: Nobody asked me.

If that’s what Merlin really did, then it would mean where the letter in Risen’s book describes Merlin handing over a design for a TBA 480, Merlin’s final letter would have read only “Device 1” or similar. But I think it possible that Merlin did as he was told, and de-sanitized the letter, adding back in names of nuclear bomb parts, sitting in the Hotel Intercontinental’s Business Center in Vienna. Though in this case, if Merlin’s testimony is confused we can’t blame the Oxycontin, because the testimony is from 2006.

But the CIA — at least according to questionable sworn testimony given at the trial — doesn’t know for sure one way or another.

It’s only a nuclear blueprint. Who needs to know what the ultimate accompanying letters really said?!?!

Which is where Merlin’s testimony gets interesting. In defense attorney Edward MacMahon’s cross-examination at Merlin’s deposition, he emphasized that Merlin’s response to prosecutor Jim Trump was the first time ever that Merlin had claimed he had destroyed the disk on which the only copy of the final letter was stored (as well as the sanitized version, probably).

MacMahon: The first time you–you were, you were asked questions over, over a space of many years, and you never told the FBI at all that you had destroyed the disk that you took to Vienna, did you?

Merlin: I don’t know, but there was, was no reason to bring it back. It just put myself in additional danger to have such disk in possession. If somebody stop me and read this disk, I’m in trouble.

MacMahon: Okay. But you didn’t tell the FBI, you didn’t tell anybody until today as a matter of fact that that’s what your story was as to what you did with the disk in Vienna, correct?

Merlin: I don’t know, but again, it was no reason to keep this disk when action was, operation was accomplished, and no reason to keep it as a drawing, as letter, as whatever.

Let me interject and note that when the defense asked Bob S (whose court testimony came after Merlin’s deposition) whether Merlin had told him he had destroyed the disk with the letter on it, Bob S responded, “I believe he did.” Remarkably, Bob S didn’t see fit to include that detail (or his inability to verify what they letter said) in the cables he wrote about “Mission Accomplished!”

Perhaps because, by destroying the disk with the letter would have made it impossible for Sterling to have had the final version of the letter (given the record I’ve laid out here and in this post), Merlin explained that he had given the final to Sterling — and only to Sterling — two weeks before he left for Vienna.

MacMahon: So when you came back from Vienna, you didn’t bring a copy of any — any — the letter with you, did you?

Merlin: Of course not. For what?

MacMahon: You just — my only —

Merlin: To get jail time?

MacMahon: I’m, I’m just asking you questions, sir. You didn’t bring it back, right?

Merlin: Yeah.

MacMahon: So you never gave a copy of the final letter to Mr — excuse me, to Bob or to Mr. Sterling, correct?

Merlin: I did before leaving. I cannot go without final version of letter. So Jeff got it.

MacMahon: Okay. When did he get it? What is your testimony as to when he got it?

Merlin: Maybe two weeks before or — I don’t, I don’t remember exact date.

MacMahon: All right. Was Bob present at that meeting?

Merlin: No.

MacMahon: You have a specific recollection sitting here now of, of giving that letter to Mr. Sterling and not Mr. — not Bob sometime 15 years ago, correct?

Merlin: Yeah, I have it.

MacMahon: And it’s a different letter from the one that’s in the book, isn’t it?

Merlin: No. it’s the, it’s the same letter.

MacMahon: It’s the exact same letter?

Merlin: Yeah, or very similar.

MacMahon: That’s all you can say is it’s similar?

Merlin: Yes.

As the defense pointed out in their closing argument, it was not possible for Merlin to have provided only Sterling the final two weeks before his trip. While Merlin did hand Sterling a copy — which appears in the January 10 cable — that was 7 weeks before the trip. And while Merlin did meet with Sterling two weeks before his trip, on February 14, 2000, Bob S attended that meeting and Merlin stormed out before any business got done (at least per the cable written by Bob S). Now it’s certainly possible that Merlin is just misremembering how much before the trip he handed Sterling what was, in fact, pretty close to the letter than appears in Risen’s book, if he handed a final version to anyone before the trip, it more likely would have been to Bob S, not Sterling.

There would, of course, be an easy way to determine what Merlin brought to Vienna: To check the computer on which Merlin drafted it.

Only according to Merlin, FBI never did that — never even asked to do that (and if they had, even in 2003 when they first began the investigation, he thinks he probably had already sold the computer with its nuclear sales correspondence with Iran zeroed out).

MacMahon: Were you ever asked at any time by the FBI to give them a copy — or to give them the computers that you used to draft any of these notes?

Merlin: This computer was too old, and I replace it later.

MacMahon: Okay. When–were you ever asked by the FBI to provide to them any computer hardware that you had in, in 2000 or anytime thereafter?

Merlin: I wasn’t asked.

MacMahon: Never asked.

Merlin: No.

[snip]

MacMahon: Do you recall when it was that you destroyed that computer or got rid of it, whatever you did with it?

Merlin: I believe I format it to hard drive and sell it.

MacMahon: Do you know when that was?

Merlin: 2001 probably.

Now, FBI’s failure to find the letter they claim — and a jury convicted — Sterling of sharing with Jim Risen is actually the less problematic of the two gaping evidentiary holes in the CIA’s story. As I said above, it’s plausible that someone just took the January 10 iteration, filled it in with the changes Bob S had asked for (though those didn’t help the narrative being pitched to Risen, so it’s unclear why that person would do so), and handed it off.

Merlin’s trip report

Why oh why do I keep finding myself writing about the provenance of CIA trip reports?

Perhaps because the stories about who read them and how they got them always end up being the crux of the story?

You see, while I’m perfectly willing to accept that whoever leaked Merlin’s letter to James Risen did so based off the January 10, 2000 cable, I find the CIA’s currently operative story that Merlin did not give CIA a trip report from his trip to Vienna, and/or the CIA did not capture all the details of what Merlin told them in his March 9, 2000 debriefing meeting, to be laughable.

Bob S at least intended to order Merlin to bring back a trip report. His February 17, 2000 cable (Exhibit 37) promised he’d stress that requirement in his next meeting with Merlin, if he deemed the Russian scientist ready to carry out the mission. “C/O will stress that we need a full and detailed report of his visit and reception,” Bob S wrote. Though, because Bob S preferred flourish in his cables rather than details that might get him in trouble later, we don’t know whether he did stress that.

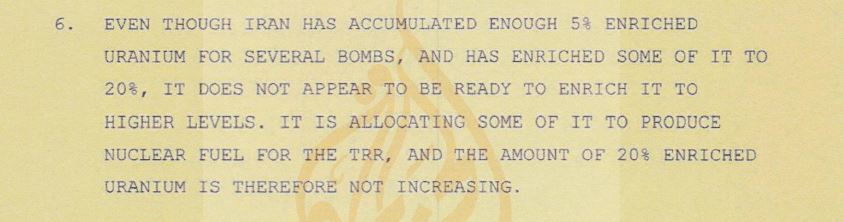

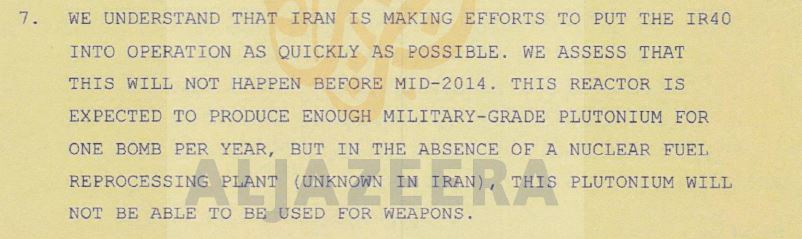

And Risen’s book not only indicates that Merlin did write a report, but it quotes from that report.

At 1:30 P.M. I got a chance to be inside of the gate, at the entrance of the Iranian mission, the Russian later explained in writing to the CIA. “They have two mailboxes: one after gate on left side for post mail (I could not open it without key) and other one nearby an internal door to the mission. Last one has easy access to insert mail and also it was locked. I passed internal door and reached the mission entry door and put a package inside their mailbox on left side of their door. I cover it old newspaper but if somebody wants that is possible to remove from mailbox. I had no choice.”

There are other details in Risen’s book — notably, other exact times for when Merlin was at the building — that would logically appear in a report and perfectly match Merlin’s current story (and those aspects of Merlin’s story are remarkably crisp 15 years later).

Mind you, Risen’s book also seems to quote from a CIA debriefing of Merlin, complete with its author’s (according to Merlin) incorrect supposition of why Merlin didn’t ask for directions in Vienna.

“I spent a lot of time to ask people as I could [language problem] and they told me that no streets with this name are around,” the Russian later explained to the CIA, in his imperfect English.

As Merlin explained it in his deposition testimony, his German was good enough to ask directions of Viennese passers-by, but — Merlin claimed in his deposition to explain why he hadn’t asked directions — he didn’t want to ask questions about Iran’s IAEA mission. But whether it was an accurate characterization or not, that parenthetical comment — “language problem” — sure seems to be a direct quotation from an actual document.

Now, before I talk about what explanations Bob S and Merlin offered about this, let me just present what the government appears to have claimed at the trial (not having charged Sterling with leaking this document they never found, unlike the letter they never found, the government didn’t make a really credible effort to explain it at all). They effectively suggested that Merlin explained all these details — down to the exact times he arrived at the Iranian mission, as well as the detail about the newspaper-wrapped nuclear blueprint that never showed up in any cable — in a debriefing both Sterling and Bob attended. And then Sterling remembered those exact details from 2000 until 2003 (or 2004) when he leaked them to Risen. Indeed, the government pointed to Sterling’s presence at that debriefing of which they claim no record was ever made as proof that he is one of the only people who could have leaked details like the times and that Merlin wrapped his nuclear blueprints in newspaper.

No. I don’t find that explanation credible either.

Bob S must have had conflicting motives with regards to Merlin’s report in his trip, because if a report existed, then it would offer further proof than the cables he wrote already do that he lied blatantly by suppressing how big of a clusterfuck the operation was. But he clearly wanted Sterling convicted. He offered one hint that might serve both motives.

Bob S claimed that Sterling spoke to Merlin before he arrived for the March 9 meeting. “Sterling told me he had heard something and the news was good; I don’t know what had happened, but I do recall that things had gone well.” When asked on cross why Sterling hadn’t documented that in a cable, Bob S explained that it didn’t need to be documented “because they had a meeting later that day.” Had an extensive conversation between Sterling and Merlin actually occurred, it would have presented an opportunity for Sterling to document the events outside the gaze of Bob S.

Merlin offered up a different story for how Sterling might have recorded details from the debriefing that don’t appear in the cables Bob S wrote: that Sterling recorded the conversation (though this was close to the end of the deposition, and I think this may have been partly fatigue, partly Oxycontin, and only partly an attempt to make his story implicate Sterling).

MacMahon: Okay. When you just talked about what happened in Vienna, you told the FBI that Mr. Sterling didn’t take any notes, right?

Merlin: I cannot recall such details.

MacMahon: Okay. But you don’t recall Mr. Sterling taping your conversation, right? There wasn’t a tape deck sitting there, was there?

Merlin: I don’t know. He always came with a big bag.

MacMahon: So he — you never saw, you never saw Mr. Sterling with a tape deck recording any of your conversations, right?

Merlin: I believe so I, I did see him.

MacMahon: You think you did?

Merlin: I did see him–

MacMahon: You did see him do —

Merlin: –with recorder.

MacMahon: Where was the recorder?

Merlin: I didn’t see it; I told you.

Again, I think Merlin’s attempt to claim that Sterling had recorded this conversation stems from a variety of issues. But the prosecution tried to get the court to alter the transcript to have Merlin claim he didn’t see Sterling tape him. The court reviewed the transcript and deemed this version correct.

All that said, Merlin was a lot squishier about whether he wrote a report than Bob S was (see this post for how Merlin’s verbal dodges match up with known facts in the case).

Mac: How many meetings did you have with Bob when you came back from Vienna in which you discussed what transpired in Vienna?

Merlin: Maybe just one.

Mac: Just one.

Merlin: Um-hum.

Mac: And how many meetings did you have with Jeff when he came — when you came back from Vienna in which you discussed what transpired in Vienna?

Merlin: I don’t remember.

Mac: You didn’t write a written report for them as to what happened, correct?

Merlin: It seems —

Mac: Do you remember?

Merlin: Are you waiting for me?

MacMahon: Yes, sir. I’m sorry, if you answered, I missed it. Did you provide a written report for the CIA as to what happened when you were in Vienna?

Merlin: I cannot recall.

MacMahon: And you recall telling the FBI that when — at your meeting with Mr. Sterling after you got back, that he took very few notes?

Merlin: Who took notes?

Now to be fair, this, too, could be Merlin’s fatigue and pain-killers. Still, given how Merlin’s other memory lapses coordinate with answers that in fact were true, this testimony suggests that Merlin may actually have written a report after all. (And note, MacMahon got Merlin to confirm that it was his 2006 FBI interview — the one in which Merlin’s story seems to have changed in remarkably parallel ways to how Bob S’ story did — where he first explained he had not written a trip report.)

Which brings us to the big problem with Merlin’s claim not to have written a trip report.

His pictures.

As even shows up in Bob S’ first Mission Accomplished cable (Exhibit 44), Merlin “on his own initiative, [] took a series of photographs of the [Iranian mission] building, entrance way, mission door, and the locked mailbox, and presented these to C/O’s.”

Merlin, who claims he didn’t bring a copy of the final letter back to the US with him because he worried if he was caught he’d go to prison, nevertheless brought back photos from the Iranian IAEA mission. Merlin, who claims he didn’t write a trip report after he returned safely to the US, nevertheless took photos as proof that he had done what CIA ordered him to do.

It’s rather unlikely that Merlin would have — on his own accord — taken and brought back these pictures, but not done a trip report for the CIA.

And with that in mind, consider what Merlin says happened to those pictures: either Sterling or Bob S handed them back to Merlin and asked him to destroy them.

Merlin: Yeah, I brought a photo to show.

[snip]

Merlin: I believe they returned the photo to me.

MacMahon: Excuse me?

Merlin: They returned this photo to me.

MacMahon: So the photos was returned to you?

Merlin: Um-hum.

MacMahon: Do you remember telling the FBI that you actually destroyed all those pictures because they weren’t needed?

Merlin: I couldn’t find it.

MacMahon: Do you remember telling the FBI that you destroyed those photos because they weren’t needed?

Merlin: Maybe, but I couldn’t find it actually.

MacMahon: And do you remember telling the FBI that you gave the photographs to Bob or Jeffrey?

Merlin: It was both of them. They — both of them can confirm they saw it.

MacMahon: And it’s your testimony that, that one of them gave you the pictures back and you destroyed them?

Merlin: Yeah, most likely. I don’t — I didn’t get it.

“Yeah, most likely. I don’t — I didn’t get it.”

Now, Bob S, in his testimony, seems to have suggested that those photographs weren’t destroyed, but were instead left in the NY office. Merlin, however, says he was told by his case officer(s) to destroy the evidence he brought back from his trip (which would, probably, show how insecurely Merlin had left the blueprints that CIA had spent $1.5 million having the national lab make, wrapped in their newspaper and sticking out of a locked mail slot). But Merlin said he couldn’t find the photos to destroy when he tried to.

If Merlin’s photos logically suggest that he also wrote a trip report for the CIA, I would suggest it may have met a similarly confused state, particularly if the existence of it — with details about the times he showed up to the Iranian mission but didn’t knock on the door, descriptions of what he really did with the letter to Iran, and details on actions he took that would have implicated the CIA in his operation — became inconvenient for cheerleaders about the operation.

And neither Sterling nor Bob S would have an incentive to admit it once existed. For Sterling, it would provide yet more evidence he had access to the information leaked to James Risen. For Bob S, it would prove he lied about the operation (and, possibly after he learned a leak investigation had started, had evidence destroyed).

In a just world, the government would have spent its time investigating what appears to be destruction of evidence — yet more obstruction of justice by the CIA — rather than prosecuting a 12 year old leak. But this is EDVA we’re talking about. And ignoring curiously missing evidence is all in a day’s work for them.