In advance of today’s hearing (at 10AM ET) on Jim Comey’s vindictive prosecution claim, I want to lay out two aspects of the Comey prosecution that likely doom it, and may doom the larger fever dream of a grand conspiracy case.

Both arise out of the way that Lindsey Halligan was prepped not by prosecutors, but by FBI agents working on the “Director’s Task Force” we know to be led by Jack Eckenrode, the guy who chased Russian disinformation for years based off Kash Patel’s misleading packaging of classified documents back in 2020.

This post will argue that likely all of them, possibly up to and including Kash himself, have tainted themselves by snooping in Jim Comey’s privileged communications. A follow-up will lay out the increasing evidence that Jim Comey’s grand jury presentment is a crime scene.

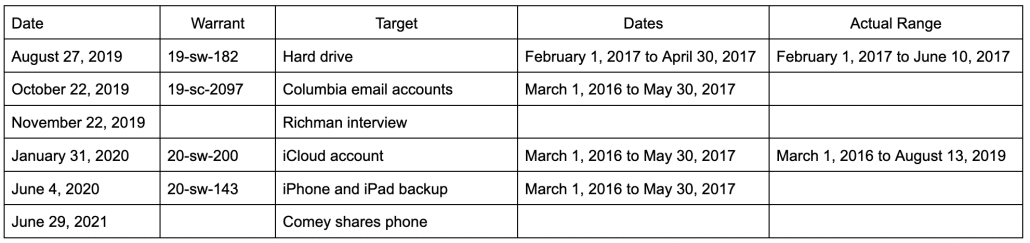

On September 12, FBI agents working on the Director’s Task Force were prepping for EDVA’s September 16 interview with Dan Richman, then led by Erik Siebert. They were searching the full Cellebrite extraction from Richman’s phone, and stumbled on communications Richman conducted using a pseudonym. They didn’t use those communications for the Richman interview, almost certainly because that interview would have been focused on actual suspected crimes rather than the fever dreams of conspiracists. But after that interview led prosecutors to conclude there was no crime that could be charged, Trump removed Siebert, leading Pam Bondi to appoint overt partisan Maggie Cleary, on September 20 (Cleary becomes important for the follow-up). But that wasn’t good enough. Then Trump publicly demanded Bondi install Lindsey Halligan, which Bondi did on September 22. That week, Cleary reportedly heeded prosecutors’ view the case could not — should not — be charged.

But Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer instead prepped with FBI agents working on the Director’s Task Force. Importantly, because DOJ wouldn’t provide Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer with outside help, those FBI agents prepped Lindsey, who knew nothing about how to prosecute a case, themselves.

DOJ headquarters declined to provide lawyers to assist Halligan, and FBI agents and lawyers working to prepare her were denied their request for a para-legal professional to assist in the presentation, according to two people familiar with the matter.

[snip]

Last Tuesday [September 23], Halligan began a crash course to prepare. Justice officials told her that the deputy attorney general’s office didn’t have lawyers to help her, and that it was against federal rules of criminal procedure for one of the attorneys from Justice headquarters to be in the grand jury room, one source familiar with the discussions said.

There’s a natural tension between FBI agents and prosecutors. The former get really invested in their targets, leading them to believe their case is stronger than it is. The latter, traditionally, have focused on how to sustain DOJ’s prior near-perfect record of convictions, all while keeping their bar licenses, and so they focus on what will be admissible and credible at trial, not their emotional belief they’ve caught a baddy.

Just as one example of how this pressure works, Jack Eckenrode — the head of this effort! — may well be the guy who tried to force Patrick Fitzgerald to indict Karl Rove two decades ago by telling journalists Rove was going to be indicted. Someone wanted Rove indicted (so did I!), but Fitz presumably believed that Robert Luskin had nudged Rove through serial admissions successfully enough to avoid perjuring himself too badly, and also that Rove would be useful at Scooter Libby’s trial, which he was.

But with the FBI agents prepping Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer, that moderating influence of a prosecutor didn’t exist. It was Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer, being led by the nose by hyper-partisan FBI guys performing for their hyper-partisan boss hunting the baddy that Kash had targeted even before getting the job.

And that’s important, because when Special Agent Spenser Warren describes “team” in this affidavit about the breach of Jim Comey’s privileged texts, it likely includes Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer.

On the morning of September 25, 2025, the team was preparing for an indictment of James Comey, to occur later that afternoon. SA Warren provided case agent SA Miles Starr and an FBI Office of General Counsel (OGC) attorney a limited overview of the text message communications to and from “Michael Garcia” (now understood to be Daniel Richman). SA Warren advised SA Starr and the FBI OGC attorney that some of the messages appeared to reference potential future legal representation. The FBI OGC attorney immediately advised that any of the text message communications referencing potential future legal representation should not be part of the indictment preparation. SA Warren provided the indictment preparation team a two-page document containing limited text message content only from May 11, 2017, predating the reference to potential future legal representation.

Take a step back though. This conversation should never have happened! That’s because the imagined crime these FBI agents were presenting was that Comey had lied when he told Ted Cruz he had never told anyone at FBI to act as an anonymous source. These texts post-dated Richman’s departure from the FBI by over three months. Even if they hadn’t accessed these texts illegally, they don’t help you prove your case (unless you neglect to tell grand jurors and judges when Richman left FBI, as this prosecution team persists in doing).

But because there was no grown-up in the room, they accessed the texts.

There are three pieces of evidence that the entire group — Miles Starr, Eckenrode, but also Lindsey Halligan, and with her, her Loaner AUSAs — all were tainted by the privileged communications, and along with it the grand jury.

First, Warren described that he shielded Starr from the taint of the privileged comms by isolating two pages of texts, “only from May 11, 2017, predating the reference to potential future legal representation.” But Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer likely presented eight pages of those texts, marked as Government Exhibit 10, on the fourth page of which Richman says, “just got goahead,” like he had just spoken to Comey, and the fifth through eighth pages of which post-date May 11 entirely. Someone went back into evidence they had been told included privileged texts and got an extra six pages of evidence.

And if Lindsey was already presenting texts well beyond the time that Comey retained Richman, that makes it more likely that when Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer told the grand jury there was better evidence they would get for trial, she was thinking of the other side of Richman’s communications, the communications between Comey and Richman.

But if that’s what she was thinking, the only way she would say that would be if she knew of the privileged comms — the comms an FBI lawyer specifically advised not to include in grand jury prep. That doesn’t mean she looked at them. It means she knew they were there and intended to go get them. When Miles Starr or whoever went back to get 8 pages of texts, he likely searched only the ones that included Mike Schmidt, thereby avoiding seeing any communications between Comey and Richman, but he did so because he knew those privileged communications were there.

Classic taint.

Also note, in the transcript, this comment appeared just one page after the other misinstruction on the law that (per Judge William Fitzpatrick) Lindsey gave, suggesting that Comey would have to take the stand. I’m sure the FBI agents who prepped her have the fever dream that they’ll see Comey on the stand, but no prosecutor would even silently imagine she could get a well-lawyered defendant to take the stand, much less blurt it out in front of a grand jury.

The other piece of evidence that Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer was tainted by that privileged communication is the way that, even before sharing any of this discovery with Comey, she and the Loaner AUSAs set out to breach Comey’s privilege. They filed a motion to do so as one of their first filings (perhaps not coincidentally on the day Maggie Cleary was fired). And then, a week later, when they tried to rush Michael Nachmanoff into granting that motion, they invented a new theory of crime to get access to these communications: that Jim Comey lawyered up with Dan Richman and Pat Fitzgerald (and David Kelley) on May 11, 2017 in order to leak classified memos showing Donald Trump’s corruption.

Additionally, based on publicly disclosed information, the defendant used current lead defense counsel to improperly disclose classified information.

[snip]

This fact raises a question of conflict and disqualification for current lead defense counsel. Some of the communications in the potentially protected material are from the same time as the focus of the DOJ OIG report. Before litigating any issue of conflict or disqualification, the parties should have access to all relevant and non-privileged information. The sooner that the potentially protected information is reviewed and filtered, the sooner the parties can make any appropriate filings with the Court.

The imagined crime here is a leak of classified information, not a lie in response to a question from Ted Cruz, and so irrelevant to this prosecution.

In real time, Comey dismissed this claim as the bullshit fever dream it was: Comey was an Original Classification Authority and didn’t believe anything in his memos was classified, and the specific memo shared with Mike Schmidt had no classified information in it by any measure.

But consider how abusive the claim looks now. To get these texts, FBI agents working on the Director’s Task Force had gone back into material seized from Richman obtained more than five years earlier, they did so without a fresh warrant specific to either this prosecution or the fever dreams the FBI agents are really pursuing, rather than accessing the stuff that excluded the stuff Richman had said was privileged, they accessed the raw data and ostensibly did so for communications that could not have been responsive to their intended purpose (that is, to find out what, if anything, Richman shared anonymously while still at the FBI). And their interim claim they invoked to breach privilege, that this was a conspiracy to leak classified information, had nothing to do with this case, or even the larger fever dream conspiracy — the one they’re pursuing in Florida — that this was a conspiracy to be mean to Donald Trump.

A classic fishing expedition.

Betcha some money the Loaner AUSAs are delaying here so someone can try to get a warrant in Florida invoking a crime-fraud exception based on the well-known crime of being mean to Donald Trump.

Indeed, in Loaner AUSA Gabriel Diaz’ emergency motion for a delay (authored, as so many of these abusive filings are, by James Hayes), he doesn’t even argue this is about taint. He’s arguing (in a sentence fragment) only about whether Miles Starr read the actual texts in question, not whether he went back and searched for their counterpart texts to put together an 8-page exhibit for Lindsey to use.

Indeed, the government believes the Magistrate Judge may have misinterpreted some facts he found when issuing the latest order to release the grand jury materials to the defendant. For instance, whether the defendant has any standing to challenge the Richman materials, the full context of the statements made by the prosecutor to the grand jury, that Agent-3 was exposed to potentially privileged material, and that two indictments were presented to the grand jury.

Much of what the prosecutors have done since that day is a frantic bid to get those privileged texts, texts that could in no way serve to help prove this case as charged.

It’s sunny (and very cold by Irish standards), so I’m going to go take a walk before I map out the team — like James Hayes and OGC lawyer Gabriel Cohen — that’s lurking behind the foolish Loaner AUSAs fronting for all of this. But there’s a very good chance all of them are driven by taint, the taint of a fishing expedition into Jim Comey’s privileged communications.

This prosecution appears to have become more focused on finding some way out of that taint than on actually winning this particular prosecution against Kash Patel’s nemesis.

Cast of characters

Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer

Tyler Lemons: On loan from EDNC

Gabriel Diaz: On loan from EDNC

James Hayes: Litigation Attorney at Main Justice, he is listed as author of the following:

Gabriel Cohen: Metadata lists him as OGC, possibly in Detroit, he is the author of:

Henry Whitaker: The former Solicitor General of Florida and currently Pam Bondi’s counselor, he is the signed author of:

Kathleen Stoughton: An AUSA in South Carolina with solid appellate experience, she is listed as author of:

Michael Shedd: A newish AUSA in South Carolin, he is listed as author of:

lheim: Metadata lists as author of: