WikiLeaks boosters have embraced a really bizarre new entry in the propaganda case to support Julian Assange this weekend: An article by two Icelandic journalists that purports to prove that, “The veracity of the information contained [in the June 2020 superseding indictment against Julian Assange] is now directly contradicted by the main witness, whose testimony it is based on.” This is an article about Sigurdur Ingi Thordarson, AKA Siggi, the sociopath that Assange chose to hang out with for a period in 2010 to 2011, who does have a role but by no means the “main” role in the case against Assange. The journalists who wrote the article present as credible Siggi’s claim, from someone that everyone agrees is a pathological liar, that he’s telling the truth now, rather than when he testified to US authorities in 2019.

The journalists who wrote the article and all the WikiLeaks boosters who have embraced it are arguing that the article somehow proves that an avowed liar is telling the truth now about lying in the past. Even as WikiLeaks boosters are pointing to the Icelandic legal judgment that Siggi is a sociopath, they are once again welcoming him into the WikiLeaks fold because the avowed liar claims to have lied.

This is what Assange’s boosters are now staking his defense on: convincing you to accept the words of liars as truth.

Except, Siggi retracts nothing substantive that is alleged in the indictment, so this drama is instead a demand that you accept the word of a liar rather than read the documents to show that the liar’s claims are irrelevant to the charges against Assange.

The article proves it doesn’t understand US law

Before I get into how little of what the article presents even relates to the indictment, let me show how badly the authors misunderstand (or misrepresent) US law. The last eight paragraphs of the article insinuate that, because US prosecutors gave Siggi immunity for testimony in 2019, he exploited that immunity to commit new crimes in Iceland. The suggestion starts by claiming that the outdated NYT Problem remained true in 2017 and parroting the WikiLeaks claim that therefore what must have changed was the appointment of Bill Barr (who was confirmed after the initial complaint and first indictment had already been obtained).

Although the Department of Justice had spent extreme resources attempting to build a case against Julian Assange during the Obama presidency, they had decided against indicting Assange. The main concern was what was called “The New York Times Problem”, namely that there was such a difficulty in distinguishing between WikiLeaks publications and NYT publications of the same material that going after one party would pose grave First Amendment concerns.

President Donald Trump’s appointed Attorney general William Barr did not share these concerns, and neither did his Trump-appointed deputy Kellen S. Dwyer. Barr, who faced severe criticism for politicizing the DoJ on behalf of the president, got the ball rolling on the Assange case once again. Their argument was that if they could prove he was a criminal rather than a journalist the charges would stick, and that was where Thordarson’s testimony would be key.

I don’t fault journalists in Iceland from repeating this bit of propaganda. After all, even Pulitzer prize winning NYT journalists do. But the NYT problem was overcome when WikiLeaks did something in 2013 — help Edward Snowden get asylum in Russia — that the journalists involved at the time said was not journalism. What’s novel about this take, however, is the claim that career prosecutor Kellen Dwyer was “Trump-appointed.” Dwyer has been an EDVA prosecutor through four Administrations, since the George W Bush administration.

I assume that the reason why it’s important for this tale to claim that Dwyer was appointed by Barr is to claim the immunity agreement under which Siggi — and several other known witnesses to this prosecution — testified did something it didn’t.

In May 2019 Thordarson was offered an immunity deal, signed by Dwyer, that granted him immunity from prosecution based on any information on wrong doing they had on him. The deal, seen in writing by Stundin, also guarantees that the DoJ would not share any such information to other prosecutorial or law enforcement agencies. That would include Icelandic ones, meaning that the Americans will not share information on crimes he might have committed threatening Icelandic security interests – and the Americans apparently had plenty of those but had over the years failed to share them with their Icelandic counterparts.

All the agreement does is immunize the witness against prosecution for the crimes they admit during interviews with prosecutors they were part of, so as to avoid any Fifth Amendment problem with self-incrimination. This is not about hiding Siggi’s role in WikiLeaks; it has been public for a decade. Moreover the article even described the US sharing just the kind of security threat information this paragraph claims they did not.

Jónasson recalls that when the FBI first contacted Icelandic authorities on June 20th 2011 it was to warn Iceland of an imminent and grave threat of intrusion against government computers. A few days later FBI agents flew to Iceland and offered formally to assist in thwarting this grave danger. The offer was accepted and on July 4th a formal rogatory letter was sent to Iceland to seal the mutual assistance.

All that immunity did was provide DOJ a way to ask Siggi about his role at the time. It didn’t immunize future crime in Iceland, nor did it give him any incentive to claim Assange asked him to hack things he hadn’t.

That’s the extent to which these journalists are spinning wildly: getting the facts about the prosecutors and the law wrong in a piece claiming to assess how Siggi recanting what they assume he told prosecutors in 2019 would affect the indictment.

Siggi’s purportedly retracted claims in several cases don’t conflict with the indictment

And, even beyond claiming Siggi is the “main witness” against Assange, they seem to misunderstand the indictment, in which Siggi’s actions play a role in a limited set of overt acts in a Computer Fraud and Abuse Act charge. Because there are so many ways that Assange allegedly engaged in a long-ranging effort to encourage hackers, jurors could find Assange guilty even if none of the Siggi events were deemed credible, and he is central (though his testimony may not be) to just a portion of the overt acts in the CFAA charge.

In fact, this piece never once cites the indictment directly.

Instead, they cite Judge Vanessa Baraitser’s ruling on Assange’s extradition. They cite fragments though, not the single paragraph about Siggi’s role in the CFAA charge that is relevant (indeed, was key) to her decision:

100. At the same time as these communications, it is alleged, he was encouraging others to hack into computers to obtain information. This activity does not form part of the “Manning” allegations but it took place at exactly the same time and supports the case that Mr. Assange was engaged in a wider scheme, to work with computer hackers and whistle blowers to obtain information for Wikileaks. Ms. Manning was aware of his work with these hacking groups as Mr. Assange messaged her several times about it. For example, it is alleged that, on 5 March 2010 Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning that he had received stolen banking documents from a source (Teenager); on 10 March 2010, Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning that he had given an “intel source” a “list of things we wanted” and the source had provided four months of recordings of all phones in the Parliament of the government of NATO country-1; and, on 17 March 2010, Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning that he used the unauthorised access given to him by a source, to access a government website of NATO country-1 used to track police vehicles. His agreement with Ms. Manning, to decipher the alphanumeric code she gave him, took place on 8 March 2010, in the midst of his efforts to obtain, and to recruit others to obtain, information through computer hacking. [italics and bold mine]

Baraitser includes the overt acts involving Siggi — that Siggi gave Assange “stolen banking documents,” may have been his source for “a list of things he wanted” including recordings from Parliament, and provided Assange access to an Icelandic police website — not for Siggi’s role in the action, but for Assange’s representations to Chelsea Manning about them. “Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning … Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning … Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning” certain things about Siggi, and what mattered most is that Assange made the claims, not whether what Assange claimed to Manning was true or not, because it was part of getting her to leak more documents.

The two times Stundin does cite Baraitser’s judgment, they cite it misleadingly, particularly with regards any claims made about the indictment. The sole citation to the critical paragraph of Baraitser’s ruling I cited above appears this way:

More deceptive language emerges in the aforementioned judgment where it states: “…he [Assange] used the unauthorized access given to him by a source, to access a government website of NATO country-1 used to track police vehicles.”

This depiction leaves out an important element, one that Thordarson clarifies in his interview with Stundin. The login information was in fact his own and not obtained through any nefarious means. In fact, he now admits he had been given this access as a matter of routine due to his work as a first responder while volunteering for a search and rescue team. He also says Assange never asked for any such access.

As noted above in bold, in the critical paragraph pertaining to Siggi of the ruling, this topic matters solely for how it related to Assange’s interactions with Manning. And where she introduces the allegation earlier in her ruling, Baraitser makes no claim that Siggi’s access was unauthorized, only that Assange’s was.

It is alleged that Mr. Assange kept Ms. Manning informed about these hacking activities: on 5 March 2010, he told her that he had received stolen bank documents from a source (Teenager); on 10 March 2010, he told her that, in response to a “list of things we wanted”, a source had provided him with four months of recordings from phones located within the Parliament of a “NATO country 1”; on 17 March 2010, he told her that he had used the access, given to him by a source, to obtain unauthorised access a government website used to track police vehicles, in “NATO country 1”. [italics and bold mine]

No one is claiming that Siggi obtained the access via nefarious means. Rather, Baraitser claims only that Assange’s — who was not an Icelandic first responder — was unauthorized, to which Siggi’s purported retraction is irrelevant.

And the indictment provides further context — context that addresses another of Stundin’s claims.

41. In early 2010, a source provided ASSANGE with credentials to gain unauthorized access into a website that was used by the government of NATO Country-1 to track the location of police and first responder vehicles, and agreed that ASSANGE should use those credentials to gain unauthorized access to the website.

42. On March 17, 2010, ASSANGE told MANNING that ASSANGE used the unauthorized access to the website of the government of NATO Country-1 for tracking police vehicles (provided to ASSANGE by a source) to determine that NATO Country-1 police were monitoring ASSANGE.

43. On March 29, 2010, WikiLeaks posted to its website classified State Department materials regarding officials in the government of NATO Country-1, which Manning had downloaded on February 14, 2010.

Again, what is key here is that the credentials were unauthorized for Assange (which they were), that Assange went on to tell Manning about it, and that those things happened when Manning was leaking documents pertaining to Iceland as well. Nothing in Siggi’s supposed recantation is even relevant to that.

Similarly, Stundin complains that Baraitser referred to a file from an Icelandic bank as “stolen,” when Siggi says that he understood the file to have been leaked by whistleblowers, not stolen.

One is a reference to Icelandic bank documents. The Magistrate court judgement reads: “It is alleged that Mr. Assange and Teenager failed a joint attempt to decrypt a file stolen from a “NATO country 1” bank”.

Thordarson admits to Stundin that this actually refers to a well publicised event in which an encrypted file was leaked from an Icelandic bank and assumed to contain information about defaulted loans provided by the Icelandic Landsbanki. The bank went under in the fall of 2008, along with almost all other financial institutions in Iceland, and plunged the country into a severe economic crisis. The file was at this time, in summer of 2010, shared by many online who attempted to decrypt it for the public interest purpose of revealing what precipitated the financial crisis. Nothing supports the claim that this file was even “stolen” per se, as it was assumed to have been distributed by whistleblowers from inside the failed bank.

As noted above, in the key paragraph in Baraitser’s judgment, she described that, “Mr. Assange was engaged in a wider scheme, to work with computer hackers and whistle blowers to obtain information for Wikileaks.” The inclusion of whistleblowers here makes it clear that she understood some of this to be leaked rather than hacked.

Moreover, in the indictment, the claim is about how Siggi’s actions tie to requests Assange made of Manning and (presumably) David House (both of whom were also given immunity to testify, though Manning refused to do so), both of whom took steps to access Icelandic files.

35. In early 2010, around the same time that ASSANGE was working with Manning to obtain classified information, ASSANGE met a 17-year old in NATO Country-1 (“Teenager”), who provided ASSANGE with data stolen from a bank.

[snip]

39. On March 5, 2010, ASSANGE told MANNING about having received stolen banking documents from a source who, in fact, was Teenager.

[snip]

44. On July 21, 2010, after ASSANGE and Teenager failed in their joint attempt to decrypt a file stolen from a NATO Country-1 bank, Teenager asked a U.S. person to try to do so. In 2011 and 2012, that individual, who had been an acquaintance of Manning since early 2010, became a paid employee of WikiLeaks, and reported to ASSANGE and Teenager.

The indictment doesn’t source the claim that the file was stolen to Siggi (certainly, the FBI has other ways of finding out what happens to financial files, and in many contexts, a whistleblower leaking them would amount to theft). Nor does it say Siggi stole it. Nor does Siggi’s understanding of whether it was leaked or stolen matter to the conspiracy indictment at hand, not least given its import to Assange and Manning’s alleged attempts to hack a password so she could leak documents, just what Siggi claims he believed bank employees had done. What matters, instead, is the joint shared goal of accessing it. Nothing Siggi says in his supposed recantation of this story undermines that claim.

Stundin’s third specific denial — that Siggi didn’t himself hack the phone recordings of MPs, but instead received them from a third party — is the single denial of a specific claim made in the indictment.

Thordarson now admits to Stundin that Assange never asked him to hack or access phone recordings of MPs. His new claim is that he had in fact received some files from a third party who claimed to have recorded MPs and had offered to share them with Assange without having any idea what they actually contained. He claims he never checked the contents of the files or even if they contained audio recordings as his third party source suggested. He further admits the claim, that Assange had instructed or asked him to access computers in order to find any such recordings, is false.

The indictment does claim that Siggi obtained these files after Assange requested that Siggi hack things.

In early 2010, ASSANGE asked Teenager to commit computer intrusions and steal additional information, including audio recordings of phone conversations between high-ranking officials of the government of NATO Country-1, including members of the Parliament of NATO Country-1.

[snip]

On March 10, 2010, after ASSANGE told Manning that ASSANGE had given an “intel source” a “list of things we wanted” and the source had agreed to provide and did provide four months of recordings of all phones in the Parliament of the government of a NATO Country-1, ASSANGE stated, “So that’s what I think the future is like ;),” referring to how he expected WikiLeaks to operate.

Siggi denies he hacked anything to get these files, but he does say he got them. He got them, instead, from a third party, unasked. Even if that’s true (and even if the third party wasn’t the intel source), the key point here is that Assange enticed Manning to keep providing requested documents by claiming he had successfully requested and obtained the recorded calls.

The specific denials in this story, even if true, don’t actually deny anything of substance and in one case is completely consistent with the indictment. More importantly, none of these denials are relevant to the way in which Baraitser used them, which is to discuss how Assange’s interactions with Siggi, Manning, and House were part of a unified effort; that unified effort is the only reason Iceland (but not Siggi alone) is key.

The story is silent about or confirms the more serious allegations about Siggi

And the parts of the indictment where Siggi’s role is key, which pertain to Assange’s alleged entry into a conspiracy with Lulzsec to hack Stratfor and to hack a Wikileaks dissident, are unaddressed in this story. For example, Stundin describes reading chat logs Siggi provided — which is not the full set of chatlogs available to the US government, though Stundin claims they must be comprehensive — and finding no proof in the chatlogs that anyone at Wikieaks ordered him to ask other hackers to hack websites. But their focus is on why Siggi asked other hackers to hack Icelandic sites. There’s no mention of hacking US sites.

The chat logs were gathered by Thordarson himself and give a comprehensive picture of his communications whilst he was volunteering for Wikileaks in 2010 and 11. It entails his talks with WikiLeaks staff as well as unauthorized communications with members of international hacking groups that he got into contact with via his role as a moderator on an open IRC WikiLeaks forum, which is a form of live online chat. There is no indication WikiLeaks staff had any knowledge of Thordarson’s contacts with aforementioned hacking groups, indeed the logs show his clear deception.

The communications there show a pattern where Thordarson is constantly inflating his position within WikiLeaks, describing himself as chief of staff, head of communications, No 2 in the organization or responsible for recruits. In these communications Thordarson frequently asks the hackers to either access material from Icelandic entities or attack Icelandic websites with so-called DDoS attacks. These are designed to disable sites and make them inaccessible but not cause permanent damage to content.

Stundin cannot find any evidence that Thordarson was ever instructed to make those requests by anyone inside WikiLeaks. Thordarson himself is not even claiming that, although he explains this as something Assange was aware of or that he had interpreted it so that this was expected of him. How this supposed non-verbal communication took place he cannot explain. [my emphasis]

More bizarre still, Stundin describes Siggi admitting that “Assange was aware of or that he had interpreted it so that this was expected of him.” This actually confirms the most important key allegation pertaining to Lulzsec, that when Siggi was negotiating all this, he claimed to DOJ and still claims now, Assange knew and approved of it. And in fact the indictment alleges that Siggi proved to Topiary he was working with Assange by filming himself sitting with Assange, a non-verbal communication that — because Siggi deleted it — would not have been included in the chatlogs that Stundin insists had to be comprehensive.

To show Topiary that Teenager spoke for WikiLeaks so that an agreement could be reached between WikiLeaks and LulzSec, Teenager posted to YouTube (and then quickly deleted) a video of his computer screen that showed the conversation that he was then having with Topiary. The video turned from Topiary’s computer screen and showed ASSANGE sitting nearby.

In fact, the only specific denial regarding LulzSec in this piece pertains to Sabu, not any of the people that Siggi is alleged to have spoken with.

Thordarson continued to step up his illicit activities in the summer of 2011 when he established communication with “Sabu”, the online moniker of Hector Xavier Monsegur, a hacker and a member of the rather infamous LulzSec hacker group. In that effort all indications are that Thordarson was acting alone without any authorization, let alone urging, from anyone inside WikiLeaks.

There’s no allegation in the indictment pertaining to Siggi’s conversations with Sabu. It alleges he was part of the conspiracy, but not that he spoke with Siggi.

Finally, the one other key allegation involving Siggi in the indictment — that Assange asked him to hack a WikiLeaks dissident — is actually sourced independently to an Assange comment. Nothing in this article denies it specifically, but it’s not even necessarily sourced to Siggi.

There’s no there there in this article. Moreover, all the claims in it — most notably, that Siggi is a sociopath and a liar — have been long known. What the article misunderstands is where Siggi’s testimony may be important, where it served to explain existing documentary files, and the many ways in which DOJ ensured it didn’t rely on such an easily discredited witness. The article also doesn’t understand how co-conspirator statements — statements that have already been made — get entered at trial.

You go to trial with the sociopaths that a target like Julian Assange has chosen to associate with, not with the Boy Scouts you’d like to have as witnesses. But this indictment relies on that sociopath far less than Stundin would have you believe, and Siggi’s purported retractions do very little to rebut the indictment or Baraitser’s ruling about the case. More importantly, the article claims that the DOJ’s purported reliance on a sociopath is fatal, but their argument is based on the claims of that same sociopath.

WikiLeaks boosters claim it exonerates Julian Assange that someone they claim is a liar claims he lied

Admittedly, this is what WikiLeaks always does with their shoddy propaganda claims. They did it with their misrepresentations about a pardon dangle delivered by suspected Russian asset Dana Rohrabacher, they did it with the admission that former Sputnik employee Cassandra Fairbanks personally ferried non-public information about Assange’s prosecution from Don Jr’s best friend to Assange, and they did it with unsupported allegations about UC Global.

They don’t care what the actual evidence is or supports, so long as they have a shiny object that their army of boosters can point to to claim the indictment says something other than it does.

But this one is particularly remarkable because of shit like this.

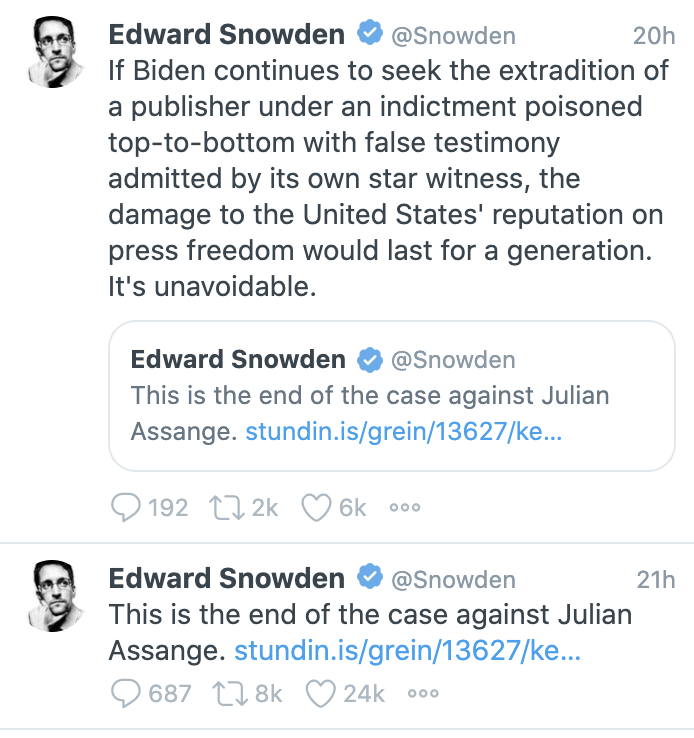

Edward Snowden, who explained his theft of vast swaths of secret documents based on a claim that he had the judgment to know what he was seeing was abuse, claims to believe that this article “is the end of the case against Julian Assange.” That is, Ed Snowden has displayed for all the world that his critical reasoning skills are so poor that he doesn’t understand that — even if every single thing Siggi is reported to say in this article were true (including his claim that Assange knew and approved of his efforts to forge ties with LulzSec) — it would do little damage to the indictment against Julian Assange.

It amounts to Ed Snowden putting up a sign saying, “Oh sure, I knew better than the entire NSA, but I have such poor critical thinking skills I can’t read through a misleading headline.”

Worse still, what Ed Snowden is telling you to do is to trust the word of someone that — everyone agrees! — is a lying sociopath!! Ed and the entire WikiLeaks booster community here are endorsing the truth claims of someone they acknowledge in the same breath is a liar and a sociopath. What matters for them is not any critical assessment of whether Siggi could be telling the truth, but that the liar is saying what will help them.

Finally, the craziest thing is that Edward Snowden, who not only is personally named in five of the fifty CFAA overt acts, but whose own book confirms key allegations in those five overt acts, pretends that someone else is the star witness. Snowden’s own book, itself, could result in a guilty verdict on the CFAA claim, and the only way to prevent his book from serving that role is for Ed Snowden to claim he himself is a liar. This indictment could only be “poisoned top-to-bottom with false testimony” if Snowden came out tomorrow and claimed he was lying in his own book.

Ed Snowden’s own claim to be telling the truth distinguishes him as a whistleblower rather than a spy. But here, he affirmatively asks you to believe someone everyone agrees is a liar. And based on the belief that that liar was this time telling the truth, Ed asserts that an indictment that implicates his own truth claims is “poisoned top-to-bottom with false testimony.”

Update: One more thing I didn’t stress enough. This story doesn’t claim that prosecutors lied to the UK. Rather, they claim (without evidence about the full set of witnesses and evidence that DOJ relied on), that Siggi misled DOJ about two claims that don’t affect most of the CFAA charge.

Update: I’ve added language making it clear that the claim that Assange knew Siggi was negotiating ties with Lulzsec is still apparently based on what Siggi told DOJ and what he maintains now. That overt act is not the only one showing Assange entering into an agreement before they hacked Stratfor though.

Update: Subtropolis has convinced me to drop the references to Siggi as a child rapist, as he was underage too at the time.

Update: Corrected that the W administration was four Administrations ago.