Existentialism and Ethics

Index to posts in this series. Please read this first; at least the section on de Beauvoir’s definition of ambiguity.

I’m on the road, and reading The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir. She was an Existentialist, as one would expect from a person in a long-term relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre. In Chapter 1 she gives an explanation of parts of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, the leading book on Existentialism. She distinguishes it from Stoicism and Marxism, but I won’t address that.

I think she opens with this because any systematic approach to ethics should begin with a statement of the writer’s understanding of human nature. De Beauvoir defines a specific ambiguity which I discussed in the introduction to this series. Her views are also informed by another ambiguity, the absurd. We want certainty. We want a foundation. But there isn’t one. We have to proceed, we have to live, without that certainty we want.

I read Being and Nothingness in College, but I didn’t, and don’t, care much for it. I agree with the Existentialists, including Sartre, that the universe is indifferent to its parts, from planets to mountains, flowers, insects, animals and human beings. I think there is no meaning to existence apart from our experience of it. Sartre explains that this lack of meaning gives us humans a radical degree of freedom, which we cannot avoid. Sartre’s explanation seemed to me to be wrapped up in silly little epigrams, like “Man’s being is not to be.” They did and do annoy me no end.

De Beauvoir gives a more sympathetic reading to Sartre’s tome, and for anyone interested, her explication in Chapter 1 of the wordy and needlessly obscure Sartre is worth reading. The point is to ground her discussion of ethics as a part of the human response to the meaninglessness of life and the freedom and responsibility it entails.

De Beauvoir discusses parts of Sartre’s book

Sartre’s statement that man is the being whose being is not to be begins with the notion of being. That seems to mean a fixed being, as an animal or a tree. People do not necessarily have a fixed nature. We might act like we do, we might aspire to have such a fixed being. But by nature, people live in a present filled with possibility, and want to participate in that possibility. We want to live in that wild freedom.

Freedom gives us the space in which we exist. We interact with others seeking to know them and in the process to know ourselves. We pursue our personal projects. We experience the savors and ugliness and all that come with existence. We want to be like gods in our existence, but this is an impossible and stupid goal.

I can not appropriate the snow field where I slide. It remains foreign, forbidden, but I take delight in this very effort toward an impossible possession. I experience it as a triumph, not as a defeat. This means that man, in his vain attempt to be God, makes himself exist as man, and if he is satisfied with this existence, he coincides exactly with himself. P 12-3.

By appropriate, I think she means merge myself, take possession of in my being, as a god would do. I think the idea of “coinciding” here means that we become fully human, our full selves, all we can be or aspire to be. We can and should aspire to be fully human, but we cannot be gods.

De Beauvoir says that for Sartre, one implication of embracing this freedom is that a fully human person will not accept any outside justification for their actions. People want to justify themselves, and we have to choose standards for justification we learn from others or create ourselves. Our ethics, then, come from the collective or from ourselves. We cannot have standards that emanate from some non-human place. I think this means that we must reject the absolute authority claimed by some religions.

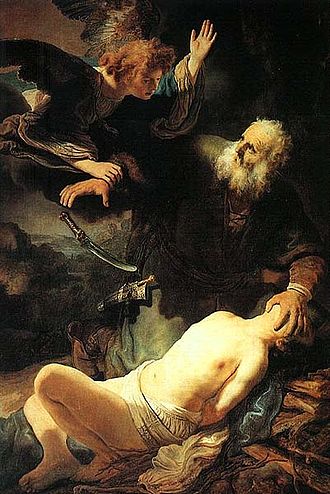

The second implication is that we bear responsibility for the results of our actions. We can’t claim that some external being is responsible for bad consequences. We act, we bear responsibility for the consequences. I think Fear and Trembling by the early Existentialist Sören Kierkegaard gives us a good example in the story of Abraham and Isaac. Abraham believes that the Almighty wants a human sacrifice, namely his only son Isaac. He acts on that belief. Whether he was right or wrong, he bears the consequences: a lost precious child, or a child tortured by the awareness that his father would kill him.

De Beauvoir says that we cannot escape our freedom, and we cannot avoid our responsibility. But we can simply refuse to will ourselves to exercise that freedom, out of “laziness, heedlessness, capriciousness, cowardice, [or] impatience” P. 25.

De Beauvoir says that responsibility only exists in our minds, in contemplation of the consequences of our actions. Feeling that responsibility happens over time, as those consequences become clear. This is a recognition that only grown-ups have these concerns.

The fact that we do not accept a justification outside ourselves is not a bar to an ethics.

An ethics of ambiguity will be one which will refuse to deny a priori that separate existants can, at the same time, be bound to each other, that their individual freedoms can forge laws valid for all. P. 18.

I think this is the source of ethics for de Beauvoir. We cooperate with other people to decide for ourselves what constitutes a justification for actions and projects. We choose to work together because we are part of the collective and our actions affects the collective directly. We share some of the burden of responsibility with others.

Discussion

1. I hope it’s clear which parts of this are mine and which are de Beauvoir’s. But it seems less important with this book. This book asks us to participate in the process of creating ethics, and therefore to think about the foundation of her ethics.

I think this book is useful because de Beauvoir is writing after horrors of the Third Reich and to a lesser extent those of Stalin were known and seen up close. That leads me to think her ethics addresses people of her day. Perhaps she intended to interrogate the behavior of the German people who enthusiastically welcomed and followed the Nazis. Certainly that’s an issue Camus addressed directly in The Plague.

Whether or not this was her purpose, we should ask ourselves what this foundation means for our understanding of the MAGAts, the people who enthusiastically follow Trump and his enablers and the filthy rich bastards who put him back in power.

2. I think we are formed by the collective in a deep way. For more, see my posts on The Evolution of Agency by Michael Tomasello, and other posts. It seems to me that this is the major contribution de Beauvoir makes to Existentialism. She describes Being and Nothingness as focused on the individual, who thrusts himself into the world. The foundation of her book is the ambiguity of being both an individual and being part of the collective.

I think we are formed by the people around us, parents, siblings, other relatives, friends, and institutions. I was raised Catholic, first in a traditional environment and then in a liberal environment. That has a profound influence on my sense of ethics,

I think we have to face our history directly and exercise our freedom to question what we were taught. We have to see ourselves clearly apart from the group in order to assess what we truly believe based on our own experience. Only then are we able to contribute something of our own to the ethics project.

3. I hate this translation: collective has an ugly Stalinist connotation.

4. De Beauvoir writes “… the ends toward which my transcendence thrusts itself …” on p. 14. The word thrust is used three times in Chapter 1, each time apparently quoting Sartre. In each case the connotation seems aggressively phallic. We don’t thrust ourselves into anything. I used the words “find” and “inject” above, trying to suggest that we will to act, but not in any aggressive sense.

I haven’t read The Second Sex, and I wonder if contemplation of this aspect of Being and Nothingness coupled with her sense of the importance of society had an influence on her thinking after writing this book.

“People do not necessarily have a fixed nature.”

I cannot agree with that, not broadly speaking. Though we are, in the details of our behavior, extraordinarily complex, it seems certain that we are a social animal. All of our strengths and weaknesses, including our compulsion to find some “meaning to life” which is irrefutable and exists somehow outside of our individual selves, would appear to arise out of our being, fundamentally, members of a group. We can’t stand to be alone. We are so compelled to find society that we will conjure it up in our minds, out of fear and desire, and call it a god.

We will swear our god exists. We will swear that, though we cannot see or hear it in any ordinary way, it speaks to us and guides us. We will use it to bind us together in communities — because we are social animals, fundamentally, and must confront that fact, practically speaking, in our day-to-day lives. Because we are so damn complex, we will make just about anything into a god, and spin it up into a system as complex as we need it to be. It may be a god in a supernatural form, as in the monotheistic or polytheistic religions, or in a more secular form, as in various philosophical and political ideologies, which are never so far removed in their basic forms and dynamics from their religious cousins.

And the meaning that we find is the meaning that we make. That is part of our nature. We must have meaning to our lives. We must find some way to believe in that meaning, be it in a benign way or a harsh way. And we must share it with and among others who we can believe are, in some fundamental way, like us. We are a social animal. We cannot escape that.

‘We are a social animal. We cannot escape that.’

I think it happens: psycho/sociopaths. Some people do ‘escape’. I put that in quotes because that’s an emotionally (and, I guess, politically) loaded word these days. Are we ‘socialised’ or are we ‘indoctrinated’? ‘Education’ or ‘brainwashing’?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychopathy

I often find that music says much more effectively what I’m trying to say:

‘Are you human, or a dud?

Are you human, or d’you make it up?’

Goldfrapp’s Human

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gliD9lRZcs&ab_channel=Goldfrapp

Certainly there are people who insist on the meaning of some religion or other. But tht doesn’t describes all of us. As we will see in Chapter 2 de Beauvoir describes many different ways people cope with freedom and the absurd.

I am frequently asked “for what purpose do mosquitoes serve” in which I explain that there really is no “purpose” to any organism, other than as a human construct in an effort to understand it. I ask them to think about it more like a job were there’s an opening for some labor or resource to be exploited, the most obvious being food and water but also oviposition sites and pollination/seed dispersal.

Most crucially it often allows the species to perpetuate, and is literally called a niche. For mosquitoes, it’s the high protein source in blood they cannot get elsewhere to produce their 200+ eggs but also the extreme environmental conditions as immatures they can withstand. Places fish cannot survive, another key to their survival. The practical effect of evolution is to maximize efficiency (which is why the RWNJ’s love themselves some so-called “social Darwinism”) but the prize isn’t profit for stockholders, it’s surviving to perpetuate the species.

Then I turn their question on its head and ask them if they think acting as a host for countless disease organisms serves a suitable purpose, a sort of “viral airlines”.

I am

To choose and lose and not to cower,

Every single day to wake up and see

Those wrinkled eyes my face in a mirror

How much different are we than a tree?

Which does not ask much just water and air

To breathe, and sun to shine, and soil to root

Our complicated tale is not so clear

But like a tree, grow strong and bend and fruit.

Pollination is not a lonely dance,

Reproduction is not our only aim

A grove and a forest are my shelter

Tall red oak, many rings and leaves I claim.

Ed, You say you were “raised Catholic,” from which I draw the (perhaps unfair) inference that you are now “lapsed” or no longer practicing. I was raised by an imperialistically atheist father and a mom who described herself as “agnostic” as long as he stayed with her. Once he ditched her for a younger and non-English-speaking second wife, my mother immersed herself deeply in world religions, toward no specific end but in a way that did inform her art. (She was a painter.)

My grandparents started out Baptist and Lutheran and wound up vaguely (on one side) and profoundly (on the other) Episcopalian. I really started reading the Bible in high school, because of Faulkner, and fell in love with Jesus’s teachings–in part because they supplied an agreed-upon–by most in this country–set of moral principles that resonated with teenage me and which I could invoke with others.

Nowadays I witness “Christians” violating precept after precept of the only moral authority they themselves will allow to govern us. I have never set my own sights on any Afterlife, preferring to live by my own principles–which I can express in Gospel terms if necessary to persuade–here in this life, where it might do my fellow beings some good. I can only interpret these so-called Christians, like Mike Johnson, as bartering their present lives on the promise of one after death. The deaths of others seem meaningless to them in this grand bargain.

“You CANNOT petition the Lord with prayer!” Jim Morrison said it more concisely. RIP Jim.

Amos has words about petitioning: https://www.patheos.com/blogs/slacktivist/2025/09/04/first-things-first-biblical-priorities/

“Christians.., like Mike Johnson bartering their present lives on the promise of one after death.”

In reality, aren’t they less likely to acquire eternal life by violating the precepts espoused by its gatekeepers, such as bearing false witness?

That’s why I called Johnson and his ilk “so-called Christians.” They pick and choose which precepts they follow, make rules for everyone else, and fail to register the hypocrisy, at least in public.

Visit often, rarely post. Picture a five year-old boy gathered in the basement of a Catholic schoolhouse for kindergarten orientation by two Benedictine Brothers. Northwestern Minnesota. His father (two of his sisters were Benedictine nuns) had been reactivated and whisked away to fight commies in Korea. The pair of Brothers taking turns telling the most outrageous lies about what God does to bad little boys and girls that half the incoming “class” was in tears.

Flash forward to 1968 and find that boy whisked away to fight commies in South Viet Nam and witness bad things happening to good people and good things happening to bad. That little boy from Minnesota, age 80, is now certain the only “afterlife” rewarded is parked in the memories of family and acquaintances.

[Welcome back to emptywheel. Please use the SAME USERNAME and email address each time you comment so that community members get to know you. You attempted to publish this comment as “tbob” which does not comply with the site’s naming standard; it has been edited to reflect the username to which you changed in 2023. Please check your browser’s cache and autofill; future comments may not publish if username does not match. /~Rayne]

Thankyou.

More profound than I expected …

A lot of deep questions as befits a post on Philosphy. I grea tly appreciate these posts, thanks. Freedom is another word for nothin left to lose, as a commercial Nashville songwriter once wrote. This fits Sarte’s usage pretty well. Someone with nothing to lose is capable of anything for any or no reason, which doesn’t leave much to build on. And a “collective” is a step away from that, but as that existentialist Tonto once asked, what do you mean “we”, white man? How you define a collective is how you fence in or game the discussion. As a non-philosopher I know enough to know these are trivial points to philosophers, but they set the stage, I believe.

Throughout the book de Beauvoir uses the term “man”, which at the time she was writing was taken to mean men and women, or people. I think she refers to the collective as the entire human race, all of us, men and women and children. I don’t think philosophy works if it only applies to a subset of the human race.

First, I have concerns about de Beauvoir’s work in translation. For example, the title of the text is Pour une morale de l’ambiguïté, which translates directly into English as For a morality of ambiguity. Perhaps this doesn’t seem important to some, but morals are not the same as ethics; I wonder how much discourse about this particular work would change with a focus on morality alone avoiding ethics until discussion of morality is exhausted, then moving toward the construction of ethics.

What else in this same text may have been misunderstood because of translation? There’s also a middleman, the translator Bernard Frechtman, who did both this work and some of Sartre’s. Was he inserting anything he interpreted from Sartre, or his own interpretations? Your observation about repeated usage of the word “thrust” is a possible artifact of the invisible editorial effect; what does the original text in French use?

Secondly, I don’t think this de Beauvoir text can be read on its own without also reading it against The Second Sex. De Beauvoir discusses the ways in which women have been subjugated by men in her text and yet she is supposed to be invested in Existentialism’s absolute freedom? There’s hypocrisy here, but her partner Sartre also had his own hypocrisies, ex. his support of Israel as it colonized Palestine, his reliance on his white cis-het male privilege.

Reading The Second Sex also requires consciousness of translation’s potential for damaging meaning. The original translation to English was badly done, bordering on outright maliciousness. If de Beauvoir could rely on Existentialism’s absolute freedom, she wouldn’t have been shat on so badly by a white male translator working on her most important text.

Lastly, I have to tell you your first graf made me laugh so hard last night when I opened this to do some copyediting. I was still laughing when unexpected quests showed up, kept me amused all evening.

It’s the second sentence in particular that did me in. De Beauvoir has the absolute freedom to choose if she subscribes to Sartre’s philosophy and this is what she chose:

A slop-shouldered soft-handed guy who smokes like a chimney? Call me shallow but this guy…oof. Apparently his epigrams did it for her.

I’ll hold off my thoughts about the premise of freedom based on aimlessness and meaninglessness of the universe for the moment. That’s a separate comment.

I hope that I am not taking this too far off-topic from the post—thank you Ed.

From Rayne: “Perhaps this doesn’t seem important to some, but morals are not the same as ethics …”

I get confused between “morals” and “ethics”, but I think that one way to look at this, which helps me, is from the perspective of (often overlapping) duties owed to others: moral, civic, ethical, fiduciary.

Moral duties adhere to every human toward all others and manifest as human rights—and by extension some duty towards animals and the planet. For example, there are the rules of warfare and regulations of the EPA.

Civic duties adhere between those in a particular society; e.g., a duty that allows others the right to vote, to travel.

Ethical duties adhere to those in a profession (physicians, lawyers, etc.) towards others in the profession to uphold the principles of that profession. Lawyers and judges have a duty to hold other lawyers, judges, (and those who enforce the law), accountable for ethical lapses. But, for example, how do lower courts make upper-level courts accountable for their ethical lapses?

Fiduciary duties adhere to those in a profession—whose experience and training make them uniquely able to recognize harm and mitigate risk—to those not similarly situated. These duties are based on trust. Did Joni Ernst, uniquely situated as a veteran and a female, fail in her fiduciary duty to protect us from Pete Hegseth? Similarly, did Drs. Cassidy, Marshall, Paul, and Barrasso, uniquely situated as physicians, fail to protect us from RFK, Jr.?

“Moral duties” are not the same as morals. Capisce? Until we nail down an understanding about the nature of morals and what univeral morals are, we can’t build “moral duties” nor ethics.

Ethical duties arise from ethics. Fiduciary duties arise from law, which one might hope arise from ethics. Come on, surely you’ve noticed how a GOP majority in Congress can change fiduciary duties we are to expect.

I can’t even trust Frechman to get the title of this book right? Ican’t find another translation, and I don’t read French.

In the text Frechtman seems to use the terms ethics and morality or morals interchangeably. I think there is a difference, and it matters. Notions of morality are informed directly by our emotions, our feeling, and our judgment. Ethics points to systematization and to rules. Our sense of morals may or may not align with ethical principles in any specific case. As we will see in Chapter 2, de Beauvoir is very judgmental. She knows some things are better than others, and she says so.

As to Sartre, well, some years ago now I read a book about the relationship between Sartre and Camus. Two things stuck out for me. First, Sartre was a snob about his excellent education.and disrespected Camus’ lack of that education. Camus was by far the better writer, and the more normal person. Second, Camus despised Stalin, and broke with the communist party years before Sartre did.

If you’re still in Paris you stand a better chance of finding a cheap copy of the original text in French. There are a few copies for sale in Alibris, just search for Pour une morale de l’ambiguïté and you’ll find a couple good quality copies under $20.

I have to wonder even about the use of the word “man” — did she write “man,” which in the 1940-50s was commonly used to refer to the collective humankind as was the word “mankind,” or did the translator use that? If de Beauvoir used it, it’s yet another example of her hypocrisy. She may have been unconscious at times about it, but then she wrote The Second Sex. How could she not be conscious of the occupation of language by one gender?

Re: Sartre et Camus — I don’t think Sartre had much else to be snobby about but his education. I wonder if he projects his insecurities at times.

I don’t have this work in the original. It may be that the frequent invocation of “man” reflects the mid-twentieth century habit of translating the French pronoun “on” (which does not have a gender) not as “one” but as the then-more-accepted “man,” the universality of which did not come into general question until well after deBeauvoir’s time.

Nor was exegetical linguistics *truly* her lingua franca. At least as I read her work, she seems more interested in language as a medium for the expression of ideas than as a subject itself. This is, however, a broad generalization.

Rayne, that photo really stunned me! You could superimpose the face of Bonnie Parker over deBeauvoir’s without retouching a thing.

While she might have been “aware” of patriarchy as a controlling force, what was the actual lexicon to draw upon available, such as the word and meaning of “occupied by” in the 1940s when she wrote Ambiguité? My understanding is that it was Fanon in the early 1950s that really pushed forward the lexical concept of being “occupied” or “colonized” by oppressive social rules and habits. That is not to say that Beauvoir and contemporaries in the late 1940s weren’t part of the movement towards this change in language to describe the concept of being occupied or colonized by concepts that were foreign to one’s own sense of what is and is not possible in the mores of a particular social setting, etc. I guess what I’m trying to get at is that one should not expect the specificity of a new lexicon to reside in works that pre-date the neologic progression required to enunciate clearer one’s own states of feeling or self-perceived being.

The e-book version of “Ethics and Ambiguity” is on sale right now!