Recent improvements in hardware, a massive increase in the number of processors available, and new math tools have increased concerns that computers may soon replace millions of workers. The shorthand for this is Artificial Intelligence, although the term seems like hyperbole considering the kinds of things computers can do at present. The Obama White House issued a paper on this issue, Artificial Intelligence, Automation and the Economy, which can be found here. It cites two studies of the impact of AI on automation over then next 10 years or so. One, by the OECD, estimates about 9% of US jobs may be lost to automation. The other is a more interesting 2013 paper by two professors at Oxford, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, estimating that as many as 49% of US jobs could be lost or seriously affected over 10 or so years.

The Frey-Osborne Paper is here. Frey is a professor in a public policy college, and Osborne is in the engineering college; they aren’t economists. Perhaps for that reason, the introductory sections are instructive on the history of technological change and some of its effects on society. The technical approach of the Frey-Osborne Paper is to identify the bottlenecks that make it difficult to automate the tasks needed in a specific job. They use machine learning to identify patterns in the skills needed by specific jobs.

The authors identify three main bottlenecks to automation:

1. Tasks requiring perception and manipulation. P. 24

2. Tasks requiring creative intelligence. P. 25

3. Tasks requiring social intelligence. P. 26

The O-NET database of jobs is managed by the US Department of Labor. The current version contains detailed descriptions of job tasks for 903 occupations. Here are the top eight tasks of 21 listed for forest firefighter, one of the bright future jobs according to O-NET,:

Rescue fire victims, and administer emergency medical aid.

Establish water supplies, connect hoses, and direct water onto fires.

Patrol burned areas after fires to locate and eliminate hot spots that may restart fires.

Inform and educate the public about fire prevention.

Participate in physical training to maintain high levels of physical fitness.

Orient self in relation to fire, using compass and map, and collect supplies and equipment dropped by parachute.

Fell trees, cut and clear brush, and dig trenches to create firelines, using axes, chainsaws or shovels.

Maintain knowledge of current firefighting practices by participating in drills and by attending seminars, conventions, and conferences.

Frey and Osborne describe their methodology as follows:

First, together with a group of [machine learning] researchers, we subjectively hand-labelled 70 occupations, assigning 1 if automatable, and 0 if not. For our subjective assessments, we draw upon a workshop held at the Oxford University Engineering Sciences Department, examining the automatability of a wide range of tasks. Our label assignments were based on eyeballing the O-NET tasks and job description of each occupation.

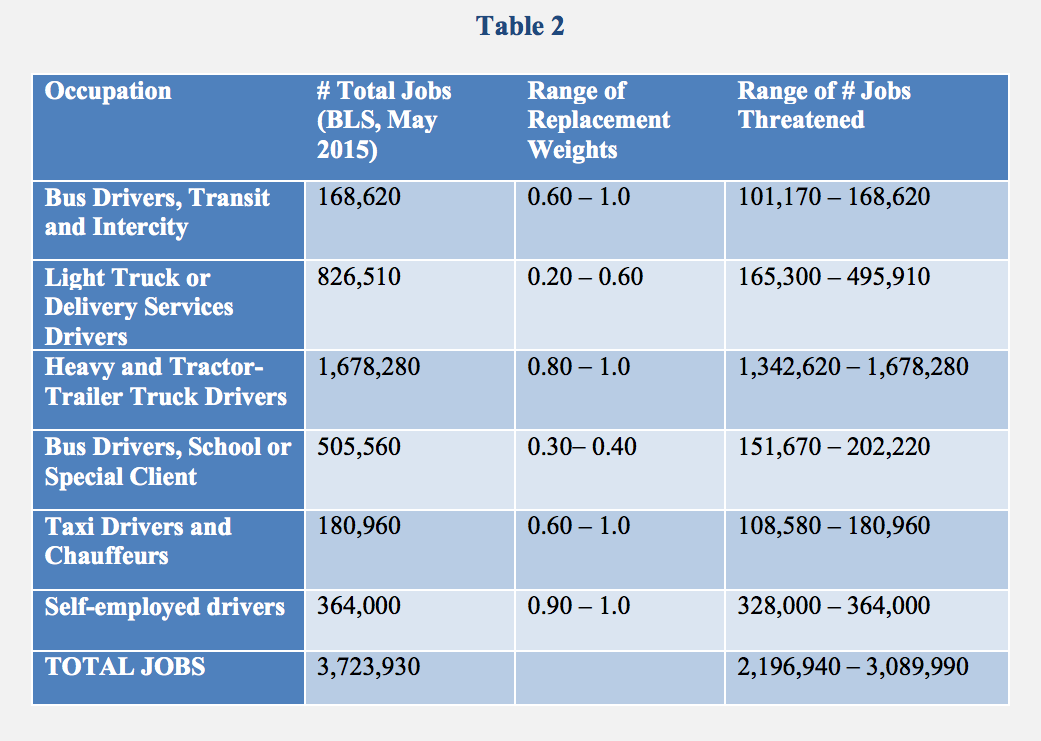

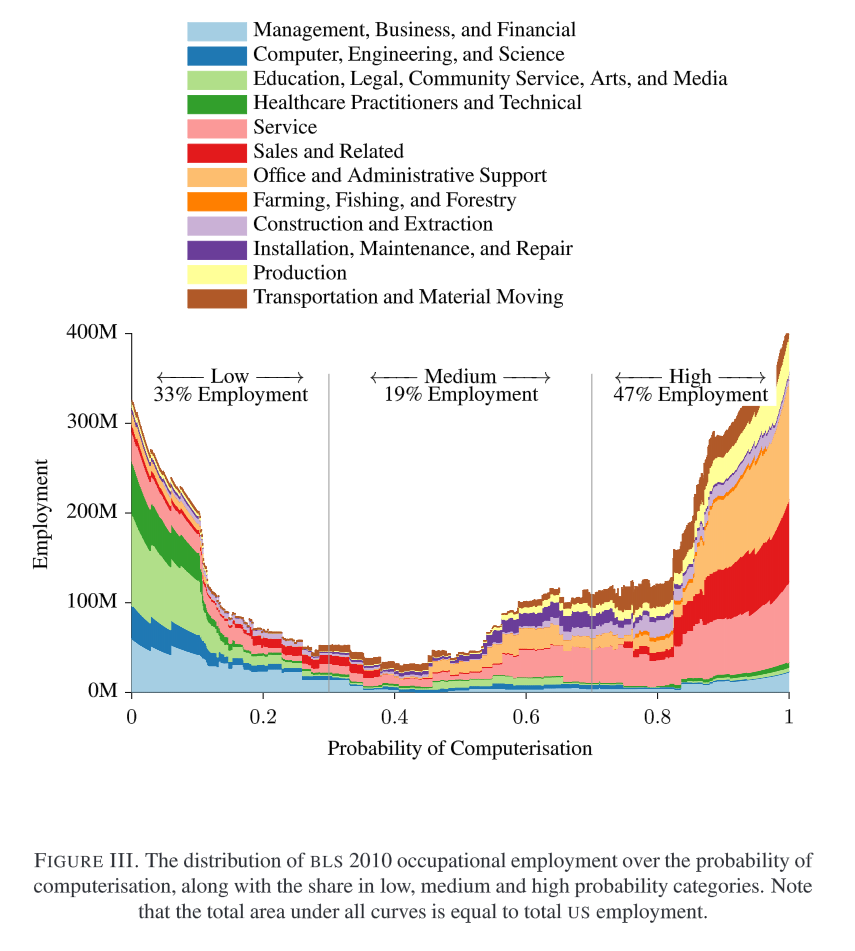

They identified nine variables related to the three bottlenecks and assigned levels of difficulty of the variables in carrying out each task, high, medium, or low. Then they verified their data, and used it as training data in a machine learning program. The paper gives a description of the way they prepared and ran the rest of the O-NET data through the trained machine to estimate the likelihood that each job would be automated over the next 10 years or so. They produced a chart showing the likely effects of AI on categories of jobs. The following chart shows the results of their work.

The authors say that large numbers of transportation and logistics workers, office workers and administrative support workers are at risk. They also think many service workers are at risk as robots become more efficient. They think people whose jobs require great manual dexterity and perception, or high levels of creativity, or strong social intelligence are reasonably safe in the near term. They assert that low-skill workers will have to move to jobs in the service sector that require these skills, and will have to sharpen their own through training and education.

There have been several articles on this issue lately. This one by Reuters says that investors think the future is in automation. Since the election shares in companies working in that area are up dramatically as is an ETF in the sector. Reuters says that this means that investors think that Trump’s assertion he will increase jobs in the manufacturing sector will not happen. Instead, as the cost of advanced technology drops labor becomes expendable. Any increase in manufacturing will have little effect on overall unemployment, as displaced workers move to other jobs with the same employers doing “value-added” tasks.

Matthew Yglesias goes a step farther in this 2015 post at Vox. He says the big problem in job growth in the US is the lack of increase in productivity due to inadequate automation. He thinks rising productivity is essential to higher wages, or more likely a reduction in the time spent working. Yglesias lays out the case for not worrying. He ignores, as all economists do, the possibility that the returns from work might be shared more equitably between capital and labor. His relentless optimism contrasts with the lived experience of millions of Americans, the real lives that gave us Trumpism.

I wonder what Yglesias makes of this article in the Guardian discussing the efforts of the billionaire Ray Dalio to create software to manage the day-to-day operations of the world’s largest hedge fund in accordance with “… a set of principles laid out by Dalio about the company vision.” The article provides a more pessimistic view of the future even for management work.

I don’t have an opinion about these forecasts or the reasoning behind them. Yglesias says people will work less, but doesn’t explain how workers who have no bargaining power will be able to increase their income enough to have free time. Dalio must think that he is so wise that his AI automaton will replicate his success forever, and that his competitors won’t take advantage of the rigidity of his principles.

Suppose that the investors described by Reuters are right, that manufacturing increases but without increased employment in the sector. What will all those Trump voters do next? Change their minds about what they want from the economy and the government that fosters it, and live happily ever after?

I think both Yglesias and Dalio are so steeped in neoliberal economics with its model of human beings as Homo Economicus that they assume these changes will come about smoothly. Nothing else will change; there are no dynamic tipping points. No large number of human beings will raise hell. There will be no feedback effects. The displaced of all ages will just retrain to some other job and/or resign themselves to their reduced lives. They won’t resist, or riot, or insist on government protection, or demand a completely new system. Investment bankers will blandly accept the judgment of computers as to their value and will not insist on being treated like superstars even if the machine says they are just gas giants.

Yglesias and Dalio are wrong. That is precisely what history says won’t happen.