I had a dream last night that the documents side of the Jack Smith report, which is the subject of a heated legal battle right now, revealed that Smith developed evidence that Trump had given documents he took to the Saudis in the context of several major business deals. To be clear: It was a dream! I don’t think that’s the most likely content of the report.

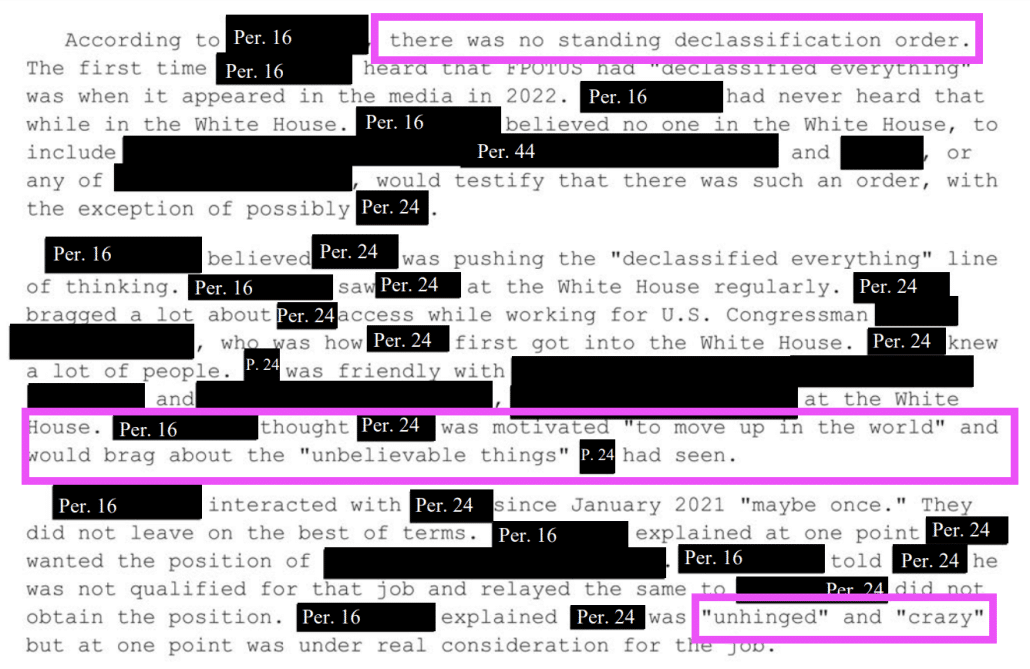

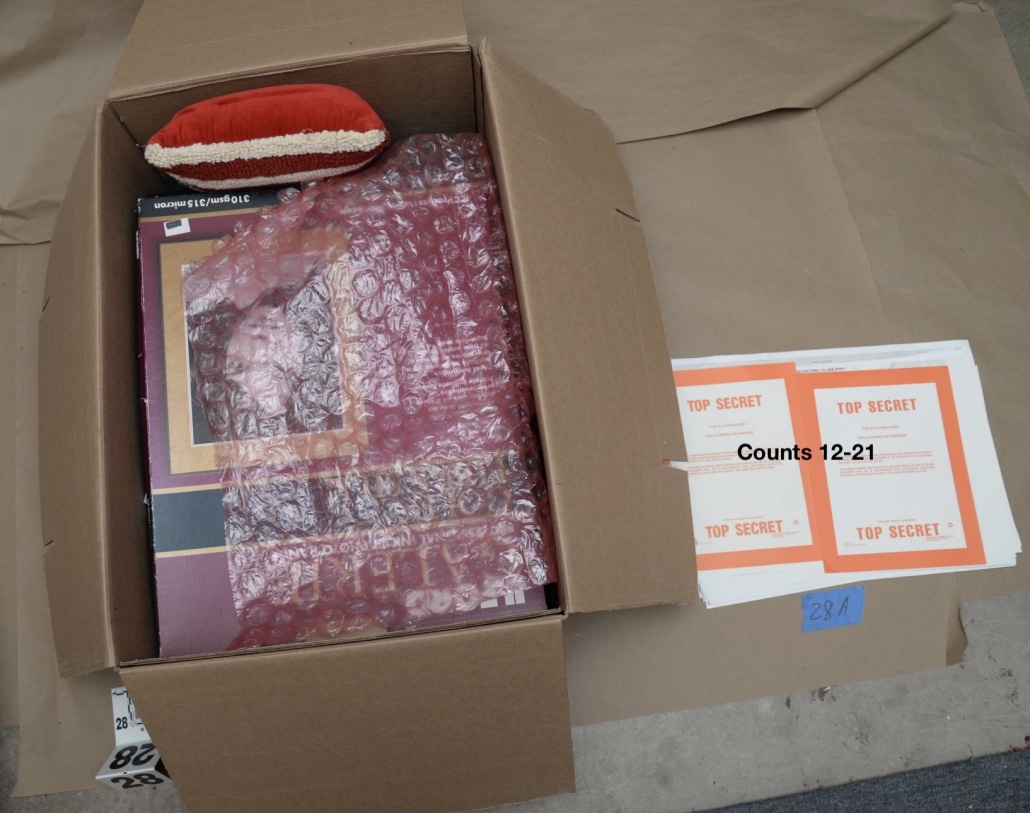

But the report is sure to be pretty damning. I’m virtually certain the report shows that aspiring FBI Director Kash Patel lied to help Trump retain classified documents. Senior White House counselor designee Stan Woodward played a role in giving Patel and Walt Nauta legal protection to, themselves, run legal interference for Trump (though there’s absolutely no reason to believe the report will say Woodward’s actions were unethical). Questions remain about whether Trump succeeded in retaining and disposing of still-unidentified documents. And the report may explain the sensitivities of the documents and the mitigation the Intelligence Community had to do as a result.

That said, my dream convinced me — against my better judgment — to explain what I think DOJ is trying to do with this legal fight, because it conveys the outer limits of potential scandal that could be buried in that document. Just the stuff implicating Kash alone is damning, but it could be far worse.

I want to talk about the government response — in the person of the SDFL US Attorney’s Office and DOJ’s Appellate team, because Jack Smith has already withdrawn from the 11th Circuit — to Walt Nauta and Carlos De Oliveira’s bid to enjoin the release of the stolen documents half of the Jack Smith report.

Procedurally, here is what happened in the 11th Circuit (I may or may not go back to fill in Aileen Cannon’s side, but as you can see, she tried to bigfoot into an ongoing matter before the 11th Circuit, which may have pissed off the 11th).

January 7, 9:02 AM, 11th Circuit: Emergency motion to bar release. “Garland is certain to release the report and it will impugn on our right to a free trial and the report cannot be released lawfully, because Jack Smith was unconstitutionally appointed and Trump is President-elect.”

January 7, 1:13PM, 11th Circuit: Notice. DOJ shall submit a response by 10AM on January 8.

January 7, 1:23PM, 11th Circuit: USDC Order. Aileen Cannon’s order enjoining the release of everything docketed at 11th Circuit.

January 7, 1:28PM, 11th Circuit: Notice of appearance. DOJ Appellate lawyer Mark Freeman files an appearance.

January 7, 3:18PM, 11th Circuit: Supplemental. “Here’s the order that already got filed in this docket. We’re, uh, filing it so it has a procedural purpose on the docket.”

January 8, 9:49AM, 11th Circuit: Response. “The part of the report pertaining to Nauta and De Oliveira won’t be released so they have no standing.”

January 8, 11:28AM, 11th Circuit: Notice of intention to reply. “We’re going to reply by 10AM on Thursday.”

January 8, 12:22PM, 11th Circuit: Notice. “No, you’ve got until 5PM today to respond.”

January 8, 5:06PM, 11th Circuit: Reply. “What if it leaks?”

January 8, 10:52PM, 11th Circuit: Trump Amicus. “Block both volumes!!”

The government response effectively argues the following: There are two volumes to the report, Volume One, which covers Trump’s attempted coup, and Volume Two, which covers the documents case. Walt Nauta and Carlos De Oliveira are not mentioned in Volume One, and so they have no interest in it and so no legal standing to try to block it.

Because of the ongoing case against Nauta and De Oliveira (the Response explains), Merrick Garland has decided that no part of Volume Two will be released. It will, instead, only be made available for in camera review to the House and Senate Judiciary Chairs and Ranking Members at their request, with their agreement that no information from it will be publicly released.

Nauta and De Oliveira have no authority to affect the release of Volume One. Not only did Judge Cannon’s original order deeming the Jack Smith appointment unconstitutional limit itself to the case before her (that is, not even the one in DC), but she cannot have the authority to deem all Special Counsels unlawful.

Please specify that this is the last word, unless the 11th Circuit en banc or the Supreme Court tries to get involved.

Narrow the legal dispute

I don’t pretend any of this is satisfying to people who want both reports. But here’s the legal logic to it.

First, because of the the posture of this appeal, the entire documents side of the case is in uncertain status. When Judge Cannon ruled Jack Smith’s appointment was unconstitutional, she said that everything Smith had done since his appointment had to be unwound. So unless the report only covered stuff before that point — that is, through the document seizure, but during which Cannon’s injunction on the investigation largely prevented any interviews of people like Nauta — then it remains in limbo awaiting the 11th Circuit decision on Cannon’s ruling. So it’s not just that there’s a pending case against Nauta and De Oliveira, it’s also that the entire legal status of the work done after November 18, 2022, which makes up the bulk of the obstruction investigation.

So whatever Garland (or Brad Weinsheimer, the top nonpartisan lawyer at DOJ, whom I’m certain is involved) thinks about the merit of releasing the report, for the purposes of this dispute, he is trying to eliminate any standing anyone has to interfere with the release of the January 6 volume. (Side note: it was short-sighted for Jack Smith to release these as volumes to the same report, rather than separate free-standing reports.) Nothing Garland has authorized with the volume pertaining to Nauta and DeOliveira can affect their hypothetical right to a fair trial they’ll never face, because nothing from the report will become public in such a way that potential jurors would see it. That is, sacrifice immediate publication of the documents volume in an attempt to release the January 6 one.

Create a dead man’s switch

Garland has agreed with Jack Smith that Volume Two should not be released so long as the Nauta and De Oliveira cases are pending, but that suggests once they no longer are pending, the information could be released.

Attorney General Garland is committed to ensuring the integrity of the Department’s criminal prosecutions. Considering the risk of prejudice to defendants Nauta’s and De Oliveira’s criminal case, the Attorney General has agreed with the Special Counsel’s recommendation that Volume Two of the Final Report should not be publicly released while those cases remain pending. See 28 C.F.R. § 600.9(c). There is therefore no risk of prejudice to defendants and no basis for an injunction against the Attorney General.

[snip]

The Attorney General’s determination not to authorize the public release of Volume Two fully addresses the harms that defendants seek to avoid in their emergency motion. As noted, consistent with 28 C.F.R. 600.9(a), the Attorney General intends to make Volume Two of the Final Report available for in camera review by the Chairmen and Ranking Members of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, pursuant to restrictions to protect confidentiality. Even then, however, consistent with legal requirements, the Department will redact grand jury information protected by Rule 6(e) as well as information sealed by court order from the version made available in camera for congressional review. Defendants have no colorable claim to prejudice from these carefully circumscribed in camera disclosures.

The filing leaves unsaid what happens when the cases against them go away, which will happen either because the 11th Circuit affirms Cannon’s ruling that Jack Smith was unlawfully appointed, Trump’s DOJ withdraws from the appeal, or Trump simply pardons his co-conspirators. Everyone knows they will go away, but once they do, then in theory Volume Two could come out.

Everyone has made sure the report could come out in current form; because of the redactions they’ve done, no grand jury material would be implicated, nor any information sealed by Cannon.

This creates an effective dead man’s switch tied to the Nauta and De Oliveira prosecution. Once that case goes away, Jamie Raskin and Dick Durbin would be free to talk about it. And, it’s possible, there’s a standing order at DOJ that it will be released publicly.

Of course, either the landing team at DOJ or Pam Bondi, once she’s confirmed, can and undoubtedly would override any such order. Assuming they can find every report at DOJ or they disseminate an order forbidding its release sufficiently broadly to cover all potential distributions within DOJ, they can and likely will succeed in preventing the release.

I’m not saying we’ll get the report, which is one reason I hesitated to even post this.

At that point, though, whoever orders the report’s suppression would, in effect, be suppressing damning information about — at least — Kash Patel. And Trump. And (with my clear caveat that there’s no reason to believe Woodward did anything unethical), Woodward, who one of these days should expect nomination as a judge.

And, if Jamie Raskin and Dick Durbin get to review it, they would know that.

In other words, if, by taking any legal dispute off the table, Garland succeeds in letting Raskin and Durbin read the report, it’ll create a headache.

Not to mention, the existence of the report will likely form a key part of Jim Jordan and Kash Patel’s efforts to retaliate against Jay Bratt and Jack Smith. And it may create ethical obligations to recuse from such matters for everyone but Bondi.

Again, I’m not saying this will work. I’m saying it may cause headaches.

Implicate the Hunter Biden report

That brings us to the second thing that Garland/Weinsheimer have done to muddle these legal issues.

As I’ve said repeatedly, David Weiss was appointed under the same legal authority as Jack Smith. If Jack Smith’s appointment was unconstitutional, then Weiss’ was, too, especially with respect to Hunter Biden’s Los Angeles prosecution and even more with respect to Alexander Smirnov’s prosecution. Yet several DC judges have rejected that claim.

And we’re about to get a report from Weiss, too, one that remains unmentioned, at least specifically, in this legal dispute.

After Joe pardoned Hunter, Weiss got Smirnov to agree to a baffling above-guidelines sentence plea deal, with the caveat that he be sentenced almost immediately; yesterday, Judge Otis Wright sentenced him to six years. I expect that Weiss has already completed his report, with the expectation it’ll be released along with Trump ones on Friday. (I’ve been guessing this would all go down on January 10 for some time; looks like a pretty prescient guess.)

So when DOJ repeatedly mentions the impossibility that Cannon’s order could enjoin all Special Counsels nationwide, they are implicitly including David Weiss, even if only Jack Smith’s DC report gets mentioned.

Defendants also reiterate their claim that the Special Counsel was unlawfully appointed. The United States has thoroughly rebutted that contention in its merits briefs in this appeal. But in any event, the argument is irrelevant to the only action here at issue—the handling of the Final Report by the Attorney General. The district court, in dismissing the indictments against defendants, did not purport to enjoin the operations of the Special Counsel nationwide, nor could it have properly done so in this criminal case. Accordingly, as required by Department of Justice regulations, the Special Counsel duly prepared and transmitted his confidential Final Report to the Attorney General yesterday (as permitted by the district court’s recent order). 28 C.F.R. § 600.8(c) (“Closing documentation.”). What defendants now ask this Court to enjoin is not any action by the Special Counsel, but the Attorney General’s authority to decide whether to make such a report public. See id. § 600.9(c); 28 U.S.C. § 509. As noted above and discussed in more detail below, the Attorney General determined that he will not make a public release of Volume Two while defendants’ cases remain pending. That should be the end of the matter.

[snip]

Although the district court in this case concluded that the Special Counsel was not properly appointed and ordered that the indictment be dismissed as a remedy, the district court did not purport to enjoin the ongoing operations of the Special Counsel’s Office nationwide. This is a criminal case, and the district court limited its remedy to dismissal of the indictment. See Dkt. 672 at 93. The court did not purport to issue—and it could not properly have issued—a nationwide injunction barring the Special Counsel from discharging the functions of his office in Washington, D.C. or elsewhere.

Indeed, while defendants argue that the order appointing the Special Counsel became “void” upon issuance of the district court’s judgment in this case, Mot. 14, the district court was clear that its order was “confined to this proceeding,” see Dkt. 672 at 93. —i.e., to this criminal prosecution. The district court never barred the Special Counsel from performing other duties, including the preparation of the Final Report. Had it purported to do so, the district court would have had to grapple with the fact that the D.C. Circuit—whose law governs Department headquarters and the Special Counsel’s offices where the Final Report was prepared—has rejected the same Appointments Clause theory that the district court accepted. See, e.g., In re Grand Jury Investigation, 916 F.3d 1047, 1053 (D.C. Cir. 2019). The district court with responsibility for the Election Case did so as well.

On paper, at least, Nauta and De Oliveira have no legal dispute, and Trump’s amicus demanding that the DC volume be suppressed, too, has even less.

But who knows? Trump’s dealing with a set of judges and justices who could care less about legal standing if it means protecting him.

And that’s why the Hunter Biden report matters.

If the 11th Circuit issues an order enjoining all currently pending Special Counsel reports, it would have the effect of enjoining the Hunter Biden one, as well. And then, when Pam Bondi comes in and tries to suppress the Trump one, any release of the Hunter Biden one (which I expect to assign a specific time and cost value of the pardon to Hunter), will amount to an ethical problem, a double standard serving to protect Trump.

Again, I’m not saying that any of this will work. I’m saying that if and when it doesn’t, it has the ability create a big ethical and potentially legal headache for Trump’s wildly conflicted DOJ just at the start of their tenure.

Update (h/t Lemon Slayer): Garland wrote the Chairs and Ranking Members about the completion of the report and the delay caused by Cannon. This language sure sounds like Garland has intended his order will release the report when the investigation into Nauta and De Oliveira is killed.

Consistent with local court rules and Department policy, and to avoid any risk of prejudice to defendants Waltine Nauta and Carlos De Oliveira, whose criminal cases remain pending, I have determined, at the recommendation of the Special Counsel, that Volume Two should not be made public so long as those defendants’ criminal proceedings are ongoing. Therefore, when permitted to do so by the court, I intend to make available to you for in can1era review Volume Two of the Report upon your request and agreement not to release any information from Volume Two publicly. I have determined that once those criminal proceedings have concluded, releasing Volume Two of the Report to you and to the public would also be in the public interest, consistent with law and Department policy.