In a podcast with Preet Bharara this week, Sheldon Whitehouse had the following exchange about whether he thought Carter Page should have been surveilled. (after 24:30)

Whitehouse: I’ve got to be a little bit careful because I’m one of the few Senators who have been given access to the underlying material.

Bharara: Meaning the affidavit in support of the FISA application.

Whitehouse And related documents, yes. The package.

Bharara: And you’ve gone to read them?

Whitehouse: I’ve gone to read them.

Bharara: You didn’t send Trey Gowdy?

Whitehouse: [Laughs] I did not send Trey Gowdy. I actually went through them. And, so I’ve got to be careful because some of this is still classified. But the conclusion that I’ve reached is that there was abundant evidence outside of the Steele dossier that would have provoked any responsible FBI with a counterintelligence concern to look at whether Carter Page was an undisclosed foreign agent. And to this day the FBI continues to assert that he was a undisclosed Russian foreign agent.

For the following discussion, then, keep in mind that a very sober former US Attorney has read the case against Carter Page and says that the FBI still — still, after Page is as far as we know no longer under a FISA order — asserts he “was” an undisclosed foreign agent (it’s not clear what that past tense “was” is doing, as it could mean he was a foreign agent until the attention on him got too intense or remains one; also, I believe John Ratcliffe, a Republican on the House Judiciary Committee and also a former US Attorney, has read the application too).

With that background, I’d like to turn to the substance of the dispute between Chuck Grassley and Dianne Feinstein over the dossier, which has played out in the form of a referral of Christopher Steele to FBI for lying. In the wake of the Nunes memo theatrics, Grassley released first a heavily redacted version of the referral he and Lindsey Graham sent the FBI in early January, followed by a less-redacted version this week. The referral, even as a transparent political stunt, is nevertheless more substantive than Devin Nunes’ memo, leading some to take it more seriously. Which may be why Feinstein released a rebuttal this week.

In case you’re wondering, I’m tracking footnote escalation in these documents. They line up this way:

- 0: Nunes memo (0 footnotes over 4 pages, or 1 over 6 if you count Don McGahn’s cover letter)

- 2.6: Grassley referral (26 footnotes over 10 pages)

- 3.6: Schiff memo (36 footnotes, per HPSCI transcript, over 10 pages)

- 5.4: Feinstein rebuttal (27 footnotes over 5 pages)

So let me answer a series of questions about the memo as a way of arguing that, while by all means the FBI’s use of consultants might bear more scrutiny, this is still a side-show.

Did Christopher Steele lie?

The Grassely-Graham referral says Steele may have lied, but doesn’t commit to whether classified documents obtained by the Senate Judiciary Committee (presumably including the first two Page applications), a declaration Steele submitted in a British lawsuit, or Steele’s statements to the FBI include lies.

The FBI has since provided the Committee access to classified documents relevant to the FBI’s relationship with Mr. Steele and whether the FBI relied on his dossier work. As explained in greater detail below, when information in those classified documents is evaluated in light of sworn statements by Mr. Steele in British litigation, it appears that either Mr. Steele lied to the FBI or the British court, or that the classified documents reviewed by the Committee contain materially false statements.

On September 3, 2017 — a good three months before the Grassley-Graham referral — I pointed to a number of things in the Steele declaration, specifically pertaining to who got the dossier or heard about it when, that I deemed “improbable.”

That was the genius of the joint (!!) Russian-Republican campaign of lawfare against the dossier. As Steele and BuzzFeed and Fusion tried to avoid liability for false claims against Webzilla and Alfa Bank and their owners, they were backed into corners where they had to admit that Democrats funded the dossier and made claims that might crumble as Congress scrutinized the dossier.

So, yeah, I think it quite possible that Steele told some stretchers.

Did Christopher Steele lie to the FBI?

But that only matters if he lied to the FBI (and not really even there). The UK is not about to extradite one of its former spies because of lies told in the UK — they’re not even going to extradite alleged hacker Lauri Love, because we’re a barbaric country. And I assume the Brits give their spooks even more leeway to fib a little to courts than the US does.

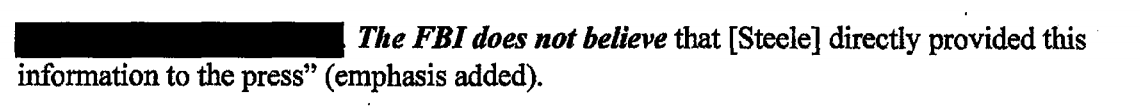

The most critical passage of the referral on this point, which appears to make a claim about whether Steele told the FBI he had shared information with the press before they first used his dossier in a Page application, looks like this.

The footnote in the middle of that redacted passage goes to an unredacted footnote that says,

The FBI has failed to provide the Committee the 1023s documenting all of Mr. Steele’s statements to the FBI, so the Committee is relying on the accuracy of the FBI’s representation to the FISC regarding the statements.

1023s are Confidential Human Source reports.

I say that’s the most important passage because the referral goes on to admit that in subsequent FISA applications the FBI explained that the relationship with Steele had been terminated because of his obvious involvement in the October 31, 2016 David Corn story. Graham and Grassley complain that the FBI didn’t use Steele’s defiance of the FBI request not to share this information with anyone besides the FBI to downgrade his credibility rankings. Apparently FISC was less concerned about that than Graham and Grassley, which may say more about standards for informants in FISA applications than Steele or Carter Page.

The footnote, though, is the biggest tell. That’s because Feinstein’s rebuttal makes it quite clear that after Grassley and Graham made their referral, SJC received documents — which, given what we know has been given to HPSCI, surely include those 1023s — that would alter the claims made in the referral.

The Department of Justice has provided documents regarding its interactions with Mr. Steele to the Judiciary Committee both before and after the criminal referral was made. Despite this, the Majority did not modify the criminal referral and pressed forward with its original claims, which do not take into account the additional information provided after the initial January 4 referral.

Feinstein then goes on to state, several times and underlining almost everything for emphasis, that the referral provides no proof that Steele was ever asked if he had served as the source for Isikoff.

- Importantly, the criminal referral fails to identify when, if ever, Mr. Steele was asked about and provided a materially false statement about his press contacts.

- Tellingly, it also fails to explain any circumstances which would have required Mr. Steele to seek the FBI’s permission to speak to the press or to disclose if he had done so.

[snip]

But the criminal referral provides no evidence that Steele was ever asked about the Isikoff article, or if asked that he lied.

In other words, between the redacted claim about what Steele said and Feinstein’s repeated claims that the referral presents no evidence Steele was asked about his prior contacts with the press, the evidence seems to suggest that Steele was probably not asked. And once he was, after the Corn article, he clearly did admit to the FBI he had spoken with the press. So while it appears Steele blew off the FBI’s warnings not to leak to the press, the evidence that he lied to the FBI appears far weaker.

Does it harm the viability of the FISA application?

That should end the analysis, because the ostensible purpose of the referral is a criminal referral, not to make an argument about the FISA process.

But let’s assess the memo’s efforts to discredit the FISA application.

In two places, the referral suggests the dossier played a bigger role in the FISA application than, for example, Whitehouse suggests.

Indeed, the documents we have reviewed show that the FBI took important investigative steps largely based on Mr. Steele’s information–and relying heavily on his credibility.

[snip]

Mr. Steele’s information formed a significant portion of the FBI’s warrant application, and the FISA application relied more heavily on Steele’s credibility than on any independent verification or corroboration for his claims. Thus the basis for the warrant authorizing surveillance on a U.S. citizen rests largely on Mr. Steele’s credibility.

These claims would be more convincing, however, if they acknowledged that FBI had to have obtained valuable foreign intelligence off their Page wiretap over the course of the year they had him wiretapped to get three more applications approved.

Indeed, had Grassley and Graham commented on the addition of new information in each application, their more justifiable complaint that the FBI did not alert FISC to the UK filings in which Steele admitted more contact with the press than (they claim) show up in the applications would be more compelling. If you’re going to bitch about newly learned information not showing up in subsequent applications, then admit that newly acquired information showed up.

Likewise, I’m very sympathetic with the substance of the Grassley-Graham complaint that Steele’s discussions with the press made it more likely that disinformation got inserted into the dossier (see my most recently post on that topic), but I think the Grassley-Graham complaint undermines itself in several ways.

Simply put, the more people who contemporaneously knew that Mr. Steele was compiling his dossier, the more likely it was vulnerable to manipulation. In fact, the British litigation, which involves a post-election dossier memorandum, Mr. Steele admitted that he received and included in it unsolicited–and unverified–allegations. That filing implies that implies that he similar received unsolicited intelligence on these matters prior to the election as well, stating that Mr. Steele “continued to receive unsolicited intelligence on the matters covered by the pre-election memoranda after the US Presidential election.” [my underline]

The passage is followed by an entirely redacted paragraph that likely talks about disinformation.

This is actually an important claim, not just because it raises the possibility that Page might be unfairly surveilled as part of a Russian effort to distract attention from others (though its use in a secret application wouldn’t have sown the discord it has had it not leaked), but also because we can check whether their claims hold up against the Steele declaration. It’s one place we can check the referral to see whether their arguments accurately reflect the underlying evidence.

Importantly, to support a claim the potential for disinformation in the Steele dossier show up in the form of unsolicited information earlier than they otherwise substantiate, they claim a statement in Steele’s earlier declaration pertains to pre-election memos. Here’s what it looks like in that declaration:

That is, Steele didn’t say he was getting unsolicited information prior to the election; this was, in both declarations, a reference to the single December report.

Moreover, while I absolutely agree that the last report is the most likely to be disinformation, the referral is actually not clear whether that December 13 report ever actually got included in a FISA application. There’s no reason it would have been. While the last report mentions Page, the mention is only a referral back to earlier claims that Trump’s camp was trying to clean up after reports of Page’s involvement with the Russians got made public. So the risk that the December memorandum consisted partially or wholly of disinformation is likely utterly irrelevant to the validity of the three later FISA orders targeting Page.

Which is to say that, while I think worries about disinformation are real (particularly given their reference to Rinat Akhmetshin allegedly learning about the dossier during the summer, which I wrote about here), the case Grassley and Graham make on that point both miscites Steele’s own declaration and overstates the impact of their argued case on a Page application.

What about the Michael Isikoff reference?

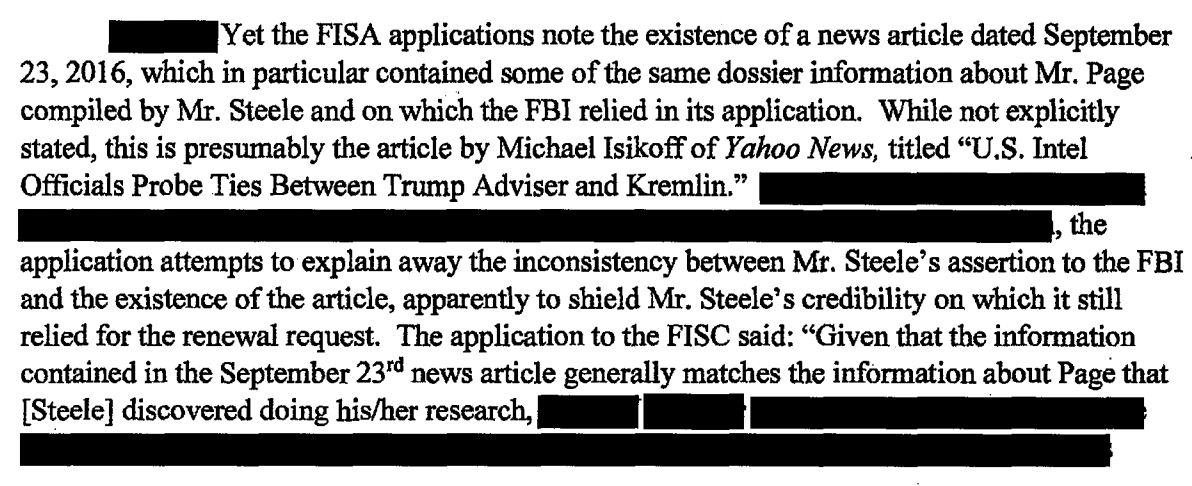

Perhaps the most interesting detail in the Grassley-Graham referral pertains to their obsession with the applications’ references to the September 23 Michael Isikoff article based off Steele’s early discussions with the press. Grassley-Graham claim there’s no information corroborating the dossier (there’s a redacted Comey quote that likely says something similar). In that context, they point to the reference to Isikoff without explaining what it was doing there.

The application appears to contain no additional information corroborating the dossier allegations against Mr. Page, although it does cite to a news article that appears to be sourced to Mr. Steele’s dossier as well.

Elsewhere, I’ve seen people suggest the reference to Isikoff may have justified the need for secrecy or something, rater than as corroboration. But neither the referral nor Feinstein’s rebuttal explains what the reference is doing.

In this passage, Grassley and Graham not only focus on Isikoff, but they ascribe certain motives to the way FBI referred to it, suggesting the claim that they did not believe Steele was a source for Isikoff was an attempt to “shield Mr. Steele’s credibility.”

There’s absolutely no reason the FBI would have seen the need to shield Steele’s credibility in October. He was credible. More troubling is that the FBI said much the same thing in January.

In the January reapplication, the FBI stated in a footnote that, “it did not believe that Steele gave information to Yahoo News that ‘published the September 23 News Article.”

Let’s do some math.

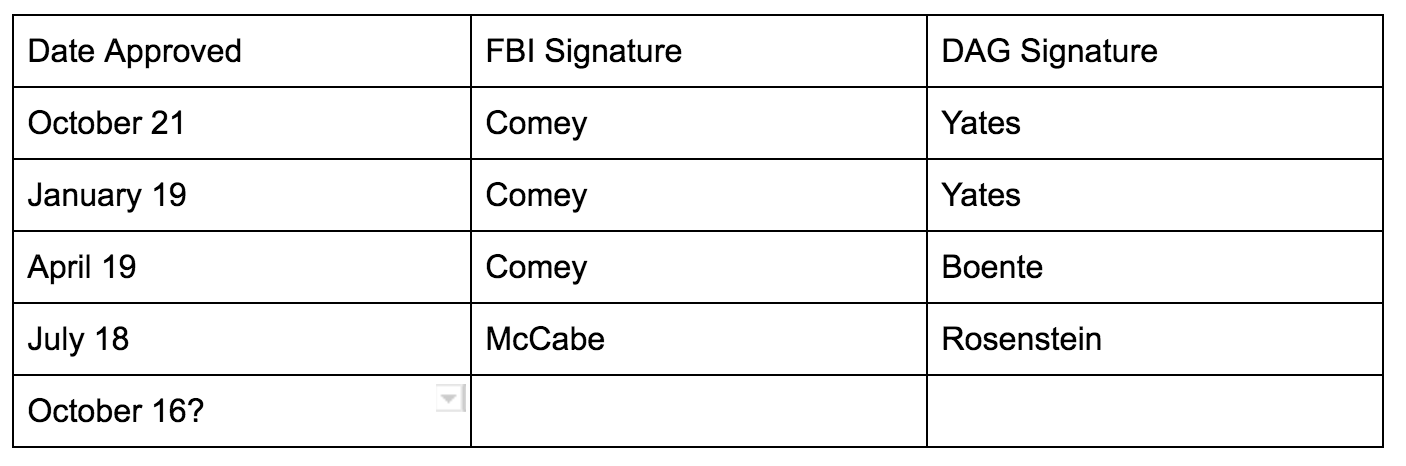

If I’m doing my math correctly, if the FISA reapplications happened at a regular 90 day interval, they’d look like this.

That’d be consistent with what the Nunes memo said about who signed what, and would fit the firing dates of January 30 for Yates and May 9 for Comey, as well as the start date for Rosenstein of April 26 (Chris Wray started on August 1).

If that’s right, then Isikoff wrote his second article on the Steele dossier, one that made it clear via a link his earlier piece had been based off Steele, before the second application was submitted (though the application would have been finished and submitted in preliminary form a week earlier, meaning FBI would have had to note the Isikoff piece immediately to get it into the application, but the topic of the Isikoff piece — that Steele was an FBI asset — might have attracted their attention).

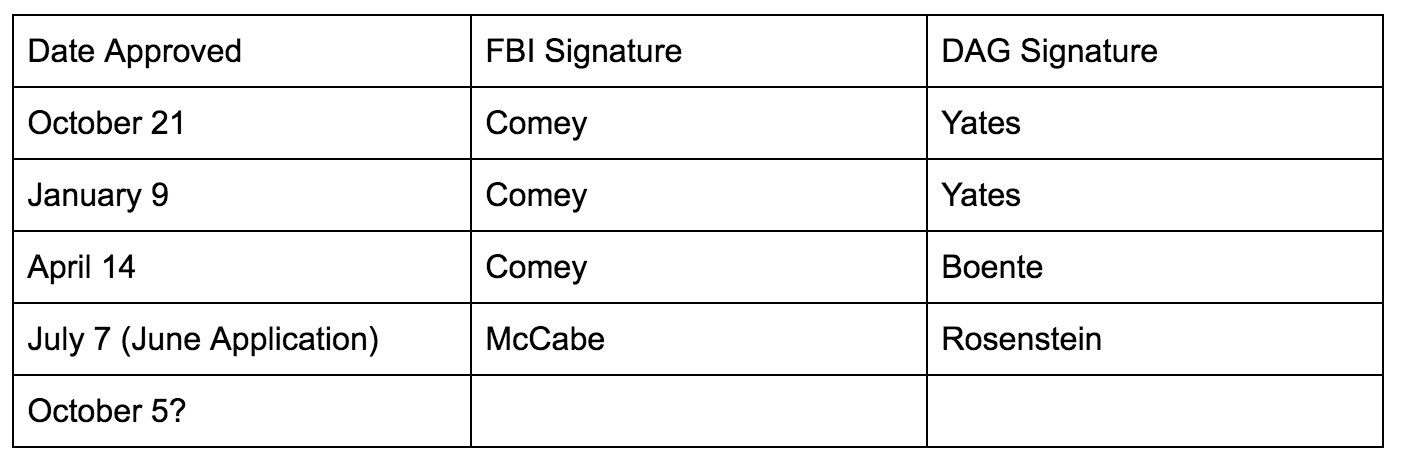

But that’s probably not right because the Grassley-Graham referral describes a June, not July, reapplication, meaning the application would have been no later than the last week of June. That makes the reauthorization dates look more like this, distributing the extra days roughly proportionately:

That would put the second footnote claiming the FBI had no reason to believe the September Isikoff piece was based on Steele before the time when the second Isikoff piece made it clear.

I’m doing this for a second reason, however. It’s possible (particularly given Whitehouse’s comments) Carter Page remains under surveillance, but for some reason it’s no longer contentious.

That might be the case if the reapplications no longer rely on the dossier.

And I’m interested in that timing because, on September 9, I made what was implicit clear: That pointing to the September Isikoff piece to claim the Steele dossier had been corroborated was self-referential. I’m not positive I was the first, but by that point, the Isikoff thing would have been made explicit.

Does this matter at all to the Mueller inquiry?

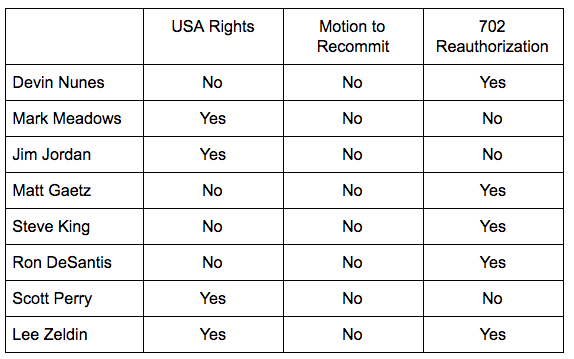

Ultimately, though, particularly given the Nunes memo confirmation that the counterintelligence investigation into Trump’s people all stems from the George Papadopoulos tip, and not Page (particularly given the evidence that the FBI was very conservative in their investigation of him) there’s not enough in even the Grassley-Graham referral to raise questions about the Mueller investigation, especially given a point I made out in the Politico last week.

According to a mid-January status report in the case against Manafort and his deputy, Rick Gates, the government has turned over “more than 590,000 items” to his defense team, “including (but not limited to) financial records, records from vendors identified in the indictment, email communications involving the defendants, and corporate records.” He and Gates have received imaged copies of 87 laptops, phones and thumb drives, and copies off 19 search-warrant applications. He has not received, however, a FISA notice, which the government would be required to provide if they planned to use anything acquired using evidence obtained using the reported FISA warrant against Manafort. That’s evidence of just how much of a distraction Manafort’s strategy [of using the Steele dossier to discredit the Mueller investigation] is, of turning the dossier into a surrogate for the far more substantive case against him and others.

And it’s not just Manafort. Not a single thing in the George Papadopoulos and Michael Flynn guilty pleas—for lying to the FBI—stems from any recognizable mention in the dossier, either. Even if the Steele dossier were a poisoned fruit, rather than the kind of routine oppo research that Republicans themselves had pushed to the FBI to support investigations, Mueller has planted an entirely new tree blooming with incriminating details.

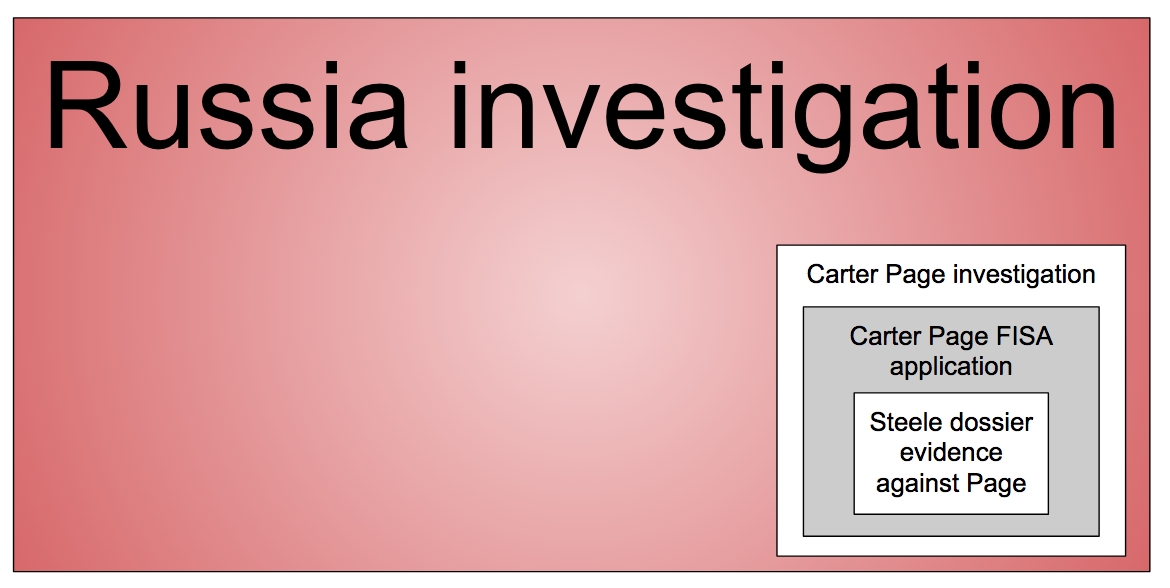

Thus the point of my graphic above. The Steele dossier evidence used in the Carter Page FISA application to support an investigation into Cater Page, no matter what else it says about the FISA application process or FBI candor, is just a small corner of the investigation into Trump’s people.