Why Read Old Books?

Trumpalooza 2020 and DemFest are over, the actual campaign is beginning, and I am overwhelmed by the crazy and stupid. I’ve been asking myslef whether it makes sense to continue this project of trying to understand our current morass and what we should do about it. Are old books worth reading in a time of troubles like ours?

One aspect of our current morass is the unwillingness of so many people to rethink any belief they hold. This is an old problem. There is no reason to think we can’t find helpful answers in the works of our ancestors from all times and places. Did Confucius know less about human nature than Aristotle? Did Sophocles understand people less well than Jane Austen?

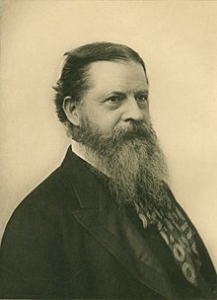

Charles Sanders Peirce

With these considerations in mind, here’s an extended quote from The Fixation of Belief by Charles Peirce, perhaps the earliest American Pragmatist, published in 1877.

If the settlement of opinion is the sole object of inquiry, and if belief is of the nature of a habit, why should we not attain the desired end, by taking as answer to a question any we may fancy, and constantly reiterating it to ourselves, dwelling on all which may conduce to that belief, and learning to turn with contempt and hatred from anything that might disturb it? This simple and direct method is really pursued by many men. I remember once being entreated not to read a certain newspaper lest it might change my opinion upon free-trade. “Lest I might be entrapped by its fallacies and misstatements,” was the form of expression. “You are not,” my friend said, “a special student of political economy. You might, therefore, easily be deceived by fallacious arguments upon the subject. You might, then, if you read this paper, be led to believe in protection. But you admit that free-trade is the true doctrine; and you do not wish to believe what is not true.” I have often known this system to be deliberately adopted.

Still oftener, the instinctive dislike of an undecided state of mind, exaggerated into a vague dread of doubt, makes men cling spasmodically to the views they already take. The man feels that, if he only holds to his belief without wavering, it will be entirely satisfactory. Nor can it be denied that a steady and immovable faith yields great peace of mind. It may, indeed, give rise to inconveniences, as if a man should resolutely continue to believe that fire would not burn him, or that he would be eternally damned if he received his ingestaITAL otherwise than through a stomach-pump. But then the man who adopts this method will not allow that its inconveniences are greater than its advantages. He will say, “I hold steadfastly to the truth, and the truth is always wholesome.”

And in many cases it may very well be that the pleasure he derives from his calm faith overbalances any inconveniences resulting from its deceptive character. Thus, if it be true that death is annihilation, then the man who believes that he will certainly go straight to heaven when he dies, provided he have fulfilled certain simple observances in this life, has a cheap pleasure which will not be followed by the least disappointment. A similar consideration seems to have weight with many persons in religious topics, for we frequently hear it said, “Oh, I could not believe so-and-so, because I should be wretched if I did.”

When an ostrich buries its head in the sand as danger approaches, it very likely takes the happiest course. It hides the danger, and then calmly says there is no danger; and, if it feels perfectly sure there is none, why should it raise its head to see? A man may go through life, systematically keeping out of view all that might cause a change in his opinions, and if he only succeeds — basing his method, as he does, on two fundamental psychological laws — I do not see what can be said against his doing so. It would be an egotistical impertinence to object that his procedure is irrational, for that only amounts to saying that his method of settling belief is not ours. He does not propose to himself to be rational, and, indeed, will often talk with scorn of man’s weak and illusive reason. So let him think as he pleases.

Peirce calls this the method of tenacity. Underlying it is Peirce’s view, which seems right to me, that when we begin to think for ourselves, when we become individuated, we already have a set of beliefs about the world. As we take in new data, we try to incorporate the new information into our existing set of ideas. Or maybe, as the ostrich, we don’t.

Obviously tenacity has some value. Our beliefs are hard-won assets, and we don’t want to give them up without a good reason. I think our first response to new data is often to apply the method of tenacity. The more dense our web of knowledge and belief, the harder it is to adjust, and the more tightly we cling to our existing beliefs.

There is a problem with the method of tenacity. Peirce says that it’s hard to hold to this method when you rub up against other human beings who don’t hold to the same beliefs.

But why exactly do people change their minds? Peirce says we like our beliefs to be internally consistent and coherent with what we observe. He thinks we are more likely to improve our outcomes if we do this. That makes sense in the context of science and academics, but not so much in day-to-day life. Does Jane Austen have something to add?

Jane Austen, portrait by her sister Casssandra.

In Pride and Prejudice, two of the characters, Darcy and Elizabeth, actually change in crucial ways and for the better. [1] Austen makes it clear that the characters change themselves using the method Peirce approves, careful observation of the external world and intentional incorporation of those observations into or in place of previously held views of the self.

The context is that the two have been jousting with words over several meetings. Darcy’s admiration for Elizabeth is growing, but she is only interested in the battle of wits, and is unaware of his growing infatuation. Then Darcy proposes marriage in a wonderful scene. Elizabeth is shocked, and insulted by the form of the proposal. They fight. Here’s the conclusion.

Elizabeth felt herself growing more angry every moment; yet she tried to the utmost to speak with composure when she said:

“You are mistaken, Mr. Darcy, if you suppose that the mode of your declaration affected me in any other way, than as it spared me the concern which I might have felt in refusing you, had you behaved in a more gentlemanlike manner.”

She saw him start at this, but he said nothing, and she continued:

“You could not have made the offer of your hand in any possible way that would have tempted me to accept it.”

Again his astonishment was obvious; and he looked at her with an expression of mingled incredulity and mortification. She went on:

“From the very beginning—from the first moment, I may almost say—of my acquaintance with you, your manners, impressing me with the fullest belief of your arrogance, your conceit, and your selfish disdain of the feelings of others, were such as to form the groundwork of disapprobation on which succeeding events have built so immovable a dislike; and I had not known you a month before I felt that you were the last man in the world whom I could ever be prevailed on to marry.”

Darcy is one of the wealthiest men in England, and as we see later is a man of taste and discrimination, versed in business and society. Elizabeth is a gentlewoman, but she has no future if she doesn’t marry. Rejecting Darcy is a very serious step.

The next morning Darcy hands her a letter explaining his actions in the two matters that formed the basis for her rejection. Elizabeth reads the letter, and considers carefully the new information against the beliefs she holds about the events. In each particular raised by the letter she sees that Darcy’s explanation offers a better, more coherent and more likely accurate view.

“How despicably I have acted!” she cried; “I, who have prided myself on my discernment! I, who have valued myself on my abilities! who have often disdained the generous candour of my sister, and gratified my vanity in useless or blameable mistrust! How humiliating is this discovery! Yet, how just a humiliation! Had I been in love, I could not have been more wretchedly blind! But vanity, not love, has been my folly. Pleased with the preference of one, and offended by the neglect of the other, on the very beginning of our acquaintance, I have courted prepossession and ignorance, and driven reason away, where either were concerned. Till this moment I never knew myself.”

Her self-reflection form the basis of her re-evaluation of Darcy as a person.

Darcy is deeply affected by Elizabeth’s rejection. He explains his feelings at the end of the book. This quote gives the flavor.

“I cannot be so easily reconciled to myself. The recollection of what I then said, of my conduct, my manners, my expressions during the whole of it, is now, and has been many months, inexpressibly painful to me. Your reproof, so well applied, I shall never forget: ‘had you behaved in a more gentlemanlike manner.’ Those were your words. You know not, you can scarcely conceive, how they have tortured me;—though it was some time, I confess, before I was reasonable enough to allow their justice.”

Again, we see that he has followed Peirce in re-examining his actions in Elizabeth’s company and in general. It leads him to reinterpret his his behavior, not just toward Elizabeth but in general. And then he recognizes he needs to change, and does so.

But why did they change? I think it’s because both of them have see themselves as intellectually honest in the way Perice recommends. That means facing the facts we perceive, not hiding from those that imperil our current beliefs and opinions. In Darcy’s case, there’s another obvious motivation. He likes and admires Elizabeth, much to his surprise. He admires her fine eyes and her light figure, but mostly he admires her quick wit and understanding. Even after she rejects him that admiration continues. He is certain that he was right to admire her, and that forces him to face himself and his actions squarely as she sees them.

This is also true for Elizabeth, if less obvious. “His attachment excited gratitude, his general character respect; but she could not approve him….” This motivates her to consider carefully his explanations and his observations. It also motivates her to change.

Over time they recognize the strengths and weaknesses in themselves and each other, and they each see that the other is a good match. I think Darcy recognizes that this new self-understanding will make hem a better person.

I was given good principles, but left to follow them in pride and conceit. Unfortunately an only son (for many years an only child), I was spoilt by my parents, who, though good themselves (my father, particularly, all that was benevolent and amiable), allowed, encouraged, almost taught me to be selfish and overbearing; to care for none beyond my own family circle; to think meanly of all the rest of the world; to wish at least to think meanly of their sense and worth compared with my own. Such I was, from eight to eight and twenty; and such I might still have been but for you, dearest, loveliest Elizabeth! What do I not owe you! You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous. By you, I was properly humbled. I came to you without a doubt of my reception. You showed me how insufficient were all my pretensions to please a woman worthy of being pleased.”

Elizabeth sees the value of Darcy:

She began now to comprehend that he was exactly the man who, in disposition and talents, would most suit her. His understanding and temper, though unlike her own, would have answered all her wishes. It was an union that must have been to the advantage of both; by her ease and liveliness, his mind might have been softened, his manners improved; and from his judgement, information, and knowledge of the world, she must have received benefit of greater importance.

There’s a lesson here….

=====

[1] If you haven’t read this book, or haven’t read it lately, I highly recommend it as part of a mental cleansing.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia-80x80.jpg)

I enjoy reading “Pride & Prejudice”, and also “Persuasion”.

(This week I’ve seen recommendations for Shelley’s “Frankenstein” as being both very worth reading and also still timely.)

Frankenstein has powerful passages, but for a modern reader it has a complex narrative setup, with boxes inside boxes, so to speak, and that can be hard to get through. Once you penetrate to the inner story, however, it has an undeniable forward momentum and some great individual scenes. “It was on a cold night in November that I first beheld the result of all my labours,” etc etc. Paraphrased since I haven’t read it in years.

Slightly OT, but does anyone other than myself collect interesting first lines of novels? (The above is not the first line as published, but the first line written.)

The first line makes or breaks novels. Publishers can be sold immediately on a book with a really captivating first line.

In the case of Pride and Prejudice, the first line is one of the most memorable in all English language literature:

The first line of P&P also distinguishes it from all the rest of Austen’s works because it both establishes a socioeconomic manifesto around which the work hangs and launches immediately into dialog. By comparison the rest of her works open with exposition.

I think a first line I’ve long enjoyed is worth revisiting now: “It was a pleasure to burn.” Those six words say so much with genius economy about what will follow in Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451.

“A screaming comes across the sky.”

The first line of Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon.

That one’s so good, cuts incisively. To write something like that as a first line would be grand.

And I, I collect the first lines of songs:

“The screen door slams, Mary’s dress waves …”

“I was born, inna crossfire hurricane …”

“There’s a lady who’s sure, all that glitters is gold …”

“I said, certified freak …”

The opposite of brevity but a long forgotten first line for 2020 from A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

The opening sentence/poem from the Great Gatsby, also so applicable to 2020:

“Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!”

Yes! Whether you loved or hated Tale Of Two Cities overall, and I recall a bit of both personally, that opening has to be at or near the top of all time.

Every time I read that opening sentence-graf to Dicken’s A Tale of Two Cities I can’t help think of a particular biblical verse:

I’ve always wondered if Dickens was inspired by the oppositions listed in Ecclesiastes, and if he used similar inspiration from other texts in his work.

“Marley was dead, to begin with.” Another opening line by Dickens.

He makes you wait until the fourth paragraph to learn why that’s important: “There is no doubt that Marley was dead. This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate.” But that would be a less haunting first line.

First known to many as, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” … (adapted by Pete Seeger, 1962, then Judy Collins, The Byrds, etc.)

And then some books, Gravity’s Rainbow in particular, might do their readers a favor by having a less compelling first line ;-)

[though I often recall another line from somewhere in the middle of Gravity’s Rainbow; something like, “A dream of competence, too closely examined”]

Tremendous first line in Gravity’s Rainbow! Now, if only I could finish the rest of the lines.

FWIW, I read the first 50 pages at least 4 times before I could keep going.

Pynchon’s first novel “V” is also massive and slow to build, but I enjoyed it and Gravity’s Rainbow.

In a similar vein, John Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest.”

Not the first line, but for me unforgettable: ‘”I would set you free, if I knew how. But it isn’t free out here. All the animals, the plants, the minerals, even other kinds of men, are being broken and reassembled every day, to preserve an elite few, who are the loudest to theorize on freedom, but the least free of all. I can’t even give you hope that it will be different someday – that They’ll come out, and forget death, and lose Their technology’s elaborate terror, and stop using every other form of life without mercy to keep what haunts men down to a tolerable level – and be like you instead, simply here, simply alive….”‘ from Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon

That is fabulous. Thanks.

Hear ye! The Crying of Lot 49 is my favorite Pynchon novel. Short, often hilarious, groovy, flagrantly original. I’ve taught it many times and my students actually enjoyed it, kind of an antidote to the downer 1960s in Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays (another book of that vintage I love).

“It was a dark and stormy night.” Opening line to Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel, “Paul Clifford”, from 1830.

LOL that snippet is what sticks with people 190 years later, but the full first line to that novel is much longer:

Ah, what spectacular purple prose.

It really does set the scene, though. (I read words and get pictures in my head. This paragraph isn’t all that purple.)

I guess back then when you undertook to read a novel, you really got your money’s worth. None of this minimalist prose nonsense. ; – )

Two more serious nominees for famous opening sentences would be:

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” from “Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy (trans. by Constance Garnett) and ….

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” from “Rebecca” by Daphne du Maurier

Published as serials – paid by the word (as magazines still pay).

So spectacular that the award for writing the most atrocious opening sentence in a fictional novel is named after him. https://www.bulwer-lytton.com/ The cringe-worthy 2020 winner:

Makes you want to bank off of a northeast wind, sail on a summer breeze, and skip over the ocean like a stone – and leave the pizza unambiguously behind. https://genius.com/Harry-nilsson-everybodys-talkin-lyrics

Just started reading “The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age” by Leo Damrosch published last year. Damrosch describes the period of Johnson’s life when he wrote series of short essays under the sobriquet of ‘The Idler’ and refers to one in which:

‘An imaginary male correspondent writes, “I was known to possess a fortune, and to want a wife.” This might have been in the mind of Jane Austen, an admirer of Johnson’s writing, when she wrote the famous opening sentence of “Pride and Prejudice”…’

Or so speculates Mr. Damrosch.

LOL Not just Damrosch but Isobel Grundy in her essay, “Jane Austen and literary traditions,” c. 1997. I don’t know that Austen was necessarily inspired by Johnson though she may indeed have been thinking of his line.

Incited to snark, perhaps, because OF COURSE, a single man of good fortune must be in want of female human chattel, I mean, a wife.

Austen probably also drew on Fielding’s “Tom Jones: A Foundling”, which also has elements of socioeconomic injustice and is wittier than I can attest.

Apparently, Jane often read to her sister, mother, and assembled family in the evenings. She definitely wrote for the ear. As did Fielding.

Though not a book, a movie, the word “rosebud” in Citizen Kane has to be one of the most powerful beginnings and endings in story telling of the 20th century and the story itself one of the most powerful morality tales of the 20th century. The story depicts the sad shallowness that to often accompanies vast wealth and power.

Though Academy Award winning, it’s a thinly veiled harsh commentary on the life of William Randolph Hearst. This resulted in Orson Welles being black listed in the movie industry the rest of his life.

‘Rosebud’ had very specific meaning to Hearst which contributed to his rage at Welles and the movie.

The best first line I ever read:

One Hundred Years of Solitude

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.

And, of course, we must have it in the original Spanish:

Cien Años de Soledad

Muchos años después, frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, el coronel Aureliano Buendía había de recordar aquella tarde remota en que su padre lo llevó a conocer el hielo.

Read all about it here: https://lithub.com/on-the-iconic-first-line-of-one-hundred-years-of-solitude/

The Shelley line is what I put in my daughter’s birthday card every fall (Nov baby), she is a bibliophile with a twisted parent…

It was Mary Shelley’s 223rd birth day on August 30. Always a good day to revisit her work — this year especially since she wrote a second work of science fiction, an apocalyptic, dystopian novel about the post-pandemic 21st century. You can download and read The Last Man for free via Project Gutenberg.

The birthday entry at File 770:

(“Us” is the science fiction and fantasy community.)

~shaking my head~ It’s so glaringly obvious when white men in SFF write about Mary Shelley.

Frankenstein isn’t the first science fiction novel; another woman, Margaret Cavendish, beat her to it by more than 100 years with The Blazing World. Feminist tract? I doubt he could point out what makes it so apart from a woman author.

Persuasion is my second-favorite Austen. I recently listened to a Librivox version while trying to get a bit of exercise while gyms were closed. We watched the Amanda Root/Ciaran Hinds movie. It offers a study of the need to throw off the demands made by family and society. The last scene of the movie is touching and happy.

Oh jeez, I am move-ed (pronounce that like an Elizabethan, with emphasis on first of two syllables) every time I read Wentworth’s letter: … You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. …

Gah. ~swoons~

Well and truly said

I have been lurking here for a long time — intimidated to think that I might have something to add. So I will start by noting that my mother tried to get me to read P&P when I was thirteen, telling me it was one of her favorite books. I could not get past the title; I did not even open it to page one. I was a stupid, young teenager.

Four years later I found it on my bookshelf, and could not put it down until I had finished. The transformations of Darcy and Elizabeth happen because, as you point out (in a clear way that I have not been able to express before when recommending the book to friends), they both see themselves as being intellectually honest (and, I would add, they try to live up to that ideal by doing something that is very hard: looking inward with a critical eye).

Thank you for a wonderful post!

I recently found a beautiful edition of The Red and the Black by Stendhal in my bookcase. After it sat with on my bedside table for a month I have finally started reading it. While it felt quaint and archaic in the beginning I have just realized a parallel to explain one of my most profound and vexing relationships.

I haven’t re-read that one in decades. Been thinking about reading it against Samuel Richardson’s Pamela for comparison.

Me too! The translation I read was by C.K. Scott-Moncreiff, and I recall it was creaky. I read his translation of Remembrance of Things Past. I think if I reread it I’ll check one of the recent translations.

Project Gutenberg has both the original French Le Rouge et Le Noir as well as a 1916 English translation by Horace B. Samuel. (I know nothing at all about Samuel, sad to say, can’t readily find much info about him, either.) It’s already fun to open them both in my browser as HTML files and read them side by side, though I don’t know if I can do this for the entire text.

I can’t get past the line from Sondheim’s Little Night Music — ‘There isn’t much blue in the Red and the Black’

My understanding is that having acquired knowledge and beliefs while growing up, our beliefs become “fixed” at adulthood, because there was an evolutionary advantage to this fixing. The alternative – constantly questioning everything – would have been inefficient and stressful and thus evolutionarily disadvantageous. So to question our beliefs is to some extent to fight nature, which is why it feels like hard work (in contrast to the comforting feeling of absorbing news that conforms to one’s existing world view). Apologies if this is all self-evident to readers.

I see the argument,and it does seem that many older people I’ve know find it hard to change, as the saying about old dogs and new tricks. But I’m generally leery of theories where human traits are attributed to evolution and thus to some form of genetics. It has a sort of just-so feel to me, and it’s hard to imagine what actual evidence we might have other than the fact that children are more open to being molded than adults. It would be fascinating if this were so, mostly because of the exceptions to the rule.

Should traits in other animals be attributed to evolutionary forces?

I’m pretty sure we are “just” very intelligent animals.

Thank you Ed, this is a theme that should be revisited often. I would add in ‘cognitive dissonance’ as well. We like our world to be consistent and coherent and as PeterS mentions it causes us stress to have it otherwise. I.e. I believe x but see y when I expected to see x and then we change our thoughts, actions, etc to relieve this tension.

The political ad with the person who was Republican and now votes Democrat is a good example – ‘i started to travel and talk to people…’

What he saw conflicted with what he thought therefore he needed to change something – go back home, change his opinions etc.

In a similar thought train…animals raised in environments without bonding or enrichment early on become very inflexible to any changes to their world later in their life…

Animalbehaviourandcognition.org

Vol 7 issue 3, and many others…

It does make you wonder if Leon Festinger read Peirce. I took a psych course while I was in law school which took up several theories related to how people can be persuaded, one of which was cognitive dissonance. I don’t recall anything useful about working against it from that course, which was disappointing.

Speaking of psychology, this article specifies some particular ways people get stuck in one track thinking. Now, somebody just needs to find a way to break the patterns and offer other possibilities.

“Mental health experts break down the 4 main psychological factors driving Trump supporters to cling to the president — despite his many failures”

…..

“How To Change Supporters’ Minds

“Based on our understanding of these psychological influences, each Trump supporter must be considered individually. Not all supporters are connected to Trump in the same way or for the same psychological reasons. For each Trump supporter, an individual assessment is required as to whether it might be best to address rebelliousness and chaos; shared irrationality; fear; and/or security and order. Rational arguments aimed at each of these categories, separately or in some combination, might be most effective.”

“Trump supporters are tied to him based on multiple and complex psychological principles and phenomena. To continue to respond to them as if they are psychotic or evil is a grave mistake and will not lead to change. Identifying the category or categories of psychological influence for each person can be a much more productive strategy.”

https://www.alternet.org/2020/09/mental-health-experts-break-down-the-4-main-psychological-factors-driving-trump-supporters-to-cling-to-the-president-despite-his-many-failures/amp/

Indeed.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an old book that really rings clear today:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/23

If you want to talk about someone observing the outside world and using self reflection to change the track of their life, it’s hard to think of a better example.

And it’s great to read, too. Douglass has a gripping, declarative style that is much more readable to modern audiences than something like Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He is also much more attuned to the psychological effects of enslavement on both Blacks and Whites than contemporaries like Stowe.

It obviously strikes down the myths behind nostalgia for the South, not simply about the supposedly benign nature of slavery, but about the severability of it from the broader aspects of Southern culture. And from the beginning it blew up the foundations of White Supremacy, both the crude form of Trump and the crazy pseudo intellectualism of Charles Murray and Andrew Sullivan.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X had a very strong impact on my teenage development.

Malcolm grew up in Michigan a highly intelligent successful student. His guidance counselor prejudicially and discouragingly recommended he learn a trade rather than entering a University or College. Discouraged he turned to crime ended up in prison and became a “Black Muslim”. When released from prison he quickly became a leader in Elijah Muhammad‘s “Black Muslim” movement. Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam movement, at that time believed that Islam was only for people of color. Malcolm filling his Islamic vows went on pilgrimage to Mecca. In Mecca he saw and met Islamic pilgrims from around the world from every race in the world. This affected him so strongly that Malcolm quit Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam movement and became a traditional Sunni Muslim. Spreading this message got him assassinated by Elijah Muhammad’ s men.

Have read some of the books listed. Now motivated for a re-read.

I think the Frankenstein meanings have been seriously derailed by the movie versions. I am unsure if any of the others have been made into moves and they probably shouldn’t unless by maybe someone like Spielberg. None the less, movie watching is in NO WAY a substitute for reading.

Ed, probably one of the most stimulating posts (to me) that you have done. Timely and spot on.

Pete

Thanks for letting me revisit Jane Austen. I took a semester class on novels of manners 55 plus years ago followed by another semester studying only Austen’s. I’ve reread them all but now is an especially good time to retreat into a couple of them again.

Two books that speak directly to 2020 just happen to be “science fiction” by Jack London:

The Scarlet Plague – about a pandemic which destroys society

and

The Iron Heel – about the rise of a totalitarian oligarchy in the USA

Let me add to that the novel ‘Earth Abides’ about a virus with a 99%+ kill rate — always seemed to me the most likely way civilization will end.

Not so old, but the topic is and it fits with Ed’s other recent work. The author of 2011’s Debt: The First 5000 Years, anthropologist David Graeber, died yesterday in Venice, Italy, of unknown causes. Trained at the University of Chicago, he was on the faculty of the London School of Economics.

I would place Graeber’s voice on the same end of the political spectrum as English geographer David Harvey – long associated with Johns Hopkins, and famous in in the US for his interpretation of Marx’s, Capital – and economist Michael Hudson. His latest book is …and Forgive Them Their Debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption from Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year (2018).

Graeber was also famous for having been denied tenure at Yale in 2005, although apparently having been on track for it. Graeber attributed the decision to his leftist political views and working class background (despite his having had scholarships to Phillips Andover and the University of Chicao). If true, it would have been consistent with the academy’s post-Watergate response to “too much democracy” in the 1960s and 1970s, exemplified in voices like William Sloane Coffin’s at Yale, Howard Zinn’s at Boston University, and C. Wright Mills’s at Columbia.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/sep/03/david-graeber-anthropologist-and-author-of-bullshit-jobs-dies-aged-59

This is terrible. I read Graeber’s excellent book: Debt: The First 5,000 Years at the recommendation of a friend; it’s really good. Yale sucks.

Another reason Yale might have denied David Graeber tenure: he actively supported Yale graduate student teachers’ efforts to form a union. That position would not win you points at any large American public or private university, which seem to regard their poorly paid and supervised graduate students as their grape pickers.

Yale, like its Ivy League peers, has an elaborate formal process for awarding tenure. But any institution that old and powerful runs on its informal networks. At the top is the board of trustees. When a majority of your board are from big bidness and venture capital, you begin to run your university according to their priorities. I don’t know the board’s composition in 2005, but today, after fifteen years of shouts for inclusiveness and diversity, out of 17 members (excluding ex officio members, CT’s governor and lt. governor), 11 are from big business, big medicine, and big capital.

https://twitter.com/aishaismad/status/1301519508415315976

Yale and Harvard are hedge funds loosely affiliated with colleges. If they gave one shit about education, they’d grow and take more of the actually brilliant students who don’t get in because legacies and football and upper middle class kids shoved ahead by parents who buy all the extras that the elites love. Fuck them.

Ed @355

Add Columbia to that list (as a real estate development corporation). 3rd largest land owner in NYC.

Progressive historian Howard Zinn was famously granted tenure at Boston University the afternoon before news came out about his participation at another BU sit-in against the Vietnam war. BU’s new arch-conservative neoliberal president, John Silber, was so infuriated over Zinn’s activism that he refused for decades to grant Zinn a pay raise. As it turns out, Silber was Yaley.

Another infamous tenure denial at Yale comes from 1996-98, several years before Graeber’s. Diplomatic historian Diane Kunz, author of Butter and Guns: America’s Cold War Economic Diplomacy (1997) was denied tenure, despite a glowing recommendation from her department.

The denial was the beginning of a two-year saga that did not change the result. Near its end, Kunz’s department and the University’s provost (senior academic administrator) asked for her tenure decision to be reconsidered – an almost unheard of request at Yale – based, in part, on the stellar reception for her Butter and Guns. Here’s the money quote: “It is very rare for the [secretive] Senior Appointments Committee to be questioned, and their vote [denying tenure] could have been a message to the provost’s office to mind its own business.” That’s academy-speak for fuck off, the old boy net has spoken.

https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-1998/the-kunz-tenure-decision-at-yale-utterly-inexplicable

The epilogue is no more heartening. Denied tenure at Yale, Kunz taught for three years at Columbia, then largely abandoned her once-promising career as a top diplomatic historian and returned to the law. Her degrees from Barnard, Oxford, and Yale became less important than her JD from Cornell. She left Columbia to practice and to teach, first at NYU’s law school, then Duke’s. Yea, fuck Yale.

Thank goodness for outsiders. Kay Ryan was excluded from the poetry club she tried to join in college. But she persisted in her career choice and went on to receive many awards, among them: being appointed US Poet Laureate (2008 – 2010) and receiving the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (2011.) Her work has been described as “haiku meets Groucho Marx.”

“Poets on Couches: Natalie Shapero reads Kay Ryan” (5 minutes long)

https://youtu.be/9KH5wn3O2Vw

I can scarcely express my shock at this news.

Stupifying.

He not only got denied tenure but was blackballed from American universities and despite his scholarship couldn’t get another job in US higher ed.

Heart of Darkness.

Conrad’s novel sustains it’s relevance a hundred years on. He doesn’t so much invite the reader but rather grabs one by the scruff and forces self-examination through a tale of horror wrapped in a socioeconomic citique. Impossible to read and remain unaffected.

Available free at the Gutenberg Project:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/219

Good factual background to read along with Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is Adam Hochschild’s, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Study of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1998).

A hundred years after Conrad’s fictionalized account, Hochschild’s well-researched history raised a storm of protest. But it – and Ludo de Witte’s, The Assassination of Lumumba – led to a long-delayed reckoning in Belgium (and in London and Washington), about Leopold’s legacy, admission of its complicity in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, and the continuing rape of the Congo.

If you like Conrad, Maya Jasanoff’s biography The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World is well worth reading.

There’s a review of The Dawn Watch here:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/21/books/review/dawn-watch-joseph-conrad-biography-maya-jasanoff.html

Now there’s a story that was an important part of a terrific movie …

For a discussion of the influence of The Theory of Moral Sentiments on Pride and Prejudice see:

Fricke, Christel. “The Challenges of Pride and Prejudice: Adam Smith and Jane Austen on Moral Education.” Revue Internationale de Philosophie No 269, no. 3 (November 24, 2014): 343–72. The paper includes extensive discussion in the footnotes as well references to other works that discuss the influence of Smith and others on Austen.

Thank you Ed. Pride and Prejudice is a favorite. Jane Austen was an insightful author creating insightful characters.

What is this ‘reading’ of which you speak ? Since Election night 2016, I haven’t been able to read for pleasure. My anxiety level has given me monkey mind and I find it hard to concentrate;my eyes are moving over the words but my brain is drifting off to the latest indignation. I am looking forward to January 21. After the hangover recovery.

That was a huge problem for me for weeks. Then I just turned out the news, quit reading Twitter, my social media, and binge-watched old movies for a couple of weeks, and read a couple of really dumb novels, beach reads, historical fiction, old favorites I knew really well, including Persuasion, that sort of thing. I listened to serious podcasts on stuff that interests me. It sort of worked. I managed a couple of short essays, and eventually a real book. I’m up to nearly two hours straight now. Survival is possible.

For me it’s been the virus – I’m just getting back into being able to read for an hour or so at a time.

(Just finished: “Keeper of the City” by Duane and Morwood. It’s the third book of a quartet, but the other three were written by other authors. Very good: swords, sorcery, romance. And no humans.)

I have the same problem — struggling to read with all the time in the world. One saving grace has been a movie club I started with 5 other couples. WE take turns choosing the films and do one a week discussing via zoom on Tuesday evenings. We get to ‘be’ with friends and talk about something besides the end of America and COVID — it has really helped. Watching the Tour de France now and that helps too.

Every year I read The Three Musketeers, 10 Years Later, Count of Monte Cristo, Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, just for pleasure and escapism. Then Les Miserables. This is less readable but Hugo is so urgent and intense that it draws you in. The scene from the barricade is from his own experience observing it, and it is visceral.

All these books are still very readable and I urge anyone who has avoided because of age to pick them up!

Whenever he was in bed with a cold or flu as an adult, my uncle reread Treasure Island. Better than Robert Newton’s, “Avast, mateys!”

If you like Alexandre Dumas, you might enjoy the Spanish writer Arturo Perez-Reverte. He’s written a series of historical novels chronicling the life and adventures of Captain Diego Alatriste y Tenorio, a soldier in the Spanish armies of Philip III and Philip IV during the time of the Thirty Years War. Captain Alatriste knows that the King is weak, that his court is corrupt and that the Spanish Hapsburgs are in decline, but he fights the King’s enemies nonetheless as a matter of professional honour and for the honour of Spain.

Perez-Reverte has written other novels with contemporary settings, including one called “The Dumas Club”, which as I recall sketchily has to do with the finding of an original manuscript of “The Three Musketeers”.

It is such a pleasure reading this blog.

Here is my favorite

“He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish.” Ernest Hemingway: The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

Note from Ed Walker: This is taken from The Counselor, The New York Law School JOurnal, published in January, 1896. The copyright is unclear, and if requested, we will take it down. The text, which I have put in blockquotes, is perhaps a transcript or other report of remarks made by Oliver Wendell Holmes at a dinner in June of the previous year. Thanks to commenter Epicurus for finding it. I found it online through my library.

If I might add something I recently read from a great man who has been tarnished by our frankly bigoted generation for not having the same values that we do, and also point out that there was a generation of intellectuals from 1880-1900 coming out of Harvard that had a healthy skepticism that, sadly, that school no longer lays claim to.

Just a suggestion, you may here from the site proprietor directly. I assume that’s a long quote. It’s helpful to readers if you indicate that more clearly, and cite the author and source material. Assure yourself that the work is out of copyright. If not, there’s a preference for shorter passages, to keep it within Fair Use guidelines.

Hear, hear.

It is a quote from Oliver Wendell Holmes. It can be found in The Counsellor: The New York Law School Law Journal, Volume 5.

Thanks. Since he died in 1935, much of Holmes’s work would be out of copyright, but not all of it. Works published in the NY Law School Journal would still be copyrighted. Good practice would be to keep to Fair Use guidelines.

Holmes wrote some very good

Holmes was himself an important figure in the development of American Pragmatism. He was a founding member of The Metaphyiscal Club, formed to debate these matters. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Metaphysical_Club Peirce was also a member. Louis Menand wrote a wonderful book, The Metaphysical Club, which I recommend to anyone interested n these matters. Menand is a brilliant writer, and no philosophy can be really understood apart from the history, the context in which it arose.

Thanks for the note and edit, Ed. The copyright for something first published in the US in 1896 will have expired.

At Play in the Fields of the Lord

Peter Matthiessen’s work is an adventure novel suffused with societal critiqe, Conradesque. If you require happy endings, this may not be the book you’re looking for.

Wonderfully, the film is brilliant on its own. Stunning cinematography, dream cast, a script that distills, sharpens and amplifies the characters and the themes, including the darkness. Movie magic.

The opening words from The Great Gatsby

“In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. Whenever you feel like criticising any one, he told me, just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” F Scott Fitzgerald: The Great Gatsby (1925)

In college, I took as an elective “The Modern Novel”. I haven’t been the same since.

Reading does allow you access to the mind of another; the author, and if they are deft, their imagos. Great post, Ed, and timely. So many good suggestions!

I’ll add a couple of less-popular nuts worth cracking: Faulkner’s ‘Absolom, Absolom’ and Gaddis’ ‘Carpenter’s Gothic’. Tough sledding at first, but once they catch you it’s off to the races.

And for pure junky joy, prime Chandler.

Raymond Chandler, yes! “She was a blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window.” “He was about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a wedding cake.” “He needed a shave. He would always need a shave.” “She walked towards me with a certain something I hadn’t often seen in bookstores.” “There was something sticky on the bedpost that the flies liked.” Just off the top of my head and probably not the exact wording, but those are some of the quotes that have stuck in my mind over the years from the Philip Marlowe novels.

Good topic for another thread: best juxtapositions. A list without Chandler would be as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food cake.

I recently read Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes were watching God.”

A catchy title and equally fast-paced, fast written book. She wrote the 193 page book in seven weeks in Haiti.

My favorite part is her depiction of a mighty hurricane.

“Through the screaming wind they heard things crashing and things hurtling and dashing with unbelievable velocity…. and the lake got madder and madder with only its dikes between them and him.”

And the language.

“Janie, Ah hope God may kill me, if Ah’m lyin”. Nobody else on earth kin hold uh candle tuh you, baby. You got de keys to de kingdom.’

Indeed. Janie Crawford, the main character, refuses as one writer puts it “to live in sorrow, bitterness, fear, or foolish romantic dreams.”

“It was the hour of twilight on a soft spring day towards the end of April in the year of Our Lord 1929, and George Webber leaned his elbows on the sill of his back window and looked out at what he could see of New York.” [You Can’t Go Home Again – Thomas Wolfe]” Kinda got my attention decades ago.

‘“A splendid afternoon to set out!,” said one of the friends who was seeing me off, peering at the rain and rolling up the window.’ [A Time of Gifts: On Foot to Constantinople: From the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube — Patrick Leigh Fermor]

An understated first line, but you probably picked up the book knowing a little bit of what it was about. When you return to that first line, after reading the book you appreciate it all the more. Worth reading if you haven’t, or worth re-reading. Paddy Fermor dropped (on foot) into one of those balance point moments of history, where the remnants of imperial Europe was tilting towards the pull of fascism.