I’ve written a bunch of times about an OLC memo Ron Wyden keeps pointing to, suggesting it should be declassified so we all can know what outrageous claims DOJ made about common commercial service agreements. Here’s my most complete summary from Caroline Krass’ confirmation process:

Ron Wyden raised a problematic OLC opinion he has mentioned in unclassified settings at least twice in the last year (he also wrote a letter to Eric Holder about it in summer 2012): once in a letter to John Brennan, where he described it as “an opinion that interprets common commercial service agreements [that] has direct relevance to ongoing congressional debates regarding cybersecurity legislation.” And then again in Questions for the Record in September.

Having been ignored by Eric Holder for at least a year and a half (probably closer to 3 years) on this front and apparently concerned about the memo as we continue to discuss legislation that pertains to cybersecurity, he used Krass’ confirmation hearing to get more details on why DOJ won’t withdraw the memo and what it would take to be withdrawn.

Wyden: The other matter I want to ask you about dealt with this matter of the OLC opinion, and we talked about this in the office as well. This is a particularly opinion in the Office of Legal Counsel I’ve been concerned about — I think the reasoning is inconsistent with the public’s understanding of the law and as I indicated I believe it needs to be withdrawn. As we talked about, you were familiar with it. And my first question — as I indicated I would ask — as a senior government attorney, would you rely on the legal reasoning contained in this opinion?

Krass: Senator, at your request I did review that opinion from 2003, and based on the age of the opinion and the fact that it addressed at the time what it described as an issue of first impression, as well as the evolving technology that that opinion was discussing, as well as the evolution of case law, I would not rely on that opinion if I were–

Wyden: I appreciate that, and again your candor is helpful, because we talked about this. So that’s encouraging. But I want to make sure nobody else ever relies on that particular opinion and I’m concerned that a different attorney could take a different view and argue that the opinion is still legally valid because it’s not been withdrawn. Now, we have tried to get Attorney General Holder to withdraw it, and I’m trying to figure out — he has not answered our letters — who at the Justice Department has the authority to withdraw the opinion. Do you currently have the authority to withdraw the opinion?

Krass: No I do not currently have that authority.

Wyden: Okay. Who does, at the Justice Department?

Krass: Well, for an OLC opinion to be withdrawn, on OLC’s own initiative or on the initiative of the Attorney General would be extremely unusual. That happens only in extraordinary circumstances. Normally what happens is if there is an opinion which has been given to a particular agency for example, if that agency would like OLC to reconsider the opinion or if another component of the executive branch who has been affected by the advice would like OLC to reconsider the opinion they will come to OLC and say, look, this is why we think you were wrong and why we believe the opinion should be corrected. And they will be doing that when they have a practical need for the opinion because of particular operational activities that they would like to conduct. I have been thinking about your question because I understand your serious concerns about this opinion, and one approach that seems possible to me is that you could ask for an assurance from the relevant elements of the Intelligence Community that they would not rely on the opinion. I can give you my assurance that if I were confirmed I would not rely on the opinion at the CIA.

Wyden: I appreciate that and you were very straightforward in saying that. What concerns me is unless the opinion is withdrawn, at some point somebody else might be tempted to reach the opposite conclusion. So, again, I appreciate the way you’ve handled a sensitive matter and I’m going to continue to prosecute the case for getting this opinion withdrawn.

The big piece of news here — from Krass, not Wyden — is that the opinion dates to 2003, which dates it to the transition period bridging Jay Bybee/John Yoo and Jack Goldsmith’s tenure at OLC, and also the period when the Bush Administration was running its illegal wiretap program under a series of dodgy OLC opinions. She also notes that it was a memo on first impression — something there was purportedly no law or prior opinion on — on new technology.

Back in November, ACLU sued to get that memo. The government recently moved for summary judgment based on the claim that a judge in DC rejected another ACLU effort to FOIA the document, which is a referral to ACLU’s 2006 FOIA lawsuit for documents underlying what was then called the “Terrorist Surveillance Program” and which we now know as Stellar Wind. Here’s the key passage of that argument.

The judgment in EPIC precludes the ACLU’s claim here. First, EPIC was an adjudication on the merits that involved the district court’s reviewing in camera the same document that is at issue in this litigation, and granting summary judgment to the government after finding that the government had properly asserted Exemptions One, Three, and Five – the same exemptions asserted here – to withhold the document. See Colborn Decl. ¶ 13; EPIC, 2014 WL 1279280, at *1. Second, the ACLU was a plaintiff in EPIC. Id. Finally, the claims asserted in this action were, or could have been, asserted in EPIC. The FOIA claim at issue in EPIC arose from a series of requests that effectively sought all OLC memoranda concerning surveillance by Executive Branch agencies directed at communications to or from U.S. citizens.2at See id. Even if the ACLU did not know that this specific memorandum was included among the documents reviewed in camera by the EPIC court, the ACLU had a full and fair opportunity to make any and all arguments in seeking disclosure of that document. Indeed, in EPIC, the government’s assertion of exemptions received the highest level of scrutiny available to a plaintiff in FOIA litigation—the district court issued its decision after reviewing the document in camera and determining that the government’s assertions of Exemptions One, Three, and Five were proper. Colborn Decl. ¶ 13. The ACLU’s claim in this lawsuit is therefore barred by claim preclusion.

2 One of the FOIA requests at issue in EPIC sought “[a]ll memoranda, legal opinions, directives or instructions from [DOJ departments] issued between September 11, 2001, and December 21, 2005, regarding the government’s legal authority for surveillance activity, wiretapping, eavesdropping, and other signals intelligence operations directed communications to or from U.S. citizens.” Elec. Privacy Information Ctr. v. Dep’t of Justice, 511 F. Supp. 2d 56, 63 (D.D.C. 2007).

Wyden just sent a letter to Loretta Lynch disputing some claim made in DOJ’s memorandum of law.

I encourage you to direct DOJ officials to comply with the pending FOIA request.

Additionally, I am greatly concerned that the DOJ’s March 7, 2016 memorandum of law contains a key assertion which is inaccurate. This assertion appears to be central to the DOJ’s legal arguments, and I would urge you to take action to ensure that this error is corrected.

I am enclosing a classified attachment which discusses this inaccurate assertion in more detail.

Here are some thoughts about what the key inaccurate assertion might be:

ACLU never had a chance to argue for this document as a cybersecurity document

Even the section I’ve included here pulls a bit of a fast one. It points to EPIC’s FOIA request (these requests got consolidated), which asked for OLC memos in generalized fashion, as proof that the plaintiffs in the earlier suit had had a chance to argue for this document.

But ACLU did not. They asked for “legal reviews of [TSP] and its legal rationale.” In other words, back in 2006 and back in 2014, ACLU was focused on Stellar Wind, not on cybersecurity spying (which Wyden has strongly suggested this memo implicates). So they should be able to make a bid for this OLC memo as something affecting domestic spying for a cybersecurity purpose.

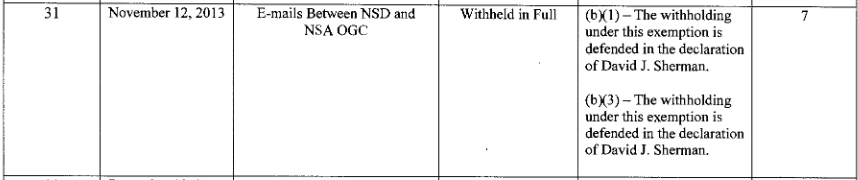

DOJ claimed only Wyden had commented publicly about the document, not Caroline Krass

DOJ makes a preemptive effort to discount the possibility that Ron Wyden’s repeated efforts to draw attention to this document might constitute new facts for the ACLU to point to to claim they should get the document.

Nor is there any evidence the memorandum has been expressly adopted as agency policy or publicly disclosed. Colborn Decl. ¶¶ 23-24. Although the ACLU’s complaint points to statements about the document by Senator Wyden, he is not an Executive Branch official, and his statements cannot effect any adoption or waiver

[snip]

The ACLU may argue that statements made by Senator Ron Wyden regarding the document, including in letters to the Attorney General, constitute new facts or changed circumstances. See Compl. ¶ 2 (“In letters sent to then–Attorney General Eric Holder, Senator Wyden suggested that the executive branch has relied on the Opinion in the past and cautioned that the OLC’s secret interpretation could be relied on in the future as a basis for policy.”). But such statements do not constitute new facts or changed circumstances material to the ACLU’s FOIA claim because they do not evince any change of the Executive Branch’s position vis-à-vis the document or otherwise affect its status under FOIA. See Drake, 291 F.3d at 66; Am. Civil Liberties Union, 321 F. Supp. 2d at 34. As the Senator is not an Executive Branch official, his statements about the document do not reflect the policy or position of any Executive Branch agency. See Brennan Center v. DOJ, 697 F.3d 184, 195, 206 (2d Cir. 2012); Nat’l Council of La Raza v. DOJ, 411 F.3d 350, 356-59 (2d Cir. 2005); infra at 11-12. Senator Wyden’s statements are simply not relevant to whether the document has been properly withheld under Exemptions One, Three, and Five, and do not undermine the applicability of any of those exemptions. Additionally, the Senator has made similar statements regarding the document at issue in letters sent during at least the last four years. Compl. ¶ 2. Thus, the Senator’s statements regarding the document are not new facts since they were available to Plaintiffs well before the district court ruled in EPIC.

That’s all well and good. But the entire discussion ignores that then Acting OLC head and current CIA General Counsel Caroline Krass commented more extensively on the memo than anyone ever has on December 17, 2013 (see my transcript above). This is a still-active memo, but the then acting OLC head said this about the memo in particular.

I have been thinking about your question because I understand your serious concerns about this opinion, and one approach that seems possible to me is that you could ask for an assurance from the relevant elements of the Intelligence Community that they would not rely on the opinion. I can give you my assurance that if I were confirmed I would not rely on the opinion at the CIA.

That seems to be new information from the Executive branch (albeit before the March 31, 2014, final judgment in that other suit).

I’d say this detail is the most likely possibility for DOJ’s inaccuracy, except that Krass’ comments are in the public domain, and have been been written about by other outlets. It wouldn’t seem that Wyden would need to identify this detail in secret.

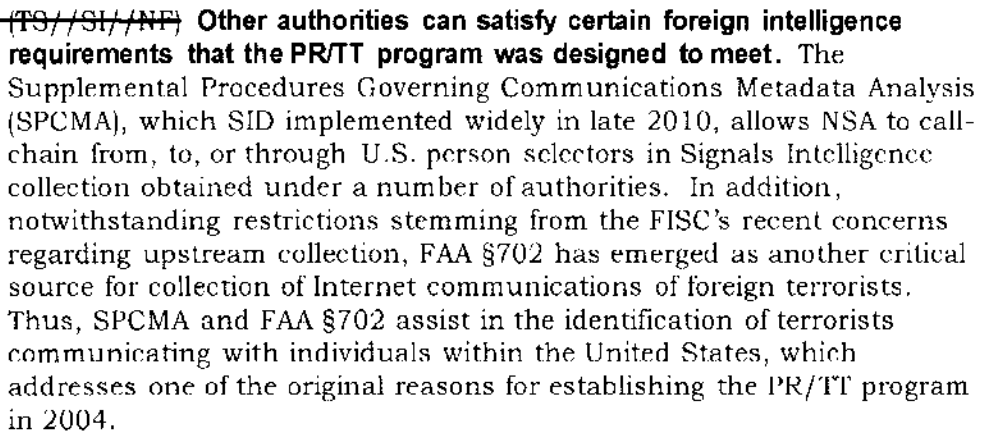

(I think it’s possible some of the newly declassified language in Stellar Wind materials may be relevant to, but I will have to return to that.)

The document may be a different document

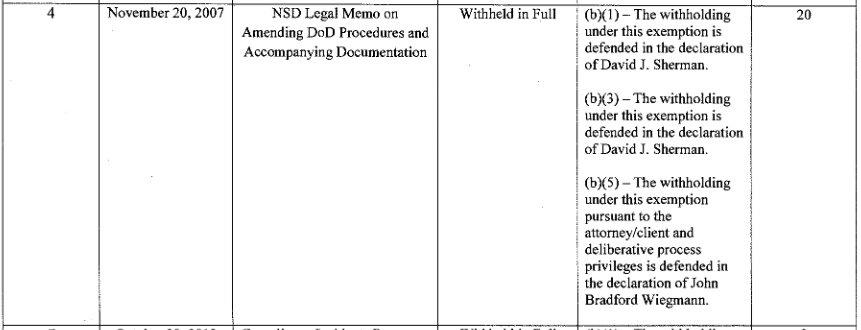

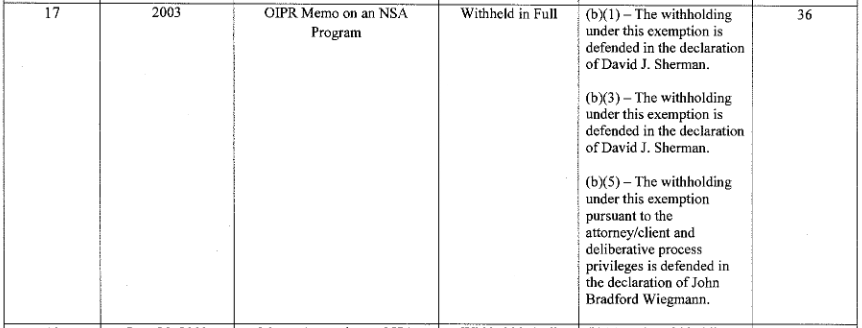

DOJ’s memo and the Paul Colborn declaration describe this as a March 30, 2003 memo written by John Yoo.

The withheld document is a 19-page OLC legal advice memorandum to the General Counsel of an executive branch agency, drafted at the request of the General Counsel, dated March 30, 2003 and signed by OLC Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo. The memorandum was written in response to confidential communications from an executive branch client soliciting legal advice from OLC attorneys. As with all such OLC legal advice memoranda, the document contains confidential client communications made for the purpose of seeking legal advice and predecisional legal advice from OLC attorneys transmitted to an executive branch client as part of government deliberative processes. In light of the fact that the document’s general subject matter is publicly known, the identity of the recipient agency is itself confidential client information protected by the attorney-client privilege.

But their claim that ACLU has already been denied this document under FOIA is based on the claim that this document is the same document as one identified in a Steven Bradbury declaration submitted in the Stellar Wind suit. Here’s how he described the document.

DAG 42 is a 19-page memorandum, dated May 30, 2003, from a Deputy Assistant Attorney General in OLC to the General Counsel of another Executive Branch agency. This document is withheld under FOIA Exemptions One, Three, and Five.

This may be an error (if so, Bradbury is probably correct, as March 30, 2003 was a Sunday), but a document dated March 30, 2003 cannot be the same document as one dated May 30, 2003. If it’s not a simple error in dates, it may suggest that the document the DC court reviewed was a later revision, perhaps one making less outrageous claims. Moreover, as I’ll show in my post on newly learned Stellar Wind information, the change in date (as well as the confirmation that Yoo wrote the memo) make the circumstances surrounding this memo far more interesting.

Update: In Ron Wyden’s amicus in this case, he made it clear the correct date is May 30, 2003.

The document may not have been properly classified

As noted, this is a March 2003 OLC memo written by John Yoo. That’s important not just because Yoo was freelancing on certain memos at the time. But more importantly, because a memo he completed just 16 days earlier violated all guidelines on classification. Here’s what former ISOO head Bill Leonard had to say about John Yoo’s March 14, 2003 torture memo.

The March 14, 2003, memorandum on interrogation of enemy combatants was written by DoJ’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) to the General Counsel of the DoD. By virtue of the memorandum’s classification markings, the American people were initially denied access to it. Only after the document was declassified were my fellow citizens and I able to review it for the first time. Upon doing so, I was profoundly disappointed because this memorandum represents one of the worst abuses of the classification process that I had seen during my career, including the past five years when I had the authority to access more classified information than almost any other person in the Executive branch. The memorandum is purely a legal analysis – it is not operational in nature. Its author was quoted as describing it as “near boilerplate.”! To learn that such a document was classified had the same effect on me as waking up one morning and learning that after all these years, there is a “secret” Article to the Constitution that the American people do not even know about.

[snip]

In this instance, the OLC memo did not contain the identity of the official who designated this information as classified in the first instance, even though this is a fundamental requirement of the President’s classification system. In addition, the memo contained neither declassification instructions nor a concise reason for classification, likewise basic requirements. Equally disturbing, the official who designated this memo as classified did not fulfill the clear requirement to indicate which portions are classified and which portions are unclassified, leading the reader to question whether this official truly believes a discussion of patently unclassified issues such as the President’s Commander-in-Chief authorities or a discussion of the applicability to enemy combatants of the Fifth or Eighth Amendment would cause identifiable harm to our national security. Furthermore, it is exceedingly irregular that this memorandum was declassified by DoD even though it was written, and presumably classified, by DoJ.

Given that Yoo broke all the rules of classification on March 14, it seems appropriate to question whether he broke all rules of classification on March 30, 16 days later, especially given some squirrelly language in the current declarations about the memo.

Here’s what Colborn has to say about the classification of this memo (which I find to be curious language), after having made a far more extensive withholding argument on a deliberative process basis.

OLC does not have original classification authority, but when it receives or makes use of classified information provided to it by its clients, OLC is required to mark and treat that information as derivatively classified to the same extent as its clients have identified such information as classified. Accordingly, all classified information in OLC’s possession or incorporated into its products has been classified by another agency or component with original classifying authority.

The document at issue in this case is marked as classified because it contains information OLC received from another agency that was marked as classified. OLC has also been informed by the relevant agency that information contained in the document is protected from disclosure under FOIA by statute.

As far as the memo of law, it relegates the discussion of the classified nature of this memo to a classified declaration by someone whose identity remains secret.

As explained in the classified declaration submitted for the Court’s ex parte, in camera review,1 this information is also classified and protected from disclosure by statute.

Remember, this memo is about some secret interpretation of common commercial service agreements. Wyden believes it should be “declassified and released to the public, so that anyone who is a party to one of these agreements can consider whether their agreement should be revised or modified.”

If this is something that affects average citizens relationships with service providers, it seems remarkable that it can, at the same time, be that secret (and remain in force). While Wyden certainly seems to treat the memo as classified, I’d really love to see whether it was, indeed, properly classified, or whether Yoo was just making stuff up again during a period when he is known to have secretly made stuff up.

In any case, given DOJ’s continued efforts to either withdraw or disclose this memo, I’d safe it’s safe to assume they’re still using it.