Existentialism and Ethics

Index to posts in this series. Please read this first; at least the section on de Beauvoir’s definition of ambiguity.

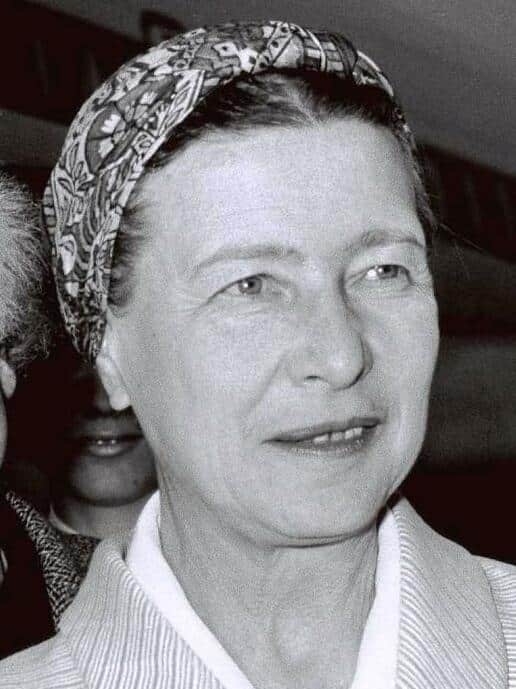

I’m on the road, and reading The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir. She was an Existentialist, as one would expect from a person in a long-term relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre. In Chapter 1 she gives an explanation of parts of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, the leading book on Existentialism. She distinguishes it from Stoicism and Marxism, but I won’t address that.

I think she opens with this because any systematic approach to ethics should begin with a statement of the writer’s understanding of human nature. De Beauvoir defines a specific ambiguity which I discussed in the introduction to this series. Her views are also informed by another ambiguity, the absurd. We want certainty. We want a foundation. But there isn’t one. We have to proceed, we have to live, without that certainty we want.

I read Being and Nothingness in College, but I didn’t, and don’t, care much for it. I agree with the Existentialists, including Sartre, that the universe is indifferent to its parts, from planets to mountains, flowers, insects, animals and human beings. I think there is no meaning to existence apart from our experience of it. Sartre explains that this lack of meaning gives us humans a radical degree of freedom, which we cannot avoid. Sartre’s explanation seemed to me to be wrapped up in silly little epigrams, like “Man’s being is not to be.” They did and do annoy me no end.

De Beauvoir gives a more sympathetic reading to Sartre’s tome, and for anyone interested, her explication in Chapter 1 of the wordy and needlessly obscure Sartre is worth reading. The point is to ground her discussion of ethics as a part of the human response to the meaninglessness of life and the freedom and responsibility it entails.

De Beauvoir discusses parts of Sartre’s book

Sartre’s statement that man is the being whose being is not to be begins with the notion of being. That seems to mean a fixed being, as an animal or a tree. People do not necessarily have a fixed nature. We might act like we do, we might aspire to have such a fixed being. But by nature, people live in a present filled with possibility, and want to participate in that possibility. We want to live in that wild freedom.

Freedom gives us the space in which we exist. We interact with others seeking to know them and in the process to know ourselves. We pursue our personal projects. We experience the savors and ugliness and all that come with existence. We want to be like gods in our existence, but this is an impossible and stupid goal.

I can not appropriate the snow field where I slide. It remains foreign, forbidden, but I take delight in this very effort toward an impossible possession. I experience it as a triumph, not as a defeat. This means that man, in his vain attempt to be God, makes himself exist as man, and if he is satisfied with this existence, he coincides exactly with himself. P 12-3.

By appropriate, I think she means merge myself, take possession of in my being, as a god would do. I think the idea of “coinciding” here means that we become fully human, our full selves, all we can be or aspire to be. We can and should aspire to be fully human, but we cannot be gods.

De Beauvoir says that for Sartre, one implication of embracing this freedom is that a fully human person will not accept any outside justification for their actions. People want to justify themselves, and we have to choose standards for justification we learn from others or create ourselves. Our ethics, then, come from the collective or from ourselves. We cannot have standards that emanate from some non-human place. I think this means that we must reject the absolute authority claimed by some religions.

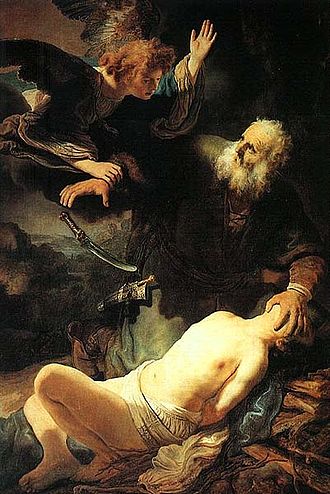

The second implication is that we bear responsibility for the results of our actions. We can’t claim that some external being is responsible for bad consequences. We act, we bear responsibility for the consequences. I think Fear and Trembling by the early Existentialist Sören Kierkegaard gives us a good example in the story of Abraham and Isaac. Abraham believes that the Almighty wants a human sacrifice, namely his only son Isaac. He acts on that belief. Whether he was right or wrong, he bears the consequences: a lost precious child, or a child tortured by the awareness that his father would kill him.

De Beauvoir says that we cannot escape our freedom, and we cannot avoid our responsibility. But we can simply refuse to will ourselves to exercise that freedom, out of “laziness, heedlessness, capriciousness, cowardice, [or] impatience” P. 25.

De Beauvoir says that responsibility only exists in our minds, in contemplation of the consequences of our actions. Feeling that responsibility happens over time, as those consequences become clear. This is a recognition that only grown-ups have these concerns.

The fact that we do not accept a justification outside ourselves is not a bar to an ethics.

An ethics of ambiguity will be one which will refuse to deny a priori that separate existants can, at the same time, be bound to each other, that their individual freedoms can forge laws valid for all. P. 18.

I think this is the source of ethics for de Beauvoir. We cooperate with other people to decide for ourselves what constitutes a justification for actions and projects. We choose to work together because we are part of the collective and our actions affects the collective directly. We share some of the burden of responsibility with others.

Discussion

1. I hope it’s clear which parts of this are mine and which are de Beauvoir’s. But it seems less important with this book. This book asks us to participate in the process of creating ethics, and therefore to think about the foundation of her ethics.

I think this book is useful because de Beauvoir is writing after horrors of the Third Reich and to a lesser extent those of Stalin were known and seen up close. That leads me to think her ethics addresses people of her day. Perhaps she intended to interrogate the behavior of the German people who enthusiastically welcomed and followed the Nazis. Certainly that’s an issue Camus addressed directly in The Plague.

Whether or not this was her purpose, we should ask ourselves what this foundation means for our understanding of the MAGAts, the people who enthusiastically follow Trump and his enablers and the filthy rich bastards who put him back in power.

2. I think we are formed by the collective in a deep way. For more, see my posts on The Evolution of Agency by Michael Tomasello, and other posts. It seems to me that this is the major contribution de Beauvoir makes to Existentialism. She describes Being and Nothingness as focused on the individual, who thrusts himself into the world. The foundation of her book is the ambiguity of being both an individual and being part of the collective.

I think we are formed by the people around us, parents, siblings, other relatives, friends, and institutions. I was raised Catholic, first in a traditional environment and then in a liberal environment. That has a profound influence on my sense of ethics,

I think we have to face our history directly and exercise our freedom to question what we were taught. We have to see ourselves clearly apart from the group in order to assess what we truly believe based on our own experience. Only then are we able to contribute something of our own to the ethics project.

3. I hate this translation: collective has an ugly Stalinist connotation.

4. De Beauvoir writes “… the ends toward which my transcendence thrusts itself …” on p. 14. The word thrust is used three times in Chapter 1, each time apparently quoting Sartre. In each case the connotation seems aggressively phallic. We don’t thrust ourselves into anything. I used the words “find” and “inject” above, trying to suggest that we will to act, but not in any aggressive sense.

I haven’t read The Second Sex, and I wonder if contemplation of this aspect of Being and Nothingness coupled with her sense of the importance of society had an influence on her thinking after writing this book.