Richard Burr Wants to Prevent Congress from Learning if CISA Is a Domestic Spying Bill

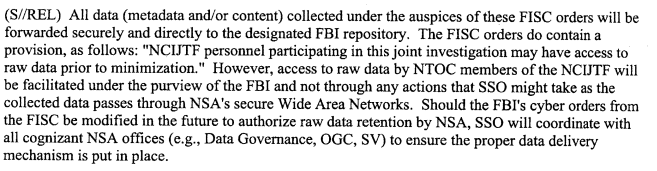

As I noted in my argument that CISA is designed to do what NSA and FBI wanted an upstream cybersecurity certificate to do, but couldn’t get FISA to approve, there’s almost no independent oversight of the new scheme. There are just IG reports — mostly assessing the efficacy of the information sharing and the protection of classified information shared with the private sector — and a PCLOB review. As I noted, history shows that even when both are well-intentioned and diligent, that doesn’t ensure they can demand fixes to abuses.

So I’m interested in what Richard Burr and Dianne Feinstein did with Jon Tester’s attempt to improve the oversight mandated in the bill.

The bill mandates three different kinds of biennial reports on the program: detailed IG Reports from all agencies to Congress, which will be unclassified with a classified appendix, a less detailed PCLOB report that will be unclassified with a classified appendix, and a less detailed unclassified IG summary of the first two. Note, this scheme already means that House members will have to go out of their way and ask nicely to get the classified appendices, because those are routinely shared only with the Intelligence Committee.

Tester had proposed adding a series of transparency measures to the first, more detailed IG Reports to obtain more information about the program. Last week, Burr and DiFi rolled some transparency procedures loosely resembling Tester’s into the Manager’s amendment — adding transparency to the base bill, but ensuring Tester’s stronger measures could not get a vote. I’ve placed the three versions of transparency provisions below, with italicized annotations, to show the original language, Tester’s proposed changes, and what Burr and DiFi adopted instead.

Comparing them reveals Burr and DiFi’s priorities — and what they want to hide about the implementation of the bill, even from Congress.

Prevent Congress from learning how often CISA data is used for law enforcement

Tester proposed a measure that would require reporting on how often CISA data gets used for law enforcement. There were two important aspects to his proposal: it required reporting not just on how often CISA data was used to prosecute someone, but also how often it was used to investigate them. That would require FBI to track lead sourcing in a way they currently refuse to. It would also create a record of investigative source that — in the unlikely even that a defendant actually got a judge to support demands for discovery on such things — would make it very difficult to use parallel construction to hide CISA sourced data.

In addition, Tester would have required some granularity to the reporting, splitting out fraud, espionage, and trade secrets from terrorism (see clauses VII and VIII). Effectively, this would have required FBI to report how often it uses data obtained pursuant to an anti-hacking law to prosecute crimes that involve the Internet that aren’t hacking; it would have required some measure of how much this is really about bypassing Title III warrant requirements.

Burr and DiFi replaced that with a count of how many prosecutions derived from CISA data. Not only does this not distinguish between hacking crimes (what this bill is supposed to be about) and crimes that use the Internet (what it is probably about), but it also would invite FBI to simply disappear this number, from both Congress and defendants, by using parallel construction to hide the CISA source of this data.

Prevent Congress from learning how often CISA sharing falls short of the current NSA minimization standard

Tester also asked for reporting (see clause V) on how often personal information or information identifying a specific person was shared when it was not “necessary to describe or mitigate a cybersecurity threat or security vulnerability.” The “necessary to describe or mitigate” is quite close to the standard NSA currently has to meet before it can share US person identities (the NSA can share that data if it’s necessary to understand the intelligence; though Tester’s amendment would apply to all people, not just US persons).

But Tester’s standard is different than the standard of sharing adopted by CISA. CISA only requires agencies to strip personal data if the agency if it is “not directly related to a cybersecurity threat.” Of course, any data collected with a cybersecurity threat — even victim data, including the data a hacker was trying to steal — is “related to” that threat.

Burr and DiFi changed Tester’s amendment by first adopting a form of a Wyden amendment requiring notice to people whose data got shared in ways not permitted by the bill (which implicitly adopts that “related to” standard), and then requiring reporting on how many people got notices, which will only come if the government affirmatively learns that a notice went out that such data wasn’t related but got shared anyway. Those notices are almost never going to happen. So the number will be close to zero, instead of the probably 10s of thousands, at least, that would have shown under Tester’s measure.

So in adopting this change, Burr and DiFi are hiding the fact that under CISA, US person data will get shared far more promiscuously than it would under the current NSA regime.

Prevent Congress from learning how well the privacy strips — at both private sector and government — are working

Tester also would have required the government to report how much person data got stripped by DHS (see clause IV). This would have measured how often private companies were handing over data that had personal data that probably should have been stripped. Combined with Tester’s proposed measure of how often data gets shared that’s not necessary to understanding the indicator, it would have shown at each stage of the data sharing how much personal data was getting shared.

Burr and DiFi stripped that entirely.

Prevent Congress from learning how often “defensive measures” cause damage

Tester would also have required reporting on how often defensive measures (the bill’s euphemism for countermeasures) cause known harm (see clause VI). This would have alerted Congress if one of the foreseeable harms from this bill — that “defensive measures” will cause damage to the Internet infrastructure or other companies — had taken place.

Burr and DiFi stripped that really critical measure.

Prevent Congress from learning whether companies are bypassing the preferred sharing method

Finally, Tester would have required reporting on how many indicators came in through DHS (clause I), how many came in through civilian agencies like FBI (clause II), and how many came in through military agencies, aka NSA (clause III). That would have provided a measure of how much data was getting shared in ways that might bypass what few privacy and oversight mechanisms this bill has.

Burr and DiFi replaced that with a measure solely of how many indicators get shared through DHS, which effectively sanctions alternative sharing.

That Burr and DiFi watered down Tester’s measures so much makes two things clear. First, they don’t want to count some of the things that will be most important to count to see whether corporations and agencies are abusing this bill. They don’t want to count measures that will reveal if this bill does harm.

Most importantly, though, they want to keep this information from Congress. This information would almost certainly not show up to us in unclassified form, it would just be shared with some members of Congress (and on the House side, just be shared with the Intelligence Committee unless someone asks nicely for it).

But Richard Burr and Dianne Feinstein want to ensure that Congress doesn’t get that information. Which would suggest they know the information would reveal things Congress might not approve of.