The Economic Myths Supporting The Existence Of Billionaires

This post contains links to other posts in this series.

I started this series by identifying the major causes of the problems we face with the MAGA movement spawned by Trump and glommed onto like leeches by fascists, Christian Dominionists, White Supremacists, anti-vaxxers, the grifters behind the manosphere and so many other creeps and perverts. In this post I offer a thought on dealing with the filthy rich.

My suggestion is to unlearn the stupid ideas about capitalism that dominate our education system and our political discourse. Replace them with something approximating reality.

Background

Since the beginning of this country, the filthy rich have hated democracy, arguing that the masses would use the power of government to seize their wealth and reduce their power. The filthy rich of the day hated FDR, and worked to destroy his legacy.

As part of that campaign, they linked capitalism to democracy, so that if you didn’t support their views of capitalism, if you even asked questions about it, you were a commie, an enemy of democracy. They became vocal advocates of the simple-minded economics we were all taught in high school and/or college, and spent massive sums to eradicate all alternatives. My first econ course was taught out of Samuelson on Economics, editions of which are still standard in colleges.

I’ve written extensively about this here at Emptywheel. Some of those posts don’t hold up well, but all of them raise substantial questions about the economic theories underlying neoliberal capitalism. Search the site for Jevons, for example. The ideas that underlie marginal utility spring from the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham. I hope we’ve all outgrown that.

Of course, there may be some value in the simple models of Econ 101. But all of it is open to question, and all of it requires more justification than “Mankiw said so in his textbook”.

Examples

1. Trickle-down. Surely there is no one left who seriously believes that trickle-down theory has any merit other than as a laugh line. But versions of it are everywhere. Here’s a Bluesky post by Mark Cuban, one of the filthy rich.

Want to use rich people like me to your advantage? Incent us to help those who need it the most. Lower corp taxes for comps that pay a min of $25 per hour. Lower corp taxes if employees get stock at the same pct as the CEO. Bottom up incentives work. Dems never innovate. They bitch

This is a form of trickle-down. Give the filthy rich a tax cut, and the benefits will trickle down to someone. Only, of course, that’s not how things work. Corporations won’t do that unless the benefits outweigh the costs. The tax cuts have to be at least equal to the cost of raising wages. Companies that already pay close to $25 per hour will get a tax cut greater than the cost of raising wages. Companies that pay substantially less won’t raise wages, meaning the worst-paying jobs in the worst industries won’t benefit.

The Chicago Bears don’t like Soldier Field, and want the city to build them a new stadium. They tell us we Chicagoans will benefit from having a new stadium so we should pay for it to encourage them to build it. Well, the Bears owners benefit from being in our city, which is a much greater value. What do they think the TV market looks like in Omaha? The owners are rich. If they were capitalists, they’d build it themselves.

Wages

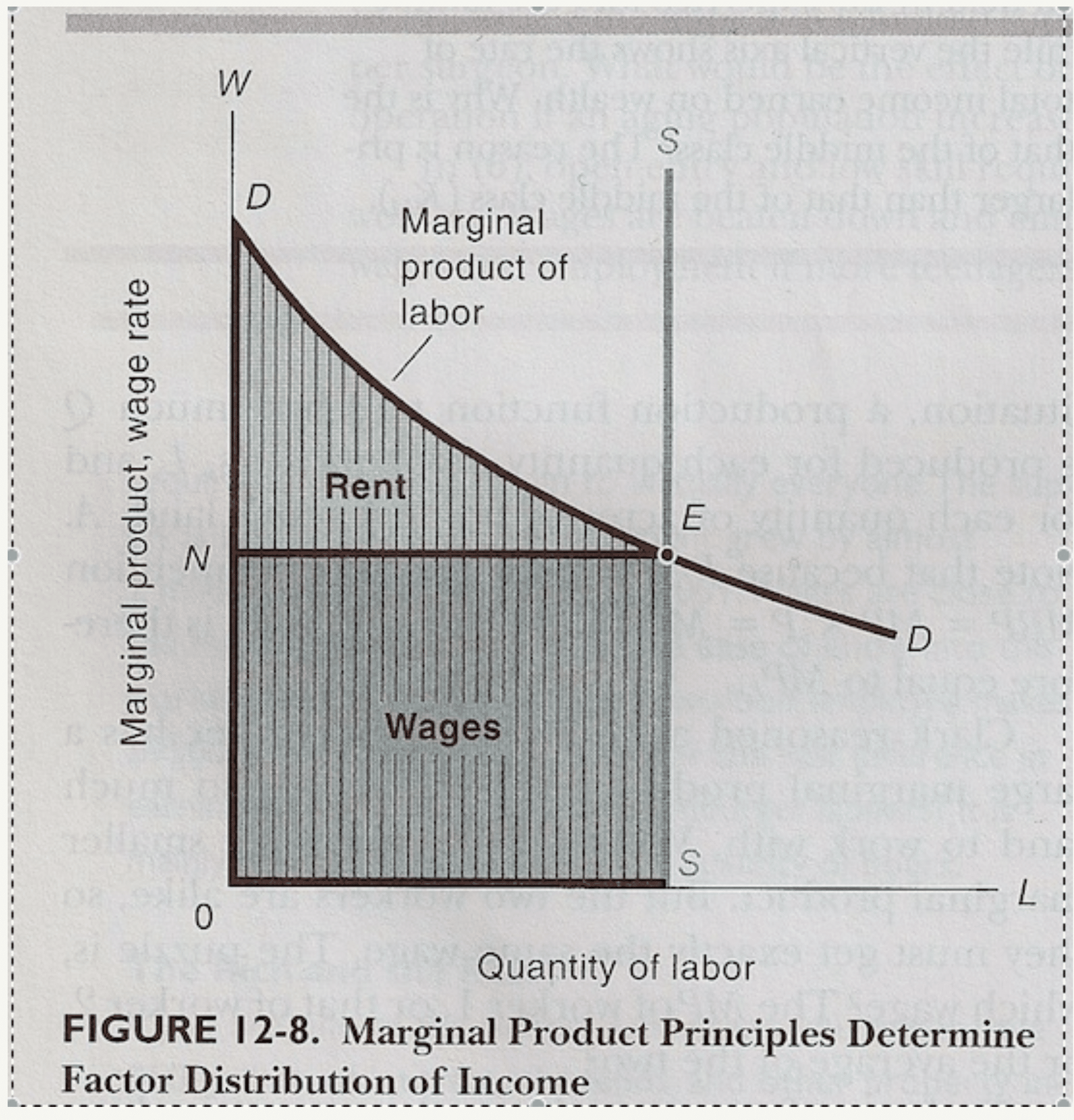

I wrote a post on the justification for allocation of the profits from business activities. Please read it. It’s a good example of the kind of nonsense smuggled into economic analysis using simple-minded models. The argument from the standard economics text begins by assuming we live in a competitive capitalist system. We don’t. The model fails at the outset.

But worse, it hides the reality that everything in the real world is set up by people who already have power and wealth. Why would such a system benefit anyone other than the people who set it up, except by accident? Consider the enclosure laws which drove people into “dark Satanic Mills”, as William Blake called them in his short 1810 poem Jerusalem.

The Econ 101 model hides the fact that the allocation of income is a political issue, and that workers can and should fight for a bigger share than the mingey allocation authorized by John Bates Clark and his Natural Laws.

Land

Capitalism is built on ownership of private property. Much of English history is bound up in the struggle of aristocrats to hold onto their property against the power of the monarch. Here’s John Locke in his Second Treatise on Government, Chapter V, § 32:

But the chief matter of property being now not the fruits of the earth, and the beasts that subsist on it, but the earth itself; as that which takes in and carries with it all the rest; I think it is plain, that property in that too is acquired as the former. As much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does, as it were, inclose it from the common. Nor will it invalidate his right, to say every body else has an equal title to it; and therefore he cannot appropriate, he cannot inclose, without the consent of all his fellow-commoners, all mankind.

Is it that plain? I can see why the usufructs of the land collected by this guy should be his, whether he raised them himself or merely found them. But what is the source of his claim to the earth itself? And why does it survive him and go to his heirs? And why is he allowed to sell it and keep all the money? Locke doesn’t say.

And indeed, it seems plain to me that these questions are obscured by Locke’s assertions. Doubtless it was true of the monarch, because the monarch had armed troops to back him up. But why should it be true now? And whatever the justifications might be, are there no limits?

Here’s one perspective. Our ancestors drove the Native Americans off the land and claimed much of it for the government. The railroads wanted incentives to build out their systems (see trickle-down), so the government gave them a big chunk of the land. Then the railroads sold it. A public resource was turned into cash by the rich. How would Locke explain that? What would be today’s equivalent? Giving leases to oil companies to drill on our national forests? Is that cool?

Conclusion

These are three examples of the simple-minded capitalism that infests our minds. From this kind of tripe, we get ideas about intellectual property in gene sequences, and patents on computer code. Why though? We did it without thinking.

Now it’s time for those of us who can to start thinking about these foundational idea. They were given to us by people like Adam Smith or William Stanley Jevons, as are all our ideas. And mostly they no longer describe reality. When they’re gone, replaced by something better, how can the filthy rich justify their wealth and power?