I Con the Record Transparency Bingo (2): The Inexplicable Drop in PRTT Numbers

As noted in this post, I’m going to start my review of the new I Con the Record Transparency Report by addressing misconceptions I’m seeing; then I’ll do a complete working thread. In this post, I’m going to address what appears to be a drop in FISA PRTT searches.

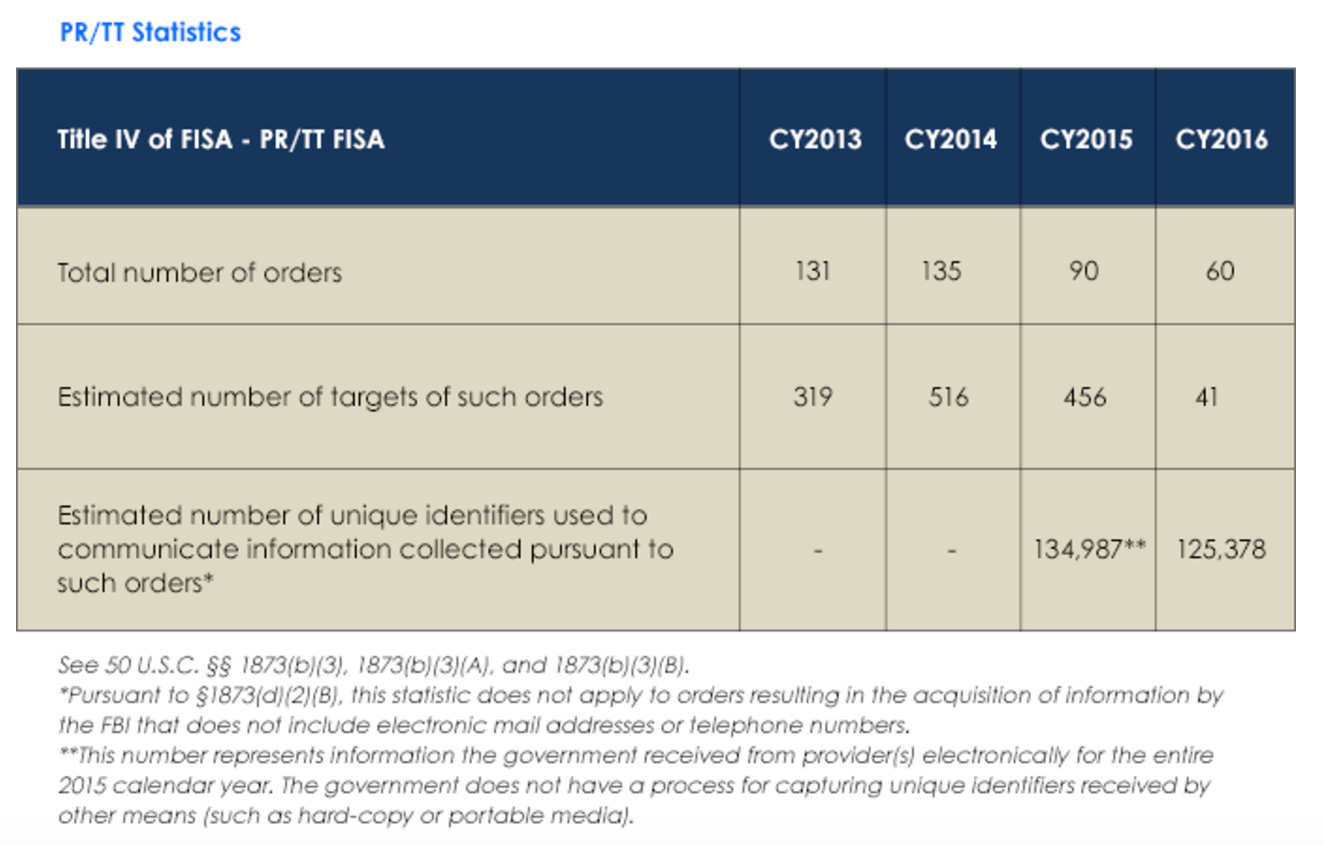

The report does, indeed, show a drop, both in total orders (from 131 to 60 over the last 4 years) and an even bigger drop in targets (from 319 to 41).

Some had speculated that this drop arises from DOJ’s September 2015 loophole-ridden policy guidance on Stingrays, requiring a warrant for prospective Stingrays. But that policy should have already in place on the FISC side (because FISC, on some issues, adopts the highest standard when jurisdictions start to deal with these issues). In March 2014, DOJ told Ron Wyden that it “elected” to use full content warrants for prospective location information (though as always with these things, there was plenty of room for squish, including on public safety usage).

As to the drop in targets: it’s unclear how meaningful that is for two reasons.

First, the ultimate number of unique identifiers collected has not gone down dramatically from last year.

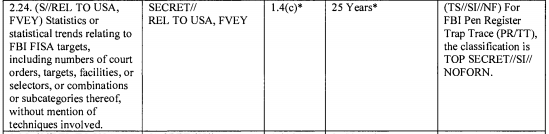

Last year, the 134, 987 identifiers represented 243 identifiers collected per target, or 1,500 per order. This year, the 125,378 identifiers represents a whopping 3,078 per target or 3,756 per order. So it’s appears that each order is just sucking up more records.

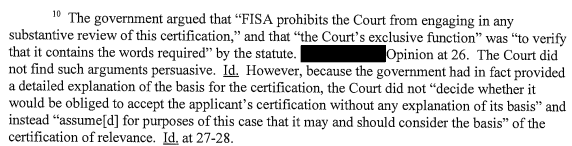

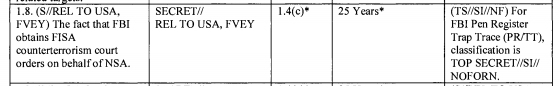

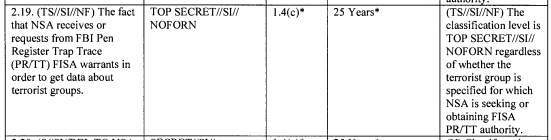

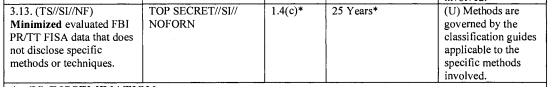

But something else may be going on here. As I pointed out consistently though debates about these transparency guidelines, the law ultimately excluded everything we knew to include big numbers. And the law excludes from PRTT identifier reporting any FBI obtained identifier that is not a phone number or email address, as well as anything delivered in hard copy or portable media.

For all we know, the number of unique identifiers implicated last year is 320 million, or billions, but measuring IP addresses or something else. [Update: Reminder that the FBI used a criminal PRTT in the Kelihos botnet case to obtain the IP addresses of up to 100,000 infected computers, but that’s the kind of thing they might use a FISA PRTT for.]

Alternately, it’s possible some portion of what had been done with PRTTs in 2015 moved to some other authority in 2016. A better candidate for that than Stingrays would be CISA voluntary compliance on things like data flow.

One final note. Unless I misunderstand the count, we’re still missing one amicus brief appointment from 2015. The FISC report from that year (covering just 7 months) said there were four appointments across three amici.

During the reporting period, on four occasions individuals were appointed to serve as amicus curiae under 50 U.S.C. § 1803(i). The names of the three individuals appointed to serve as amicus curiae are as follows: Preston Burton, Kenneth T. Cuccinelli II (with Freedom Works), and Amy Jeffress. All four appointments in 2015 were made pursuant to § 1803(i)(2)(B). Five findings were made that an amicus curiae appointment was not appropriate under 50 U.S.C. § 1803(i)(2)(A) (however, in three of those five instances, the court appointed an amicus curiae under 50 U.S.C. § 1803(i)(2)(B) in the same matter).

Burton dealt with the resolution of the Section 215 phone data, Ken Cuccinelli dealt with FreedomWork’s challenge to the way USAF extended the phone dragnet, and Amy Jeffress dealt with the Section 702 certificates.

That leaves one appointment unaccounted for (and I’d bet money Jeffress dealt with that too). On June 18, 2015, FISC decided not to use an amicus with an individual PRTT order that was a novel interpretation of what counted as a selection term under USAF. It chose not to use an amicus because the PRTT had already expired and because there were no amici identified at that point to preside. If that issue recurred for a more permanent PRTT later in the year, it may have affected how ODNI counted PRTTs (or the still-hidden amicus use may be for another kind of individual order).

All of which is to say, the government appears to be obtaining fewer PRTT orders over the last two years. But it’s not yet clear whether that has any effect on privacy.