Criminal Sexual Assault: No Means NO Burden Shifting

Late last night here, early this morning where many of you are, I saw an article pop up on the New York Times website by Judith Shulevitz on “Regulating Sex”. The title seemed benign enough, but thanks to my friend Scott Greenfield, and his blog Simple Justice, Ms. Shulevitz has been on my radar for a while. So I sent the article (which is worth a read) to Scott knowing he would likely pounce on it when he got up.

Late last night here, early this morning where many of you are, I saw an article pop up on the New York Times website by Judith Shulevitz on “Regulating Sex”. The title seemed benign enough, but thanks to my friend Scott Greenfield, and his blog Simple Justice, Ms. Shulevitz has been on my radar for a while. So I sent the article (which is worth a read) to Scott knowing he would likely pounce on it when he got up.

And Scott did just that, in a post called “With Friends Like These”, while I was still comfortably tucked in:

A lot of people sent me a link to Judith Shulevitz’s New York Times op-ed, Regulating Sex. As any regular SJ reader knows, there is nothing in there that hasn’t been discussed here, sometimes long ago, at far greater depth. But Shulevitz is against the affirmative consent trend, which she calls a “doctrine,” so it’s all good, right?

What Shulevitz accomplishes is a very well written, easily digestible, version of the problem that serves to alert the general public, those unaware of law, the issues of gender and sexual politics, the litany of excuses that have framed the debate and the seriousness of its implications, to the existence of this deeply problematic trend. She notes that one of its primary ALI proponents, NYU lawprof Stephen J. Schulhofer, calls the case for affirmative consent “compelling.” She neglects to note this is a meaningless word in the discussion. Still, it’s in there.

On the one hand, I think Scott is right that there is really nothing all that new here in the bigger picture, and, really he is right that Ms. Shulevitz is far from a goat, even if a little nebulous and wishy washy.

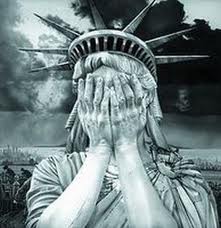

No, what struck me like a hammer was the ease with which academics like Georgetown’s Abbe Smith and NYU professor Stephen J. Schulhofer, not to mention the truly formidable American Law Institute (ALI) are propagating the idea of alteration of criminal sexual assault law. In short, are willing to put lip gloss on the pig of shifting the burden of proof on a major felony crime of moral turpitude.

And it is an outrageous and destructive concession. This is not a slippery slope, it is a black ice downhill. You might as well be rewriting the American ethos to say “Well, no, all men and women are not created equal”. In criminal law, that is the kind of foundation being attacked here.

Scott did not really hit on this in his main post, but in a reply comment to some poor soul that weighed in with the old trope of “gee, it really is not too much to give” kind of naive rhetoric, Mr. Greenfield hit the true mark:

The reason I (and, I guess, others) haven’t spent a lot of time and energy providing concrete examples is because it’s so obvious. Apparently, not to everyone. So here’s the shift:

Accuser alleges rape because of lack of consent, saying: “He touched me without my consent.” That’s it. Case proven. Nothing more is required and, in the absence of a viable defense, the accused loses.

Now, it’s up to the accused student to prove, by a preponderance of the evidence (which means more than 50%) that there was consent. There was consent at every point in time. There was clear and unambiguous consent. And most importantly, that the accused’s assertion of consent somehow is proven to be more credible than the accuser’s assertion of lack of consent.

Let’s assume the accuser says “I did not consent,” and the accused says, “you did consent.” The two allegations are equally credible. The accused loses, because the accuser’s assertion is sufficient to establish the offense, and the burden then shifts to the accused, whose defense fails to suffice as being more credible than the accusation.

Mind you, under American jurisprudence, this shifting compels the accused to prove innocence, which is something our jurisprudence would not otherwise require, merely upon the fact of an accusation, or be peremptorily “convicted.”

Is that sufficiently concrete for you?

Yeah, and do you want that star chamber logic in not just public university settings, but embedded with a solid foothold in common criminal law? Because those are the stakes. Constitutional law, criminal law, and criminal procedure are not vehicles for feel good patina on general social ills and outrages de jour, in fact they are instead designed, and must be, a bulwark against exactly those people who would claim the former mantle.

First they came for the Fourth and Fifth Amendments, and you poo poohed the cries from criminal defense lawyers, going back to at least the mid-80’s, about the dangerous slippery slope that was being germinated. Whether the results have touched you, or your greater “family”, yet or not, it is pretty hard to objectively look at today’s posture and not admit the “slippery slope” criers thirty years ago were right. Of course they were.

People operating from wholly, or mostly, within the criminal justice system, whether as lawyer or client/family, just have a different, and more immediate, perspective. A position rarely understood without having tangible skin in the game.

Maybe listen this time. The battle over racial and sexual equality is far from over, but it is well underway intellectually, and headed in a better direction. It gets better. So, make it better in criminal justice too, do not let it be the destructive war pit morality betterment in the US falls in to.

look to the old bastardy laws for establishing burden of proof

you need the act of sex to be observed by numerous neutral parties, with talk about the act beforehand to be done with close friends.

not comfortable with it?

that’s how burden of proof works.

Huh???

Exactly.

The Times nebulous and wishy washy? Only one of its casual or avid reader could think so. :-) Thanks for catching another of the Times’ attempts to keep the Westchester set warm and dry on a Sunday morning.

One question. In a criminal case, if the accused and accuser’s testimony is equally credible, and there’s no other evidence, how can the case be proven beyond a reasonable doubt?

Short answer: it can’t. If both stories are equally credible, and barring anything other than the stories, then the defendant is supposed to get a walk.

.

I cannot say – I long ago lost count – of the number of times I’ve heard some media idiot talk about “giving the accused a chance to prove his innocence.” The accused doesn’t have to prove a damned thing. Unfortunately, this bullshit has been repeated so many times by so many idiots (and malevolent cops and prosecutors) that it’s been accepted as “true”.

I have two words for those who think this is OK:

Scottsboro Boys.

Want another two words?

Emmitt Till.

As Shulevitz and Schulhofer know, the legal system rarely has a light touch on the vast majority of those caught up in it. Law enforcement is also often heavily politicized. Bankers and CEO’s and local robber barons and their children may have too much juice to prosecute; most other people haven’t the resources to turn their nominal legal rights into practical ones. Shulevitz understates that disparate treatment.

This isn’t a permissive country. Prosecutors and media salivate over transgressions by the uninvited, such as racial or sexual minorities or nonconformists opposed to locally popular people, stereotypes or institutions.

Overly inclusive definitions that criminalize “touching” and shifting burdens of proof to the accused could easily and predictably have catastrophic consequences, even in states that have higher standards than Texas justice.

Right. This is why I scream at SCOTUS nominees that, like Kagan and all, really but Sotomayor, have never been in trial courts in anger. The criminal justice system is a very imperfect, but living and breathing thing, and you don’t know it if you have not been there. There is certainly bad, but there is good too; it is a weird mix, but it works, on the whole better than most of the uninformed think.

Same for the general trial court system as a whole. Most of the people whining the loudest have the least experience with it. It works far better, and more often, than you know.

look, in our society the big fight has always, ALWAYS, been to keep the state – executive, legislature, or judiciary in the american case – from unfairly seizing and using power over individual citizens of the state.

where the state has rendered a citizen “the accused”, we have a set of rules for determining whether or not the state may take from that citizen, or authorize others to take from that citizen, life, liberty, or property. we call these rules “rules of civil and criminal procedure”. these rules are onerous enough as it is is, and made far worse than their content would suggest by this society’s current excessive leniency toward prosecutors, their intolerable abuse of the grand jury process (for and against), and the credulousness of its judges.

no accused, whether accused of whistleblowing, murder ssy by police), philandering, “hate crime”, or rape should have additional special rules implemented that prevents her/him from receiving the greatest possible leniency the rules of procedure allow.

we cannot permit special laws and special rules of procedure to be applied by the state to special categories of a generally criminal activity. that is precisely the prosecutorial abuse that has led to the imprisonment of american muslim preachers on the state’s pretextual assertion of “material support for terrorism”, just to provide a somewhat neutral example in the context of rape accusations.

i also need to add that human adult emotional and sexual behavior, particularly when combined with mutual use of drugs such as ethlyl alchohol, is a rat’s nest of changing and sometimes conflicting emotions.

it is especially important to keep in mind that we are discovering that our governments (state even more so than federal) have imprisoned citizens who are unambiguously not guilty of the crime for which their liberty was taken from them by supposed trustworthy deputies of the state.

a notorious example, recently in the news again, is the fbi’s hair analysis laboratory. thousands of cases probably should be thrown out – but probably will not be because we coddle dishonest fbi police and prosecutors.

another example is the conduct of the chicago police in torturing “suspects” to confess.

a third is the conduct of the notorious new york detective scarcella and his partner.

a more general example involves the advance of the science of genetics to the point where tiny dots of dna can be analyzed to identify an individual. but fairly ? that may not be the case.

i’ve already mentioned summary judgement by hundreds of police officers – on a yearly basis.

The same notion of “proving innocence” is embedded in discussions of the supposed “2-8%” false accusation rate. The number comes from studies that look at police investigations of rape. They find a 2-10% rate of cases that the police think are proven false (mostly stranger rape cases where the crime definitely didn’t happen), a 40-60% rate of cases that the police think don’t have enough evidence to charge the crime but aren’t definitely false, and the rest are cases that are charged. It’s assuming the consequent to claim that all the “not enough evidence to charge” cases are clearly true. (It’s also quite a lot to assume that the police are perfect and unbiased in their judgment.) I don’t know how many of those cases are true, but we have a high standard of proof for a reason.

We wouldn’t stand for this for any other crime (well, I’d like to think that, but unfortunately for lots of crimes we do, including having too much cash on you).