The Intelligence Community’s Swiss Cheese Preemptive 702 Unmasking Reports: Now with Twice the Holes!

Because a white man still liked by some members of Congress had FISA-collected conversations leaked to the press, Republicans who used to applaud surveillance started to show some more concerns about it this year. That has been making reauthorization of Section 702 unexpectedly challenging. Both the HJC and SJC bills reauthorizing the law include new reporting requirements, which include mandates to provide real numbers for how many Americans get unmasked in FISA reports. There’s no such requirement on the SSCI bill.

Instead, explicitly in response to concerns raised in SSCI’s June 7 hearing on 702 reauthorization (even though the concern was also raised earlier in HJC and SJC hearings), I Con the Record has released an ODNI report on disseminations under FISA, a report it bills as “document[ing] the rigorous and multi-layered framework that safeguards the privacy of U.S. person information in FISA disseminations.”

The report largely restates language that is available in the law or declassified targeting and minimization procedures, though there are a few tidbits worth noting. Nevertheless, the report falls far short of what the SJC and HJC bills lay out, which is a specific count and explanation of the unmasking that happens (though NSA, in carrying out a review of a month’s worth of serialized reports, examining out their treatment of masking, does model what HJC and SJC would request).

The report consists of the DNI report with separate agency reports. I’ll deal with the latter first, then return to the DNI report.

The NSA report starts by narrowing the scope of the dissemination it will cover significantly in two ways.

This report examines the procedures and practices used by the National Security Agency (NSA) to protect U.S. person information when producing and disseminating serialized intelligence reports derived from signals intelligence (SIGINT) acquired pursuant to Title I and Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, as amended (FISA). 1

1This report is limited to an examination of the procedures and practices used to protect FISA-acquired U.S. person information disseminated in serialized intelligence reports. This report does not examine other means of dissemination. For purposes of this report, the term “dissemination” should be interpreted as a reference to serialized intelligence reporting, unless otherwise indicated.

First, it treats just Title I and Section 702. That leaves out at least two other known collection techniques of content (to say nothing of metadata) under FISA: Title III (FBI probably does almost all of this, though it might be accomplished via hacking) and Section 704/705b targeting Americans overseas (which has been a significant problem of late).

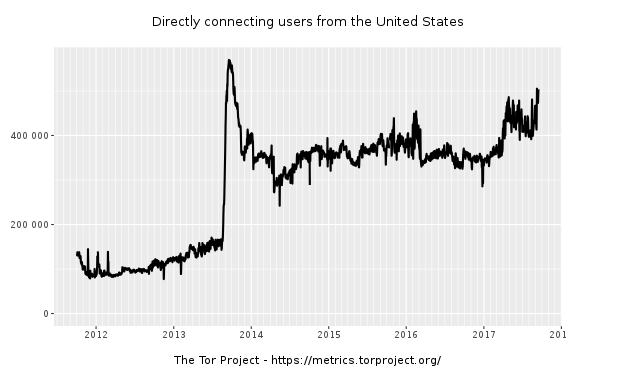

More importantly, by limiting the scope to serialized reports, NSA’s privacy officer completely ignores the two most problematic means of disseminating US person data: by collecting it off Tor and other location obscured nodes and then deeming it evidence of a crime that can be disseminated in raw form to FBI, and by handing raw data to the FBI (and, to a lesser extent, CIA and NCTC).

As the report turns to whether NSA’s procedures meet Fair Information Practice Principles, then, the exclusion of these four categories of data permit the report to make claims that would be unsustainable if those data practices were included in the scope of the report.

The principle of Data Minimization states that organizations should only collect PII that is directly relevant and necessary to accomplish the specified purpose. The steps taken from the outset of the SIGINT production process to determine what U.S. person information can and should be disseminated directly demonstrate how this principle is met, as do NSA’s procedures and documentation requirements for the proactive and post-publication release of U.S. identities in disseminated SIGINT.

The principle of Use Limitation provides that organizations should use PII solely for the purposes specified in the notice. In other words, the sharing of PII should be for a purpose compatible with the purpose for which it was collected. NSA’s SIGINT production process directly reflects this principle.

[snip]

The principle of Accountability and Auditing states that organization should be accountable for complying with these principles, providing training to all employees and contractors who use personally identifiable information, auditing the actual use of personally identifiable information to demonstrate compliance with these principles and all applicable privacy protections.

For example, the collection of US person data off a Tor node is not relevant to the specified purpose (nor are the criminal categories under which NSA will pass on data). That’s true, too, of Use Limitation: the government is collecting domestic child porn information in the name of foreign intelligence, and the government is doing back door searches of raw 702 data for any matter of purpose. Finally, we know that the government has had auditing problems, particularly with 704/705b. Is that why they didn’t include it in the review, because they knew it would fail the auditing requirement?

CIA’s report is not as problematic as NSA’s one, but it does have some interesting tidbits. For example, because it mostly disseminates US person information for what it calls tactical purposes and to a limited audience, it rarely masks US person identities.

More specifically, unlike general “strategic” information regarding broad foreign intelligence threats, CIA’s disseminations of information concerning U.S. persons were “tactical” insofar as they were very often in response to requests from another U.S. intelligence agency for counterterrorism information regarding a specific individual, or in relation to a specific national security threat actor or potential or actual victim of a national security threat.

Relatedly, because these disseminations were generally for narrow purposes and sent to a limited number of recipients, the replacement of a U.S. person identity with a generic term (e.g., “named U.S. person,” sometimes colloquially referred to as “masking”) was rare, due to the need to retain the U.S. person identity in order to understand the foreign intelligence information by this limited audience.

CIA, like NSA, has its own unique definition of “dissemination:” That which gets shared outside the agency.

Information shared outside of CIA is considered a dissemination, and is required to occur in accordance with approved authorities, policies, and procedures.

Much later, dissemination is described as retaining information outside of an access-controlled system, which suggests fairly broad access to the databases that include such information.

Prior to dissemination of any information identifying, or even concerning, a U.S. person, the minimization procedures require that CIA make a determination that the information concerning the U.S. person may be retained outside of access-controlled systems accessible only to CIA personnel with specialized FISA training to review unevaluated information. I

Whereas NSA focused very little attention on its targeting process (which allows it to collect entirely domestic communications), CIA outsources much of its responsibility for limiting intake to FBI and NSA (note, unlike NSA, it includes Title III collection in its report, but also doesn’t treat 704/705b). For example, it focuses on the admittedly close FISA scrutiny FBI applications undergo for traditional FISA targeting, but then acknowledges that it can get “unevaluated” (that is, raw) information in some cases.

If requested by FBI in certain cases, unevaluated information acquired by FBI can be shared with CIA.

Likewise, the CIA notes that it can nominate targets to NSA, but falls back on NSA’s targeting process to claim this is not a bulk collection program (one of CIA’s greatest uses of this data is in metadata analysis).

CIA may nominate targets to NSA for Section 702 collection, but the ultimate decision to target a non-U.S. person reasonably believed to be located outside the United States rests with NSA.

[snip]

Section 702 is not a bulk collection program; NSA makes an individualized decision with respect to each non-U.S. person target.

Thus, the failure of the NSA report to talk about other collection methods (in CIA’s case, of incidental US person data in raw data) ports the same failure onto CIA’s report.

NCTC’s report is perhaps the most amusing of all. It provides the history of how it was permitted to obtain raw Title I and Title III data in 2012 and 702 data in 2017 (like everyone else, it is silent on 704/705b data, though we know from this year’s 702 authorization they get that too), then says its use and dissemination of 702 data is too new to have been reviewed much.

Because NCTC just recently (in April 2017) obtained FISC authority to receive unminimized Section 702-acquired counterterrorism information, only a small number of oversight reviews have occurred. CLPT is directly involved in such reviews, including reviews of disseminations.

In other words, it is utterly silent about its dissemination of Title I and Title III data compliance. It is likewise silent on a dissemination that is probably unique to NCTC: the addition of US person names to watchlists based off raw database analysis. The dissemination of US person names in this way aren’t serialized reports, but they have a direct impact on the lives of Americans.

It’s hard to make sense of the FBI document because it lacks logical organization and includes a number of typos. More importantly, over and over it either materially misrepresents the truth (particularly in FBI’s access to entirely domestic communications collected under 702) or simply blows off requirements (most notably with its insistence that back door searches are important, without making any attempt to assess the privacy impact of them).

Bizarrely, the FBI treats just Title I and 702 in its report, even though it would be in charge of Title III collection in the US, and 705b collection would be tied to traditional FISA authorities.

Like CIA, FBI’s relies on NSA’s role in targeting, without admitting that NSA can collect on selectors that it knows to also be used by US persons, and can disseminate the US person data to FBI in case of a crime. Indeed, FBI specifically neglects to mention the 2014 exception whereby NSA doesn’t have to detask from a facility once it discovers US persons are using it as well as the foreign targets.

Targets under Section 702 collection who are subsequently found to be U.S. persons, or non-U.S. persons located in the U.S., must be detasked immediately

The end result if materially false, and false in a way that would involve dissemination of US person data (though not in a serialized report) from NSA to FBI.

The FBI report also pretends that a nomination would pertain primarily to an email address, rather than (for example) and IP address, in spite of later quoting from minimization procedures that reveal it is far broader than that: “electronic communication accounts/addresses/identifiers.”

After talking about its rules on dissemination, the FBI quickly turns to federated database “checks.”

Among other things, since 9/11, the FBI has dedicated considerable time, effort, and money to develop and operate a federated database environment for its agents and analysts to review information across multiple datasets to establish links between individuals and entities who may be associated with national security and/or criminal investigations. This allows FBI personnel to connect dots among various sources of information in support of the FBI’s investigations, including accessing data collected pursuant to FISA in a manner that is consistent with the statute and applicable FISA court orders. The FBI has done this by developing a carefully overseen system that enables its personnel to conduct database checks that look for meaningful connections in its data in a way that protects privacy and guards civil liberties. Maintaining the capability to conduct federated database checks is critical to the FBI’s success in achieving its mission.

But it doesn’t distinguish the legal difference between dissemination and checks. Far more importantly, it doesn’t talk about the privacy impact of these “checks,” a tacit admission that FBI doesn’t even feel the need to try to justify this from a privacy perspective.

Unlike NSA, FBI talks about the so-called prohibition on reverse targeting.

Reverse targeting is specifically prohibited under Section 702.31 “Reverse targeting” is defined as targeting a non-U.S. person who is reasonably believed to be located outside of the U.S. with the true purpose of acquiring communications of either (1) a U.S. person or (2) any individual reasonably believed to be located inside of the U.S. with whom the non-U.S. person is in contact.32

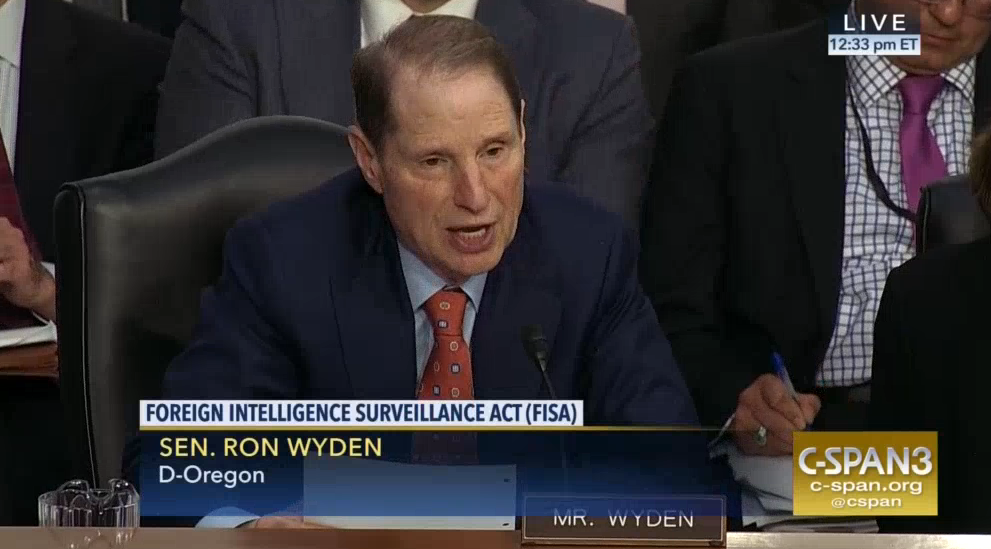

Yet we know from Ron Wyden that this prohibition actually permits FBI to nominate a foreigner even if a purpose of that targeting is to get to the Americans communications.

FBI talks about its new Title I minimization procedures, without mentioning that requirements on access controls and auditing arose in response to violations of such things.

The SMPs require, for example, FISA-acquired information to be kept under appropriately secure conditions that limit access to only those people who require access to perform their official duties or assist in a lawful and authorized governmental function.37 The SMP also impose an auditing requirement for the FBI to “maintain accurate records of all persons who have accessed FISA-acquired information in electronic and data storage systems and audit its access records regularly to ensure that FISA-acquired information is only accessed by authorized individuals.”38

And nowhere does FBI talk about the dissemination of US person data to ad hoc databases.

Remarkably, unlike NSA, FBI didn’t actually appear to review its dissemination practices (at least there’s no described methodology as such). Instead, it reviews its dissemination policy.

The instant privacy review found that the FBI’s SMP and Section 702 MP, which are subject to judicial review, protect the privacy rights of U.S. persons by limiting the acquisition, retention, and dissemination of their non-publicly available information without their consent. In addition, both sets of minimization procedures require that FISA-acquired information only be used for lawful purposes.42

Then it engages in a cursory few line review of whether it complies with FIPP. Whereas NSA assessed compliance with “Transparency, Use Limitation, Data Minimization, Security, Quality and Integrity, Accountability, and Auditing (but found Purpose specification not considered directly relevant), FBI at first assessed only Purpose specification. After noting that such a privacy review is not required in any case because FBI’s systems have been deemed a national security system, it then asserts that “DOJ and FBI conducted a review for internal purposes to ensure that all relevant privacy issues are addressed. These reviews ensure that U.S. person information is protected from potential misuse and/or improper dissemination.”

Later, it uses the affirmative permission to share data with other state and local law enforcement and foreign countries as a privacy limit, finding that it fulfills data minimization and transparency (and purpose, again).

Like the SMP for Title I of FISA, the Section 702 MP permits the FBI to disseminate Section 702-acquired U.S. person information that reasonably appears to be foreign intelligence information or is necessary to understand foreign intelligence information or assess its importance to federal, state, local, and tribal officials and agencies with responsibilities relating to national security that require access to intelligence information.50 The FBI is also permitted to disseminate U.S. person information that reasonably appears to be evidence of a crime to law enforcement authorities.51 In addition, the Section 702 MP provides guidelines that must be met before dissemination of U.S. person information to foreign governments is allowed.52 The dissemination of Section 702 information to a foreign government requires legal review by the NSCLB attorney assigned to the case.53 In light of the above judicially-reviewed minimization procedures for the dissemination of FISA acquired information, the FBI’s current implementation satisfies the data minimization and transparency FIPPs.

With respect to dissemination, FBI focuses on finished intelligence reports, not investigative files, where most data (including data affecting Mike Flynn) would be broadly accessed. Then, far later, it says this review found no violations, “in finished intelligence.”

Finally, the instant review found no indication of noncompliance with the required authorities governing dissemination of U.S. person information in finished intelligence.

At this point, the report appears to be a flashing siren of all the things it either clearly didn’t investigate or wouldn’t describe. Which worries me.

It then turns FBI’s failures to give notice that data derives from FISA as a privacy benefit, rather than a violation of the laws mandating disclosure.

While the redaction of U.S. person information may commonly be referred to as “masking,” the FBI does not generally use that term.

In addition, disseminations or disclosures of FISA-acquired information must be accompanied by a caveat. All caveats must contain, at a minimum, a warning that the information may not be used in a legal proceeding without the advanced authorization of the FBI or Attorney General.48 This helps ensure the information is properly protected.

And in the four paragraphs FBI dedicates to public transparency, it not only doesn’t admit that it has been exempted from most reporting on 702 use, but it doesn’t once mention mandated notice to defendants, which it has only complied with around 8 times.

There are many ways FBI could have handled this report to avoid making it look like a guilty omission that, while its finished intelligence reports aren’t a big US person data dissemination problem, virtually every other way it touches 702 data is. But it didn’t try any of those. Instead, it just engaged in omission after omission.

My unease over the giant holes in the FBI report carry over to a one detail in the DNI report. It’s only there that the government admits something that Semiannual 702 reports have admitted since FBI dispersed targeting to field offices. While the 702 reviews review pretty much everything NSA does and many things CIA does, the reviews don’t review all FBI disseminations, and they only include in their sample disseminations affirmatively identified as US person information.

As it pertains to reviewing dissemination of Section 702 information, ODNI and DOJ’s National Security Division (NSD) review many of the agencies’ disseminations as part of the oversight reviews to assess compliance with each agency’s respective minimization procedures and with statutory requirements.25 NSD and ODNI examine the disseminations to assess whether any information contained therein that appears to be of or concerning U.S. persons meets the applicable dissemination standard found in the agency’s minimization procedures; whether other aspects of the dissemination requirements (to include limitations on the dissemination of attorney-client communications and the requirement of a FISA warning statement as required by 50 U.S.C. § 1806(b)) have been met; and whether the information disseminated is indicative of reverse targeting of U.S. persons or persons located in the United States.

25For example, as it pertains to NSA, NSD currently reviews all of the serialized reports (with ODNI reviewing a sample) that NSA has disseminated and identified as containing Section 702-acquired U.S. person information. For CIA and NCTC, NSD currently reviews all dissemination (with ODNI reviewing a sample) of information acquired under Section 702 that the agency identified as potentially containing U.S. person information. For FBI, both NSD and ODNI currently review a sample of disseminations of information acquired under Section 702 that FBI identifies as potentially containing U.S. person information.

This is one of a number of reasons why FBI only identified one criminal 702 query last year — only after that one query was selected as part of the review, and only after some haranguing, was it identified as an entirely criminal query.

The DNI report makes one more incorrect claim — that all incidents of non-compliance have been remediated.

Disseminating FISA information in a manner that violates the minimization procedures would, therefore, be a violation of the statute, as would use or disclosure of the information for unlawful purposes. As noted above, identified incidents of non-compliance with the minimization procedures, to include improper disseminations, are reported to the FISC and to the congressional intelligence committees and those incidents are remediated.

That was true before this year, I guess. But Rosemary Collyer, in a deviation from past practice of requiring the government to destroy data collected without authorization, did not require NSA to destroy the poison fruit of unauthorized 704b and other back door queries (though perhaps DNI believes their claim is true given the way everyone has avoided talking about the more troubled collection techniques).

The DNI report ends with a boast about what it calls “transparency.”

These reviews also illustrate the importance of transparency. Historically, many of the documents establishing this framework were classified and not available to the public. In recent years, much progress has been made in releasing information from these documents, and providing context and explanations to make them more readily understandable. We trust that these reviews are a further step in enhancing public understanding of these key authorities. It is important to continue with transparency efforts like these on issues of public concern, such as the protection of U.S. person information in FISA disseminations.

It is true that these reports rely on a great deal of declassified information. But that does not amount to “transparency,” unless you’re defining that to mean something that hides the truth with a bunch of off-topic mumbo jumbo.

This report appears to be an attempt to stave off real reporting requirements for unmasked information — an attempt to placate the Republicans who are rightly troubled that the contents of FISA intercepts in which Mike Flynn was incidentally collected.

But no person concerned about the impact on US persons of FISA should find these reports reassuring. On the contrary, the way in which, agency after agency, the most important questions were dodged should raise real alarms, particularly with respect to FBI.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)