I’m now being accused by USA Freedom Act champions of not providing constructive suggestions on how to improve USAF (even though I have, both via channels they were involved in and channels they are not party to) [oops, try this tweet, which is still active].

Now that it appears people who previously claimed I was making all this up now concede some of my critiques as a valid, here goes: my suggestions for how to fix the problems I identified in this post.

Problem: No one will say how the key phone record provision of the bill will work

Fix: Permit the use of correlations — but provide notice to defendants because this is probably unconstitutional warrantless surveillance

There is one application of connection chaining that I find legitimate, and two that are probably unconstitutional. The legitimate application is the burner phone one: to ask providers to use their algorithms (including new profiles of online use) to find the new phones or online accounts that people adopt after dropping previous ones, which is what AT&T offers under Hemisphere. To permit that, you might alter the connection chaining language to say providers can chain on calls and texts made, as well as ask providers to access their own records to find replacement phones. Note, however, that accuracy on this mapping is only about 94% per Hemisphere documents, so it seems there needs to be some kind of check before using those records.

The two other applications — the ones I’m pretty sure are or should be unconstitutional without a warrant — are 1) the use of cloud data, like address books, calendars, and photos, to establish connections, and 2) the use of phone records like Verizon’s supercookie to establish one-to-one correlations between identities across different platforms. I think these are both squarely unconstitutional under the DC Circuit’s Maynard decision, because both are key functions in linking all these metadata profiles together, and language in Riley would support that too. But who knows? I’m not an appellate judge.

To prevent the government from doing this without really independent judicial review — and more generally to ensure Section 215 is not abused going forward — the best fix is to require notice to defendants if any evidence from Section 215 or anything derived from it, including the use of metadata as an index to identify content, is used in a proceeding against them. Given that Section 215’s secret application is now unclassified, they should even get a fairly robust description of how it was used. After all, if this is just third party doctrine stuff, it can’t be all that secret!

Problem: USAF negotiates from a weak position and likely moots potentially significant court gains

Fix (sort of): Provide notice to defendants under Section 215

I’m frankly of the opinion that ACLU’s Alex Abdo kicked DOJ’s ass so thoroughly in the 2nd Circuit, that unless that decision is mooted, it will provide a better halt to dragnets than any legislation could. But I get that that’s a risk, especially with Larry Klayman botching an even better setup in the DC Circuit.

But I do think the one way to make sure we don’t lose the opportunity for a judicial fix to this is to provide notice to defendants of any use or derivative use of Section 215. The government has insisted (most recently in the Reaz Qadir Khan case, but also did so in the Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and derivative cases, where we know they used the phone dragnet) that it doesn’t have to give such notice. If they get it — with the ability to demonstrate that their prosecution arises out of a warrantless mosaic analysis of their lives which provides the basis for the order providing access to their content — then at least there may be a limited judicial remedy in the future, even if it’s not Abdo fighting for his own organization. FISCR said PAA was legal because of precisely these linking procedures, but if they’re not (or if they require a warrant) then PRISM is not legal either. Defendants must have the ability to argue that in court.

Problem: USAF’s effects in limiting bulk collection are overstated

Fix: Put temporal limits on traditional 215 collection, add flexibility into the emergency provision, but adopt existing emergency provision

USAF prohibits using a communications provider corporate person as a selector, but permits the use of a non-communications corporate person as a selector, meaning it could still get all of Visa’s or Western Union’s records. I understand the government claims it needs to retain the use for corporate person selectors to get things like all the guests at Caesars Palace to see if there are suspected terrorists there. The way to permit this, without at the same time permitting a programmatic dragnet (of, say, all Las Vegas hotels all the time), might be to temporally limit the order — say, limit the use of any non-communications provider order to get a month of records.

But this creates a problem, which is that it currently takes (per the NSL IG Report) 30-40 days to get a Section 215 order. The way to make it possible to get records when you need them, rather than keeping a dragnet, is to permit the use of the emergency provision more broadly. You might permit it to be used with counterintelligence uses as well as the current counterterrorism use (that is, make it available in any case where Section 215 would be available), though you should still limit use of any data collected to the purpose for which it was collected. You might even extend the deadline to submit an application beyond 7 days.

That exacerbates the existing problems with the emergency provision, however, which is that the government gets to keep records if the court finds they misused the statute. To fix this, I’d advise tying the change to the adoption of the existing language from the emergency provision currently in place on the phone dragnet order, specifically permitting FISC to require records be discarded if the government shouldn’t have obtained them. I’d also add a reporting requirement on how many emergency provisions were used (that one would be included in the public reporting) and, in classified form to the intelligence and judiciary committees, fairly precisely what it had been used for. I’d additionally require FBI track this data, so it can easily report what has become of it.

Given that the government may have already abused the emergency provisions, this requires close monitoring. So no loosening of the emergency provision should be put into place without the simultaneous controls.

Problem: USAF would eliminate any pushback from providers

Fix: Put “good faith” language back in the law and provide appeal of demand for proprietary requests

I’d do two things to fix the current overly expansive immunity provisions. First, I’d put the language that exists in other immunity provisions requiring good faith compliance with orders, such that providers can’t be immunized for stuff that they recognize is illegal.

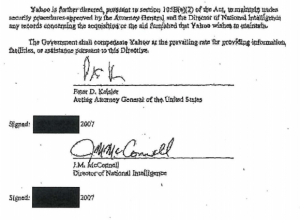

I’d also add language giving them an appeal if the government were obtaining proprietary information. While under current law the government should be able to obtain call records, they shouldn’t be able to require providers also share their algorithms about business records, which is (I suspect) where this going (indeed, the Yahoo documents suggest that’s where it has already gone under PRISM). So make it clear there’s a limit to what is included under third party doctrine, and provide providers with a way to protect their data derived from customer records.

Problem: USAF may have the effect of weakening existing minimization procedures

Fix: Include language permitting FISC approval and review of compliance with traditional 215 minimization procedures and PRTT, adopt emergency provision language currently in place

This should be simple. Just include language letting the court review minimization procedures and review compliance, which is currently what happens and should happen as we get deeper and deeper into mosaic collection (indeed, this might be pitched as a solution to what should be a very urgent constitutional problem for the status quo practice).

Additionally, the bill should integrate the emergency provision currently applicable to the phone dragnet for all Section 215 use, along with reporting on how often and how it is used.

Both of these, importantly, simply codify the current status quo. If the government won’t accept the current status quo, after years of evidence on why it needs this minimal level of oversight from FISC, then that by itself should raise questions about the intelligence community’s intent going forward.

Problem: USAF’s transparency provisions are bullshit

Fix: Require reporting from all providers, give FBI 2 years and a budget to eliminate exemptions, give NSA 2 years to be able to answer all questions

One minimal fix to the transparency provisions is to require reporting not just from all communications providers, but from all providers who have received orders, such that the government would have to report on financial and location dragnets, which are both currently excluded. This would ensure that financial and location dragnets that currently exist and are currently exempted from reporting are included.

As to the other transparency provisions, the biggest problem is that the bill permits both the NSA and FBI to say “omigosh we simply can’t count all this.” I think they’re doing so for different reasons. In my opinion, the NSA is doing so because it is conducting illegal domestic wiretapping, especially to pursue cybersecurity targets. It is doing so because it hasn’t gotten Congress to buy off on using domestic wiretapping to pursue cybertargets. I would impose a 2 year limit on how long ODNI can avoid reporting this number, which should provide plenty of time for Congress to legislate a legal way to pursue cybertargets (along with limits to what kind of cybertargets merit such domestic wiretapping, if any).

I think the FBI refusing to count its collection because it wants to passively collect huge databases of US persons so it can just look up whether people who come under its radar are suspicious. I believe this is unconstitutional — it’s certainly something the government lied to the FISCR in order to beat back Yahoo’s challenge, and arguably the government made a similar lie in Amnesty v. Clapper. If I had my way, I’d require FBI to count how many US persons it was collecting on and back door searching yesterday. But if accommodation must be made, FBI, too, should get just 2 years (and significant funding) to be able to 1) tag all its data (as NSA does, so most of it would come tagged) 2) count it and its back door searches 3) determine whether incoming data is of interest within a short period of time, rather than sitting on it for 30 years. Ideally, FBI would also get 2 years to do the same things with its NSL data.

Again, I think the better option is just to make NSA and FBI count their data, which will show both are violating the Constitution. Apparently, Congress doesn’t want to make them do that. So make them do that over the next 2 years, giving them time to replace unconstitutional programs.

Problem: Other laudable provisions — like the Advocate — will easily be undercut

Fix: Add exemption in the ex parte language on FISA review for the advocate

In this post, I noted that the provision requiring the advocate have all the material she needs to do to do her job conflicts with the provision permitting the government to withhold information on classification or privilege grounds. If there is any way to limit this — perhaps by requiring the advocate be given clearance into any compartments for the surveillance under question (though not necessarily the underlying sources and methods used in an affidavit), as well as mandating that originator controlled (ORCON) documents be required to be shared. This might work like a CIPA provision, that the government must be willing to share something if it wants FISC approval (and with it, the authority to obligate providers).

But since that post, we’ve seen how, in the Yahoo challenge, the government convinced Reggie Walton to apply the ex parte provisions applying to defendants to Yahoo. That precedent would now, in my opinion, apply language on review to any adversary. To fix that, the bill should include conforming language in all the places (such as at 50 USC 1861(c)) that call for ex parte review to make it clear that ex parte review does not apply to an advocate’s review of an order.

I fully expect the IC to find this unacceptable (Clapper has already made it clear he’ll only accept an advocate that is too weak to be effective). But bill reformers should point to the clear language in the President’s speech calling for “a panel of advocates from outside government to provide an independent voice in significant cases before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.” If the IC refuses to have an advocate that can do the job laid out by statute, they should have to answer to the President, who has called for real advocates (not amici).

To recap — all this pertains only to the bill on its face, not to the important things the bill is missing, such as a prohibition on back door searches. But these are things that would make USA Freedom Act far better.

I suspect the intelligence community would object to many, if not all of them. But if they do, then it would certainly clarify what their intent really is.