SEN. MIKULSKI: General Clapper, there are 36 different legal opinions.

DIR. CLAPPER: I realize that.

SEN. MIKULSKI: Thirty-six say the program’s constitutional. Judge Leon said it’s not.

Thirty-six “legal opinions” have deemed the dragnet legal and constitutional, its defenders say defensively, over and over again.

But that’s not right — not by a long shot, as ACLU’s Brett Max Kaufman pointed out in a post yesterday. In its report, PCLOB confirmed what I first guessed 4 months ago: the FISA Court never got around to writing an opinion considering the legality or constitutionality of the dragnet until August 29, 2013.

FISC judges, on 33 occasions before then, signed off on the dragnet without bothering to give it comprehensive legal review.

Sure, after the program had been reauthorized 11 times, Reggie Walton considered the more narrow question of whether the program violates the Stored Communications Act (I suspect, but cannot yet prove, that the government presented that question because of concerns raised by DOJ IG Glenn Fine). But until Claire Eagan’s “strange” opinion in August, no judge considered in systematic fashion whether the dragnet was legal or constitutional.

And the thing is, I think FISC judge — now Presiding Judge — Reggie Walton realized around about 2009 what they had done. I think he realized the program didn’t fit the statute.

Consider a key problem with the dragnet — another one I discussed before PCLOB (though I was not the first or only one to do so). The wrong agency is using it.

Section 215 does not authorize the NSA to acquire anything at all. Instead, it permits the FBI to obtain records for use in its own investigations. If our surveillance programs are to be governed by law, this clear congressional determination about which federal agency should obtain these records must be followed.

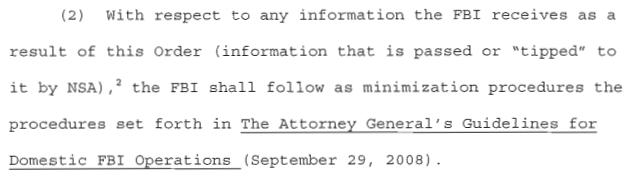

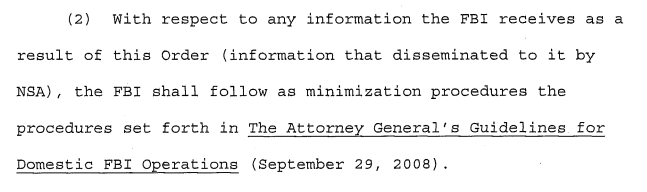

Section 215 expressly allows only the FBI to acquire records and other tangible things that are relevant to its foreign intelligence and counterterrorism investigations. Its text makes unmistakably clear the connection between this limitation and the overall design of the statute. Applications to the FISA court must be made by the director of the FBI or a subordinate. The records sought must be relevant to an authorized FBI investigation. Records produced in response to an order are to be “made available to,” “obtained” by, and “received by” the FBI. The Attorney General is directed to adopt minimization procedures governing the FBI’s retention and dissemination of the records it obtains pursuant to an order. Before granting a Section 215 application, the FISA court must find that the application enumerates the minimization procedures that the FBI will follow in handling the records it obtains. [my emphasis, footnotes removed]

The Executive convinced the FISA Court, over and over and over, to approve collection for NSA’s use using a law authorizing collection only by FBI.

Which is why I wanted to point out something else Walton cleaned up in 2009, along with watchlists of 3,000 Americans who had not received First Amendment Review. Judge Reggie Walton disappeared the FBI Director.

>>>Poof!<<<

Gone.

The structure of all the dragnet orders released so far (save Eagan’s opinion) follow a similar general structure:

- An (unnumbered, unlettered) preamble paragraph describing that the FBI Director made a request

- 3-4 paragraphs measuring the request against the statute, followed by some “wherefore” language

- A number of paragraphs describing the order, consisting of the description of the phone records required, followed by 2 minimization paragraphs, the first pertaining to FBI and,

- The second paragraph introducing minimization procedures for NSA, followed by a larger number of lettered paragraphs describing the treatment of the records and queries (this section got quite long during the 2009 period when Walton was trying to clean up the dragnet and remains longer to this day because of the DOJ oversight Walton required)

Here’s how the first three paragraphs looked in the first order and (best as I can tell) the next 11 orders, including Walton’s first order in December 2008:

An application having been made by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for an order pursuant to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (the Act), Title 50, United States Code (U.S.C.), § 1861, as amended, requiring the production to the National Security Agency (NSA) of the tangible things described below, and full consideration having been given to the matters set forth therein, the Court finds that:

1. The Director of the FBI is authorized to make an application for an order requiring the production of any tangible thing for an investigation to obtain foreign intelligence information not concerning a United States person or to protect against international terrorism, provided that such an investigation of a United States person is not conducted solely on the basis of activities protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. [50 U.S.C. § 1861 (c)(1)]

2. The tangible things to be produced are all call-detail records or “telephone metadata” created by [the telecoms]. Telephone metadata includes …

[snip]

3. There are reasonable grounds to believe that the tangible things sought are relevant to authorized investigations (other than threat assessments) being conducted by the FBI under guidelines approved by the Attorney General under Executive Order 12,333 to protect against international terrorism, … [my emphasis]

Here’s how the next order and all (released) following orders start [save the bracketed language, which is unique to this order]:

An verified application having been made by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for an order pursuant to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA), as amended, 50 U.S.C. § 1861, requiring the production to the National Security Agency (NSA) of the tangible things described below, and full consideration having been given to the matters set forth therein, [as well as the government’s filings in Docket Number BR 08-13 (the prior renewal of the above-captioned matter),] the Court finds that:

1. There are reasonable grounds to believe that the tangible things sought are relevant to authorized investigations (other than threat assessments) being conducted by the FBI under guidelines approved by the Attorney General under Executive Order 12333 to protect against international terrorism, …

That is, Walton took out the paragraph — which he indicated in his opinion 3 months earlier derived from the statutory language at 50 U.S.C. § 1861 (c)(1) — pertaining to the FBI Director. The paragraph always fudged the issue anyway, as it doesn’t discuss the FBI Director’s authority to obtain this for the NSA. Nevertheless, Walton seems to have found that discussion unnecessary or unhelpful.

Walton’s March 5, 2009 order and all others since have just 3 statutory paragraphs, which basically say:

- The tangible things are relevant to authorized FBI investigations conducted under EO 12333 — Walton cites 50 USC 1861 (c)(1) here

- The tangible things could be obtained by a subpoena duces tecum (50 USC 1861 (c)(2)(D)

- The application includes an enumeration of minimization procedures — Walton doesn’t cite statute in this May 5, 2009 order, but later orders would cite 50 USC 1861 (c)(1) again

Here’s what 50 USC 1861 (c)(1), in its entirety, says:

(1) Upon an application made pursuant to this section, if the judge finds that the application meets the requirements of subsections (a) and (b), the judge shall enter an ex parte order as requested, or as modified, approving the release of tangible things. Such order shall direct that minimization procedures adopted pursuant to subsection (g) be followed.

And here are two key parts of subsections (a) and (b) — in addition to “relevant” language that has always been included in the dragnet orders.

(a) Application for order; conduct of investigation generally

(1) Subject to paragraph (3), the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation or a designee of the Director (whose rank shall be no lower than Assistant Special Agent in Charge) may make an application for an order requiring the production of any tangible things

[snip]

(2) shall include—

[snip]

(B) an enumeration of the minimization procedures adopted by the Attorney General under subsection (g) that are applicable to the retention and dissemination by the Federal Bureau of Investigation of any tangible things to be made available to the Federal Bureau of Investigation based on the order requested in such application.

FBI … FBI … FBI.

The language incorporated in 50 USC 1861 (c)(1) that has always been cited as the standard judges must follow emphasizes the FBI repeatedly (PCLOB laid out that fact at length in their analysis of the program). And even Reggie Walton once admitted that fact.

And then, following his lead, FISC stopped mentioning that in its statutory analysis altogether.

Eagan didn’t even consider that language in her “strange” opinion, not even when citing the passages (here, pertaining to minimization) of Section 215 that directly mention the FBI.

Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act created a statutory framework, the various parts of which are designed to ensure not only that the government has access to the information it needs for authorized investigations, but also that there are protections and prohibitions in place to safeguard U.S. person information. It requires the government to demonstrate, among other things, that there is “an investigation to obtain foreign intelligence information … to [in this case] protect against international terrorism,” 50 U.S.C. § 1861(a)(1); that investigations of U.S. persons are “not conducted solely upon the basis of activities protected by the first amendment to the Constitution,” id.; that the investigation is “conducted under guidelines approved by the Attorney General under Executive Order 12333,” id. § 1861(a)(2); that there is “a statement of facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the tangible things sought are relevant” to the investigation, id. § 1861(b)(2)(A);14 that there are adequate minimization procedures “applicable to the retention and dissemination” of the information requested, id. § 1861(b)(2)(B); and, that only the production of such things that could be “obtained with a subpoena duces tecum” or “any other order issued by a court of the United States directing the production of records” may be ordered, id. § 1861(c)(2)(D), see infra Part III.a. (discussing Section 2703(d) of the Stored Communications Act). If the Court determines that the government has met the requirements of Section 215, it shall enter an ex parte order compelling production.

This Court must verify that each statutory provision is satisfied before issuing the requested Orders. For example, even if the Court finds that the records requested are relevant to an investigation, it may not authorize the production if the minimization procedures are insufficient. Under Section 215, minimization procedures are “specific procedures that are reasonably designed in light of the purpose and technique of an order for the production of tangible things, to minimize the retention, and prohibit the dissemination, of nonpublicly available information concerning unconsenting United States persons consistent with the need of the United States to obtain, produce, and disseminate foreign intelligence information.” Id. § 1861(g)(2)(A)

Reggie Walton disappeared the FBI Director as a statutory requirement (he retained that preamble paragraph, the nod to authorized FBI investigations, and the perfunctory paragraph on minimization of data provided from NSA to FBI) on March 5, 2009, and he has never been heard from in discussions of the FISC again.

Now I can imagine someone like Steven Bradbury making an argument that so long as the FBI Director actually signed the application, and so long as the FBI had minimization procedures for the as few as 16 tips they receive from the program in a given year, it was all good to use an FBI statute to let the NSA collect a dragnet potentially incorporating all the phone records of all Americans. I can imagine Bradbury pointing to the passive construction of that “things to be made available” language and suggest so long as there were minimization procedures about FBI receipt somewhere, the fact that the order underlying that passive voice was directed at the telecoms didn’t matter. That would be a patently dishonest argument, but not one I’d put beyond a hack like Bradbury.

The thing is, no one has made it. Not Malcolm Howard in the first order authorizing the dragnet, not DOJ in its request for that order (indeed, as PCLOB pointed out, the application relied heavily on Keith Alexander’s declaration about how the data would be used). The closest anyone has come is the white paper written last year that emphasizes the relevance to FBI investigations.

But no one I know of has affirmatively argued that it’s cool to use an FBI statute for the NSA. In the face of all the evidence that the dragnet has not helped the FBI thwart a single plot — maybe hasn’t even helped the FBI catch one Somali-American donating less than $10,000 to al-Shabaab, as they’ve been crowing for months — FBI Director Jim Comey has stated to Congress that the dragnet is useful to the FBI primarily for agility (though the record doesn’t back Comey’s claim).

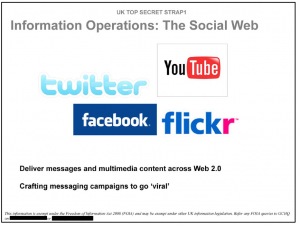

Which leaves us with the only conclusion that makes sense given the Executive’s failure to prove it is useful at all: it’s not the FBI that uses it, it’s NSA. They don’t want to tell us how the NSA uses it, in part, because we’ll realize all their reassurances about protections for Americans fall flat for the millions of Americans who are 3 degrees away from a potential suspect.

But they also don’t want to admit that it’s the NSA that uses it, because then it’ll become far more clear how patently illegal this program has been from the start.

Better to just disappear the FBI Director and hope no one starts investigating the disappearance.