Conclusion To Series on The Reconstruction Era

This series was motivated by recent scholarship arguing that the Reconstruction Amendments, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, gave our nation a new beginning, one centered on equality of citizens. I discussed The Nation That Never Was by Kermit Roosevelt; The Second Founding by Eric Foner, and Beloved by Toni Morrison, I also discussed several Supreme Court cases from that era, The Slaughterhouse Cases, US v. Cruikshank, and The Civil Rights Cases; and several recent SCOTUS cases continuing their foul legacy. Enough. Here are some final thoughts.

1. Once again I’m reminded of the astonishing amount I don’t know. I think my education as a young person was reasonably solid. But I have no memory of any of the history I’ve discussed in this series. As I recall, I was taught that we passed the Reconstruction Amendments after the Civil War, that Johnson was impeached, and that Grant was corrupt. Then we learned about a the civil service laws, a little early labor history, the financial collapses caused by speculators and frauds, and the reforms of the Progressive Era. I didn’t learn about Plessy v. Ferguson until my first mandatory history course in college. It’s worse today, of course.

Much of what I’ve written about here is posted under Left Theory, because I’ve tried to focus on abstract ideas that might provide a framework for thinking about a left version of the future. It’s hard to get worked up about ideas, which suited me as I didn’t want to write rage posts. But there’s nothing abstract about this series.

I was enraged from the beginning by the insistence of the Founding Fathers on enabling a brutal slave system while yammering about Enlightenment Ideals. Thomas Jefferson enslaved his own children with Sally Hemings even as he claimed that all men are created equal. Maybe Roosevelt is right to say Jefferson was talking about the state of nature but the contrast between ideas and practice is grotesque and disgusting. How are we supposed to accommodate it in our veneration of the Founding Fathers?

The Reconstruction Amendments were drafted by men who had waged and survived the Civil War, knew that the slavers started it, and wanted to stamp out slavery as part of the crushing victory they achieved. Voters elected Senators and Representatives who knew that the slavers had never accepted defeat; that they intended to enforce White Supremacy by force and by legalized resistance, the KKK or state legislatures. Between 1865 and 1875 Congress enacted numerous laws to enforce equal rights for all citizens, regardless of race.

The Supreme Court refused to recognize the Reconstruction Amendments or laws passed pursuant to those amendments. They read the Privileges and Immunities Clause out of the 14th Amendment. They narrowed all three amendments, and ignored the part giving Congress the power to legislate to enforce ir known purpose. Congress passed more laws, and the Supreme Court swatted them away. The Court intentionally substituted its policy preferences for those of the elected branches of government.

I’ve never claimed to be an expert in any of the areas I’ve written about here at Emptywheel. I only claim to be willing to engage with the text and to try to give it a fair reading. But this was simply too emotionally charged. Maybe someone else could read this material as if it were an essay by John Locke, but not me. And to think that a vast majority of moraly and intellectually deficient Red State politicians want to walk away from it — no. Just no.

2. Much of the material in the last part of the series revolves around the role of the Supreme Court and its centuries of rejection of majority rule. But that’s not the whole story. If a majority of White voters thought the Freedmen and their own Black neighbors were their equals they could have forced change one way or another. But while many, perhaps most, white people were sympathetic, that didn’t mean they were ready to accept Black people as equals.

This point is illustrated by a scene in Beloved. Long after the end of the Civil War Denver, a Black woman, desperately needs a job. She goes to the home of the Bodwin’s, the people who helped her grandmother and mother afterthey escaped from slavery. She knocks on the front door, and Janey Wagon, the Bodwin’s maid, opens it.

“Yes?”

“May I come in?”

“What you want?”

….

“I’m looking for work. I was thinking they might know of some.”

“You Baby Suggs’ kin, ain’t you?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Come on in. You letting in flies.” She led Denver toward the kitchen, saying, “First thing you have to know is what door to knock on.” P. 297-8.

Even the Bodwin’s, who were aggressively anti-slavery, didn’t let Black people enter at the front door. I’d guess this was the dominant attitude in that era. Citizenship was one thing. But there was little, if any, support for social equality.

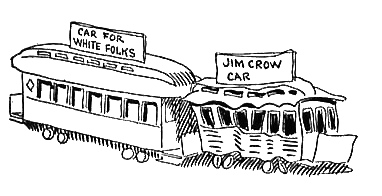

One piece of evidence supporting the view that the national consensus was that social equality was impossible can be found in a 1910 editorial in the New York Times, supporting a Jim Crow law requiring separation of Black and White people on railroad cars in interstate commerce. The Times says the case, Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio RR, reverses an earlier decision barring such discrimination.

The present decision reveals the influence of the change in public opinion since the reconstruction era: it justifies both the law and compliance with it by the carrier, and permits the rest of the Southern States to amend their “Jim Crow” laws after the example of Kentucky.

The Southern Legislatures, thwarted during the first years following the civil war in their efforts to separate negroes from whites in public conveyances, have gradually passed laws to this effect in every State save Missouri, and the courts have sustained them.

Without public opinion on their side, Black people were left to their own devices, treated as second-class citizens by state and federal governments. Over time the national mood turned into indifference to violent White Supremacist attacks on Black People. This mood was reflected in Supreme Court decisions in cases like Plessy v. Ferguson. That indifference didn’t even begin to change until the 1950s. White Supremacists, closet racists, and pandering politicians continue to fight a rear-guard action with plenty of wins.

That thought takes the edge off the fury and exposes a deeper layer of emotions: sadness that just like the Founding Fathers we do not live up to our professed ideals.