The Most Complex Friday Night News Dump, Ever?

President Trump arrived late to a healthcare announcement yesterday and didn’t take any questions.

Starting around the same time, DOJ launched some of the most complexly executed Friday Night News dumps going.

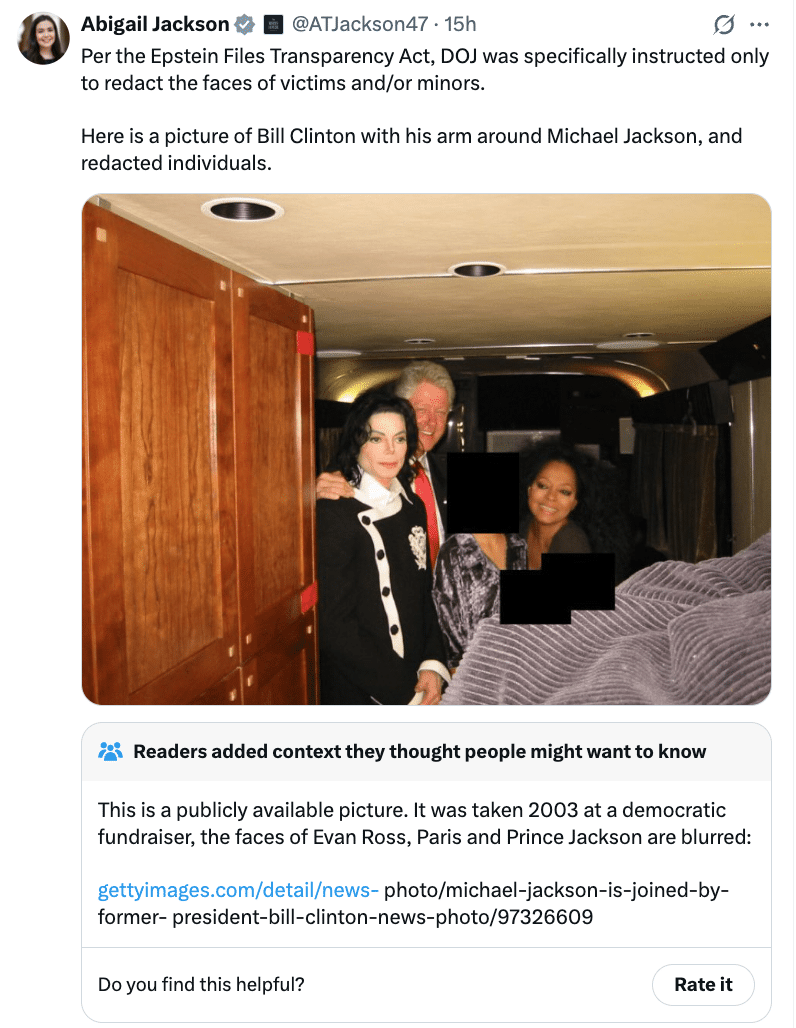

Epstein Limited Hangout

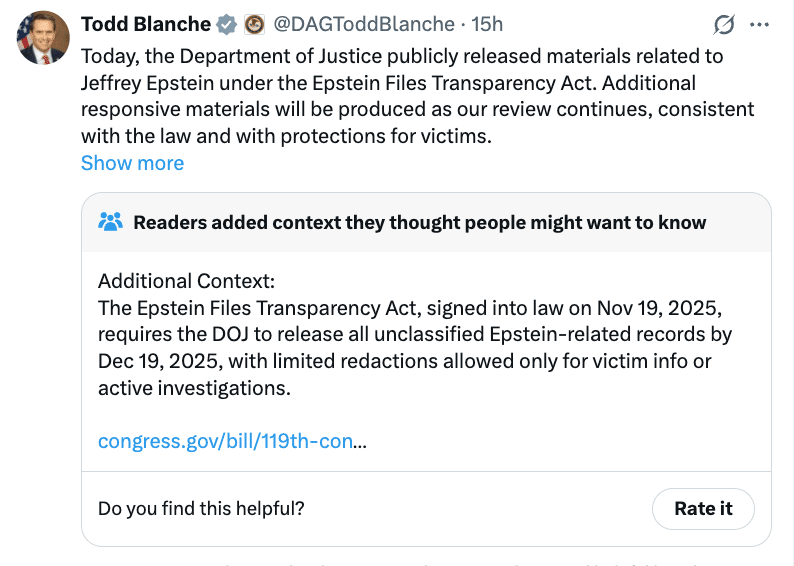

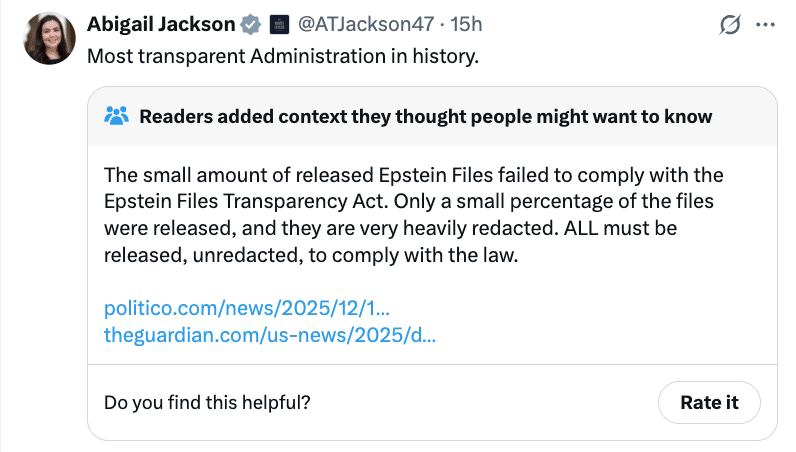

The big attraction was the release of the first batch of the Epstein files. The limited release violates the law, which required all files to be released yesterday.

Instead, there were a whole bunch of Bill Clinton photos, the document reflecting Maria Farmer’s complaint from 1996, that went ignored for years, and redacted grand jury transcripts that clearly violate the law. [Update: They have now released the SDNY ones.] The government did not release the proposed indictment and prosecution memo for the indictment that should have been filed in 2007; that may be sealed as deliberative.

Todd Blanche’s wildly dishonest letter (particularly with regards to his claimed concern for victims, after being admonished repeatedly by judges for failing to take that responsibility seriously and a last minute bid that promised but failed to put Pam Bondi on the phone) explaining the release emphasizes how Bondi took over a hundred national security attorneys off their job hunting hackers and spies to conduct a second review; it does not mention the even bigger review the FBI accomplished in March.

The review team consisted of more than 200 Department attorneys working to determine whether materials were responsive under the Act and. if so, whether redactions or withholding was required, The review had multiple levels. First, 187 attorneys from the Department’sNational Security Division (NSD) conducted a review of all items produced to JMD for responsiveness and any redactions under the Act. Second, a quality-control team of 25 attorneys conducted a second-level review to ensure that victim personally identifying information wasproperly redacted and that materials that should not be redacted were not marked for redaction.The second-level review team consisted of attorneys from the Department’s Office of Privacy and Civil Liberties (OPCL) and Office of Information Policy (OIP)—these attorneys are experts in privacy rights and reviewing large volumes of discovery. After the second-level review team completed its quality review, responsive materials were uploaded onto the website for public production as required under the Act. See Sec. 2(a). Finally, Assistant United States Attorneys from the Southern District of New York reviewed the responsive materials to confirm appropriate redactions so that the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York could certify that victim identifying information was appropriately protected.

That John Eisenberg’s department was in charge of a second pass on these documents is of some interest; there’s no specific competence Nat Sec attorneys would have, but Eisenberg has helped Trump cover stuff up in the past, most notably the transcript of his perfect phone call with Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Thus far the limited hangout has shifted the focus onto Clinton and away from Trump, but as Kyle Cheney lays out, it risks creating a WikiLeaks effect, in which a focus remains on Epstein for weeks or even months.

Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche confirmed Friday that the documents would be released on a rolling basis through the holidays — and possibly beyond. And, in court papers filed shortly after Friday’s partial release, the Justice Department emphasized that more files are still undergoing a review and redaction process to protect victims and new Trump-ordered investigations before they can be released.

The daily drip is a remarkable result for President Donald Trump, who has urged his allies to move past the Epstein files — prompting jeers from Democrats who say he’s trying to conceal details about his own longtime relationship with Epstein. Trump has maintained for years that he and Epstein had a falling out years ago, and no evidence has suggested that Trump took part in Epstein’s trafficking operation. Trump advocated for the release of the files only after Republicans in Congress rebuffed his initial pleas to keep them concealed.

[snip]

Trump is no stranger to the political power of intermittent disclosures of derogatory information. In 2016, Trump led the charge to capitalize on the hack-and-leak operation that led to daily publications of the campaign emails of Hillary Clinton and her top allies. The steady drumbeat of embarrassing releases — amplified by Trump and a ravenous press corps — helped sink Clinton’s campaign in its final weeks.

And that’s before the political and legal response to this limited hangout. Some victims are already expressing disappointment — most notably, by the redaction of grand jury material and names they know they shared, as well as the draft indictment from Florida.

Tom Massie and Ro Khanna, while originally giving DOJ the benefit of the doubt, are now contemplating measures they can take — potentially including contempt or impeachment — to enforce this law.

After Fox News was the first to report that the names of some politically exposed persons would be redacted, DOJ’s favorite transcriptionist Brooke Singman told a different story.

And Administration officials are getting burned by Elon’s fascism machine for their dishonesty.

Once again, Trump’s top flunkies may be overestimating their ability to contain their scandal.

Todd Blanche behind the selective prosecution

Meanwhile, efforts by those same flunkies to punish Kilmar Abrego continue to impose costs.

There have been parallel proceedings with Abrego in the last month. Just over a week ago in his immigration docket, Judge Paula Xinis ordered Kilmar Abrego to be released from ICE custody for the first time since March, and then issued another order enjoining DHS from taking him back into custody at a check-in the next day. Effectively, Xinis found the government had been playing games for months, making claims they had plans to ship Abrego to one or another African country instead of Costa Rica, which had agreed to take him. Those games were, in effect, admission they had no order of removal for him, and so could no longer detain him.

[B]ecause Respondents have no statutory authority to remove Abrego Garcia to a third country absent a removal order, his removal cannot be considered reasonably foreseeable, imminent, or consistent with due process. Although Respondents may eventually get it right, they have not as of today. Thus, Abrego Garcia’s detention for the stated purpose of third country removal cannot continue.

But even as that great drama was happening, something potentially more dramatic was transpiring in Abrego’s criminal docket.

Back on December 4, Judge Waverly Crenshaw, who had been receiving, ex parte, potential evidence he ordered the government turn over in response to Abrego’s vindictive prosecution claim, canceled a hearing and kicked off a fight over disclosures with DOJ. Four days later he had a hearing with the government as part of their bid for partial reconsideration, but then provided a limited set of exhibits to Kilmar’s attorneys.

Then yesterday, in addition to a request that Judge Crenshaw gag Greg Bovino — who keeps lying about Abrego — Abrego’s team submitted filings in support of the bid to dismiss the indictment. One discloses that Todd Blanche’s office was pushed by people within Blanche’s office, including Aakash Singh, who is centrally involved in Blanche’s other abuse of DOJ resources, including by targeting George Soros.

Months ago now, this Court recognized that Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche’s “remarkable” admission that this case was brought because “a judge in Maryland…questioned” the government’s decision to deport Mr. Abrego and “accus[ed] us of doing something wrong”1 may “come close to establishing actual vindictiveness.” (Dkt. 138 at 7-8). The only thing the Court found missing from the record was evidence “tying [Mr. Blanche’s statements] to actual decisionmakers.” (Id. at 8). Not anymore. Previously, the Court rightly wondered who placed this case on Mr. McGuire’s desk and what their motivations were. (Dkt. 185 at 2). We now know: it was Mr. Blanche and his office, the Office of the Deputy Attorney General, or “ODAG.” On April 30, 2025, just three days after Mr. McGuire personally took on this case, one of Mr. Blanche’s chief aides, Associate Deputy Attorney General Aakash Singh, told Mr. McGuire that this case was a [redacted]2 (Abrego-Garcia000007). That same day, Mr. Singh asked Mr. McGuire: [redacted] (Abrego-Garcia000008). Mr. McGuire responded with a timing update, saying he wanted to about a strategic question, and assuring Mr. Singh [redacted] and [redacted] (Abrego-Garcia000008). These communications and others show, as the Court put it, that [redacted] and [redacted] (Dkt. 241 at 5, 7). The “remarkable” statements “com[ing] close” to establishing vindictiveness (Dkt. 138 at 7-8) came from the same place— ODAG—as the instructions to Mr. McGuire to charge this case. The only “independent” decision (Dkt. 199 at 1) Mr. McGuire made was whether to acquiesce in ODAG’s directive to charge this case, or risk forfeiting his job as Acting U.S. Attorney—and perhaps his employment with the Department of Justice—for refusing to do the political bidding of an Executive Branch that is avowedly using prosecutorial power for “score settling.”3

2 The Court’s December 3 opinion (Dkt. 241) remains sealed, and the discovery produced to the defense in connection with Mr. Abrego’s motion to dismiss for vindictive and selective prosecution was provided pursuant to a protective order requiring that “[a]ny filing of discovery materials must be done under seal pending further orders of this Court” (Dkt. 77 at 2). Although the defense does not believe that any of these materials should be sealed for the reasons stated in Mr. Abrego’s memorandum of law regarding sealing (Dkt. 264), the defense is publicly filing a redacted version of this brief out of an abundance of caution pending further orders of the Court.

3 See Chris Whipple, Susie Wiles Talks Epstein Files, Pete Hegseth’s War Tactics, Retribution, and More (Part 2 of 2), Vanity Fair (Dec. 16, 2025), https://www.vanityfair.com/news/story/trump-susie-wiles-interview-exclusive-part-2.

While the specific content of this discovery remains redacted, the gist of it is clear: Blanche’s office ordered Tennessee prosecutors to file charges against Abrego in retaliation for his assertion of his due process rights.

We know similar documents exist in other cases — most notably, that of LaMonica McIver, Jim Comey, and Letitia James — but no one else has succeeded in getting their hands on the proof.

The Jim Comey stall

Speaking of which, the news you heard about yesterday is that DOJ filed its notice of appeal in both the Jim Comey and Letitia James’ dismissals.

The move comes after DOJ tried to indict James again in Norfolk on December 4 and then tried again in Alexandria on December 11, after which the grand jury made a point of making the failure (and the new terms of the indictment, which Molly Roberts lays out here) clear; Politico first disclosed the Alexandria filings here.

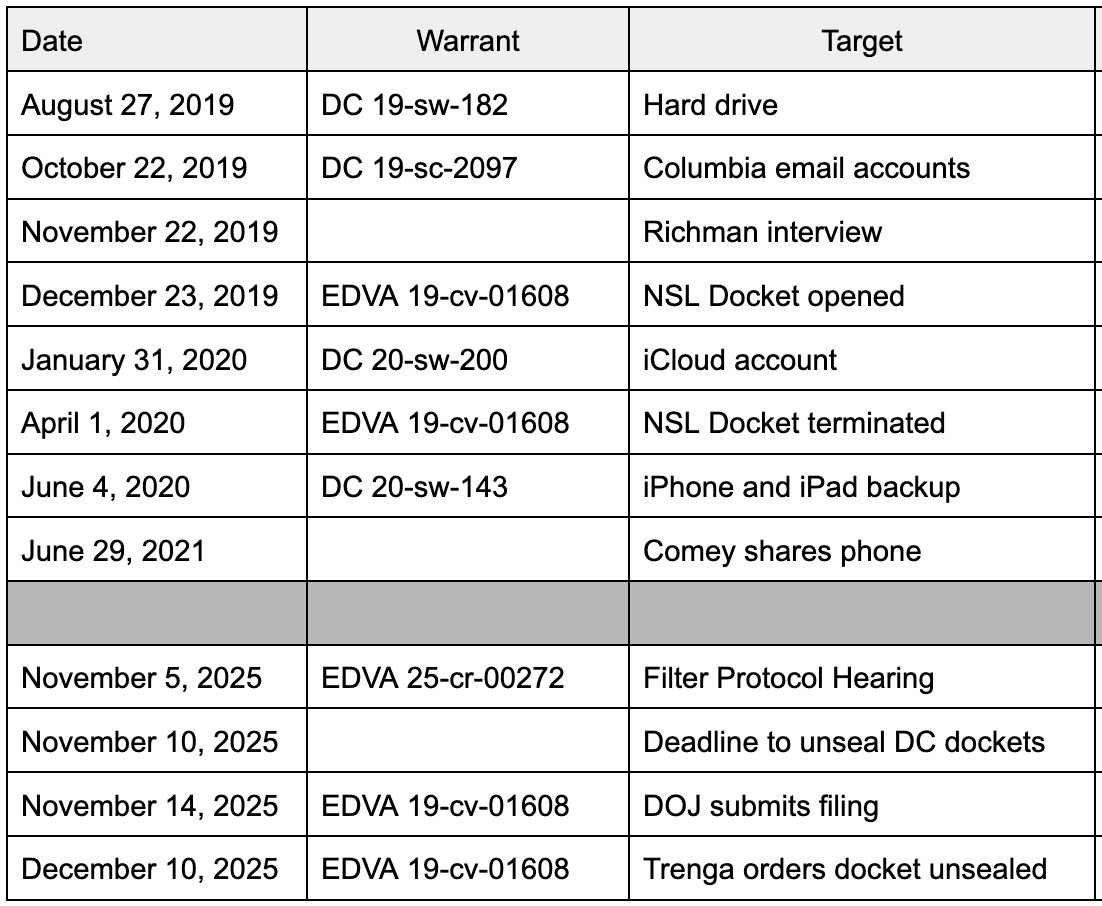

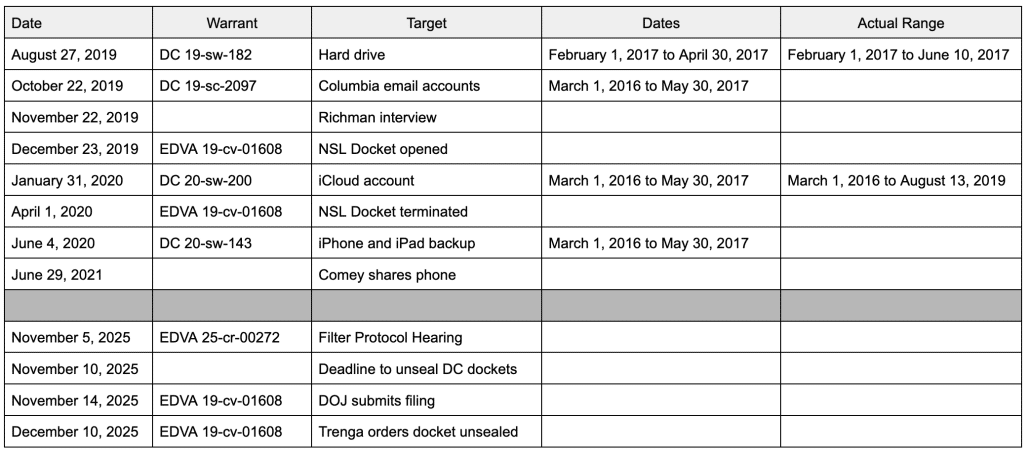

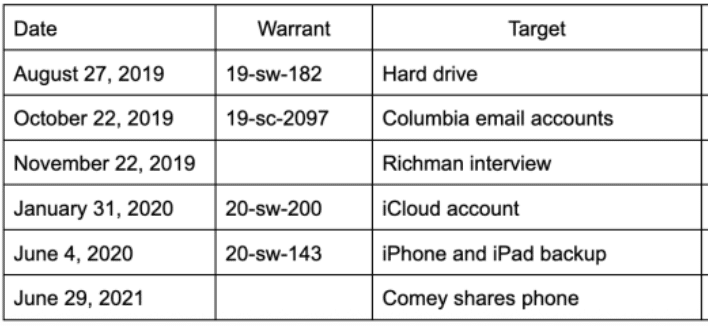

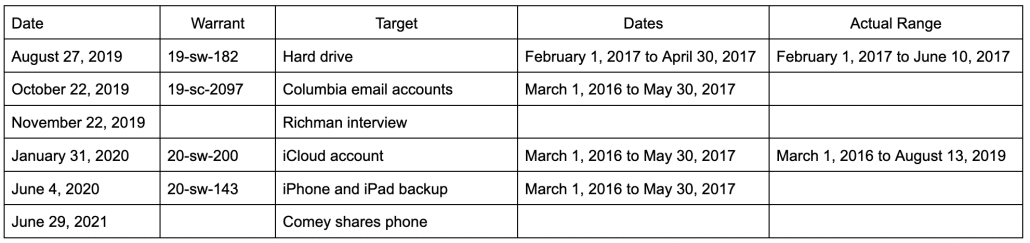

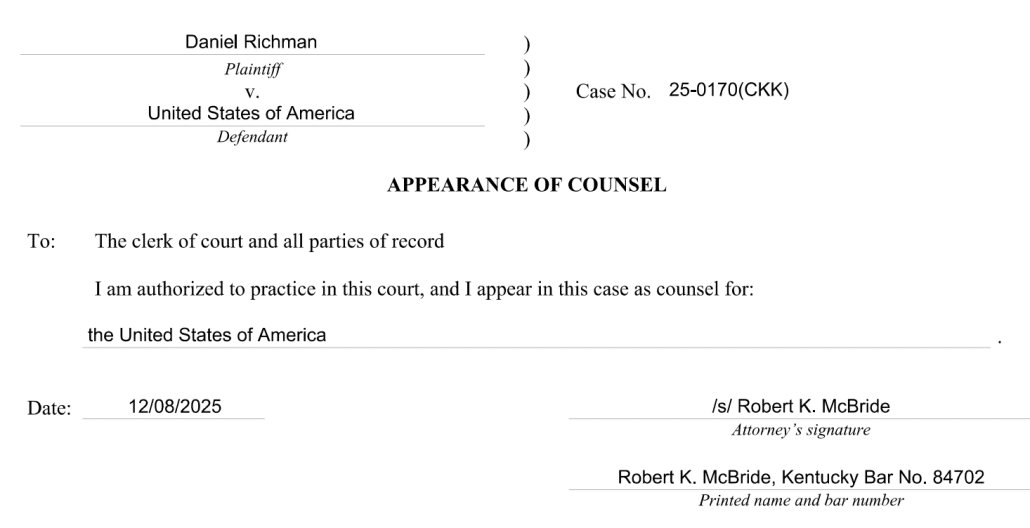

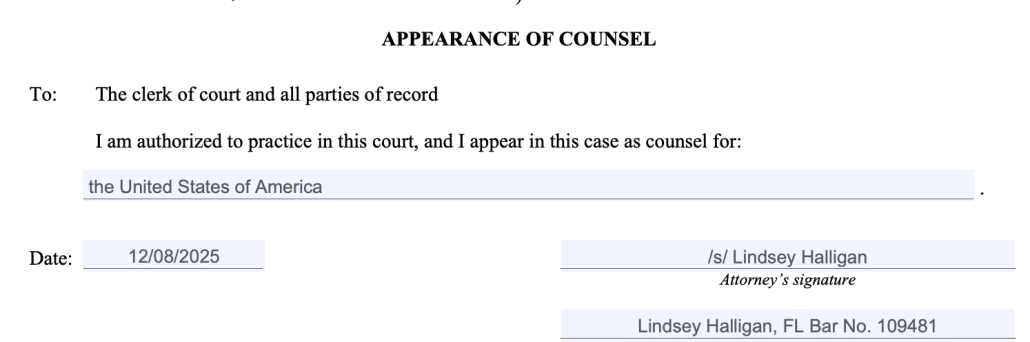

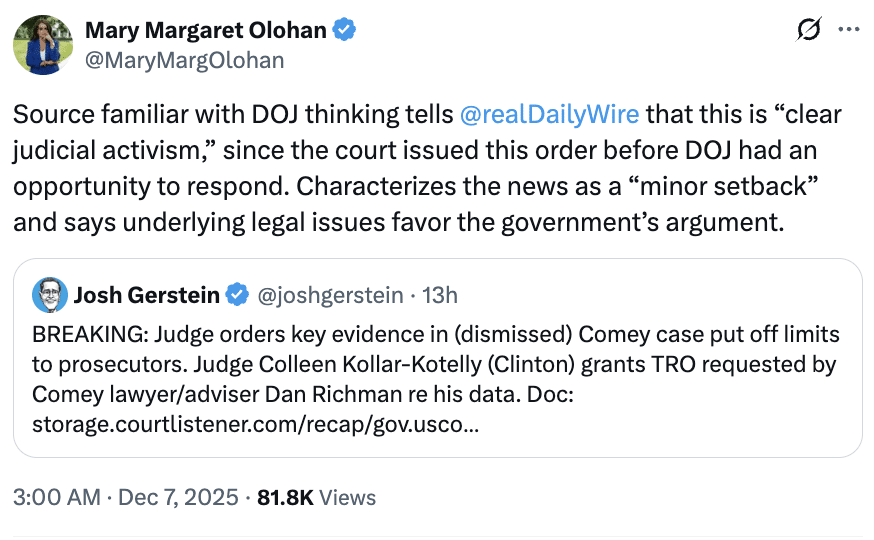

But I think the more interesting development — filed close to the time of the notice of appeals (the notices landed in my email box around 5:44-46PM ET on the last Friday before Christmas and the emergency motion landed in my email box around 5:17PM) — was yet another emergency motion in the Dan Richman case, something DOJ (under Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer’s name) keeps doing. After Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly issued her ruling that sort of said DOJ had to return Dan Richman’s stuff and move the remaining copy to EDVA, DOJ filed an emergency motion asking for clarification and an extension and (in a footnote) reconsideration. After Kollar-Kotelly granted the extension and some clarification (while grumbling about the tardiness and largely blowing off the motion for reconsideration), DOJ asked for another extension. Then DOJ filed a motion just informing Kollar-Kotelly they were going to do something else, the judge issued a long docket order noting (in part) that DOJ had violated their assurances they wouldn’t make any copies of this material, then ordering Richman to explain whether he was cool with this material ending up someplace still in DOJ custody rather than EDVA.

In its December 12, 2025, Order, the Court ordered the Government to “return to Petitioner Richman all copies of the covered materials, except for the single copy that the Court [] allowed to be deposited, under seal, with the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.” See Dkt. No. 20. The Court ordered the Government to certify compliance with its Order by 4:00 p.m. ET on December 15, 2025. Id. The Court further ordered that, until the Government certified compliance with its December 12 Order, the Government was “not to… share, disseminate, or disclose the covered materials to any person, without first seeking and obtaining leave of this Court.” See Order, Dkt. No. 20 at 2 (incorporating the terms of Order, Dkt. No. 10).

On December 15 (the Government’s original deadline to certify compliance with the Court’s December 12 Order), the Government requested a seven-day extension of its deadline to certify compliance with the Court’s December 12 Order. Dkt. No. 22. Petitioner Richman consented to this extension. Id. And the Government represented that it would “continue to comply with its obligation… not to access or share the covered materials without leave of the Court.” Id. at 11 (citing Order, Dkt. No. 10 and Order, Dkt. No. 20). So the Court granted the Government’s request for extension, thereby continuing the Government’s deadline to certify compliance with the Court’s December 12 Order to 4:00 p.m. ET on December 22. Order, Dkt. No. 26.

As of this date, the Government has not certified compliance with the Court’s December 12 Order. Accordingly, the Government is still under a Court order that prohibits it from accessing Petitioner Richman’s covered materials or sharing, disseminating, or disclosing Petitioner Richman’s covered materials to any person without first seeking and obtaining leave of this Court. See Dkt. No. 10; Dkt. No. 20; Dkt. No. 22; Dkt. No. 26. As the Government admits, the Government provided this copy of Petitioner Richman’s materials to the CISO “after the Government filed its emergency motion,” Gov’t’s Mot., Dkt. No. 31 at 1, fn. 1, in which the Government represented that it would “continue to comply with its obligation… not to access or share the covered materials without leave of the Court.” Dkt. No. 22 at 11.

In last night’s motion for emergency clarification (which had all the clarity of something written after a Christmas happy hour), DOJ explained that they couldn’t deposit the materials (which according to Kollar-Kotelly’s orders, would no longer have the single up-classified memo that Richman first shared his entire computer so FBI could get eight years ago) because there was no Classified Information Security Officer in the courthouse serving DOD, CIA, and ODNI. So they raised new complaints — basically, yet another motion for reconsideration. After having claimed, last week, that they had just a single copy of Richman’s data, they noted that actually they had it in a bunch of places, then pretended to be confused about storage devices.

d. The Court further clarified its order on December 16, 2025, stating that the Court “has not ordered the Government to delete or destroy any evidence.” ECF No. 27 at 2. But the Court has also instructed the Government that it may not “retain[] any additional copies of the covered materials.” ECF No. 20 at 2. The government has copies of the information in its systems and on electronic media. It is not clear how the government can avoid “retaining” the materials without deleting them.

e. The Court has not yet otherwise explained whether the Government must provide to Richman the original evidence “obtained in the Arctic Haze investigation (i.e., hard and/or flash drives and discs currently in the custody of the FBI,” ECF No. 22 at 9, some subset thereof (e.g., not including classified information), whether the Government must provide Richman the covered materials in some other fashion, and what else the Government must do (or not do) to comply with the December 12, 2025 order.

After they confessed, last week, that neither the discontinued e-Discovery software nor the now-retired and possibly impaired FBI agent could reconstruct what happened with Richman’s data five years ago, they insisted they were really keeping track of the data, Pinky Promise.

f. Notwithstanding the passage of time, changes in personnel, and the limits of institutional memory, the Government emphasizes that the materials at issue have at all times remained subject to the Department of Justice’s standard evidence-preservation, record-retention, and chain of custody protocols. The Government is not aware of any destruction, alteration or loss of original evidence seized pursuant to valid court-authorized warrants. Any uncertainty reflected in the Government’s present responses regarding the existence or accessibility of certain filtered or derivative working files does not undermine the integrity, completeness, or continued preservation of the original materials lawfully obtained and retained. The Government’s responses are offered to assist the Court in tailoring any appropriate relief under Rule 41(g) in a manner consistent with its equitable purpose, while preserving the Government’s lawful interests and constitutional responsibilities with respect to evidence obtained pursuant to valid warrants and subject to independent preservation obligations.

Every single thing about the treatment of Richman’s data defies this claim, which is why he had a Fourth Amendment injury to be redressed in the first place.

Nevertheless, in this their second motion fashioned as a motion for clarification, they they propose, can’t we just keep all the data and Pinky Promise not to do anything with it?

g. Rather than require the government to “return” or otherwise divest its systems of the information, the government respectfully suggests that the more appropriate remedy would simply be to direct the government to continue not to access the information in its possession without obtaining a new search warrant. It is not clear what Fourth Amendment interest would be served by ordering the “return” of copies of information (other than classified information) that is already in the movant’s possession, and that the government continues to possess, at least in the custody of a court (or the Department of Justice’s Litigation Security group, as may be appropriate given the presence of classified information). And the Court’s order properly recognizes that it is appropriate for the government to retain the ability to access the materials for future investigative purposes if a search warrant is obtained. ECF No. 20 at 1. Forcing transfer of evidentiary custody from the Executive Branch to the Judiciary would depart from the traditional operation of Rule 41(g), which is remedial rather than supervisory, and would raise substantial separation-of-powers concerns. The government respectfully suggests that the best way to do that is to allow the executive branch of government to maintain the information in its possession, rather than forcing transfer of evidence to (and participation in the chain of custody by) a court. See, e.g., United States v. Bein, 214 F.3d 408, 415 (3d Cir. 2000) (applying then-Rule 41(e) and noting that it provided for “one specific remedy—the return of property”); see also Peloro v. United States, 488 F.3d 163, 177 (7th Cir. 2007) (same regarding now-Rule 41(g)).

Having violated their promise not to make copies without permission once already, they Pinky Promised, again, they wouldn’t do so.

b. The Government shall continue not to access or share the covered materials without leave of the Court. See ECF No. 10 at 4; ECF No. 20 at 2.

And then they offered a horseshit excuse to ask for a two week extension beyond the time Kollar-Kotelly responds to their latest demands (partly arising from their own stalling of this matter into Christmas season) — that is, not a two week extension from yesterday, which would bring them to January 2, but instead two weeks from some date after December 22, which was at the time Richman’s next deadline.

a. Because it is yet not clear to the Government precisely what property must be provided to Richman by December 22, 2025 at 4:00 PM (and what other actions the Government must or must not take to certify compliance with the December 12, 2025 order as modified), the Government respectfully requests that it be provided an additional fourteen days (because of potential technological limitations in copying voluminous digital data and potential personnel constraints resulting from the upcoming Christmas holiday) from the date of the Court’s final order clarifying the December 6, 2025 order to certify compliance. 1

1 An extension of the compliance deadline is merited by the extraordinary time pressure to which the Government has been subjected and the necessity of determining, with clarity, what the Government must do to comply with the December 12, 2025 order as clarified and modified. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(6); see also ECF No. 22 at 6–7 (summarizing applicable legal principles). [my emphasis]

They asked, effectively, to stall compliance for a month.

As a reminder, the grand jury teed up before Aileen Cannon convenes on January 12.

Kollar-Kotelly’s response (which landed in my email box at 7:06, so definitely after prime Christmas happy hour time) was … weird. In addition to granting the government part of the extension they requested (until December 29), she all of a sudden asked Richman what happened after he voluntarily let the FBI image his computer so they could ensure there was no classified information in it.

At present, in this second request, the Court would benefit from additional detail from Petitioner Richman regarding the Government’s imaging of Petitioner Richman’s personal computer hard drive in 2017. In 2017, Petitioner Richman consented to have the Government seize his personal computer hard drive, make a copy (an “image”) of his personal computer hard drive, and search his personal computer hard drive for the limited purpose of identifying and deleting a small subset of specified material. The Court is requesting information as to whether the hard drive that Petitioner Richman consented to have imaged by the Government was ever returned to Petitioner Richman, and, if so, whether any of the specified material had been removed from the hard drive that was returned.

Now maybe she’s asking this question simply to refute DOJ’s claim that any material independently held has to be held by a CISO.

The answer to this question is publicly available in the 80-page IG Report on this topic.

On June 13, 2017, FBI agents went to Richman’s home in New York to remove his desktop computer. On June 22, 2017, FBI agents returned the desktop computer to Richman at his home in New York after taking steps to permanently remove the Memos from it. While at Richman’s residence on June 22, 2017, the FBI agents also assisted Richman in deleting the text message with the photographs of Memo 4 from his cell phone.

It’s not clear why they ever kept the image in the first place (remember, they didn’t obtain a warrant to access it until well over two years later).

But I worry that Kollar-Kotelly is getting distracted from the clear recklessness — including DOJ’s most recent defiance of her order and their own Pinky Promises — for which Richman is due a remedy by the distinction between his physical property (the hard drive he got back eight years ago) and his digital property (the image of that hard drive, his Columbia emails, his iCloud, his iPhone, and iPad). The most serious abuse of his Fourth Amendment rights involved his phone, which DOJ only ever had in digital form, regardless of what kind of storage device they stored that content on (which we know to be a Blu-ray disc).

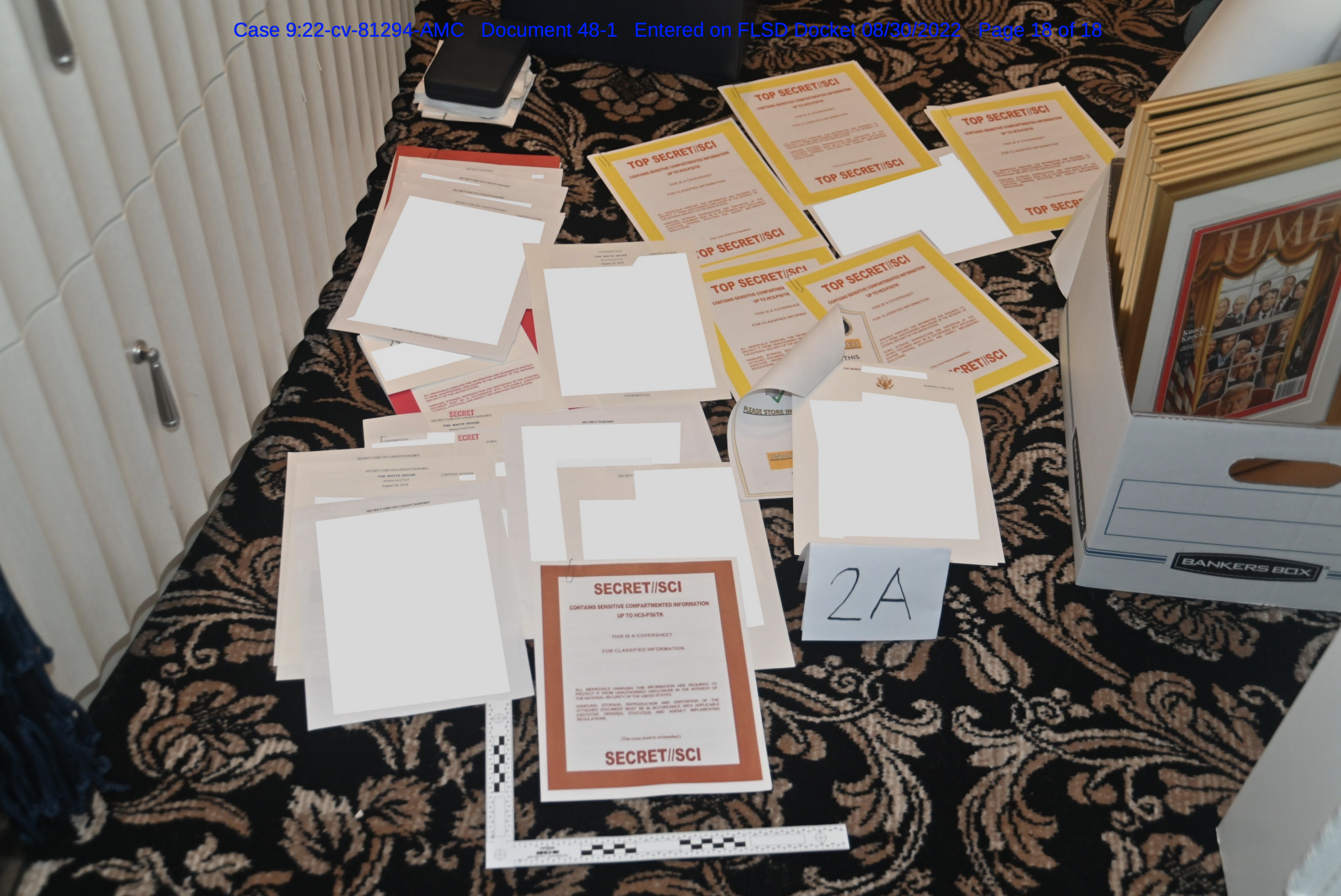

And meanwhile, everything about the government’s actions suggest they’re going to string Kollar-Kotelly along until they can get a warrant from the judge, Cannon, who once said Trump had to be given boxes and boxes of highly classified documents back because they also contained a single letter written by Trump’s personal physician and another letter published in Mueller materials.

They are just dicking around, at this point.

There’s a lot of shit going down in documents signed (as this emergency motion is) with Todd Blanche’s name. He still seems to believe he can juggle his way through politicizing the Department of Justice with some carefully executed Friday Night document dumps.