“Shitshow:” Greg Bovino’s Zero Success Rate

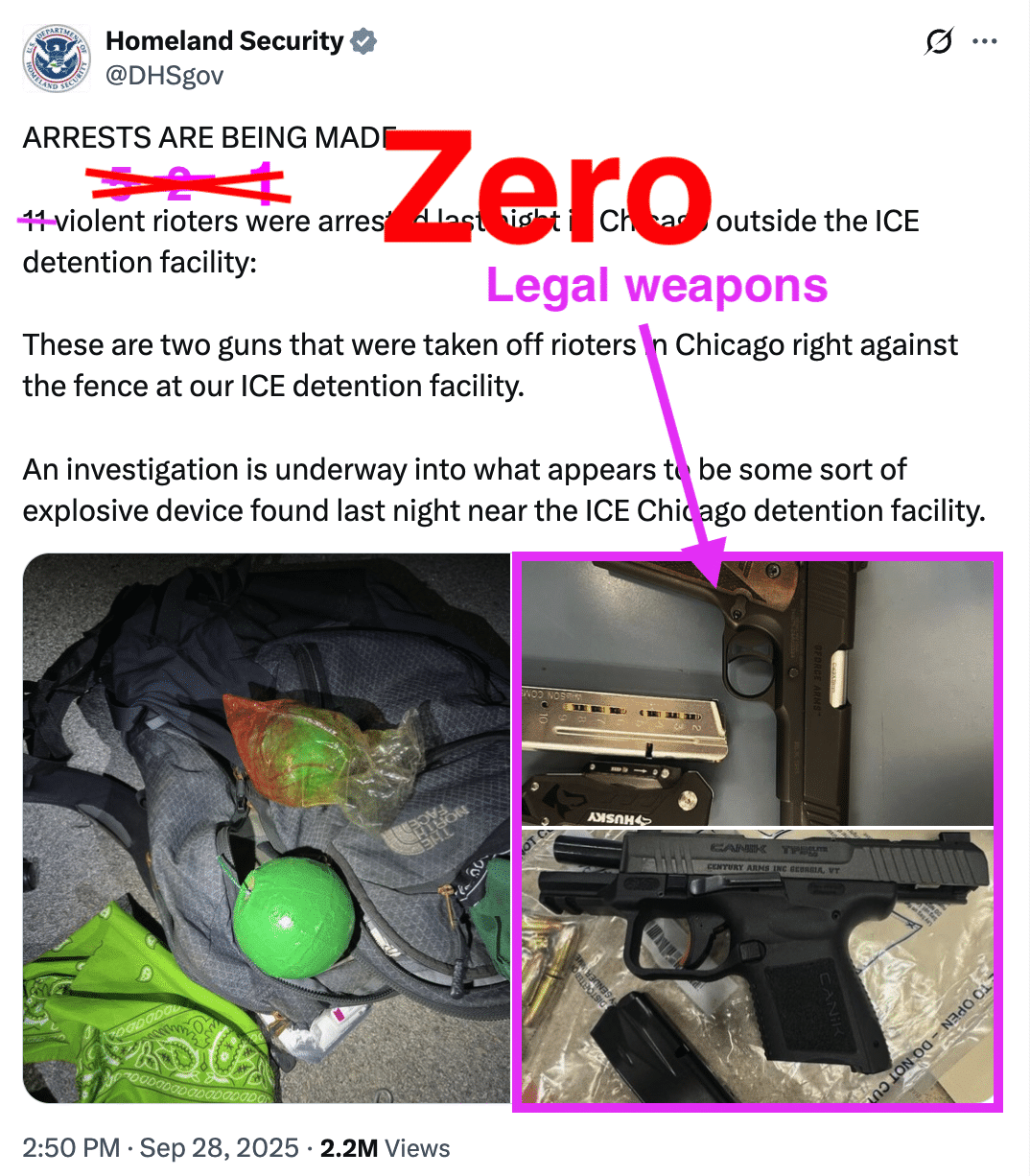

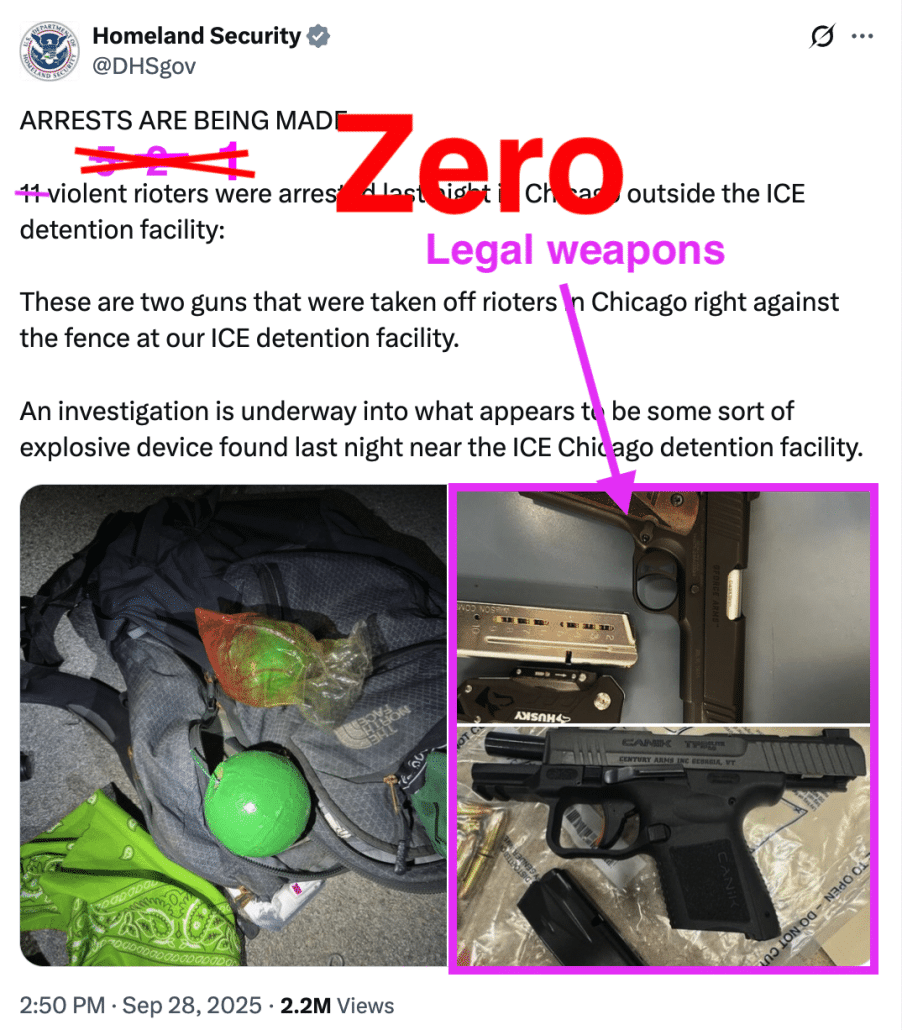

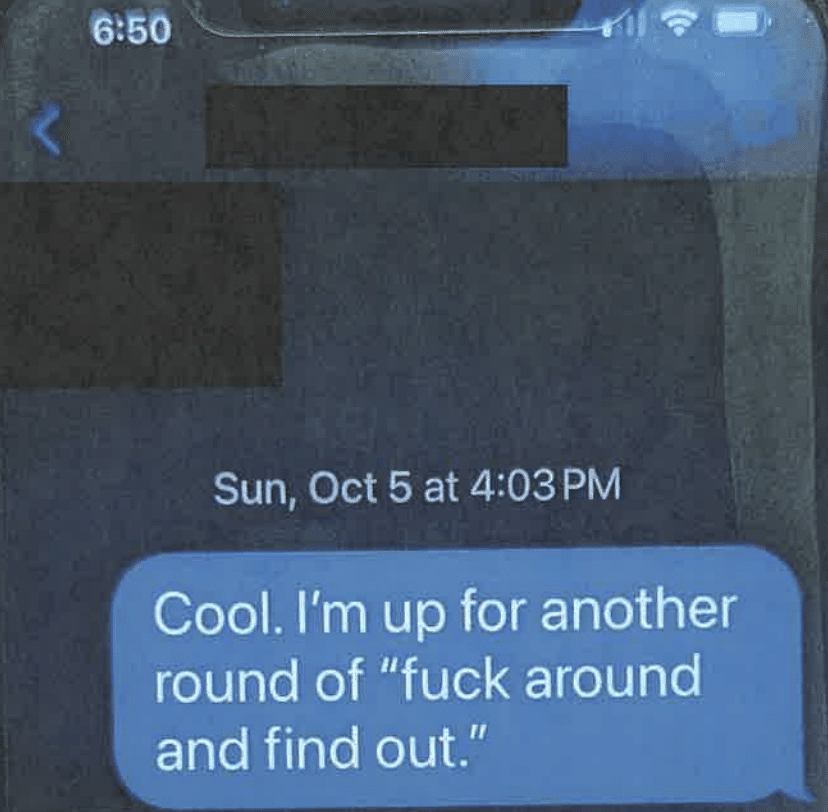

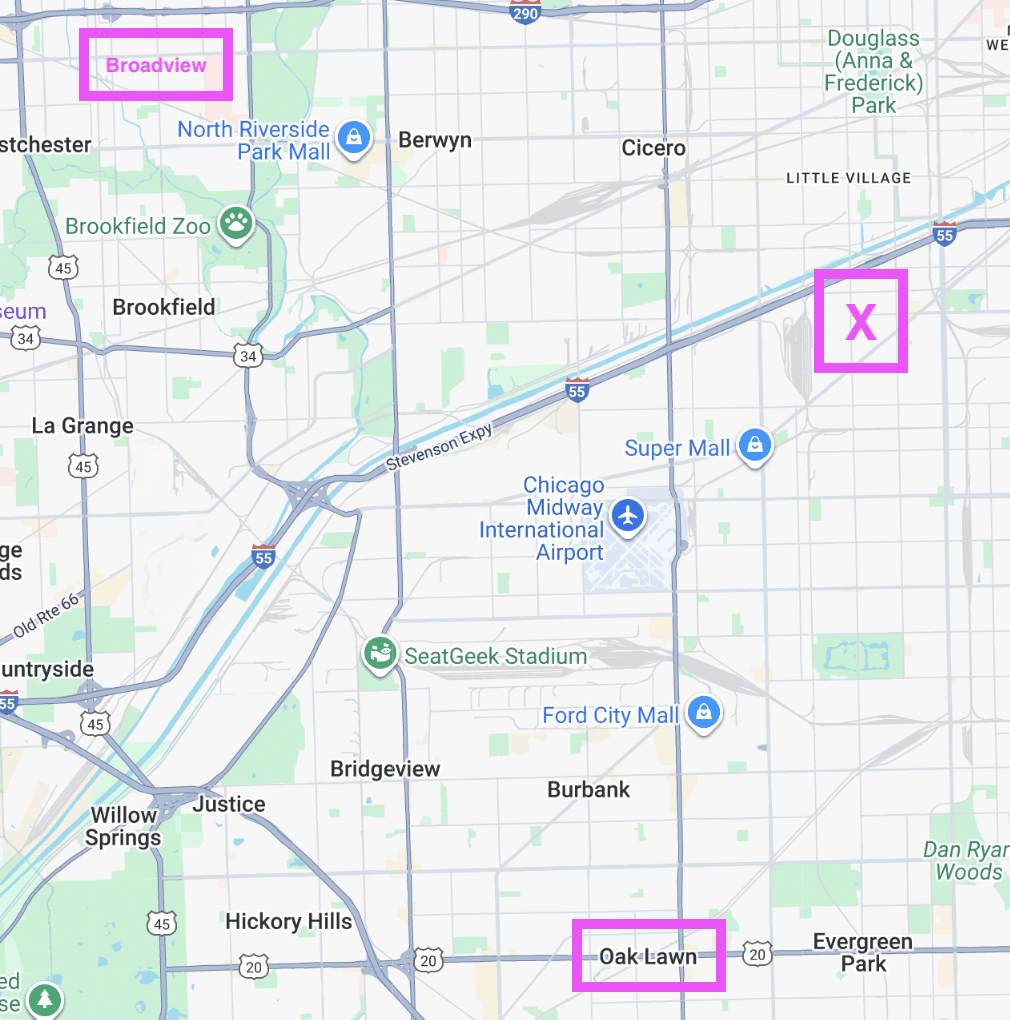

Back on October 8, I noted that of the eleven people DHS claimed had been arrested at a September 27 protest at the Broadview ICE facility in Chicago, a protest at which Greg Bovino had promised a “shitshow,” the cases of all but one had been dismissed.

Bovino, I noted, was batting just 9% on his claims that protestors had engaged in violence.

Well, yesterday, the case of Dana Briggs, a 70-year old Air Force veteran charged with assault when he fell as officers were pushing him back, was dismissed too. He had planned to call Bovino as a witness at his December trial. Bovino’s success rate at substantiating his claim there were any rioters from that day is now zero.

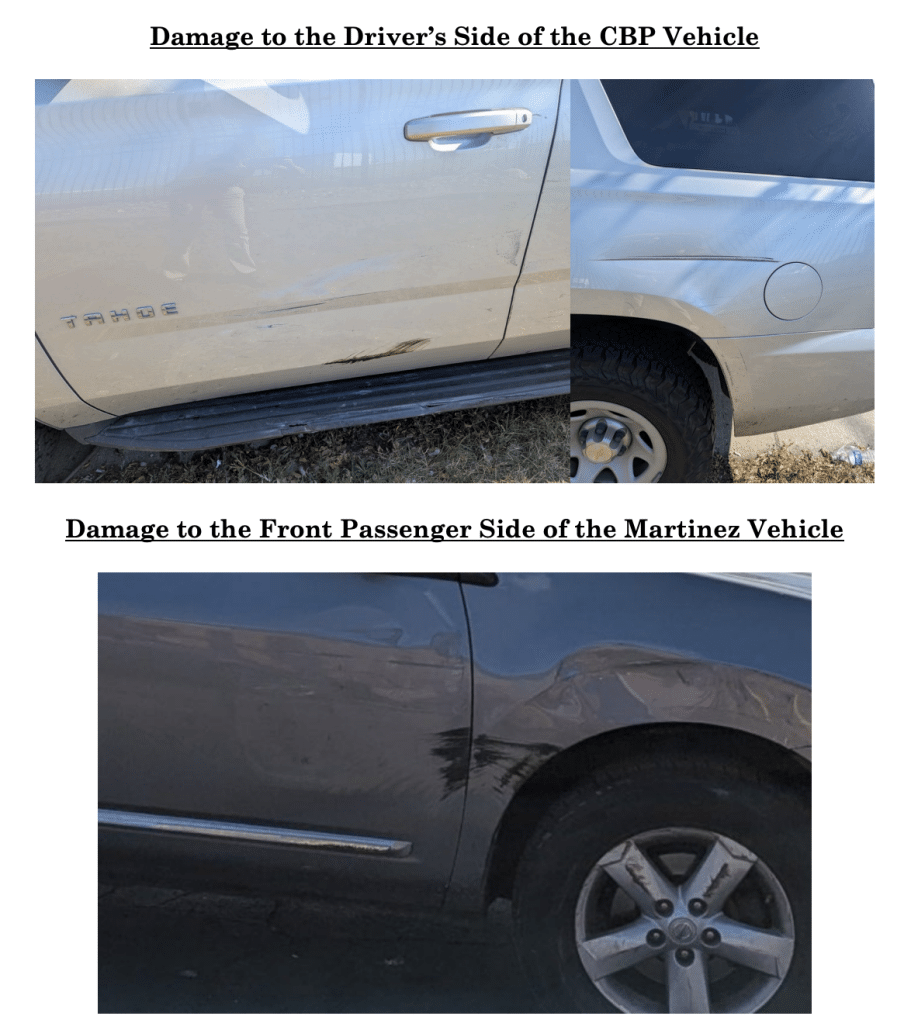

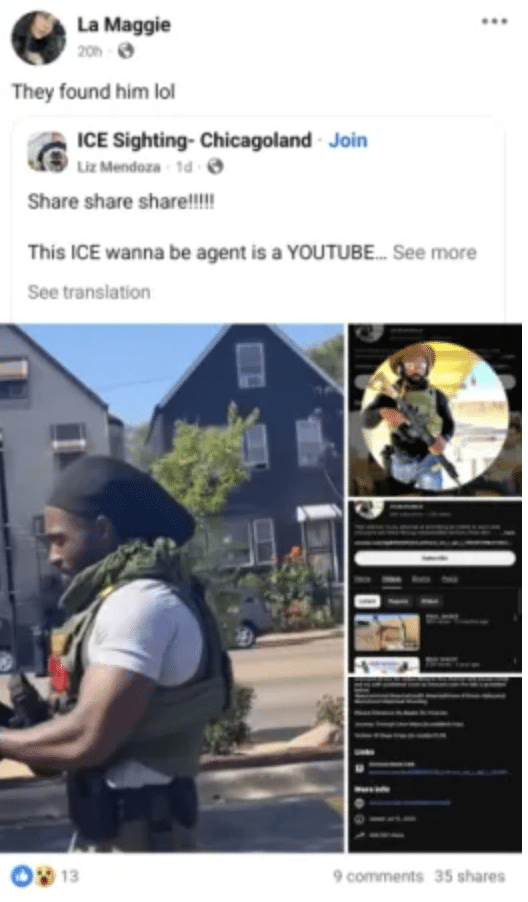

Briggs is not actually the most stunning dismissal from yesterday. The case against Marimar Martinez (and her co-defendant Anthony Ruiz) was also dismissed, just before a follow-up hearing on the things the CBP agent, Charles Exum, did and said before and after he shot her.

At a press hearing afterward, Martinez’ attorney Christopher Parente suggested they would still be seeking vindication for her, so hopefully we’ll still get to learn what DOJ dropped the case in hopes of suppressing.

The Magistrate Judge who dismissed Briggs case (who had also signed the arrest warrants for the five actual arrests on September 27), Gabriel Fuentes, wrote a long opinion about the collapse of the September 27 cases.

Examining more closely the five September 27 Broadview criminal arrest cases, all of which came before the undersigned magistrate judge, the Court notes the following facts:

1) The initial complaints charged four (Collins, Robledo, Ivery, and Briggs) of the foregoing five persons with felony violations of Section 111(a). Only the complaint against Mazur was filed as a misdemeanor.

2) With today’s dismissal of the Briggs criminal information, none of these cases remains pending today – all have been dismissed.

3) As the docket entries reflect in all five of the cases, the undersigned magistrate judge obtained a sworn statement from the affiants in each affidavit, at the time of complaint issuance, that not only were the affidavit allegations true, but that video evidence of the encounters existed, that the affiants had reviewed the video evidence, and that the video evidence corroborated the version of events set forth in the affidavits. Mazur (D.E. 11); Collins/Robledo (D.E. 26); Ivery (D.E. 13); and Briggs (D.E. 14).

[snip]

4) Each of the five persons arrested on September 27 from Broadview on Section 111 charges endured official detention (or other government restrictions on their liberty) after their arrests.

[snip]

Importantly, nothing in this order should be construed as scolding the government for dismissing in these cases. Dismissing appears to be the responsible thing for the government to have done, in light of the government’s judgment and discretion. But the Court cannot help but note just how unusual and possibly unprecedented it is for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in this district to charge so hastily that it either could not obtain the indictment in the grand jury or was forced to dismiss upon a conclusion that the case is not provable, in repeated cases of a similar nature. Federal arrest brings federal detention, even for a short time. It brings the need to obtain counsel, to appear at court hearings, to answer the charges (as Briggs did in this case, pleading not guilty), and to prepare for trial (as Briggs also has had to do in this case). Being charged with a federal felony, even if it is later reduced to a misdemeanor, is no walk in the park.

He also noted, repeatedly, that Briggs’ case was dismissed when he noticed his intent to call Bovino to testify.

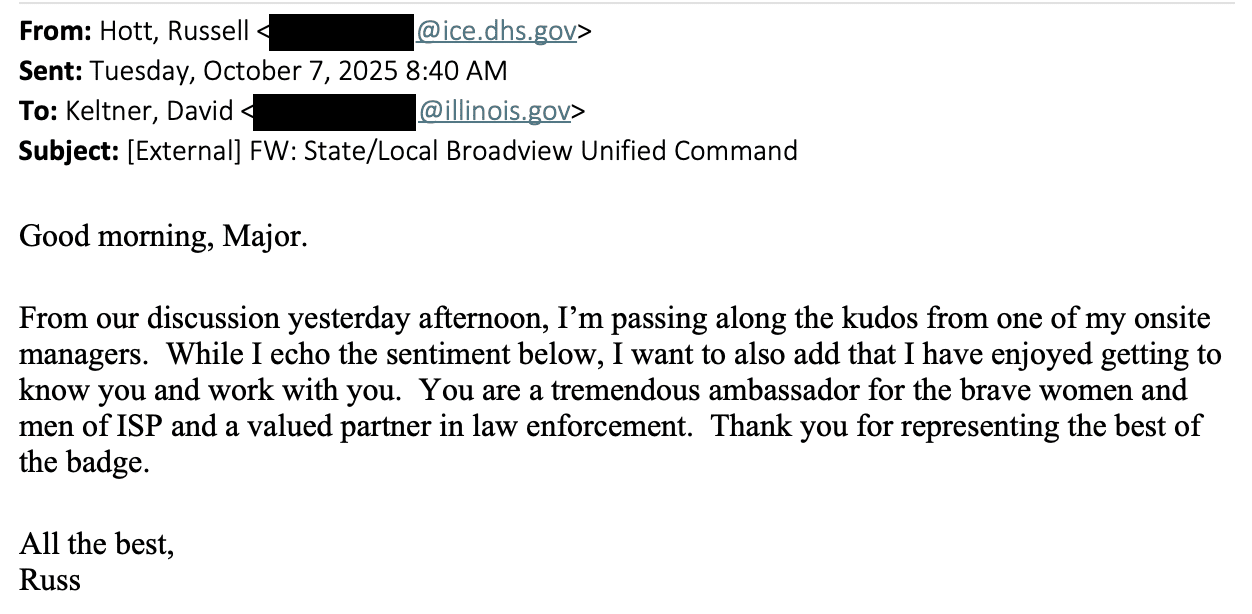

Also yesterday, Judge Sara Ellis released her 233-page opinion in the Civil Rights case against the ICE/CBP invasion (my weekend reading, I guess), which catalogs the depredations done during that invasion, including her judgement that Bovino is a liar.

Turning to Bovino, the Court specifically finds his testimony not credible. Bovino appeared evasive over the three days of his deposition, either providing “cute” responses to Plaintiffs’ counsel’s questions or outright lying. When shown a video of agents hitting Rev. Black with pepper balls, Bovino denied seeing a projectile hit Rev. Black in the head. Doc. 191- 3 at 162:21–165:17; Doc. 22-44 (Ex. 44 at 0:10–12, available at https://spaces.hightail.com/space/ZzXNsei63k). In another video shown to Bovino, he obviously tackles Scott Blackburn, one of Plaintiffs’ declarants. Doc. 191-3 at 172:13–173:7; Doc. 22-45 (Ex. 45 at 0:19–30, available at https://spaces.hightail.com/space/ZzXNsei63k). But instead of admitting to using force against Blackburn, Bovino denied it and instead stated that force was used against him. Doc. 191-3 at 173:9–176:11, 179:11–181:5. Bovino also testified that, in Little Village on October 23, 2025, several individuals associated with the Latin Kings were found taking weapons out of the back of their car, and that they, as well as at least one individual on a rooftop and one person in the crowd of protesters, all wore maroon hoodies. Id. at 227:2– 228:21. He further testified that he believed the “maroon hoodies . . . would signify a potential assailant or street gang member that was making their way to the location that I was present” and that “there did begin to appear, in that crowd, maroon hoodies, both on top of buildings and in the crowd.” Doc. 237 at 18:22–19:10. But Bovino also admitted that he could not identify a street gang associated with the color maroon, id. at 19:11–13, although Hewson acknowledged that while Latin Kings members usually wear black, “they also can throw on maroon hoodies,” Doc. 255 at 264:17–20.10 Even were maroon hoodies to signify gang membership, the only evidence on footage from the relevant date of individuals dressed in maroon protesting in Little Village consists of a male wearing a maroonish jacket with an orange safety vest over it, Alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez wearing a maroon sweater with a suit jacket over it, a female in a maroon shirt, a female in a maroon sweatshirt, and a man with a maroon hoodie under a green shirt and vest. Axon_Body_4_Video_2025-10-23_1053_D01A38302 at 10:03–10:33; Axon_Body_4_Video_2025-10-23_1106_D01A32103 at 16:12–17:17. Bovino’s and Hewson’s explanations about individuals in maroon hoodies being associated with the Latin Kings and threats strains credulity.

Most tellingly, Bovino admitted in his deposition that he lied multiple times about the events that occurred in Little Village that prompted him to throw tear gas at protesters. As discussed further below, Bovino and DHS have represented that a rock hit Bovino in the helmet before he threw tear gas. See Doc. 190-1 at 1; Homeland Security (@DHSgov), X (Oct. 28, 2025 9:56 a.m.), https://x.com/dhsgov/status/1983186057798545573?s=46&t=4rUXTBt_W24muWR74DQ5A. Bovino was asked about this during his deposition, which took place over three days. On the first day, Bovino admitted that he was not hit with a rock until after he had deployed tear gas. Doc. 191-3 at 222:24–223:18. Bovino then offered a new justification for his use of chemical munitions, testifying that he only threw tear gas after he “had received a projectile, a rock,” which “almost hit” him. Doc. 191-3 at 222:24–223:18. Despite being presented with video evidence that did not show a rock thrown at him before he launched the first tear gas canister, Bovino nonetheless maintained his testimony throughout the first and second days of his deposition, id. at 225–27; Doc. 237 at 11–17. But on November 4, 2025, the final session of his deposition, Bovino admitted that he was again “mistaken” and that no rock was thrown at him before he deployed the first tear gas canister. Doc. 238 at 9:12–21 (“That white rock was . . . thrown at me, but that was after . . . I deployed less lethal means in chemical munitions.”); id. at 10:20–23 (Q. [Y]ou deployed the canisters, plural, before that black rock came along and you say hit you in the head, correct? A. Yes. Before the rock hit me in the head, yes.”).

This is what the complete collapse of credibility looks like.

It should have happened after Bovino got caught prevaricating on the stand in Brayan Ramos-Brito’s Los Angeles trial in September, another protestor charged with assault but ultimately exonerated.

But unless and until an Appeals Court disrupts Ellis’ finding (the Seventh Circuit has stayed her order with respect to remedy, not fact-finding), the word of Greg Bovino will be utterly useless in any court in the United States.

Greg Bovino and his violent goons have moved on, at least to Charlotte (where — as Chris Geidner laid out — Bovino doesn’t understand he’s the guy trying to kill Wilbur, not the clever spider who thwarts that effort), possibly already onto New Orleans.

But his reputation as a liar will now follow him wherever he goes.