Reflections on The Deficit Myth

Posts in this series

The Deficit Myth By Stephanie Kelton: Introduction And Index

Debunking The Deficit Myth

MMT On Inflation

The first three posts in this series address the Introduction and the first two chapters of Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth. In this post I add her definition of money and some of my thoughts, and invite readers to do the same, either questioning points she made or applying her ideas to our society.

1. Modern Monetary Theory starts by asking one question: how does money work in a fiat currency nation. Kelton defines money in her first published paper: The Hierarchy of Money. This is a very readable discussion of the range of opinions on this subject, focused on the argument between the Metalists and the Chartalists, which began over 400 years ago. [1] Kelton starts with a definition of money. [2]

Money represents a debt-relation or promise to pay that exists between human beings. It cannot be identified independently of its institutional usages, because money represents a social relationship. … The creation of money, then, is simply the balance sheet operation that records this social relation. (Emphasis in original.)

According to Kelton, the Chartalists called money any token representing a debt relationship. Thus, a postal stamp is a money: it represents an asset to the owner and a debt to the Post Office which is satisfied by delivering a letter. A plane ticket is money: it represents the obligation of the airline to fly the holder to a particular place at a particular time. Bank deposits are money: they are a liability of the bank which must deliver money at the direction of the account holder. The rule for creation of money is the agreement by one person to hold the debt of another. [2]

Now consider the dollar. The dollar is a creation of the federal government. Kelton writes:

Thus, State money is created when the public agrees to hold (as an asset) state-created money (a liability to the State) which is required in payment of taxes.

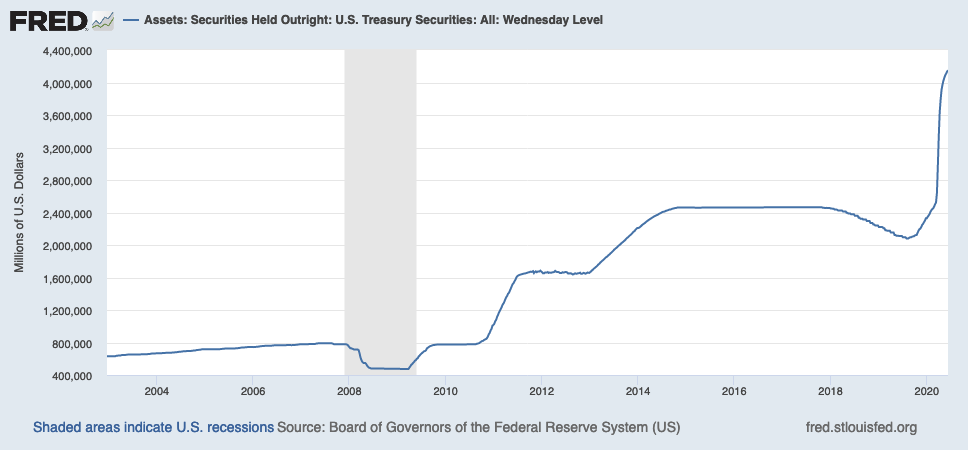

This explains why currency and other forms of dollars (bank deposits, treasury securities, and bank reserves at the Fed) are liabilities of the federal government. We users agree to hold these dollars as assets. We can use them to acquire different forms of assets from sellers, obtain services from providers, and pay taxes. When the government collects taxes, it matches that asset with a corresponding liability and clears to zero.

The point of this exercise is to demonstrate that money is a balance sheet representation of the debt/asset relations between human beings, a social relationship. That understanding is crucial to the arguments advanced in The Deficit Myth.

2. Kelton calls for a Copernican Revolution in the way we think about money. This, of course, is a reference to the Copernican Theory, which said that the earth revolves around the Sun, and not vice versa, despite what we see with our own eyes. The ramifications of the Copernican Revolution eventually led to a complete change in our understanding of the nature of reality. [3] The revolutionary change she describes is that US government spending is not constrained by its ability to tax and borrow, but by the actual resources available, labor, material, and the organization of production. One important part of The Deficit Myth is the description of the kinds of changes we have to make in our own thinking. But there are many more revolutions. Here are three.

a. Congress ducks policy arguments by turning them into discussions of budgets or into political games. That never made sense, because all budgeting is about priorities. Games like pay-fors or one-upmanship on military spending were always perverse, but both parties pretended these were real arguments. They aren’t. MMT strips away one more layer of pretense.

b. Mainstream economists refuse to look honestly at MMT. Marion Fourcade and her colleagues at Berkeley published a paper examining the economics profession titled The Superiority of Economists, a devastating critique of their pretensions. Among other things, economists tell us that markets should make our decisions about allocation of resources, and that anything that interferes with the operations of markets is harmful to society. When government spending is between 35 and 45% of GNP prior to the pandemic, it’s stupid to argue that markets are the best form of allocation of resources. When capitalists exercise outlandish control of government spending priorities, it’s stupid to argue that markets should determine what we can and can’t have.

Many economists hold themselves out as experts on all sorts of things, including the pandemic. In the MMT world, as Kelton points out, economists would concentrate on predicting the inflationary effect of spending choices, and get completely out of the business of telling us how we should make decisions about allocation of resources.

c. Historically, people thought that the most important problem facing an economy was to accumulate capital and turn it to productive use for the benefit of society. The chosen solution was Capitalism, and to encourage capitalists to invest, we allowed them to reap outlandish profits through monopoly, grants from the Crown, and other favors, while ignoring the fraud and corruption those policies entailed. This continued in the US, with gigantic giveaways to railroad and mining companies, ludicrous levels of patent protection, and grotesquely unfair tax rules, while mostly ignoring or even praising graft, corruption and fraud. The results of coddling capitalists are rubbed in our faces every day.

MMT gives us space to think about the way society could operate to make our lives better. It allows us to make decisions about what we need and want. We do not have to accept whatever is on offer from Capitalists. We can decide based on our principles, morals, values and dreams. MMT puts us in charge, and frees us from the domination of the rich. It opens the door to the “euthanasia of the rentier”, as Keynes calls it in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

Now, though this state of affairs would be quite compatible with some measure of individualism, yet it would mean the euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity-value of capital.

=====

[Graphic via Grand Rapids Community Media Center under Creative Commons license-Attribution, No Derivatives]

[1] Fun fact, Adam Smith may have held Chartalist views. Kelton quotes him thus:

A prince, who should enact that a certain proportion of his taxes should be paid in a paper money of a certain kind, might thereby give a certain value to this paper money.

[2] Kelton doesn’t go into the history of money, but this BBC article is a fascinating picture of trade in Ancient Sumeria, and gives a tantalizing hint about the origin of money in record-keeping and accounting for trade.

[3] For a fascinating and occasionally comprehensible discussion of this new understanding, see Reality Is Not What It Seems, by Carlo Rovelli.