The New Russian Hack Sanctions

The Treasury Department issued new Russian sanctions today, partly fulfilling the congressionally-mandated requirement it do so, but also adding to the retaliatory sanctions President Obama imposed in December 2016. Effectively, this applied the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act of 2017 (CAATSA) sanctions ordered by Congress to the Russian spooks (but not the private hackers) Obama sanctioned, and applies the Obama EO-based sanctions to the Russians and companies listed in the Internet Research Agency indictment.

The breadth of accused activities

Given the limited number of people actually newly sanctioned (and the symbolic nature of sanctions imposed on people who are unlikely to travel to or have money in the US), this may be just Steve Mnuchin’s effort to buy time for the Administration; the Treasury press release even includes a promise for more CAATSA sanctions at a later date.

“The Administration is confronting and countering malign Russian cyber activity, including their attempted interference in U.S. elections, destructive cyber-attacks, and intrusions targeting critical infrastructure,” said Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin. “These targeted sanctions are a part of a broader effort to address the ongoing nefarious attacks emanating from Russia. Treasury intends to impose additional CAATSA sanctions, informed by our intelligence community, to hold Russian government officials and oligarchs accountable for their destabilizing activities by severing their access to the U.S. financial system.”

That said, the press release for the sanctions is rather interesting in the breadth of activities these sanctions are said to be retaliation for. It includes the election hack, the NotPetya attack recently attributed to GRU (the rough equivalent to DIA) by the UK and US, and ongoing attacks on American critical infrastructure. (DHS and FBI issued a report on the latter.)

Today’s action counters Russia’s continuing destabilizing activities, ranging from interference in the 2016 U.S. election to conducting destructive cyber-attacks, including the NotPetya attack, a cyber-attack attributed to the Russian military on February 15, 2018 in statements released by the White House and the British Government. This cyber-attack was the most destructive and costly cyber-attack in history. The attack resulted in billions of dollars in damage across Europe, Asia, and the United States, and significantly disrupted global shipping, trade, and the production of medicines. Additionally, several hospitals in the United States were unable to create electronic records for more than a week.

Since at least March 2016, Russian government cyber actors have also targeted U.S. government entities and multiple U.S. critical infrastructure sectors, including the energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation, and critical manufacturing sectors. Indicators of compromise, and technical details on the tactics, techniques, and procedures, are provided in the recent technical alert issued by the Department of Homeland Security and Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The move happens to come when the White House issued both a formal statement joining European allies in pinning the attempted assassination of former GRU officer Sergei Skripal on Russia and Trump endorsing that view in statements to the press.

FSB not SVR sanctions

In addition to not resanctioning the private individuals named in December 2016, today’s sanctions are interesting in that they continue to blame FSB (a more thuggish equivalent of FBI) alongside GRU for the hack. I described why the inclusion of FSB was interesting here.

But it’s interesting for another reason: recent reporting. Both Dutch reporting on how its intelligence service caught Russian hackers in real time and a recent David Sanger article have instead credited SVR (the rough equivalent of CIA) with the hack. The head of SVR is already sanctioned, but it would seem that if the most up to date intelligence says SVR did the hack, they might be included here.

Two new GRU sanctionees — of the age they might have overlapped with Skripal

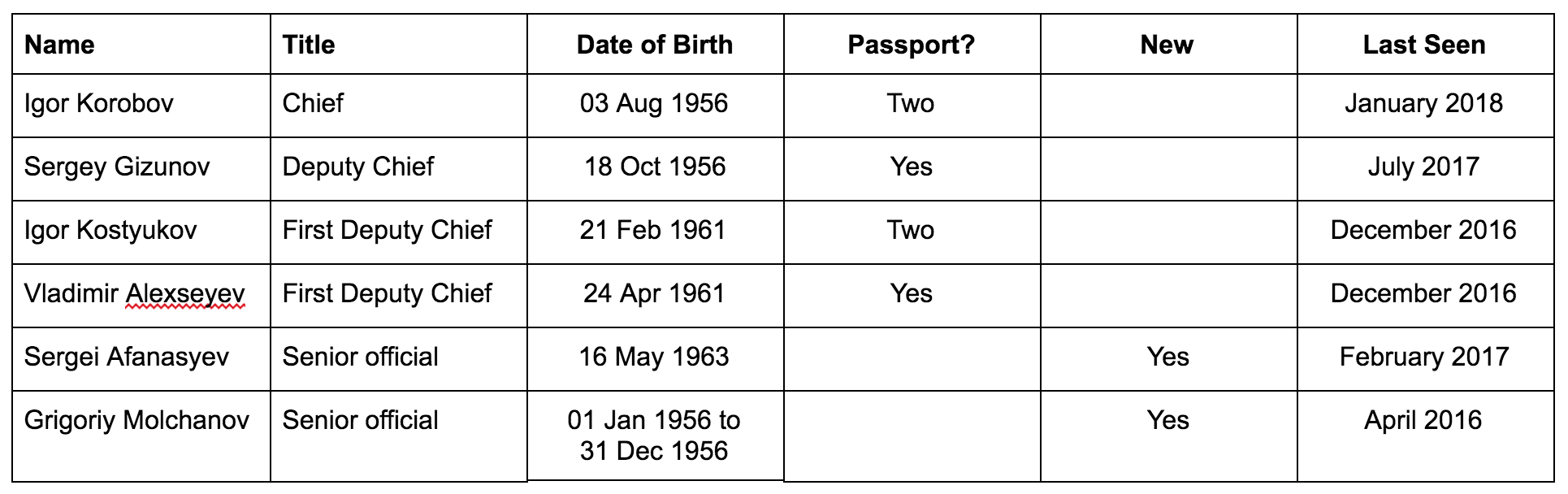

The sanctions also add two new GRU officers described only as senior GRU officers.

AFANASYEV, Sergei (a.k.a. AFANASYEV, Sergey), Russia; DOB 16 May 1963; Gender Male (individual) [CAATSA – RUSSIA] (Linked To: MAIN INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORATE).

MOLCHANOV, Grigoriy Viktorovich; DOB 01 Jan 1956 to 31 Dec 1956; citizen Russia; Gender Male (individual) [CAATSA – RUSSIA] (Linked To: MAIN INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORATE).

At roughly 55 and 62, these guys may have overlapped with Skripal (as would the others, whom the US obviously has more information on).

The last known dates

Perhaps most interesting, however, the Treasury press release description of the targeted GRU officers includes fascinating “as of” dates that would seem to indicate the last time it’s willing to admit we’ve gotten intelligence on these people.

Korobov came to the US in late January (and he’s a public figure that our own intelligence services would coordinate with), so it’s unsurprising his information is the most up-to-date, to that same time.

But we apparently (admit to having) more recent data, dating to last February, on one of the people newly added to this list — Afanasyev — than on the First Deputies originally sanctioned. That precedes the NotPetya activity being sanctioned here.

Most interesting is Molchanov. We not only don’t have passport information for him (though that’s not definitive, as none of the IRA people have passports listed, and we must have passport numbers for the ones that traveled to the US), but we don’t even have a solid date of birth. The “as of” date for him, April 2016, comes before the DNC hack was public, but around the time George Papadopoulos was learning about it. It also comes from before the sanctions in December 2016. Clearly, we’ve learned something about him since then that has won him significantly more focus, even if we don’t know when to send his birthday greetings.

These two new additions are both pretty old to be doing any hacking themselves (indeed, they’re contemporaries of all the top brass). But their addition may suggest we’ve learned more about how GRU’s hacking operates.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)