Pam Bondi Replaces Her Embarrassing Reading Comprehension Failure with a 4A Violation

When Judge Cameron Currie surprised Pam Bondi’s Counselor, Henry Whitaker, on Thursday with a question about whether DOJ believes Aileen Cannon wrongly dismissed Trump’s stolen documents case, Whitaker claimed what distinguished Jack Smith from Lindsey Halligan is that Halligan is closely supervised.

I do think that mostly what was driving Judge Cannon’s decision in that case was sort of the unique and broad authority that the special counsel possessed sort of free of supervision, which, of course, is an element that we do not have here.

He said that, mind you, even while conceding that Pam Bondi had claimed to ratify the Comey indictment even though the transcripts didn’t show how Halligan instructed the grand jury, yet.

MR. WHITAKER: Well, it’s true that — it is true, Your Honor, you’re right, that we didn’t have the intro and back end of the grand jury transcripts when we presented that.

Between that day, on October 31, when Pam Bondi claimed to ratify Lindsey’s work without noticing she couldn’t see that work, and yesterday, several things have happened.

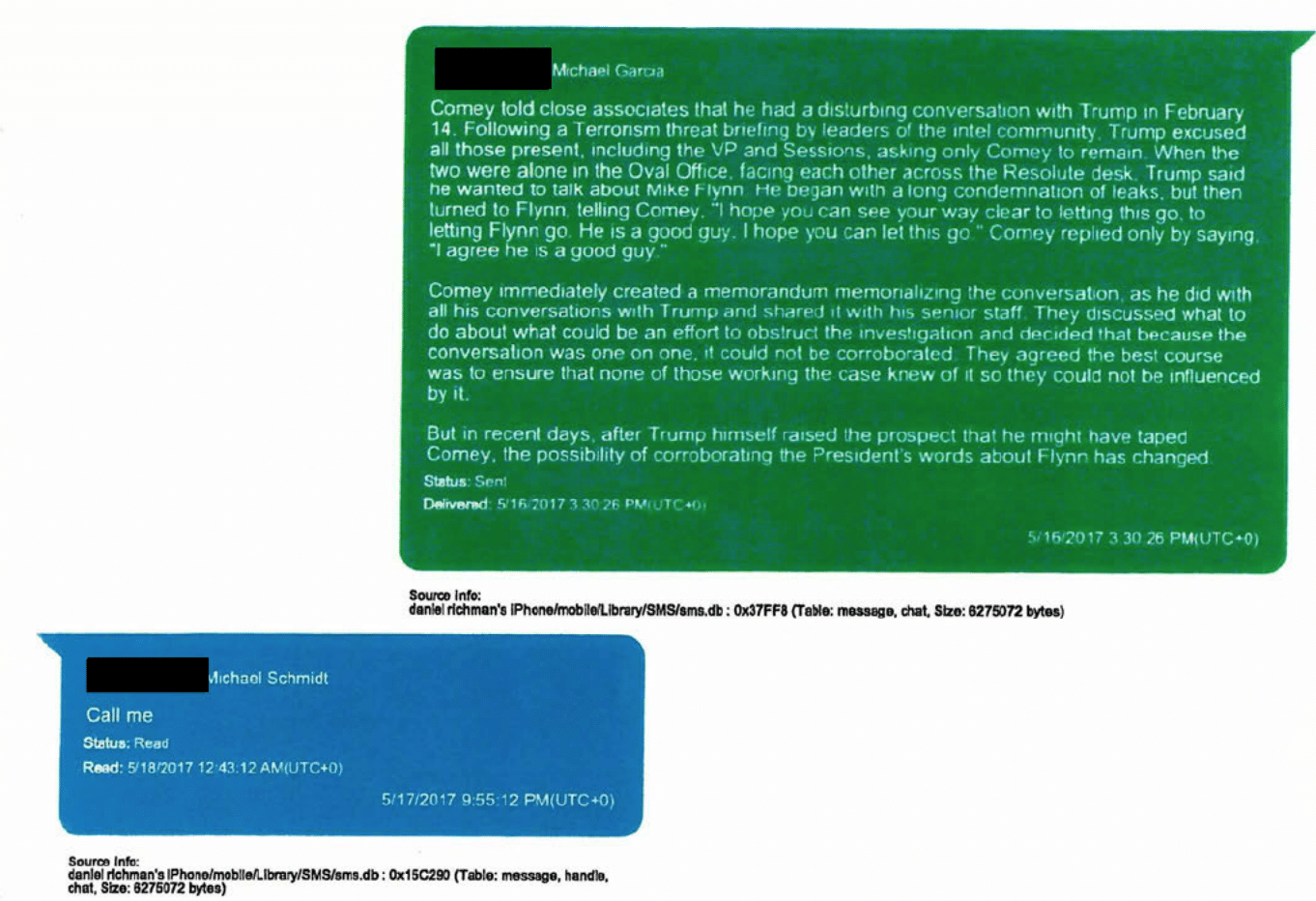

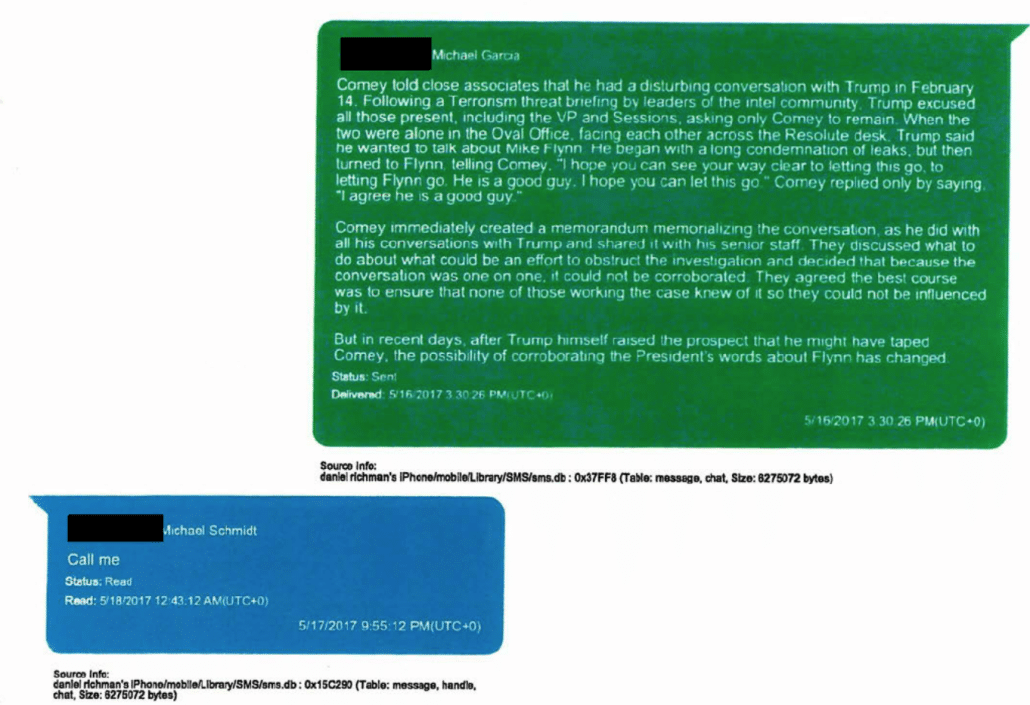

We’ve gotten a lot more details about the suspected Fourth Amendment and Attorney-Client privilege violations Jim Comey’s investigators committed. First, Rebekah Donaleski told Magistrate Judge William Fitzpatrick that Jim Comey’s team believed investigators had worked off material seized from Dan Richman that was not responsive to the four warrants used to investigate him. Effectively, a general warrant.

[D]id the agents preserve nonresponsive copies or nonresponsive materials for five years? Because the Fourth Circuit has said that’s not reasonable. Did that happen? Because the prolonged retention of nonresponsive electronic data can render an initially lawful search unconstitutional. The Fourth Circuit has said that. That’s what appears to have happened here.

[snip]

We need to know was this a narrowly tailored responsive set or did they just mark the entire iCloud responsive, thus rendering it a general warrant. We don’t know the answers to those questions.

Then, the FBI agent who realized he was reading privileged material described that he had been given the “full Cellebrite extraction” of Dan Richman’s phone to review, precisely that general warrant Donaleski feared. His supervisor said that the original agent had prepped the grand jury team with “a two-page document containing limited text message content only from May 11, 2017,” designed to avoid any taint. But Miles Starr appears to have presented eight pages of those texts to the grand jury; the Bates stamp for those texts include only a number, nothing to indicate they post-dated a privilege review by Richman.

After that, the Loaner AUSAs confessed that they had no fucking clue whether the material used to investigate Jim Comey had been scoped for responsiveness (though Comey’s team described that it looked like these were “raw returns for the search warrants at issue, unscoped for responsiveness and filtered for Mr. Richman’s privileges”).

The Order also required the government to provide, in writing, by the same deadline: “Confirmation of whether the Government has divided the materials searched pursuant to the four 2019 and 2020 warrants at issue into materials that are responsive and non-responsive to those warrants, and, if so, a detailed explanation of the methodology used to make that determination; A detailed explanation of whether, and for what period of time, the Government has preserved any materials identified as non-responsive to the four search warrants; A description identifying which materials have been identified as responsive, if any; and A description identifying which materials have previously been designated as privileged.” ECF No. 161 at 1-2.

Despite certifying on November 6 that it had complied with the Court’s Order, ECF No. 163, the government did not provide this information until the evening of November 9, 2025, in response to a defense inquiry. The government told the defense that it “does not know” whether there are responsive sets for the first, third, and fourth warrants, or whether it has produced those to the defense, and said that in that regard, “we are still pulling prior emails” and the “agent reviewed the filtered material through relativity but there appears to be a loss of data that we are currently trying to restore.”

Then, in one of their response briefs, the government effectively threw out half their evidence, including all the texts from Richman’s phone.

At the earlier hearing, Fitzpatrick warned the government not to use any violative material.

THE COURT: The Court authorized you to search and to seize, or to seize primarily, a very specific subset of information; that’s it. It’s the government’s burden to comply with that court order. You need to confidently explain to me how you have done that. You need to confidently explain how you have complied strictly with the Court’s order. If you can do that, then I suspect that that narrow window of time, you probably still can review, at least pending the outcome of the other motions.

He even ordered them not to review any materials seized from those search warrants until further order of the Court.

ORDERED that the Government, including any of its agents or employees, shall not review any of the materials seized pursuant to the four 2019 and 2020 search warrants at issue until further order of the Court;

In the middle of this, Comey argued that if Halligan presented unlawfully seized material to the grand jury, then Pam Bondi’s review of the grand jury materials — the first one, on October 31 — might also constitute a violation of Comey’s Fourth Amendment.

2 Concerns about taint arising from the improper use of potentially privileged and unconstitutionally-obtained materials are heightened because of the government’s continued use of the materials obtained pursuant to the warrants and grand jury transcripts. On October 31, 2025, the Attorney General purported to ratify the indictment based on her review of the grand jury proceedings. ECF No. 137-1 at 2-3. If that review entailed further improper use of privileged or unconstitutionally-obtained materials insofar as they were presented to the grand jury, it casts further doubt on the propriety of the government’s conduct of this case. The government produced the grand jury materials on November 5, 2025 to Judge Currie for in camera review, and thus could quickly produce the same materials to the defense. See ECF No. 158.

So to sum up so far: Jim Comey said, you violated my Attorney-Client privilege and my Fourth Amendment rights. And it’s likely that when Pam Bondi reviewed that transcript where unlawfully seized materials were presented, she did too.

And then Pam Bondi — after her Counselor assured Judge Currie that Halligan is closely supervised — reviewed the grand jury transcripts again.

The ones that likely rely on unlawfully seized materials.