Under Cover of the Nunes Memo, Russian Spooks Sneak Openly into Meetings with Trump’s Administration

On December 17, Vladimir Putin picked up the phone and called Donald Trump.

Ostensibly, the purpose of the call was to thank Trump for intelligence the US provided Russia that helped them thwart a terrorist attack. Here’s what the White House readout described.

President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia called President Donald J. Trump today to thank him for the advanced warning the United States intelligence agencies provided to Russia concerning a major terror plot in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Based on the information the United States provided, Russian authorities were able to capture the terrorists just prior to an attack that could have killed large numbers of people. No Russian lives were lost and the terrorist attackers were caught and are now incarcerated. President Trump appreciated the call and told President Putin that he and the entire United States intelligence community were pleased to have helped save so many lives. President Trump stressed the importance of intelligence cooperation to defeat terrorists wherever they may be. Both leaders agreed that this serves as an example of the positive things that can occur when our countries work together. President Putin extended his thanks and congratulations to Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director Mike Pompeo and the CIA. President Trump then called Director Pompeo to congratulate him, his very talented people, and the entire intelligence community on a job well done!

Putin, of course, has a history of trumping up terrorist attacks for political purposes (which is not to say he’s the only one).

In Trump’s Russia, top spooks come to you

That call that Putin initiated serves as important background to an event (or several — the details are still uncertain) that happened earlier this week, as everyone was distracted with Devin Nunes’ theatrics surrounding his memo attacking the Mueller investigation into whether Trump has engaged in a conspiracy with Russia. All three of Russia’s intelligence heads came to DC for a visit.

The visit of the sanctioned head of SVR, Sergey Naryshkin — Russia’s foreign intelligence service — was ostentatiously announced by Russia’s embassy.

SVR is the agency that tried to recruit Carter Page back in 2013, and which has also newly been given credit for the hack of the DNC in some Dutch reporting (and a recent David Sanger article). It’s clear that SVR wanted Americans to know that their sanctioned head had been through town.

As the week went on, WaPo reported that FSB’s Alexander Bortnikov and GRU’s Colonel General Igor Korobov had also been through town (GRU has previously gotten primary credit for the hack and Korobov was also sanctioned in the December 2016 response, and FSB was described as having an assisting role).

Pompeo met with Sergey Naryshkin, the head of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service or SVR, and Alexander Bortnikov, who runs the FSB, which is the main successor to the Soviet-era security service the KGB.

The head of Russia’s military intelligence, the GRU, also came to Washington, though it is not clear he met with Pompeo.

A senior U.S. intelligence official based in Moscow was also called back to Washington for the meeting with the CIA chief, said a person familiar with the events, who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive meeting.

Treasury defies Congress on Russian sanctions

These visits have been associated with Trump’s decision not to enforce congressionally mandated sanctions, claiming that the threat of sanctions is already working even as Mike Pompeo insists that Russia remains a threat. In lieu of providing a mandated list of Russians who could be sanctioned, Treasury basically released the Forbes list of richest Russians, meaning that the sanction list includes people who’re squarely opposed to Putin. In my opinion, reporting on the Forbes list underplays the contempt of the move. Then, today, Treasury released a memo saying Russia was too systematically important to sanction.

Schumer’s questions and Pompeo’s non-answers

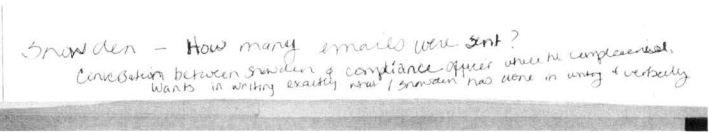

Indeed, Chuck Schumer emphasized sanctions in a letter he sent to Dan Coats, copied to Mike Pompeo, about the Naryshkin visit (the presence of the others was just becoming public).

As you are well aware, Mr. Naryshkin is a Specially Designated National under U.S. sanctions law, which imposes severe financial penalties and prohibits his entry into the U.S. without a waiver. Moreover, the visit of the SVR chief occurred only days before Congress was informed of the president’s decision not to implement sanctions authorized the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which was passed with near unanimous, bipartisan support. CAATSA was designed to impose a price on Russian President Vladimir Putin and his cronies for well-documented Russian aggression and interference in the 2016 election. However, the administration took little to no action, even as Russia continues its cyberattacks on the U.S.

Certainly, that seems a fair conclusion to draw — that by emphasizing Naryshkin’s presence, Russia was also boasting that it was immune from Congress’ attempts to sanction it.

But Mike Pompeo, who responded to Schumer, conveniently responded only to Schumer’s public comments, not the letter itself.

I am writing to you in response to your press conference Tuesday where you suggested there was something untoward in officials from Russian intelligence services meeting with their U.S. counterparts. Let me assure you there is not. [my emphasis]

This allowed Pompeo to dodge a range Schumer’s questions addressing Russia’s attacks on the US.

What specific policy issues and topics were discussed by Mr. Naryshkin and U.S. officials?

- Did the U.S. officials who met with Mr. Naryshkin raise Russia’s interference in the 2016 elections? If not, why was this not raised? If raised, what was his response?

- Did the U.S. officials who met with Mr. Naryshkin raise existing and congressionally-mandated U.S. sanctions against Russia discussed? If not, why was this not raised? If raised, what was his response?

- Did the U.S. officials who met with Mr. Naryshkin raise ongoing Russian cyber attacks on the U.S. and its allies, including reported efforts to discredit the Federal Bureau of Investigation and law enforcement investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections? If not, why was this not raised? If raised, what was his response?

- Did the U.S. officials who met with Mr. Naryshkin make clear that Putin’s interference in the 2018 and 2020 elections would be a hostile act against the United States? If not, why was this not raised? If raised, what was his response?

Instead of providing responses to questions about Russian tampering, Pompeo instead excused the whole meeting by pointing to counterterrorism, that same purpose, indeed — the same attack — that Putin raised in his December phone call.

We periodically meet with our Russian intelligence counterparts — to keep America safe. While Russia remains an adversary, we would put American lives at greater risk if we ignored opportunities to work with the Russian services in the fight against terrorism. We are proud of that counterterror work, including CIA’s role with its Russian counterparts in the recent disruption of a terrorist plot targeting St. Petersburg, Russia — a plot that could have killed Americans.

[snip]

Security cooperation between our intelligence services has occurred under multiple administrations. I am confident that you would support CIA continuing these engagements that are aimed at protecting the American people.

The contempt on sanctions makes it clear this goes beyond counterterrorism

All this together should allay any doubt you might have that this meeting goes beyond counterterrorism, if, indeed, it even has anything to do with counterterrorism.

Just as one possible other topic, in November, WSJ reported that DOJ was working towards charging Russians involved in the hack after the new year.

The Justice Department has identified more than six members of the Russian government involved in hacking the Democratic National Committee’s computers and swiping sensitive information that became public during the 2016 presidential election, according to people familiar with the investigation.

Prosecutors and agents have assembled evidence to charge the Russian officials and could bring a case next year, these people said. Discussions about the case are in the early stages, they said.

If filed, the case would provide the clearest picture yet of the actors behind the DNC intrusion. U.S. intelligence agencies have attributed the attack to Russian intelligence services, but haven’t provided detailed information about how they concluded those services were responsible, or any details about the individuals allegedly involved.

Today, Russia issued a new warning that America is “hunting” Russians all over the world, citing (among others) hacker Roman Seleznev.

“American special services are continuing their de facto hunt for Russians all over the world,” reads the statement published on the ministry’s website on Friday. The Russian diplomats also gave several examples of such arbitrary detentions of Russian citizens that took place in Spain, Latvia, Canada and Greece.

“Sometimes these were actual abductions of our compatriots. This is what happened with Konstantin Yaroshenko, who was kidnapped in Liberia in 2010 and secretly taken to the United States in violation of Liberian and international laws. This also happened in 2014 with Roman Seleznyov, who was literally abducted in the Maldives and forcefully taken to American territory,” the statement reads.

The ministry also warned that after being handed over to the US justice system, Russian citizens often encounter extremely biased attitudes.

“Through various means, including direct threats, they attempt to coerce Russians into pleading guilty, despite the fact that the charges of them are far-fetched. Those who refuse get sentenced to extraordinarily long prison terms.”

And, as I noted earlier, Trey Gowdy — one of the few members of Congress who has seen where Mueller is going with this investigation — cited the import of the counterintelligence case against Russia in a Sunday appearance.

CHRIS WALLACE: Congressman, we’ll get to your concerns about the FBI and the Department of Justice in a moment. But — but let me begin first with this. Do you still trust, after all you’ve heard, do you still trust Special Counsel Robert Mueller to conduct a fair and unbiased investigation?

REP. TREY GOWDY, R-SC, OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN: One hundred percent, particularly if he’s given the time, the resources and the independence to do his job. Chris, he didn’t apply for the job. He’s where he is because we have an attorney general who had to recuse himself. So Mueller didn’t raise his hand and say, hey, pick me. We, as a country, asked him to do this.

And, by the way, he’s got two — there are two components to his jurisdiction. There is a criminal component. But there’s also a counterintelligence component that no one ever talks about because it’s not sexy and interesting. But he’s also going to tell us definitively what Russia tried to do in 2016. So the last time you and I were together, I told my Republican colleagues, leave him the hell alone, and that’s still my advice.

Schumer and other Democrats demanding answers about this visit might think about any ways the Russians might be working to undermine Mueller’s investigation or transparency that might come of it.

Three weeks of oversight free covert action

The timing of this visit is particularly concerning for another reason. In the three week continuing resolution to fund the government passed on January 22, the House Appropriations Chair Rodney Frelinghuysen added language that would allow the Administration to shift money funding intelligence activities around without telling Congress. It allows funds to,

“be obligated and expended notwithstanding section 504(a)(1) of the National Security Act of 1947.”

Section 504(a)(1) is the piece of the law that requires intelligence agencies to spend money on the program the money was appropriated for. “Appropriated funds available to an intelligence agency may be obligated or expended for an intelligence or intelligence-related activity only if those funds were specifically authorized by the Congress for use for such activities; or …”

The “or” refers to the intelligence community’s obligation to inform Congress of any deviation. But without any obligation to spend funds as specifically authorized, there is no obligation to inform Congress if that’s not happening.

Since the only real way to prohibit the Executive is to prohibit them to spend money on certain things, the change allows the Trump Administration to do things they’ve been specifically prohibited from doing for the three week period of the continuing resolution.

Senators Burr and Warner tried to change the language before passage on January 22, to no avail.

This year’s Defense Authorization included a whole slew of limits on Executive Branch activity, including mandating a report if the Executive cooperates with Russia on Syria and prohibiting any military cooperation until such time as Russia leaves Ukraine. It’s possible the Trump Administration would claim those appropriations-tied requirements could be ignored during the time of the continuing resolution.

Which just happened to cover the period of the Russian visit.

Our friends are getting nervous

Meanwhile, both before and after the visit, our allies have found ways to raise concerns about sharing intelligence with the US in light of Trump’s coziness with Russia. A key subtext of the stories revealing that Netherlands’ AIVD saw Russian hackers targeting the Democrats via a hacked security camera was that Rick Ledgett’s disclosure of that operation last year had raised concerns about sharing with the US.

President elect Donald Trump categorically refuses to explicitly acknowledge the Russian interference. It would tarnish the gleam of his electoral victory. He has also frequently praised Russia, and president Putin in particular. This is one of the reasons the American intelligence services eagerly leak information: to prove that the Russians did in fact interfere with the elections. And that is why intelligence services have told American media about the amazing access of a ‘western ally’.

This has led to anger in Zoetermeer and The Hague. Some Dutchmen even feel betrayed. It’s absolutely not done to reveal the methods of a friendly intelligence service, especially if you’re benefiting from their intelligence. But no matter how vehemently the heads of the AIVD and MIVD express their displeasure, they don’t feel understood by the Americans. It’s made the AIVD and MIVD a lot more cautious when it comes to sharing intelligence. They’ve become increasingly suspicious since Trump was elected president.

Then, the author of a book on Israeli’s assassinations has suggested that the intelligence Trump shared with the Russians goes beyond what got publicly reported, goes to the heart of Israeli intelligence operations.

DAVIES: So if I understand it, you know of specific information that the U.S. shared with the Russians that has not been revealed publicly and that you are not revealing publicly?

BERGMAN: The nature of the information that President Trump revealed to Foreign Minister Lavrov is of the most secretive nature.

Finally, a piece on the Nunes memo out today suggests the British will be less likely to share intelligence with Trump’s administration after the release of the memo (though this is admittedly based on US congressional claims, not British sources).

Britain’s spy agencies risk having their intelligence methods revealed if Donald Trump releases a controversial memo about the FBI, congressional figures have warned.

The UK will be less likely to share confidential information if the secret memo about the Russian investigation is made public, according to those opposing its release.

Clearly, this meeting goes beyond counterterrorism cooperation. And given the way that both Treasury and CIA have acted contemptuously in the aftermath of the visit, Schumer and others should be far more aggressive in seeking answers about what this visit really entailed.

Update: I’ve added the section on Section 504.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)