Applying Existentialist Ethics

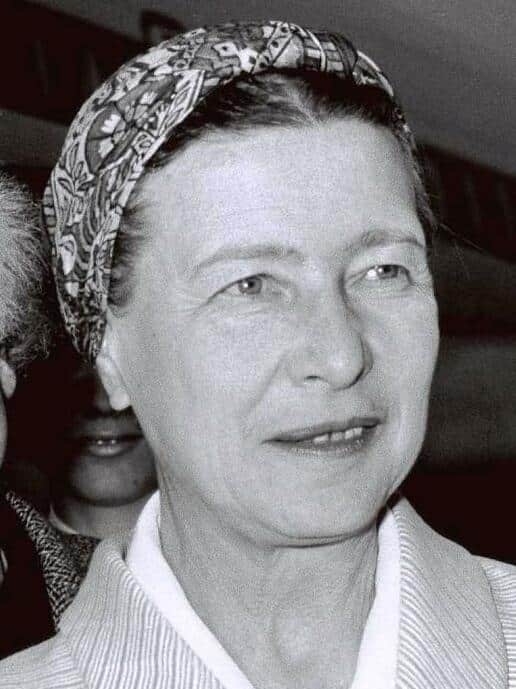

The third and last chapter of The Ethics Of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir applies the ideas in the first two chapters to the question how one should respond to oppression and tyranny. She focuses on the responses to the Nazis and to the oppression of the proletariat by the capitalists.

The Aesthetic Attitude

Many Frenchmen also sought relief in this thought in 1940 and the years which followed. “Let’s try to take the point of view of history,” they said upon learning that the Germans had entered Paris. And during the whole occupation certain intellectuals sought to keep “aloof from the fray” and to consider impartially contingent facts which did not concern them. Pp. 75-6.

De Beauvoir calls this the aesthetic attitude, and says it is merely flight from reality. In the real world, we are all in this together. What happens to others is our concern. Our freedom exists only in the presence and freedom of others. The aesthetic attitude is an effort to hide from the reality of our own freedom. These people aren’t free: they are locked in a tiny bubble of like-minded cowards (my word, not de Beauvoir’s), people afraid of the existential truth of human existence in the moment of crisis.

She says that the responsibility of the intellectual, the artist, and the critic is to create awareness of existential freedom as a common goal for all humanity, and to encourage everyone to accept the demands of that freedom in the face of tyranny.

How can we do that today? It seems to me that the people carrying whistles and filming the thugs attacking my neighbors in Chicago demonstrate their freedom and challenge to the rest of us to exercise our freedom as best we can. [As a former lawyer I remind everyone that if the goons arrest you while you’re demonstrating your freedom, STFU.]

Freedom And Liberation

The next two sections take up the ethics of dealing with oppression and tyranny. She says we must resist both, with violence if necessary. De Beauvoir follows Kant’s assertion that we are not to treat other people as means to our ends, or as objects, as we would a lump of coal, but as ends in themselves, autonomous creatures acting from their own freedom.

De Beauvoir conflates the ideas of tyranny and oppression, but there’s a useful distinction. The capitalist system is oppressive, in the Marxian sense. The capitalists extract most of the wealth created by systems of production. They claim that this is the natural order of things, and that nothing can be done to correct it. I tell that story in this post.

The oligarchs tell their story everywhere, and vilify every competing story as socialist or communist while never taking it on seriously. This is a standard tactic of the dominant class, as we saw reading Culture and Power: The Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu, as here.

Outside the workplace, the proles are free to pursue their own projects. De Beauvoir is contemptuous of many of those projects, seeing them as tools of further oppression:

… the trick of “enlightened” capitalism is to make [the worker] forget about his concern with genuine justification, offering him, when he leaves the factory where a mechanical job absorbs his transcendence, diversions in which this transcendence ends by petering out: there you have the politics of the American employing class which catches the worker in the trap of sports, “gadgets,” autos, and frigidaires. Pp. 87-88.

Tyranny is better seen as the domination of a social order by one person who treats all others as ends, fit only to fulfill the desires of the tyrant. Tyrants can limit the freedom of every individual in all aspects of their lives at all times, whether or not they choose to do so.

The difference between these two is reflected in the means used to resist. Oppression operates largely by mystification. People are acculturated to the capitalist system from birth, and have no means to construct an alternate view or attract a significant number of people even to question it. Thus this post. But this kind of change only occurs when enough people are ready to move into a different form of economic organization, Violence won’t make anyone change their minds about capitalism.

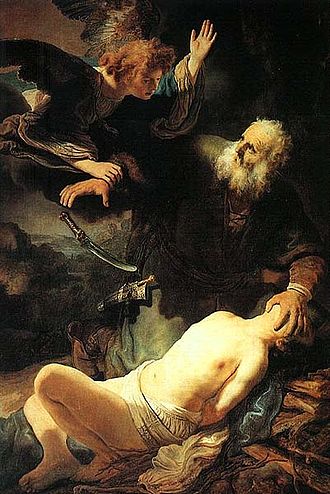

Tyranny either dies when the tyrant’s line dies out, as with Soviet Russia, or it is resisted with violence, as with Hitler and Mussolini. Treating the tyrants and their minions as objects is necessary if we are to remove their ability to restrict the freedom of ourselves and others. And it is fully justified.

The desirable thing would be to re-educate [them]; it would be necessary to expose the mystification and to put the men who are its victims in the presence of their freedom. But the urgency of the struggle forbids this slow labor. We are obliged to destroy not only the oppressor but also those who serve him, whether they do so out of ignorance or out of constraint. P. 98.

The Future

De Beauvoir says that the struggle for freedom is never-ending. In part this is the necessary result of her notion of freedom as generating new ways to be human, opening new futures for all. But also it results from the fact that we are merely human, and thus operate under many different forces. Many people will not accept their freedom, some will not accept new freedoms, others will accept it partially, as with the Adventurer, and still others will use it for their own private ends. Some will use it to oppress or tyrannize others. Some will not be willing to see themselves as oppressors in the Capitalist System or otherwise. The future is open, but only if we make it so.

Conclusion

One problem with reading texts like this one is the nagging feeling of elitism they generate. Throughout this book, de Beauvoir is judgmental. The descriptions of her categories is a good example, as is her snide comment on Frigidaires above. In the end, she seems to say that most people will never achieve her notion of freedom, but that it is the goal of people like her to show everyone their freedom and let them choose. Should we characterize that as elitism? If so, is that bad, or just annoying to people unwilling to cope with her level of abstraction?

In the end, I don’t see answers to the question I raised at the outset: what should we do to defeat rising fascism. We see signposts for a bad future in Arendt and Polyani but we don’t see off-ramps. We get ideas about how people think in other readings. We see responses and justifications for those responses in de Beauvoir. It’s disappointing that the best minds of that era have no answers for their future readers. But there we are. People who want their freedom will find a way. Maybe it starts with whistles.