Trumpist Moral Choice

My last post and Rayne’s excellent post A Lapsed Catholic’s Sunday Bible Study raise a question: how does a person claim to be both a Christian and a Trumpist? These two things seem utterly incompatible. In this post I look at this question using a formulation from Lecture 3 of Christine Korsgaard’s book The Sources Of Normativity, augmented by Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Ethics Of Ambiguity.

Identities

Normativity is a neutral word for moral principles. The point of Korsgaard’s book is to show how ethics can be formulated and justified without recourse to external sources, like sacred books.

Korsgaard begins with a description of the individual. She says we adult humans are reflective creatures. We are able to examine our behavior and evaluate it against standards we choose. This is the same ability we use to decide on plans of action. She says that when we are deciding how to act we require reasons. For example, when we experience hunger mid-afternoon, we have to decide whether to grab a snack or not. We give ourselves reasons for each and decide.

Korsgaard says we have different identities. We are spouses, parents, members of a tribe, residents of a city, workers, followers of religions, citizens of a nation. We are also human beings, members of an entire species. Each identity carries with it a set of behaviors, norms, and obligations.

For example, I was a lawyer. I operated under norms set by the ethical requirements of Tennessee. I practiced in the Bankruptcy Courts of Nashville and was bound by an unwritten set of norms established and enforced by my colleagues and the courts. Those norms were reasons to act in particular ways, even when other actions would be easier or more rewarding.

I think these two ideas, reflection and identity, fit nicely with other books I’ve discussed here. We looked at Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus in the discussion of Culture and Power: The Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. Habitus is much like identities. The notion of reflection is very close to Michael Tomasello’s description of decision-making in The Evolution of Agency.

Korsgaard says that the demands of our identities can clash, and that is what gives rise to moral dilemmas. Here’s an overly simplified example. The father of the guy who murdered Charlie Kirk is apparently a Mormon, a father, and a citizen of Utah, and of course a human being. When confronted with the act of his son, he has to make a moral choice. His identities give rise to reasons for actions, and his internal arbiter has to choose. He chose to act on the norms of a good citizen and a good Mormon, and encourage his own son to turn himself in, despite the fact that Utah is a death penalty state.

It seems that in effect he has to stand away from his identities and examine their claims. It is as if there is another identity, not a social role, but something that is personal to him. Korsgaard refers to this as his internal arbiter. This is the source of his own normativity and in fact, the source of his identity. As Korsgaard puts it:

… [W]e require reasons for action, a conception of the right and the good. To act from such a conception is in turn to have a practical conception of your identity, a conception under which you value yourself and find your life to be worth living and your actions to be worth undertaking. That conception is normative for you and in certain cases it can obligate you, for if you do not allow yourself to be governed by any conception of your identity then you will have no reason to act and to live. P. 122.

The Christian Trumpist

It appears that there is a conflict between the moral teachings of Christianity and the actions of the Trump administration’s program of attacking immigrants and anyone who gets near them. The conflicts with The Parable of the Good Samaritan and the verses cited by Rayne are obvious.

I can think of three ways Trumpist Christians might explain their support for these atrocities. First, they may refuse to see the conflict. For example, if the Trumpist is a serious person in de Beauvoir’s sense, they may have internalized each of their identities so deeply that they only need to identify the situation in order to respond. If the person sees the question purely as a political question, only the Trumpist identity is in action and there is no conflict.

So, if the libtard asks Trumpist Uncle his opinion about the vile treatment of ICE detainees, Trumpist Uncle sees it as political and never ever sees it as a question about Christian values. In such a case Trumpist Uncle can regard himself under both identities without any recourse to an internal moral arbiter.

But worse, I’ve often wondered if Trumpists have an internal arbiter of any kind. Korsgaard and de Beauvoir both say that humans are reflective creatures, able to step back from their behavior and judge it. I don’t see that happening in the Trumpists I see in the media.

Here’s another possibility: a) the Christian and Trumpist identities must both submit to the internal arbiter of the individual to determine the one which will dictate action; or b) the identity as a Christian is the fundamental to the internal arbiter, the one by which all others are judged.

In either of these cases, if the Trumpist identity controls, it’s fair to ask the person in what sense are they actually Christians. If it means I’m a Christian except when Trump makes a demand, are you truly a Christian?

There’s at least one more possibility. Maybe the Christian leaders that the person follows has explained everything in advance. For example, apparently many preachers assert that Trump is the imperfect tool used by the Almighty for good ends, followed by the claim that in this Trump is like King David. 1 Samuel 17 – 1 Kings 2:10.

I wonder how many Christians have read this story themselves. I have, and I reread it for this post. There is no way in which Trump is like King David. First, Trump is a draft-dodging coward who gets other people to do his dirty work (except around Epstein?). David was a powerful warrior, who spent much of his life fighting in actual wars to protect and expand the lands of the Chosen People.

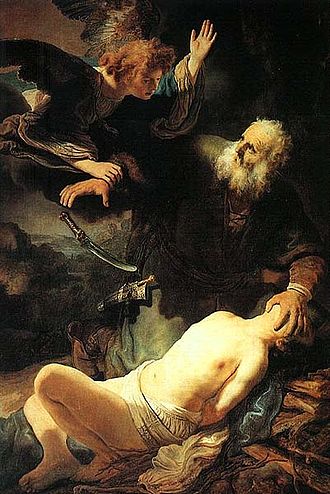

Second, David did in fact sin, again and again. But in each case he repented, and in each case he was punished by the Almighty even after he repented. His biggest crime was the abuse of Bathsheba (the front page art is Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at the Bath, at the Louvre).

2 One evening David got up from his bed and walked around on the roof of the palace. From the roof he saw a woman bathing. The woman was very beautiful, 3 and David sent someone to find out about her. The man said, “She is Bathsheba, the daughter of Eliam and the wife of Uriah the Hittite.” 4 Then David sent messengers to get her. She came to him, and he slept with her. (Now she was purifying herself from her monthly uncleanness.) Then she went back home. 5 The woman conceived and sent word to David, saying, “I am pregnant.”

David first tried to get Uriah to sleep with her to cover his adultery, and when that didn’t work he had his top general put Uriah in the heat of the battle where he was killed.

The Almighty sent the prophet Nathan to tell David he would be punished for this heinous evil. David repents, as he does whenever he realizes he has sinned against the Almighty. But he is punished nevertheless by the treason and death of his beloved son Absalom, and by a life of war.

Trump has never repented any of his terrible sins, and has only rarely been held accountable for anything.

Actual Christians have at least some familiarity with the Bible, especially the important stories. How could anyone see anything of Trump in King David? How is this story a plausible justification for voting for Trump? If a Trumpist Christian bothered to read the story of David would they grasp this? Or is this a bit of evidence that they do not judge moral issues for themselves?