Spill! The EDVA Case against Jim Comey Could Well Harm the Even More Corrupt SDFL Case

It looks increasingly likely that because someone snuck a peek into Jim Comey’s privileged communications — or, because Tyler Lemons cares enough about his bar license that he disclosed that someone snuck a peek into Comey’s privileged communications — Comey may get a ruling that the government violated his Fourth Amendment rights, throwing out some of the material used in the government’s filing laying out the theory of their case.

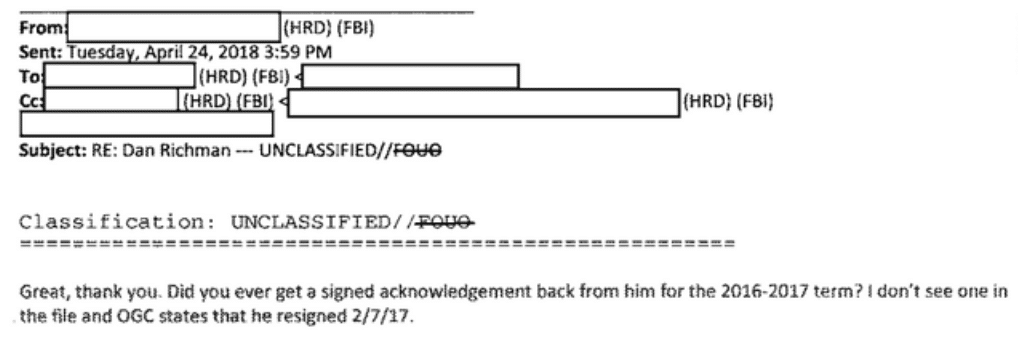

The exhibits to that filing which were seized from Dan Richman include a bunch of communications sent from two different Columbia University emails, as well as texts sent on Richman’s phone.

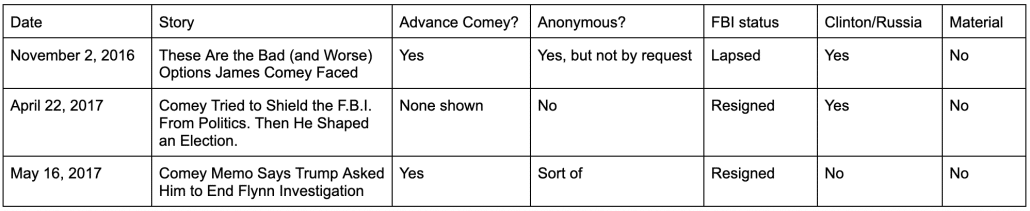

- January 2, 2015: Letter stating that Richman would not comment on matters he “work[s] on for the Bureau” [1st Columbia email]

- October 29, 2016: Text saying, “The country can’t seem to handle your finding stuff” [2nd Columbia email]

- October 30, 2016: Richman offering to write an op-ed for NYT [2nd Columbia email]

- November 1-2, 2016: Comey suggests perhaps Richman can make Mike Schmidt smarter [2nd Columbia email]

- November 2, 2016: Richman noting story about Hillary [2nd Columbia email]

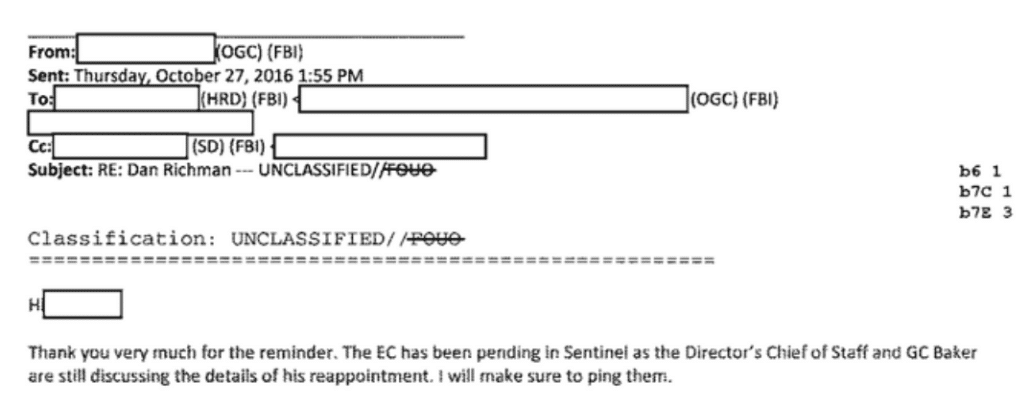

- February 11, 2017: Richman recruiting Chuck Rosenberg for article [1st Columbia email]

- April 23, 2017: Email to Richman thanking him [Columbia email]

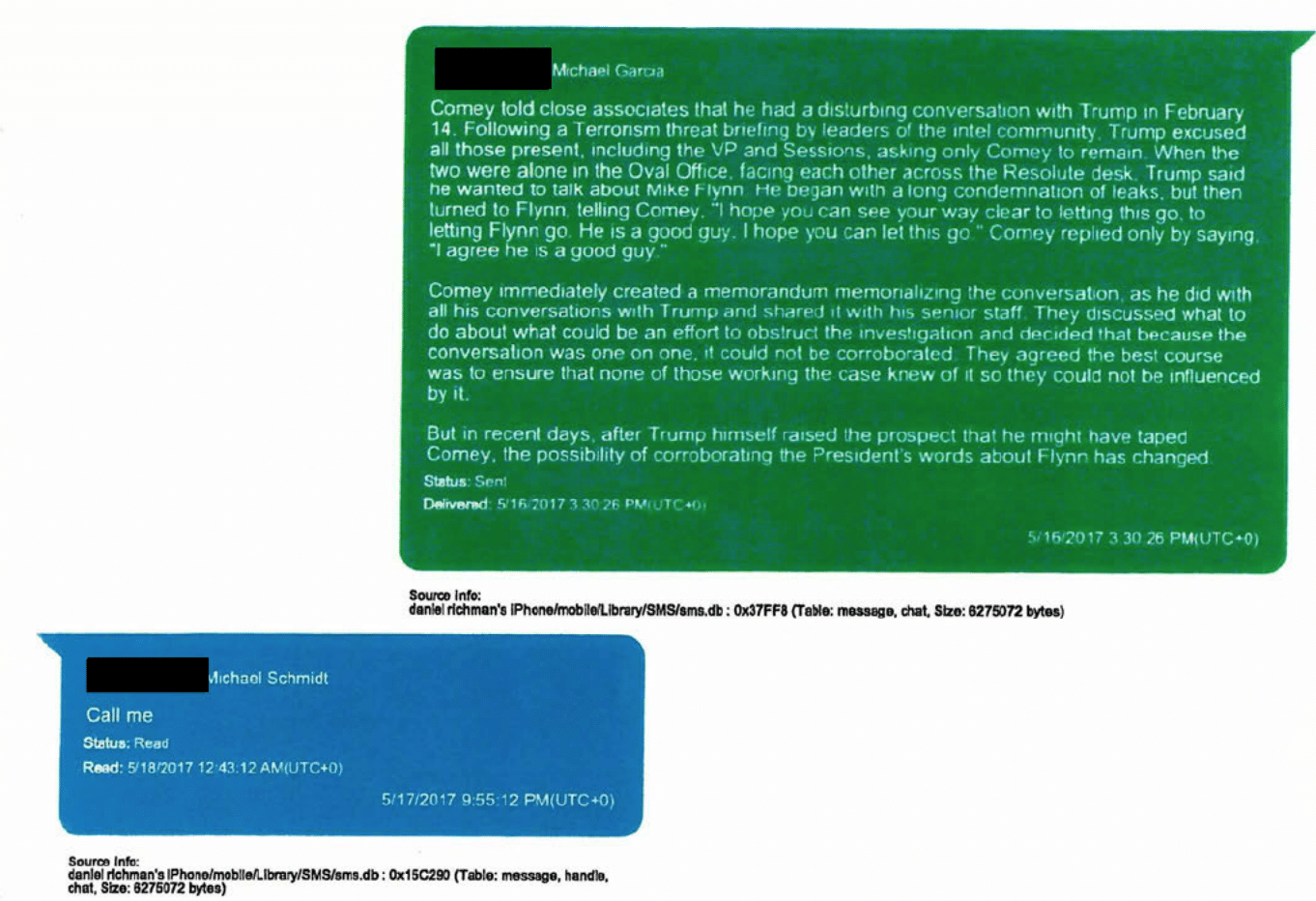

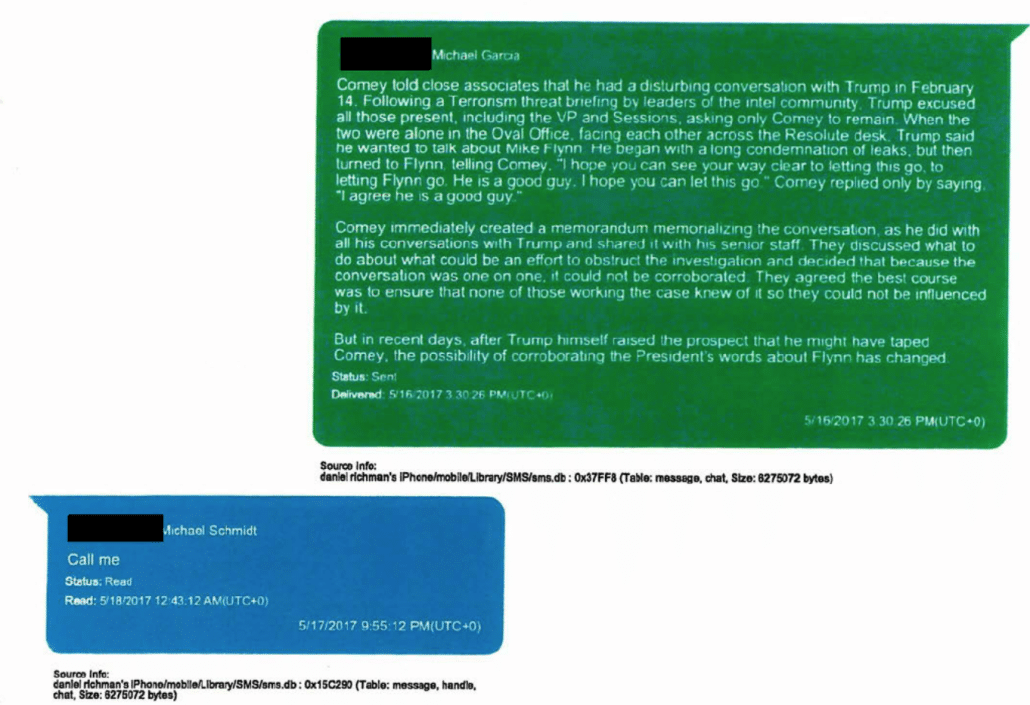

- May 2017: Texts between Schmidt and Richman [Dan Richman’s phone]

As Rebekah Donaleski described the warrants in Wednesday’s hearing, the Columbia emails likely came from a warrant served on the university in October 2019, whereas the texts should have only been available via the fourth warrant on Richman’s phone, but as I’ll show, may have instead come from unlawful searches from the hard drive seized with the first warrant in August 2019.

- August 29, 2019: FBI seizes Richman’s hard drive. The government does a privilege review of that, not Richman.

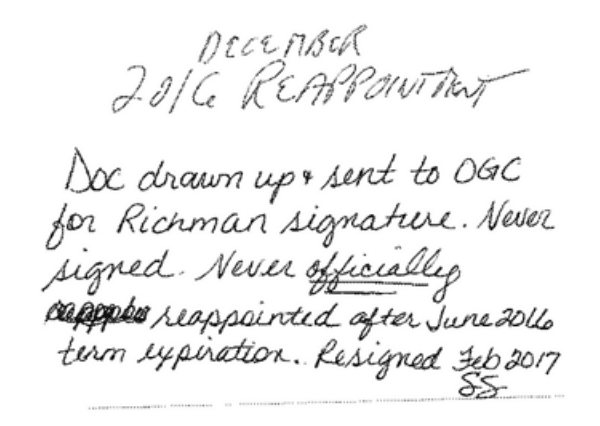

- October 2019: FBI obtains emails from Columbia. Richman withheld privileged or sensitive (from students), but conducted no responsiveness review.

- January 2020: FBI obtains Richman’s iCloud. His attorney did a privilege review. The warrant specifically said it could not seize privileged material.

- June 4, 2020: FBI gets warrants to access iPhone and iCloud back-ups on the original hard drive.

The arguably legal emails don’t prove DOJ’s case

Aside from the fact that the FBI accessed them without a warrant tailored to the current investigation, the two bolded emails were clearly responsive to the investigation into whether Richman leaked the SVR materials in advance of the April 22, 2017 story about them. But as I noted here, they don’t help the government prove that Comey lied to Ted Cruz about authorizing Richman, while he was at FBI, to be an anonymous source for a story about the Hillary investigation because:

- There’s no evidence of Comey’s involvement in the story in advance

- The emails unquestionably post-date Richman’s departure from FBI (Anna Bower expanded on the work I did to show that Richman was arguably never formally “at FBI” in this period)

- Richman was a named source in the story

The January 2, 2015 email might be legal, but who cares? It doesn’t help the government’s case at all (and most likely was used to mislead grand jurors about the time frame of Richman’s relationship with the FBI).

The emails that come closest to proving the government’s case may be out of scope

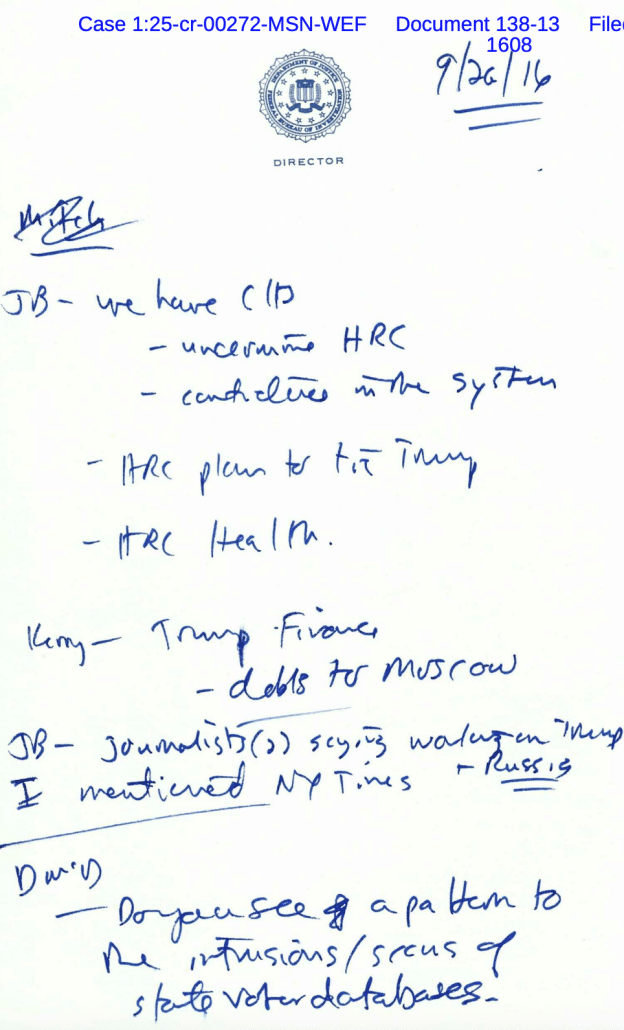

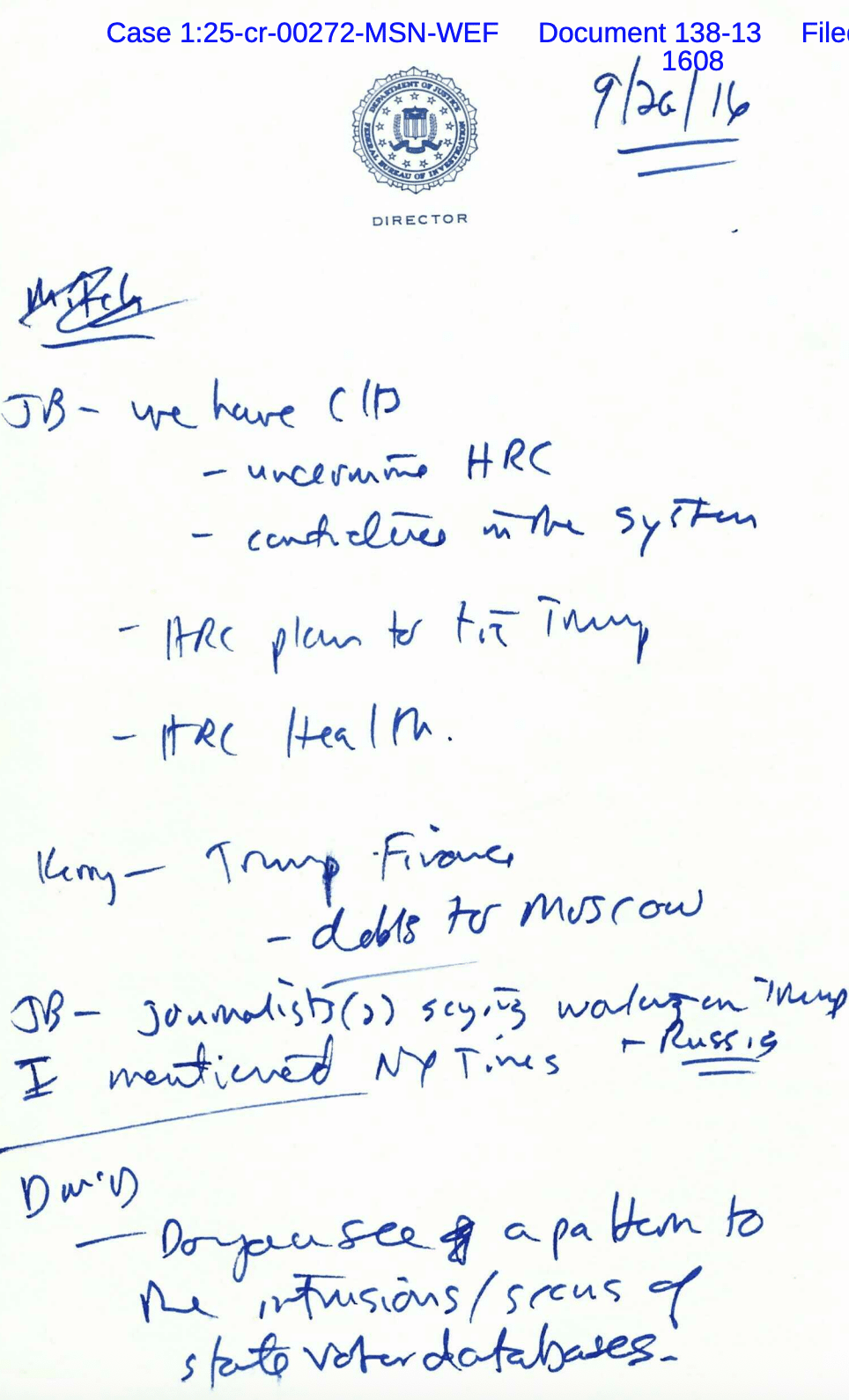

It’s less clear whether the emails from fall 2016 — the ones that best match the theory of the case — should have been accessible to investigators for the investigation into whether Comey lied to Ted Cruz. That’s because — at least per a November 22, 2019 interview — Richman didn’t learn about the SVR emails until January 2017.

According to Richman, he and Comey had a private conversation in Comey’s office in January 2017. The conversation pertained to Comey’s decision to make a public statement on the Midyear Exam investigation. Comey told Richman the tarmac meeting between Lynch and Clinton was not the only reason which played into Comey’s statement on the Midyear Exam investigation. According to Richman, Comey told Richman of Lynch’s characterization of the investigation as a “matter” and not that of an investigation. Richman recalled Comey told him there was some weird classified material related to Lynch which came to the FBI’s attention. Comey did not fully explain the details of the information. Comey told Richman about the Classified Information, including the source of the information. Richman understood the information could be used to suggest Lynch might not be impartial with regards of the conclusion of the Midyear Exam investigation. Richman understood the information about Lynch was highly classified and it should be protected. Richman was an SGE at the time of the meeting.

Nothing in the hearing on Wednesday describes the date scope of the warrants. But immediately after she described this warrant, Doneleski raised doubts about whether the Columbia emails had been reviewed for responsiveness, with non-responsive emails sealed.

As Your Honor is aware, each of these warrants require the government to conduct a responsiveness review and then seal and not review the nonresponsive set. I don’t know if that happened here, and Mr. Lemons didn’t describe whether the government created a responsive set.

[snip]

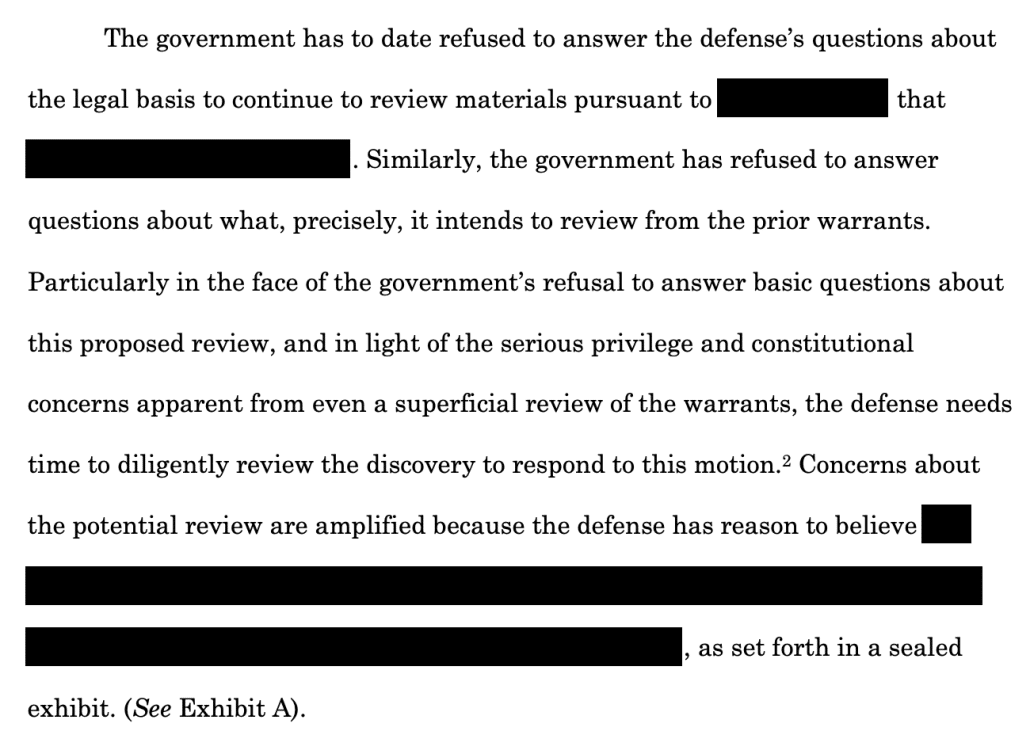

MS. DONALESKI: Judge, the government provided us with affidavits describing what happened; and from the affidavits, it sounds like the agents accessed the filtered returns, meaning both the nonresponsive and responsive set, because Mr. Richman’s counsel and Columbia did not conduct a responsiveness review. If that is indeed what they accessed, for the reasons we set forward in our papers, that clearly violates the Fourth Amendment because the government cannot then go back into a nonresponsive set that has not been identified responsive and continue searching pursuant to stale warrants for separate offenses.

If these emails were out of scope according to the 2019 warrants, then they should be sealed, inaccessible to anyone.

The privileged material was prohibited under the previous warrants

Tyler Lemons tried to excuse an agent for having read privileged communications by explaining that in those communications, Dan Richman used the name Michael Garcia.

MR. LEMONS: I don’t know the status — I don’t know if the team knew the status of their relationship. The other complicating factor, Your Honor — and we have two affidavits here that we’ve provided to the defense, and we have copies for the Court as well if you’d like to review it — one of the issues was the conversation that was being reviewed, the telephone name associated with one of the participants was Michael Garcia. And so it wasn’t as if the agent went in reviewing a conversation between James — the defendant and Daniel Richman; it was a conversation between the defendant and Michael Garcia. And so at a certain point, the agent began to understand the topics and the kind of factual — the history of the case; came to the conclusion that Michael Garcia looks like it’s actually Daniel Richman under a pseudonym or whatever it is. And at that point, it kind of brought into focus what, potentially, the conversations that the agent was looking at could be pertaining to.

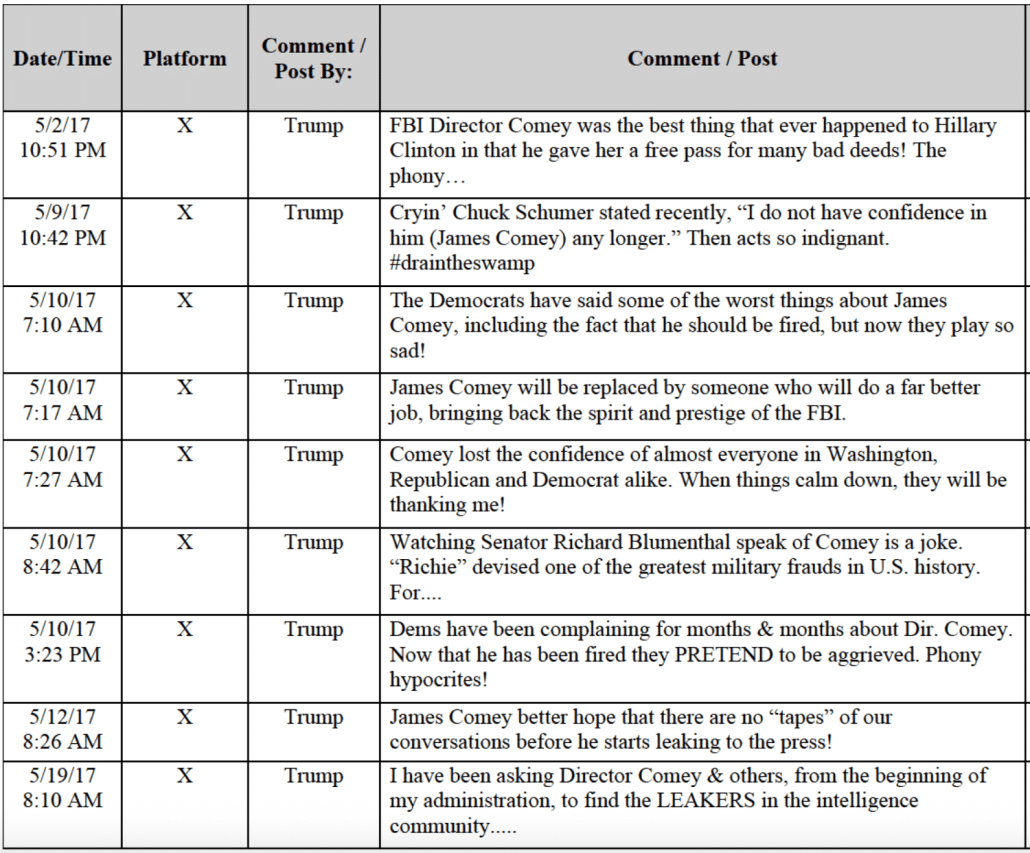

That’s the name Richman used in texts exchanged with Mike Schmidt about the memo Comey had documenting Trump asking to let the Mike Flynn case go and because of timing — Richman only formally represented Comey after he was fired on May 9 — it’s likely the privileged stuff is the counterpart to this discussion.

It’s unclear whether these texts would have been in scope for the Arctic Haze investigation. In addition to the leak crime, 18 USC 793, the government also investigated using government materials, 18 USC 641, converting government records for personal use. In an interrupted comment, Lemons claimed it was responsive, which it might have been to that second crime. Donaleski wondered how the government filed them if they paused all review.

The government filed, on Monday, text message chats that came from the Arctic Haze warrants.

The question is how privileged texts between Richman and Comey were available in the first place. Lemons blamed the review Richman did.

MR. LEMONS: It would appear that he was — I don’t know for sure, Your Honor, but my assumption and based on him raising his hand on this, is that he was reviewing material that had not been filtered by Daniel Richman or his attorneys.

But given Donaleski’s mention of that original warrant, the one for which Richman did not do a filter, I wonder if DOJ got unfiltered content by accessing the unfiltered backup (which is effectively how prosecutors got the most damning texts used against Hunter Biden at his trial).

However investigators got to the privileged texts, it doesn’t fix the problem because they still accessed stuff from Comey before he had had an ability to make privilege determinations. And Donaleski argued anything privilege was not permitted to be seized, so anything reviewed now would be unlawful.

the warrants themselves specify that the government could only seize non-privileged materials

[snip]

MS. DONALESKI: And so to the extent the government now wants to look at materials that Mr. Richman’s counsel identified as privileged, those were never within the scope of the warrants, so they were never properly seized by the government, so no one can look at those materials. They weren’t seized five years ago. The government’s filter team didn’t challenge those designations, so no one can look at them. There’s no case law that says the government can go back five years later under stale warrants for separate offenses to look at things that were not seized five years ago.

Here’s where things get interesting, though.

The Comey memos are unresponsive to this investigation

Comey’s team has until the 19th to submit a Fourth Amendment challenge to this material. I imagine their argument may include the privilege problem and the responsiveness problem.

But then there’s the issue of proving that these texts are relevant to this investigation.

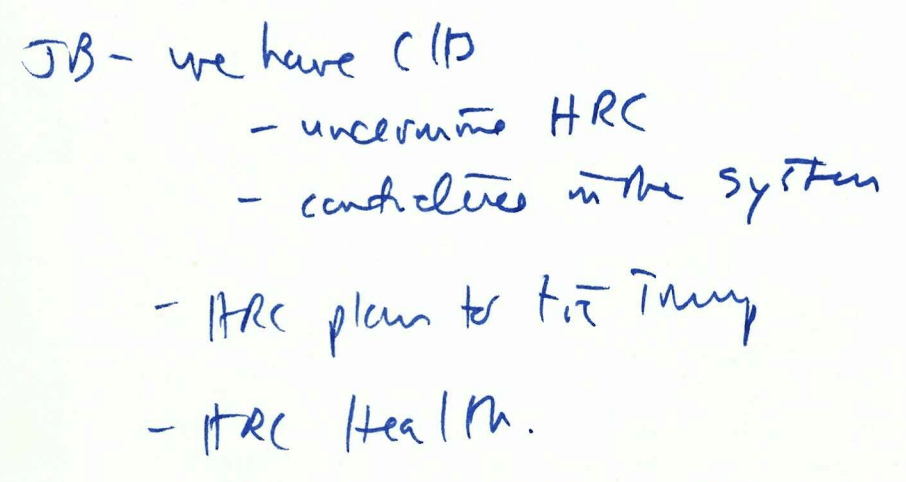

The Comey memos are undoubtedly responsive to the conspiracy conspiracy Trump is attempting to put together in Florida. This entire privilege effort seems to be an effort to clean up the material for the other investigation, not this one (which may be why James Hayes is on all the most important filings in this fight). The Florida case seems focused on claiming that by releasing the memo with the intent of precipitating a Special Counsel investigation, Comey unfairly harmed Trump.

But to argue these texts are responsive to this investigation, prosecutors would have to claim that they’re still relevant even after Comey admitted he had shared the memo via Richman, way back in 2017. Republicans have known that detail for years. His public admission of that fact is central to their claim that Trump had legitimate cause to worry about Comey leaking.

But to make that claim, they have to rely on the same false claim prosecutors (one of the filings that metadata attributes to James Hayes) made last month: that the act of sharing a memo that Comey understood to be unclassified was a criminal leak. (Starting in 2020, the government began to have problems charging 18 USC 641 in this context and precedent may rule it out any longer.)

That is, if prosecutors have to get a warrant for this material, it’s not clear they could get one for the EDVA case. If they tried for the Florida case, it could well blow up that case.

This whole effort started when, in the wake of the taint, prosecutors decided to use this case to quickly force though access to the privileged texts they saw. But thus far, the effort may make it harder to access material for both this case and that one.