The Republican Hundred Year War On Democracy

Our democracy is under attack, in a war planned and carried out by generations of filthy rich tight-wingers working primarily through the Republican Party. The war has come into the open under Trump, funded by the latest group of hideously rich dirtbags, the tech bros, and justified by a cadre of anti-intellectual grifters and yakkers like Curtis Yarvin.

We need to see the battlefield. Only then can we decide on how to act. As Marcy pointed out here, our role is explicitly political, as befits people who believe in democracy to our core.

The Battlefield

Introduction

The filthy rich have always held more power in this country than their numbers would support in a functioning democracy. Their control was somewhat restricted during the Progressive Era at the beginning of the 20th C., but SCOTUS did it’s best to beat back progressive laws. The political power of the filthy rich was sharply decreased during the Great Depression. Franklin Delano Roosevelt said this out loud in a 1936 speech in Madison Square Garden:

We had to struggle with the old enemies of peace—business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering.

They had begun to consider the Government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob.

Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.

The filthy rich hated FDR, and have spent nearly 100 years trying to destroy his legacy and our way of life. Generations of oligarchs arise over time in different sectors of the economy, and the wealth they control has increased steadily since then. But regardless of background, a significant number have a attacked every institution we have relied on as part of our heritage.

At the same time they have ruthlessly pursued their own interests without regard to the national interest.We know some names, like H.L. Hunt and other Texas Oilmen, and the Koch Brothers, and groups like the John Birch Society. We generally know about other threats, like the Christian Dominionists and White Nationalists.

The Republicans took over congress in 1946. One of their first acts was to pass the Taft-Hartley Act which was intended to undercut the power of organized labor. They continued a long tradition of\ anti-communism and anti-socialism. The Democrats responded by kicking out the Communists, many of whom were active in unions, and with the Civil Rights movement. The Democratic Party tradition of punching left has deep roots.

Trump and his henchmen are the culmination of this campaign. They are openly engaged in a war on every institution that wields power in our society and in or through our government. The success of a decades-long assault reveals the effect of that long-term guerrilla war by the Republicans.

Congress

Republican congressionals are weaklings. This has been a fixture of that party since the mid-90s. Newt Gingrich preached lock-step Republican voting, and Denny Hastert created the Hastert Rule, under which no legislation gets to the floor unless it can pass with only Republican votes.

Mitch McConnell made it his job to make sure that Obama couldn’t pass any legislation. He whipped Republican Senators so viciously they did his bidding. In his first term Trump violently assaulted Republicans who defied his orders. The party internalized fear so completely that it attacked its own members who voted to impeach Trump.

Now Trump simply ignores laws he doesn’t like, including spending laws, and arrests Democratic lawmakers on groundless charges.

The Administrative State

Under FDR, Congress began to empower agencies to carry out specific tasks necessary for a modern government. This gave rise to the administrative state. Republicans hate it. Ever since its inception, they and corporate Democrats have worked to hamstring agencies.

Conservative legal academics expanded the use of originalism, and created a bullshit originalist rationale explaining why our 250 year old Constitution doesn’t allow any significant power to agencies. This resulted in SCOTUS decisions on purely partisan grounds over the last few decades that protect the filthy rich and harm normal people. The number of delay and choke points is so great that our nation is drenched in chemicals known to be toxic, and thousands of others whose toxicity, especially in combinations, is unknown.

Trump attacked the entire structure with his firings, closures, and illegal withholding of funds. District Courts tried to stop it, but the SCOTUS anti-democracy majority has dithered or rejected their decisions. Republicans refuse to push back, even to support cancer research, surely a non-partisan issue.

Trump put incompetent people in charge of all agencies and departments. They were confirmed by the Senate, often with (unnecessary) Democratic support. RFK, Jr? Whiskey Pete Hegseth? Linda McMahon? Republicans allowed Elon Musk and a small flock of ignorant coders to terminate critical programs. Without agencies, our ability to govern ourselves is wrecked.

The Judiciary

The attacks on the judiciary began after Brown v. Board. Impeach Earl Warren, screamed billboards all over the South. But it took off under Ronald Reagan, who appointed a host of ideologues to the bench, leading to his failed effort to put the loathsome Robert Bork on SCOTUS.

Republicans responded to the rejection of Bork by pushing even harder to put right-wing ideologues on the bench. George Bush the worst stopped listening to the centrist ABA on judicial nominations. Trump handed judicial nominations to the Federalist Society and to Leo Leonard. McConnell made sure Democrats couldn’t appoint people to SCOTUS. Then Trump appointed a crank, a frat boy, and an dithering academic, none of whom have evidenced any core principles other than obeisance to Trump’s dictates.

The Fifth Circuit is full of nutcases and fools, among whom I single out the odious Matthew Kacsmaryk. The Fifth Circuit refused to rid itself of single-judge districts, and ignores judge-shopping, making this lawless nutcase the most powerful judge in the country.

Then in Trump v. US . John Roberts crowned Trump king of the nation, and implicitly approved everything Trump and his henchmen have done. See, for example, the ridiculous order allowing Stephen Miller to export human beings to terrorist nations, issued without explanation, and without a full hearing. Roberts can only be compared to Roger Taney.

States

The federal system gives states a central role in assuring the health, safety, and welfare of their citizens. Historically Republicans used what they called states rights to stop federal efforts to enforce the 14th Amendment. They were generally unwilling to attack state action in significant ways. Trump has started this assault on his own.

He hit states whose policies he doesn’t like by cancelling grants, by senseless litigation, and by sending in the National Guard, the Marines and ICE thugs. One of his earliest acts was to file a lawsuit against Illinois, Cook County, and Chicago, alleging that it’s unconstitutional for us to limit the cooperation of local law enforcement with ICE thugs. In other words, we have to use our own resources to fill Stephen Miller’s gulags.

Trump demanded the Republicans pass laws, including the Big Bill, that will harm Blue states. He helps Red States damaged by his tariffs. He attacks states who don’t force colleges and universities to follow his anti-DEI policies, meaning erasing not-White people from history and higher education.

Private Institutions

The Republican war on higher education began with Ronald Reagan’s attacks on California colleges and universities. The attack was two-pronged. He packed the boards of these institutions with Republican loyalists, a philistine group who demanded focus on job training at the expense of education. Public support was reduced dramatically, forcing the system to increase tuition. This led to a massive increase in student loans, and to debt servitude for millions of people.

This two-pronged attack was immediately followed by other states, partly out of spite (Republicans) and partly on financial grounds (centrist Democrats). Republicans, ever the victims, claimed that universities were liberal and quashed conservative viewpoints, whatever those might be. The screaming got louder, and Trump used it to attack higher education a bit in his first term. All this was fomented and paid for by filthy rich monsters and justified by liars.

In his second term Trump directly attacked Harvard and Columbia on utterly specious grounds. He has made life miserable for foreign students studying here on visas, a deranged policy with no benefits to our nation. He has cut off federal support for basic research, the foundation of US leadership in most sciences and most technologies.

The Republican attack on law firms was focused on trial lawyers, a group that fought to protect working people from the depredations of pig-rich corporations. For the rest, the damage was largely self-inflicted. Firms grew to gargantuan size, taking in tens of millions of dollars. To keep that flow of money they surrendered professionalism and became servants of the filthy rich. When I started practicing law, we were bound by the Model Code of Professional Responsibility. The current weakened version of that ethical code is called the Model Code of Professional Conduct. Lawyers relieved themselves of all responsibility to society and the rule of law.

When Trump attacked, many of these behemoths were unprepared to act responsibly, and cravenly kissed the ring.

The attacks on private enterprise are smaller in scope. Primarily Trump seeks to force corporations to dismantle DEI programs, terminate support for LGBT initiatives and outreach, and similar matters. The media have self-policed rather than confront the craziness, a task made easier by their financial weakness.

What is to be done

The battlefield is enormous. Sometimes it seems overwhelming. None of us can deal with all of it. But each of us can deal with some of it. There are a lot more of us than there are of them. When we mass up on any front, we will have an impact.

I go to #TeslaTakedown. Hurting Musk is an indirect attack on Trump, and serves as a warning to the other Tech Bros. We have to keep that going.

Many of us are alumni of colleges under attack. I don’t give money to Notre Dame, even though my education there was sterling. I should have written a letter explaining why I would never contribute again, and why I removed a bequest from my will.

We can’t avoid all collaborating corporations entirely, but my family stopped using Target and cancelled our New York Times subscription. We can all redirect our spending. And then we can write letters saying we did it because they hurt our fellow citizens. Or even something fiercer.

Given the economic chaos and uncertainty, cutting spending, and front-end loading our spending, seem like sensible plans. We can point this out to others in our families and among our friends. As an example, Trump plans to increase tariffs on computers, or does he? Buy now and prepare to live with it for a few years.

Harvard and other major research universities have enormous endowments. They could open branches in Berlin, Paris, Guangzhou, Mumbai, Accra and anywhere they can find brilliant grad students. They can send their own professors, their own lab teams, and their own know-how out of a nation suddenly devoted to stupidity.

Law firms can announce plans to provide pro bono representation to people kidnapped by ICE thugs. Corporations can browbeat the Republican pols they have put in place, demanding sane economic and immigration policies. We can demand that they do so.

Conclusion

Notes: I wrote this from memory with a minimum of fact-checking. Corrections and additions welcome.

Someone should write a book about this war. Is there one I don’t know about?

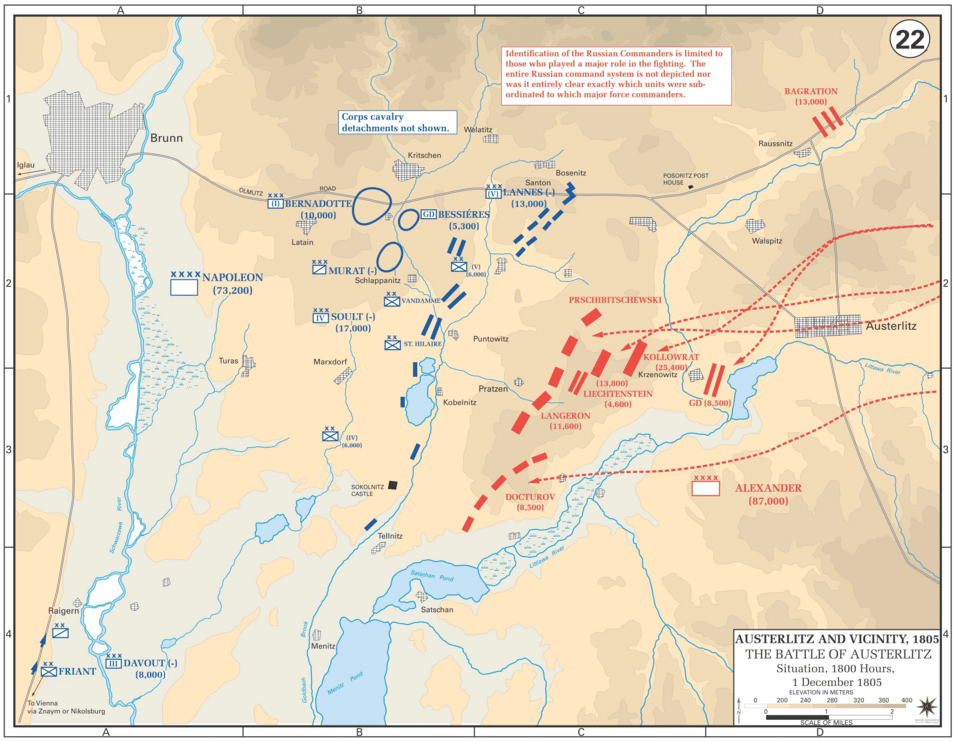

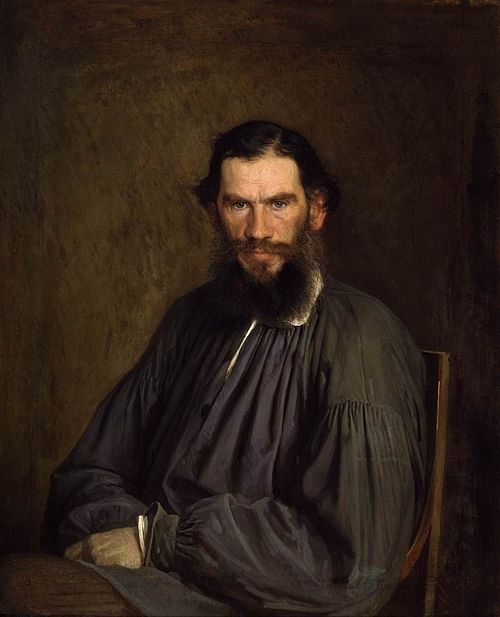

Finally: In War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy says that Napoleon was successful because he and his subordinates were able to concentrate their forces against the weakest segment of the enemy battle line. He tried to hold a large reserve to send against that weak point. That seems like a good strategy. Trump and the Republicans have spread themselves out over a gigantic battlefield. Let’s try Napoleon’s strategy.

=========

Featured image is a map of the Battle of Austerlitz won by Napoleon.