The December 2010 Black Hole in the Network Interface Closet

As I’ve suggested, I’m very interested in pinpointing when and how the Federal government first got involved in the investigation of the JSTOR downloading and what role MIT had in the Feds getting involved. While Swartz’ lawyers put together a timeline of the investigation, it constitutes grand jury material that is currently sealed (though you can be sure the content of it would have been aired during Swartz’ trial).

As I’ve suggested, I’m very interested in pinpointing when and how the Federal government first got involved in the investigation of the JSTOR downloading and what role MIT had in the Feds getting involved. While Swartz’ lawyers put together a timeline of the investigation, it constitutes grand jury material that is currently sealed (though you can be sure the content of it would have been aired during Swartz’ trial).

And while we can get a pretty good idea of how the investigation proceeded from court documents, there two periods about which I have questions: December 2010, and the day of January 4, 2011.

The timeline below shows how Swartz allegedly accessed JSTOR documents, along with the response that JSTOR, MIT, and the government took. As you can see, the investigative narrative sort of fades out for the entire month of December 2010, when Swartz had a computer hooked right into MIT’s network. And then–due to what gets vaguely described as new tools to track flows on MIT’s own network–they found Swartz’ computer. But there’s a weird lapse in time, too: JSTOR notes that Swartz is downloading again around Christmas. But MIT doesn’t go find the computer–which it has recently acquired the ability to do–until January 4. Note, too, that the indictment treats the downloads from November 29 to December 26 as one charge, and those from December 27 to January 4, as another.

That leads to January 4, 2011, when according to the public fillings, the Cambridge cops and Secret Service got brought in and–almost immediately–SS takes over the case and MIT hands over data flow materials to SS without demanding a warrant. HuffPo explained that process this way:

According to the source close to the investigation, when MIT employees found the laptop, they contacted MIT police, who called Cambridge police, where the call was then routed to a detective assigned to the New England Electronic Crimes Task Force. That detective contacted another member of the task force, Michael Pickett, a special agent with the U.S. Secret Service, who helped lead the investigation.

In addition, MIT allows SS to get Carnegie Mellon’s CERT to collect the signals from Swartz’ laptop in a dropbox; when Swartz’ lawyers first asked for CERT’s notes on that data flow, the government refused to turn it over, saying that since they would not call any CERT experts to testify they didn’t have to.

I’m wondering several things. First, what were the new tools MIT used to analyze their networks in December 2010? Where did they come from? When did they get them? Was the JSTOR download the reason they did?

And also, what kind of legal analysis did MIT go through before they just let the government into their networks?

Finally, what obligations was MIT under to file Suspicious Activity Reports to the government regarding the JSTOR downloads and when did those obligations kick in? Did MIT comply with those obligations? Did the government know MIT’s network was compromised as early as September, or not until Cambridge brought in SS in January?

To be clear: I’m not suggesting anything nefarious about this–though I am mindful of this, from the scope of the investigation MIT President Rafael Reif has ordered: “I have asked that this analysis describe the options MIT had and the decisions MIT made, in order to understand and to learn from the actions MIT took.” That is, Reif now wants to know which of the decisions MIT pursued they had legal choices to avoid.

The government’s consolidated response to Swartz’ suppression motion claims that “neither local nor federal law enforcement officers were investigating Swartz’s downloading action before January 4, 2011, when MIT first found the laptop.” Note, they refer just to Swartz’ downloading action, not Swartz (though that may just be legal particularity), so it is possible though unlikely that federal law enforcement officers were investigating other activities of Swartz before then (we know the FBI had investigated his PACER downloads the previous year).

Note: the following timeline depends on the assertions of both the government and Swartz’ lawyers. It represents alleged facts as presented by self-interested parties, not uncontested facts. Documents used include the hardware search warrant affidavit, superseding indictment, motion for discovery, pre January 4 suppression motion, January 4-6 suppression motion, consolidated response to motion to suppress, and exhibit to supplement to motion to suppress. I’ve also included Swartz’ FOIAs, as described in this Jason Leopold story, because I find some of the coincidences intriguing (see especially the timing of his request for Secret Service access to encrypted files and CERT, which I’ll return to in a later post).

September 25, 2010: Swartz logs into MIT’s network (presumably via wifi) from Building 16.

September 25, 2010: JSTOR blocks access to Swartz’ assigned IP address.

September 26, 2010: Swartz assigns himself a new IP address and resumes dowloading.

September 26, 2010: JSTOR blocks over 250 IP addresses.

September 27, 2010: MIT prohibits guest registration for any computer with Swartz’ computer’s MAC address.

October 2, 2010: Swartz spoofs his computer’s MAC address, logging in with new IP address.

October 8, 2010: Swartz logs in second computer.

October 9-12, 2010: JSTOR blocks all of MIT’s network access to JSTOR.

October 13, 2010: MIT bans new MAC address.

November 29, 2010: Beginning period for Count 5.

December 10, 2010: Swartz FOIAs “documents related to me, Aaron Swartz, as well as any documents related to any associated PACER investigation” from DOJ’s Criminal Division; the FOIA returns no documents.

December 14, 2010: Beginning of period for which MIT handed over historical network flow data relating to IP addresses related to Swartz’ laptop.

December 26, 2010: End of period for Count 5.

December 27, 2010: Beginning of period for Count 6.

November to December (probably November 29 through end of December):

The indictment explains:

During November and December, 2010, Swartz again used the “ghost laptop” (i.e., the Acer laptop) at MIT to download over two million documents from JSTOR,

[snip]

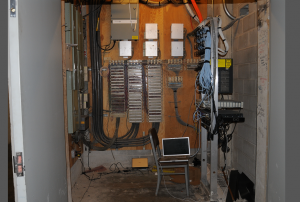

During this period, when Swartz connected to MIT’s computer network, he circumvented MIT’s guest registration process altogether. Rather than let MIT assign his computer an IP address automatically, Swartz instead simply hard-wired into the network and assigned himself two IP addresses. He did so by entering a restricted network interface closet in the basement of MIT’s Building 16, plugging the computer directly into the network, and operating the computer to assign itself two IP addresses.

The consolidated response describes:

He also moderated the speed of the downloads, which made them less noticeable to JSTOR.

[snip]

Because the hacker had modified the speed of his downloads, JSTOR did not notice his latest downloads until Christmas. Now that MIT’s network security had a more robust set of network tools, they could consult network traffic routing records and trace the IP address to a concrete physical location on campus.

So on January 4, 2011, an MIT network security analyst traced the hacker’s IP address to a network switch located in a basement wiring closet in MIT’s Building 16.

January 4, 2011 (end of period for Count 6):

The search warrant describes:

Using network tools available to MIT on this occasion, the computer was tracked back to a specialized network wiring closet in the basement of Building 16 at MIT.

The motion to suppress unwarranted searches describes:

On January 4, 2011, Dave Newman, MIT Senior Network Engineer, located an ACER netbook in a data room in the basement of an MIT building, which Newman believed was the computer being used to download journal articles from JSTOR. Timeline at 6. Newman, in consultation with Paul Acosta, MIT Manager of Network Operations, decided to leave the netbook physically undisturbed and instead to institute a “capture” of the network traffic to and from the netbook, which was done via Newman’s laptop, which was connected to the netbook and which intercepted communications coming to it. Id.; US Secret Service Investigative Report (“Investigative Report”), Exhibit 15 at 2. These interceptions were commenced without a warrant or other judicial process. At 11:00 am, Captain Jay Perault of the MIT police arrived, along with Det. Joseph Murphy of the Cambridge Police Department and Secret Service S/A Michael Pickett, who told MIT personnel that he handled computer forensics for the Secret Service. Id.; Investigative Report at 1. It was decided, “at the recommendation of Michael Pickett,” that the netbook would be left in place, with MIT continuing to monitor the traffic to and from it, and that video surveillance would be set up in the data room to assist in identifying “the suspect.”

[snip]

Neither S/A Pickett nor Det. Murphy applied for or received a Title III warrant authorizing the interception of electronic communications or were in any way authorized by judicial process to direct and persuade MIT personnel to intercept communications and other data flowing to and from the ACER netbook between 11:00 am on January 4, 2011, and the time of the seizure of the ACER on January 6, 2011.

[snip]

Newman, Acosta, and S/A Pickett, along with Mike Halsall, MIT Senior Network & Information Security Analyst, continued to physically monitor the netbook until 2:30 pm. Timeline at 7. During that time “strategy [was] determined for continual monitoring of traffic to/from the netbook.” Id. After the MIT General Counsel’s office approved the disclosure of information to law enforcement agents even in the absence of a warrant or process complying with the Stored Communications Act (“SCA”), 18 U.S.C. § 2701 et seq. (and in contravention of MIT’s published policies of only disclosing such information after receipt of such process), and at a time when MIT personnel were acting as government agents, Halsall gave S/A Pickett historical network flow data relating to two IP addresses associated with the netbook from December 14, 2010, up to that date,4 and DHCP log information for computers using the MIT network as “ghost macbook” and “ghost laptop” for time periods including September and October of the previous year.

[snip]

S/A Pickett left the MIT campus at 4 pm on January 4, and Newman waited to hear from him regarding “where to put the captured network traffic.” Timeline at 7. Thereafter, Pickett contacted the CERT Coordination Center at the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon University6 and received instructions regarding how to upload the network flow and DHCP log data to the CERT drop box. Investigative Report at 3. S/A Pickett authored an email at 6:46 pm on January 4, 2011, stating that “[t]he flow traffic is currently being uploaded to the CERT dropbox.” Exhibit 23.

On January 5, 2011, Ellen Finnie Duranceau, MIT Program Manager of Scholarly Publishing and Licensing, took notes of a conversation with Halsall in which she indicated that the netbook was “left in place to capture traffic” because law enforcement “want[ed] to find intent + motive.” Exhibit 24 at 2. Those same notes stated that it was “now a Federal case” and that everything that had been provided was done “by choice,” and not pursuant to a subpoena. Id. at 3.

The consolidated response describes:

… an MIT network security analyst traced the hacker’s IP address to a network switch located in a basement wiring closet in MIT’s Building 16.

[snip]

When MIT personnel entered the closet, they found a cardboard box with a wire leading from it to a computer network switch.

[snip]

MIT called campus police to the scene, who, in turn, brought in the Cambridge Police and the Secret Service. over the course of the morning and early afternoon of January 4th, MIT and law enforcement officers collaboratively took several steps to identify the perpetrator and learn what he was up to:

- Cambridge Police crime scene specialists fingerprinted the laptop’s interior and exterior and the external hard drive and its enclosure;

- MIT placed and operated a video camera inside the closet, which, as discussed below, later recorded the hacker (subsequently identified as Aaron Swartz) entering the wiring closet and performing tasks within it;

- The Secret Service opened the laptop and sought to make a copy of its volatile memory (RAM), which would automatically be destroyed when the laptop’s power was turned off, but the effort resulted in their seeing only the laptop’s user sign-in screen;

- MIT connected a second laptop to the network switch in order to record the laptop’s communications, a type of recording often referred to as a “packet capture;” the Secret Service subsequently concurred with the packet capture, none of which was turned over to officers until MIT was issued a subpoena after Swartz’s arrest;

- Beginning on January 4, 2011, MIT agreed to provide, and later provided, the Secret Service copies of network logs pertaining to the ghost laptop and ghost macbook between September 24, 2010 and January 6, 2011, some of which records were provided consensually, the remainder of which were provided pursuant to a subpoena to MIT.

The law enforcement team replaced the scene as they had found it. Within an hour of their departure, Swartz entered the closet and swapped out the laptop and hard drive.

January 5, 2011: MA USAO begins separate investigation.

January 6, 2011: Swartz enters the closet again, trying to hide his face from a camera, retrieves his computer, and then logs into MIT’s network from the student center to assign his computer a new IP address and MAC address.

January 6, 2011, 2:00 PM: MIT Police Captain stopped Swartz on his bike and identified himself as a police officer.

January 6, 2011, 3:00 PM: “Law enforcement” find Swartz’ laptop in MIT student center.

January 7, 2011: SS emails AUSA Stephen Heymann saying he is “prepared to take custody of the laptop … whenever you feel is appropriate. As far as I know n oone has sought a warrant for the examination of the computer” or other hardware. This email was turned over belatedly in discovery.

February 9, 2011: Secret Service obtain warrant to search Swartz’ hardware and apartment, followed by a warrant to search his office.

February 11, 2011: Searches on house and office.

February 22, 2011: Hardware warrants expire.

February 24, 2011: Secret Service obtains new warrant for hardware.

February 28, 2011: Swartz FOIAs guidelines on Secret Service techniques for reading encrypted hard disks, as well as information on CERT’s involvement in a prior case.

March 10, 2011: Swartz FOIAs “any policies, procedures, or guides for using data stored by Google for investigations, data-collection, and surveillance.”

March 22, 2011: Swartz FOIAs “Any records requests made to Amazon and any responses from Amazon in connection with any such requests. This includes subpoenas, warrants, 2703 orders, National Security Letters, etc.”

April 8, 2011: DHS/USSS provides initial responses (under separate cover) to both Swartz’ Google FOIA explaining fees.

May 16, 2011: Swartz served with forfeiture warrant for four hard drives holding JSTOR materials.

May 21, 2011: DOJ responds to Swartz’ Amazon FOIA asking for more information.

RE: “what kind of legal analysis did MIT go through before they just let the government into their networks?”

as chomsky has long noted, MIT **is** the government. maintaining the polite fiction that our neoliberal regime does not allow necessary state investment in research, it has to be justified as “military procurement” and that means MIT (ever since the early 1940’s, if not earlier). under all the cute geeky trimmings, MIT = DOD + NSA + younameit three letter organization. this widely-known circumstance (which is not unique to MIT but surely at an extreme point on the scale) leads to a chain of events which crushes a young, smart and idealistic life in its maws — with a little help from moronic prosecutors’ office. funny enough it might not have spiraled towards this snafu, if the incident had occurred at fair hahvahd down the street — but their network interface is much clunkier!

@FreddyMoraca:

[Cites needed]

Note that on January 6, it was MIT cop who stopped Swartz, but the full investigation crew arrived on scene and it was, I believe, SSA Pickett who effected the formal arrest and placed Swartz in custody by handcuffing him.

As James Carroll (among others) has observed, the Pentagon (and, hence, the federal government generally) has exerted tremendous influence over American universities, at least since 1945, owing to the ubiquity of large government “research” contracts. MIT is among the largest beneficiaries, amounting to several hundred million dollars annually.

Threats, however unrealistic, to close out such funding can be expected reliably to concentrate the minds of university authorities towards those things the federal government most wants done. The feds made such a threat, for example, when Assoc. Justice Kagan was Dean, in their successful efforts to re-open Harvard Law School to its military recruiters.

Pavlov’s work suggests that university authorities might well offer their unreserved assistance in helping federal authorities with their inquiries without the feds having explicitly to threaten such withdrawal of federal contracts.

@FreddyMoraca: Right.

Which is why I asked abt the SAR.

ANY research university, it seems, would be required to submit SARs if their networks had been compromised. There’s so many sensitive secrets at them, the govt would treat them as critical infrastructure (or as a contractor). So DID MIT tell the govt someone was downloading stuff via its network. If so, did the govt kibitz? And this was during precisely the moment the govt was trying to infiltrate the Cambridge hacking community, and precisely the moment–almost to the day–when Eric Holder declared the WikiLeaks investigation an Espionage case, giving the govt significant new powers.

And of course, MIT would feel a lot of pressure to do what the govt wanted, not least bc their funding depended on it.

But the way it gets told is MIT waits until they have the offending computer, and only THEN call in the CPD, and only via the task force does USSS get brought in.

I find that … unconvincing.

“…January 4, 2011 (end of period for Count 6):

The search warrant describes:

Using network tools available to MIT on this occasion, the computer was tracked back to a specialized network wiring closet in the basement of Building 16 at MIT…”

might “available to mit on this occassion” = “given to mit to use”, e.g., by the ss?

I’m more intrigued by President Reif’s comments. It sounds to me as if he might be upset at being left out of the loop at various points:

Abelson’s timeline will be very, very interesting, especially when laid alongside Marcy’s.

it doesn’t seem likely that this in investigation was a big mystery to the investigators.

once they were recording what swartz’s computer was recording, they would have know the content and its source (jstor).

they probably had at least a guess as to who was doing this.

they probably also knew that no serious damage was being attempted to the mit network.

they probably also knew there was little likehood of a terrorist effort.

so most of the latter part of the investigation must have focused on making an airtight legal case, not on protecting the mit network or jstor.

@emptywheel: Well said. Assuming that MIT was the law enforcement horse pulling this digital investigative cart would push credulity beyond its elastic limit.

let’s see,

the military network that b. manning accessed had, and still has, security as loose as a sieve (as one learns from persistent reading at emptywheel),

but the university network swartz accessed was viewed as requiring and needing to urgently maintain stringent network security?

let’s see,

the military network that b. manning accessed had, and still has, security as loose as a sieve (as one learns from persistent reading at emptywheel),

but the university network swartz accessed was viewed as requiring and needing to urgently maintain stringent network security?

jeralyn merritt has some related thoughts:

http://www.talkleft.com/story/2013/1/15/152428/051

@P J Evans: History – 1942 as an officer USA, my dad was at MIT training in electronics, including radar, and doing R&E on offensive RF devices. That dates the relationship exactly where FreddyM placed it. Is there any indication that the relationships have not thrived in the 70 years since?

I live about a mile from MIT (which I attended decades ago) and spent my career in University information technology, often times dealing with security issues and with MIT network staff, so I can respond to some of the issues here.

Suspicious Activity Reports. University networks, like any open network, is subject to constant – and I meant, literally, constant – attack. There was a time, a few years ago, that the reported half-life of an unpatched Windows computer on an open network – the time from putting it on the net to the time it was compromised by attack – was measured in minutes. It’s logicistically impossible to report all suspicious activity.

Confidential data on the MIT network. In the late 60s, in response to anti-Vietnam war activism, MIT decided to move all their classified and DOD research off-campus to Lincoln Labs, in Lexington MA. Out of sight, out of mind. That isn’t to say there isn’t confidential information, anything from data about corporate sponsors or even student health records available. But at the level of things the Feds are really paranoid about, they’re not on the MIT network, they’re out in suburbs.

Network compromise. I doubt that the MIT networking staff would consider this as having their network compromised. The sort of behavior you see from September through January is something that any experienced network staff – and MIT is certainly that – would have seen dozens and dozens of times, usually around the downloading/redistribution of music and movies. That JSTOR was the target would be a bit unique, but finding rogue downloaders is something University staffs know how to do. And the countermeasures Swartz was using were primitive, the minimally necessary things needed to evade the blocks MIT and JSTOR were putting up. Real network compromises, the ones that make you sweat and lose sleep, look very very different. Typically, they’re done remotely by compromising a machine with some malware, and they are hidden behind layers of proxies, making tracking them back to source extremely difficult. Think, for example, of the complexity of STUXNET. That’s a compromise. A rogue laptop? That’s an annoyance.

But the sequence you call “unconvincing” in one of your comments, Marcy, rings true to me. Tracking down a rogue downloading computer is routine. Finding that someone has placed a computer in one of your wiring closets, well, that gets outside the realm of network security and moves into physical security. And a prudent network administrator at that point calls the cops because trespassing is someone else’s problem.

I also wouldn’t read much into the upgrade of network tools. Network administrators always compain about their monitoring tools and are always looking to upgrade them. Maybe this was a routine upgrade, maybe this was an excuse to justify a costly purchase. But the fact that they

had to plug another computer into the same network closet to monitor the traffic means that they didn’t get any super sophisticated snooping tools.

Lastly, I go back to one of your original questions: What was the Secret Service doing there? If this was all pretty routine – which I’m convinced it was – why were they called in at all?

@Saul Tannenbaum:

tx.

extremely helpful.

@Saul Tannenbaum: Thanks.

@Saul Tannenbaum: That last question is the one that makes Reif’s comments very interesting to me, as does the whole picture you paint.

Routine stuff does not go up the university food chain to the president’s office. At some point, either something happened to catch the Secret Service’s attention, or someone invited the Secret Service in with a “hey, look what we found” call.

Reif’s comments make it sound as if the Secret Service were on this before he even knew about it, and that their presence changed the dynamic in some very powerful ways.

If they were called in, who called them — an IT person, University police, or someone else? On what basis? Was university legal counsel consulted first? If not, why not?

If they showed up on their own, to whom did they go? On what basis? When was legal counsel brought on board? If upper level administrators were not told immediately, why not?

Reif’s little statement has lots of questions sitting between the lines.

@lefty665:

It was his flat-out statement that government and universities are identical, with no evidence of any kind. I will agree that federally-funded research has made universities more dependent on the feds than they should ever be. (Speaking as someone who grew up in an area where the main employer was run by a university FOR the feds.)

@P J Evans: I know, I was just going to the historical factoid I could confirm. It was incidental to the question, but adds context. Those relationships have had generations to mature.

There’s certainly some general value to Fed supports that help educate people who go into non-Fed employment, and some of the R&D bleeds over to us all. But… somewhere along the line educational institutions get captured, and arguably we’re there, been there, in the engineering/science community. That ain’t so great.

OT but not really: Great article on the Swartz case at AlterNet, Marcy. Thanks for it, and this continuing examination.

FYI, updated my report to note that also on December 10 Swartz FOIA’d EOUSA for “documents related to me, Aaron Swartz, as well as any documents related to any associated PACER investigation.” Identical request he made to criminal division. The office identified 72 documents that were withheld in full.

@lefty665:

Like regulators being captured by industry… (Which was my thought.) How can it be prevented, if it’s even possible to prevent it

(There’s the other parallel: universities being farm teams for pro football and basketball. Another messy situation involving lots of money, as well as prestige for the schools.)

Where are Aaron’s activities on behalf of stopping COICA/PIPA/SOPA on this timeline? In his speech at Freedom to Connect 2012, he starts at September 2010 with a phone call from his friend Peter which he initially wanted to ignore but then got interested in.

The bill would be a devastating blow to civil liberties and the Constitution:

It was extraordinarily finessed to be inevitable:

And after improbably, impossibly the bill WAS stopped, by the most grassroots efforts of people and with the help of Ron Wyden putting a stop on COICA, giving people time to organize more – once it was dead, Chris Dodd, D-MPAA, revealed that he was the mastermind behind its presentation.

Am I the only one wondering, how good is Chris Dodd? On behalf of whom, and why? And how does he/they feel about being stopped?

OT

Chip Kelly to the Iggles. Prolly, means one of two things, 1) sanctions coming and he needed to get while the gettings good; 2) ego

If they’re no indications of sanctions, my guess is their AD

Phil Knightmakes a run at Chris Peterson@Saul Tannenbaum:

Did you see sevysmith’s comment earlier? http://www.emptywheel.net/2013/01/13/two-days-before-cambridge-cops-arrested-aaron-swartz-secret-service-took-over-the-investigation/#comment-501419

My bold. It’s not just what the SS ECTF was called in on, it’s what they were called OFF of — or were never on to begin with — that’s shocking.

@P J Evans:

sorry for my lack of footnotes!

agreed that all big research universities are “captured” by financial dependence on black budgets, but MIT is un otro veinte dolares. that’s why i referenced chomsky’s primary observations that the place has been a military farm since the ’40’s. his point is that weapons R&D allows massive, indispensable scientific keynesianism to sneak under the neoliberal ideological radar.

anyone desiring a reading list can start here:

1. The Cold War & the University; toward an intellectual history of the postwar years (edited by N. Chomsky & al., ISBN 1565840054, 1997)

2, Universities & Empire; money & politics in the social sciences during the Cold War (edited by C. Simpson, ISBN 1565843878, 1998)

3. Wallerstein, I. “Higher education under attack”. Commentary No. 324, Mar. 1, 2012. http://www2.binghamton.edu/fbc/commentaries/archive-2012/324en.htm

sure, plenty of progressives and neutrals work in the institute, but that doesn’t negate its main role as an arm of the state. also note: it’s the site of the only unregulated (because grandfathered) nuke plant in the country.

With respect to secret service involvement, I’ve taken time to read some of the original documents and I’ll note the following from the Consolidated Response to the Motion to Supress:

From the narrative, it seems that they brought in the Cambridge Police for crime scene forensics and the Secret Service for digital forensics.

It may be as simple as all that.

When it comes to this sort of thing, the Feds always have the best toys. Neither MIT nor Cambridge would be able to justify the expense of the technology needed to “image RAM”. But your neighborhood Fed would. Hence, the call to the Secret Service.

The next question would be: Why did the Secret Service end up, apparently, running the investigation? They’re the highest in the law enforcement food chain, for one. Second, think about this: You’re an MIT/Cambridge cop, and you’ve found a rogue laptop in an MIT networking closet. You’re probably worrying about not fucking this up and ending your career if you let another Bradley Manning get away. So, you defer to the Secret Service. You’re not going to get fired for that.

I don’t really see any evidence of anything nefarious here.

@FreddyMoraca: The MIT Nuclear Reactor is near and dear to my heart as it’s about a mile from where I sit typing. It is, in fact, licensed by the Nuclear Regulator Commission and is not a “plant”, it’s a low power research reactor.

orionATL on January 16, 2013 at 9:58 pm said: @FreddyMoraca:

jeez, this is great info.

tx

“money and politics in the social sciences during the cold war” – that brings to mind military psychologist jensen and his buddies and their role in american gov’t torture of terrorists – confirmed or not – in the 2000′s. mitchell, jessen and their buddies and their role in american gov’t torture of terrorists – confirmed or not – in the 2000′s.

@FreddyMoraca:

Lincoln Labs. (Big name in computing history.)

MIT ran it for the gummint, which, if they’ve been captured, is how it started.

Marcy,

Absolutely great post, great reporting.

Please keep it up on this issue!

I see my comment is in mod. I accidentally entered my gmail address incorrectly. left out the VS part.

But, why is my comment in mod?

Marcy,

Absolutely great post, great reporting.

Please keep it up on this issue!

@Saul Tannenbaum: Thanks for a lot of info and insight, but…

“…the Feds always have the best toys. Neither MIT nor Cambridge would be able to justify the expense of the technology needed to “image RAM”. But your neighborhood Fed would. Hence, the call to the Secret Service.”

“The Secret Service opened the laptop and sought to make a copy of its volatile memory (RAM), which would automatically be destroyed when the laptop’s power was turned off, but the effort resulted in their seeing only the laptop’s user sign-in screen;”

That ain’t exactly a robust effort embracing expensive and esoteric technology unaffordable by the local yokels. “Dang, foiled again by that pesky password.” Really? Gotta call in the Feds to roll over and play dead at a logon password? Isn’t hacking that an entrance requirement for MIT frosh? Nobody at MIT is capable of doing a memory dump? Pull the other one please, it’s got bells on.

Your conclusion: “I don’t really see any evidence of anything nefarious here.”

Nothing to see here folks, please move along.

@lefty665:

MIT is one of the places that I would expect to see that kind of analysis being done aas part of their engineering and computer science programs. ((Also: Carnegie-Mellon, CalTech, and Stanford.)

@lefty665: It’s perfectly plausible (to me, at least) that the Secret Service invested in some forensic tool that, say, works fine on Windows systems but can’t do a thing with Linux, which is likely what Swartz was running, or needs some hardware port that a netbook doesn’t have. And, it’s perfect plausible that that’s a distinction that escaped Cambridge/MIT police until the Secret Service guy showed up. And think it’s perfectly plausible to think “keystone cops”, not super-elite anti-hacker techno-elite cops.

And, yeah, doing a memory dump of a running computer that passes the tests for maintaining chain of custody and doesn’t disturb it in a way that’s noticeable to the owner, that’s beyond the skills of most MIT freshmen and MIT network administrators.

And let me be clear: The absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence. I said I didn’t see anything nefarious in the story so far. So, what I meant to say is: “Nothing to see here yet folks, so lets keep looking”.

@P J Evans: Saul clearly has knowledge of the local players. That makes me value the essence of his conclusion that a self protecting bureauocracy covered its butt by escalating and notifying the SS. However, he’s also clearly got technical skills, and the techie foundation for his conclusion didn’t hold up as well. Cognitive dissonance, aka WTF?, set in.

By the time they called the SS they knew who they were dealing with, what he was doing, how, and that he was of interest to the SS. It’s a little disconcerting how tightly the SS was wound in at the local level. But it’s not surprising, especially considering Mittens early support for and establishment of fusion centers. You can see the discussion being something like “Jeez guys call Mike and tell him to get his ass over here. He’ll love this”.

That may go to the question at the end of Saul’s first post: “Lastly, I go back to one of your original questions: What was the Secret Service doing there? If this was all pretty routine – which I’m convinced it was – why were they called in at all?” Also to Reif’s interest, essentially: “Who invited the SS onto my turf and turned this into a Federal case without letting me know?”.

Nefarious? Maybe not, but surely the proverbial road to hell.

@Saul Tannenbaum: From a simple “how do we solve this mystery?” standpoint, your comments are spot on. But from the “how does a university run?” standpoint, there’s still a lot that doesn’t make sense.

If you’re a university cop and you are contemplating calling the Secret Service, you damn well better also have been talking to internal university higher-ups as well. From Reif’s remarks, that does not appear to have taken place.

No university president likes it when their secretary buzzes with a message “Sir? The press is on the phone and is asking why you called the Secret Service to look at a closet on the MIT campus?” Says the president, “I called the Secret Service?” Replies the secretary “That’s what they’re telling me. Do you want to take this call?”

Not a good way to start the morning.

@Saul Tannenbaum:

I’ll agree with your comment upthread that university networks are subject to constant attacks. Knowing that, MIT’s responses were pretty cheesy, and I’m being generous.

But this remains problematic:

There’s still inadequate reason to bring in SS. Why not DHS, via one of the state’s Fusion Centers, for a preliminary assessment? Unless, of course, there were specific criteria met that triggered a SAR and in turn, a particular response from feds beyond the DHS Fusion Center.

I’m not certain that orionATL’s suggestion at (6) above that SS brought in unusual network intrusion detection tools is at all appropriate.

Based on what has been described so far, standard network “sniffing” tools available over the last decade would have worked to identify traffic. What was it that caused them to chase a particular IP or MAC address, though? There was something specific about the activity or the identity that heightened interest. (I remember one case in particular from my corporate IT days where a networked device set off a field service chase–it tied up bandwidth in a low occupancy building, pissed off users who demanded a fix. Was it something this simple, or something more complex?)

As a former IT project manager who worked on projects for Fortune 100 companies installing networks and servers, I’m puzzled by the ease of access to a network closet. MIT must have had plenty of experience with the typical pranks computing/networking geek students would try to pull–we’re talking about a crop of best-of-class here, too. Why would a network closet be so bloody easy to access in this environment? I’ve had to have registered keys signed in and out with Security Department as well as cameras and egress detection; doors were re-keyed as soon as physical keys weren’t accounted for. Why didn’t MIT have similar systems? It’s not like they didn’t have access to better technology.

MIT has a security problem, and it’s not just in its decision-making process or its network security. It’s a physical security problem. Frankly, Swartz did them a favor by revealing a weak spot in their security while not actually accessing anything that couldn’t be obtained without coughing up a registration and money to JSTOR. Now actual terrorists have some ideas about physically accessing MIT’s network and how long they have to get what they want.

It’s also this physical security breach that leaves me asking how and why SS was brought in so early. It sure looks like DHS should have been involved instead–dealing with a highly local, on-site challenge–with SS coming in only after DHS had resolved the physical security issues.

EDIT — 10:18 am —

Oh, and as for “doing a memory dump of a running computer that passes the tests for maintaining chain of custody and doesn’t disturb it in a way that’s noticeable to the owner, that’s beyond the skills of most MIT freshmen and MIT network administrators” — I don’t buy this. At all. I’ve got a young teen who’s been able to set up and manage remote virtual servers on my home computer for more than 2 years, and he’s hardly a computing/network whiz.

If MIT doesn’t have students AND network admin who can readily do this undetected, we might as well throw in the towel and start learning Mandarin.

@Saul Tannenbaum: From my response above that crossed with yours, it doesn’t look like we’re very far apart. I too have no doubt that the Feds have access to more resources than locals. I also hear you on the MIT and Cambridge cops likely level of technical expertise.

The MIT network folks were apparently along. I would expect they have more skills, if only because they get tired of getting beaten up by bright kids. At MIT I’d also expect a pretty general distain for Windows, with Linux variations being the OS of choice.

You’re also right that Firewire ports don’t show up much on notebooks any more, and that makes the process a little harder. But really, stalling at the logon screen? That means that they either were not very interested or that they did more than what was disclosed.

“So, what I meant to say is: ‘Nothing to see here yet folks, so lets keep looking’.” Nice turn, I like it! The initial SS contact may not have been nefarious, but the legs it got sure were. Therein lies the tale.

@Rayne: “If MIT doesn’t have students AND network admin who can readily do this undetected, we might as well throw in the towel and start learning Mandarin.”

Yeah, you can bet that someone at MIT has been able to quietly dump memory starting with rotating drums, magnetic core and everything since. Chances are pretty good that there are MIT grads on the list of developers of any of the tools Saul refers to, commercial or gov’t produced. Some of them may have Mandarin as their native tongue.

@lefty665: Here, I’ll tip my hand: remote, undetected memory dumps are commonly conducted by suspicious, frequently burned gamers who’ve found hackers masking as fellow gamers inserting malware into live game sessions.

By the time my kid–a pretty average kid, who shows zero interest in coding–reaches college, I bet he’ll have a lot of knowledge on this topic. MIT must be teaming with kids like this already; hell, look what Swartz could do at age 16.

@Rayne: Aren’t kids wonderful?

MIT had access to the IP traffic, packet by packet. Sounds like they also installed a “man in the middle”. It does not seem they really needed anything more from SS. As you note, they did not need UI access, they had Swartz already.

Looks like the local cops got involved because of the physical access to the wiring closet. From there Saul may have it right, they called SS to cover their butts, or to brown nose, or both. It seems there were far too intimate relations between local law enforcement and the SS. They likely knew the Feds were looking for an opportunity to bust Swartz and they provided it.

@lefty665: Once again, why SS and not DHS? If you saw somebody doing something suspicious to physical infrastructure, you’d call the cops and they’d call DHS. Why SS? Why skip the layer in the chain?

There’s something missing here–looks far too much like the Underpants Gnome business model.

@Rayne: Yeah, the whole SS getting involved thing bothers me, too. Note Marcy places the date for them taking over the investigation on January 4, 2011, just two days before his January 6, 2011 arrest. And yes, SS does have jurisdiction for computer crimes, but how he rocketed up to their attention is bothersome.

In thinking about this yesterday, I wondered if Swartz had any connection to bitcoin, since that might have been something that would bother SS if they somehow saw it as a form of counterfeiting. I googled Swartz and bitcoin and hit on this very interesting post:

http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/squarezooko

Swartz presents arguments way over my head (but I’ll bet you can follow them) on a validation system for bitcoin. The date of the post: January 6, 2011. He does say in the post that he had that idea that day, but I wonder if he was engaged in bitcoin discussions with people in the days leading up to it and those discussions got hoovered up? And if they saw him solving a big problem that might affect money supply…

I know, lots of tinfoil needed for this, but the timing is just really creepy.

@lefty665:

Remember, this was a laptop configured by Aaron Swartz. You want to break into a running laptop to image it, you look for security vulnerabilities that let you in. Don’t you think Swartz was capable of configuring a laptop that couldn’t be easily compromised?

@lefty665:

That’s not my reading of the chronology, but I might have missed something. Can you point me to a place where they identified Swartz before they found his laptop?

@Peterr:

That’s an absolutely fair point. But keep in mind, this had been an ongoing incident for months, and had involved senior Institute officials dealing with JSTOR. Could be the police were counting on others to go up the management chain. Could be that Cambridge brought in the Secret Service. Could be that they fucked up. I’m sure this will get carefully covered in the MIT internal investigation because it’s a key point where this started to go horribly wrong.

@Rayne:

“Hey, who’s that guy we had a beer with after that last cybersecurity meetup? He gave you his card and said to call if you ever found yourself over your head.” I say this as someone who was given cards by law enforcement officials after local (to Boston) cyber security get togethers for university staff. It could be that simple.

The JSTOR complaint. They were chasing excessive downloading from JSTOR and JSTOR gave them the IP address.

My snarky answer is: Please Google “MIT Guide to Lockpicking”. Strike that, it’s a semi-serious answer, as well. The other serious answer is: The MIT network is so open, you gain little with physical access to a wiring closet. At MIT, the philosophy has been that the network provides zero security and that each system on the net needs to provide its own. So, you break into a wiring closet gains you nothing in an environment where you can just plug anything in and its on the net and any interesting traffic is encrypted. That being said, you’d think they’d lock the doors to keep the equipment from being stolen by somebody off the street.

@lefty665:

The MIT network folks were the ones who called the MIT police. But there’s a misunderstanding about the MIT environment here. At the university I worked, while we had to deal with students attacking us in the 90s, in later years, they found other ways to occupy their time. I’m sure that’s true at MIT as well. And the network admins who were dealing with this are part of what’s effectively MIT’s corporate IT group. As a bureaucracy, MIT has a great number of Windows systems. Hell, it even runs Exchange for email. Faculty, researchers and students might hate it, but the business side must love it.

@Saul Tannenbaum: Let’s be clear what happened with “toys.”

MIT called the CPD who called Secret Service who called … Carnegie Mellon CERT. Because Carnegie Mellon has great toys (in fact, the Secret Service officer had to ask CMU how to use their toys).

Ultimately, it wasn’t USSS who did the forensics on Aaron’s computer. It was another research university considered, rightly or wrongly, slightly inferior to MIT.

Taking a step back:

As someone who’s been in the same sort of situation the MIT network admins found themself, the events as detailed in the material available to date can be explained by the normal human reactions of the folks involved.

That doesn’t mean there weren’t darker forces involved, just that what happened up to and through January 6th can be explained without them.

I think MIT has some explaining to do about how they let this spin out of their control. And I think the really interesting stuff about what the government was up to will come out of any investigation into the US Attorney’s office.

@Rayne: Incidentally, the door was locked but you could just lift up and open and it was opened.

It also had a homeless man’s clothes in it, and in one of the photos uploaded as evidence, there appears to be geek graffiti in it.

My guess is some MIT kids had already used this closet in the past.

Some of the court documents talk about an MIT student–whose identity is known to both the defense and prosecution but who is not charged as a co-conspirator (and charging documents make quite clear they believe Aaron either worked alone or they don’t know who he worked with) who was helping Aaron make his way around MIT. My guess is that by the time he was first charged that student testified to the GJ. My guess is that that student also knew of this closet, having used it in the past.

Just a WAG, though.

@thatvisionthing: “bank fraud” this term always refers to fraud committed on banks. There is no real investigative or prosecuting of banks or their minions committing fraud. That is how the banks make their moneys. Settlements are just legalizations of frauds already committed.

@Saul Tannenbaum: You’re right. Given what is public, the govt claims MIT, at least, did not know who they were dealing with until they got Aaron. I have my doubts about that. I have much greater doubts about whether Aaron was already on USSS’ radar or not, which may explain why CPD brought them in. But the official narrative is that they didn’t know who they’re dealing with.

But here is something interesting.

CPD gets Aaron’s laptop on Jan 6. At that point they DO know who they’re dealing with. But they don’t actually turn over the hardware for forensics (to USSS who turned it over to CMU CERT) until Feb 24 or thereabouts. In fact, USSS let the first warrant expire on that stuff. Though it did use the warrant to investigate Aaron’s house and office pretty quickly, 2 days after getting a warrant on Jan 9.

And incidentally, when they did the search on Aaron’s house and office, they apparently did not find the 4 hard drives on which he was storying the JSTOR materials. If I read the record correctly, they still have never found the MAC that was also used in the downloading.

@emptywheel:

Do we know, for a fact, that it was CPD who called the Secret Service? I ask because, if we don’t know that, I’m more than happy to ask the CPD myself, and pursue via other means if they don’t want to talk about.

But as to the forsensic analysis being done by CMU, I’m not sure what the point is. CMU might, in general, be considered inferior to MIT, but CMU, in its CERT, has resources and expertise MIT doesn’t. And, if you’re law enforcement looking to build a case, you’re not going to let MIT analyze the evidence, you’re going to get someone else to do it. If you’re an MIT network administrator, you’d happily make that someone else’s problem because you want to be caught up in the legal proceedings as little as possible.

@Rayne:

Gets back to this:

“According to the source close to the investigation, when MIT employees found the laptop, they contacted MIT police, who called Cambridge police, where the call was then routed to a detective assigned to the New England Electronic Crimes Task Force. That detective contacted another member of the task force, Michael Pickett, a special agent with the U.S. Secret Service, who helped lead the investigation.”

Look here: http://www.secretservice.gov/ectf_newengland.shtml

“With hundreds of individual partners, the task force includes nine universities in the region such as Harvard University, Dartmouth College and Babson College; a variety of federal, state and local law enforcement agencies from all over New England; and numerous private companies and associations.”

“For information regarding the next quarterly meeting of the New England Electronic Crimes Task Force, contact the U.S. Secret Service, Boston Field Office.”

“New England Electronic Crime Task Force

617-565-5640

Email: [email protected]”

and here: http://www.justice.gov/usao/ma/news/2011/July/SwartzAaronPR.html

“The New England Electronic Crimes Task Force has taken an aggressive stance in the investigation of computer intrusions and other cybercrimes,” said Steven D. Ricciardi, Special Agent in Charge of the United States Secret Service in New England. “Through this task force, the Secret Service and our partners on the Cambridge and MIT Police Departments demonstrate the importance of cooperation among law enforcement to focus resources and respond effectively to investigate and prevent this type of fraud.”

Commissioner Robert C. Haas of the Cambridge Police Department said, “The Cambridge Police Department was pleased to aid our partners at the U.S. Secret Service and MIT Police Department with this investigation. The results of the investigation reflect the importance of the inter-agency collaboration that was necessary to bring about the charges in the indictment.”

@Saul Tannenbaum: I agree that MIT had to bring in external analysis; if this was an insider threat, MIT needed to avoid a conflict of interest.

But…CERT? That’s gross overkill for a simple case of excessive downloading and spoofed addresses, a nuclear weapon for a rodent problem. We’re back into the why zone again.

@emptywheel: Nice. Really secure facility, that. But by all means, let’s roll the dice and call the SS for the next random kid using the closet.

This situation was so sloppy — what’s to say this closet wasn’t a honeypot?

@Rayne: If you’re a university network admin, you much rather involve CERT – which is part of a peer university – than, say, contract with some outside consultant. From the outside, CERT may sound like a nuclear weapon, from the inside, they’re colleagues with special expertise, someone you’re probably already relying on for security alerts and awareness.

Substantively, if you’re a savvy/paranoid type, you’re also looking to see if that excessive downloading was a smoke screen to hide something else, so, yeah, you go looking for high level expertise.

@emptywheel: I have no doubt that Aaron was on the Feds radar before January. But is there any evidence that anybody contacted Federal Law enforcement of any kind before the USSS first arrival at the network closet?

There’s another piece of background I’ve been wondering about. Bradley Manning wandered through the Boston hacker community and David House, who befriended Bradley and got deeply caught up in the Wikileaks investigation, was affiliated with MIT. If the USSS wasn’t thinking about that, they’re not paranoid enough.

Rayne, gets back to this:

“According to the source close to the investigation, when MIT employees found the laptop, they contacted MIT police, who called Cambridge police, where the call was then routed to a detective assigned to the New England Electronic Crimes Task Force. That detective contacted another member of the task force, Michael Pickett, a special agent with the U.S. Secret Service, who helped lead the investigation.”

From the NEECTF web site:

“With hundreds of individual partners, the task force includes nine universities in the region such as Harvard University, Dartmouth College and Babson College; a variety of federal, state and local law enforcement agencies from all over New England; and numerous private companies and associations.”

“For information regarding the next quarterly meeting of the New England Electronic Crimes Task Force, contact the U.S. Secret Service, Boston Field Office.”

“New England Electronic Crime Task Force

617-565-5640

Email: bosectf einformation.usss.gov”

and from the doj web site

“The New England Electronic Crimes Task Force has taken an aggressive stance in the investigation of computer intrusions and other cybercrimes,” said Steven D. Ricciardi, Special Agent in Charge of the United States Secret Service in New England. “Through this task force, the Secret Service and our partners on the Cambridge and MIT Police Departments demonstrate the importance of cooperation among law enforcement to focus resources and respond effectively to investigate and prevent this type of fraud.”

Commissioner Robert C. Haas of the Cambridge Police Department said, “The Cambridge Police Department was pleased to aid our partners at the U.S. Secret Service and MIT Police Department with this investigation. The results of the investigation reflect the importance of the inter-agency collaboration that was necessary to bring about the charges in the indictment.”

@greengiant: So, Chris Dodd, D-Countrywide…

Why was this “crime” prosecuted so crazily, even when the “victim” JSTOR refused to press charges? However the SS gets called in, reasonably or not? Who’s choosing to prosecute Tim DeChristopher too, btw? No sane person would see harm in what Aaron or Tim did, only activism on behalf of a common good, idealism personified, which is an interesting phrase to look at, I don’t think you could ever say it of a corporate person. Same for “sane person,” in the movie The Corporation they went down a diagnostic checklist and corporations met all the criteria for a sociopath. I think the idea of a common good, and activism on behalf of the idea of a common good, absolutely terrifies and enrages corporations and their stooges, D-Countrywide or __-___ or __-____ or __-____…

@Saul Tannenbaum: We don’t know about CPD. Just that interview about, and what the govt claims, which is rather vague.

My point on CMU is only a response to your claim that USSS would have better forensics than MIT bc they’re the govt and so they must. They may or may not, but ultimately it was another research U that did the forensics, and the USSS guy involved didn’t seem to know how to set up a data flow drop box with them.

@Jim White:

fascinating spot.

@Saul Tannenbaum: Right. But it wasn’t MIT who asked CERT (tho my initial suspicion was that they had provided the data tool that had found Swartz’ laptop–I now have entirely different suspicions). It was USSS.

@Saul Tannenbaum: NOW you’re getting closer to where I am.

The govt claims USG was not investigating Aaron FOR HIS DOWNLOADING before Jan 4–which I point out above.

That’s not the same as saying they were not investigating him, period. Also note my FOIA post two doors down. There is at least the possibility that he may have come up in SOME grand jury investigation between October 8 and December 11 of 2010.

Look, part of the Manning investigation pertained to who helped Manning scrape lots of data w/encryption to avoid notice. He got a software tool to help him do that in Jan-Feb 2010 in Cambridge. According to Adrian Lamo, he had already told the Feds who that was by August. In Cambridge at that time (though I have no idea if he was at the parties earlier) was someone who had ALREADY scraped massive amounts of data without being identified. So it’d be unlikely that he would totally escape their interest.

And presumably, one way to learn more about that would be to learn how Swartz uploaded the PACER documents to Amazon. That’s another thing he was FOIAing–what kind of info the govt got from Amazon in that investigation. And that’s something the GJ in this case was investigating too.

I’m fairly sure they used the GJ to investigate if he had ties to WikiLeaks, and that’s what his lawyer was trying to learn about in his discovery motions.

@emptywheel: About tracking down rogue downloaders:

I think you may be overestimating the specialness of the tool needed to track down Swartz’s laptop.

That information, once you have the MAC address, is queryable from the managment interfaces of the network infrastructure. But making those queries requires either network management software (big bucks) or writing your own tools. Where I worked, we wrote our own, because it was more interesting to the staff involved and, internally, nobody priced out staff time the same way they would for a purchase.

So this could be how the meeting went:

Manager: So how’s it going finding out who’s screwing JSTOR?

Network Admin: We can’t find the machine because we don’t have the capability to query the switches in real time.

Manager: Why not?

Admin: Because your predecessor thought that was network surveillance and we don’t do that here.

Manager: That’s why he’s my predecessor and no longer running these meetings. Do what you need to do.

That’s my speculation, based on what I know about how MIT’s Information Services& Technologies has changed over the past few years. They’ve gone from a group run by someone with faculty rank to a group run by a corporate manager and policies have been changing with that change in focus.

In the background to this is CALEA – the Communications Assistance to Law Enforcement Act. Universities have been having internal struggles over how to interpret this for years. On one side, you have the risk averse, insisting that you need to be able wiretap your network and identify who’s on it. On the other side, you have open network/academic freedom types, who think this is turning universities into agents of the state.

See, for example: https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/csd4355.pdf for MIT’s comments to the FCC about CALEA. Or this, from an MIT network admin’s presentation to his peers: http://web.mit.edu/network/camp/SecCamp-Calea.pdf

The signer of first document is no longer MIT’s VP for Information Technology. That post does not exist and has been replaced by a corporate manager. And the home page of the author of the second document notes that he “formerly managed MIT’s presence on the Internet”.

@Saul Tannenbaum: THanks for that MIT background. It’s helpful.

I’m not suggesting anything about the tool–I’m not making a technical comment. I’m making a point about the language used. Even down to the “available to MIT on this occasion.” And also a point about the delay between Christmas and Jan 4 in finding it. Add that to other interesting timing details, and I thikn there is something about the tool, though I make no assertions about what that might be. I have my suspicions. But I am not there yet.

Either the stuff on JSTOR wasn’t sensitive, or it was.

Either the MIT network was wide open, or it wasn’t.

Either the technology used to download/store info was wasn’t highly specialized, or it was.

Either the situation wasn’t special enough to merit SS & CERT, or it was.

There’s far too much flip-floppery about this. I just don’t see how anything laid out *so far* merits the involvement of SS or CERT, even though they were called in.

A college-aged young person using pretty basic networking admin skills downloads a bunch of academic documents otherwise available for purchase. We’re not seeing SS or CERT get involved every time some student downloads content at scale at other public research schools, are we?

@Rayne:

The stuff on JSTOR was academic papers.

The MIT network was wide open.

The tech used seemed to be a python script and open source software.

But…

You had a physical intrusion into MIT by someone who was evading – for months – MIT’s efforts to block him.

That’s special.

Any network admin who discovered something like that would call law enforcement, and stand back when your campus cops called the local cops for crime scene assistance. And when the local cops show up with someone from the local Electronic Crimes Task Force who happened to be from the Secret Service, you’d back away even further.

And, no, we’re not seeing SS or CERT involved in mass downloads, but you can be sure that the MPAA/RIAA would love it if folks with badges and guns responded to events like that.

@emptywheel: There are two words that explain the Christmas/January 4th gap: winter break.

I don’t know if MIT formally closes between Christmas and New Years, but certainly students are gone and classes don’t meet. Universities are ghost towns during that time.

I confess not to have followed the Bradley Manning evidence carefully at all, so if you can point me to specifics about him and Cambridge, I’d appreciate.

• The stuff on JSTOR was academic papers. >> No big deal, all research docs for sale even if based on publicly funded research, and all critical documents stored at Lincoln Labs–not JSTOR/MIT. So why the “badges and guns”?

• The MIT network was wide open. >> As indicated upthread, the network was under attack all the time. Why didn’t they have more sophisticated protections -OR- more sophisticated detection tools? Or did they?

• The tech used seemed to be a python script and open source software. >> This is a web-wide standard. Far from quantum physics exotica.

• “a physical intrusion into MIT by someone who was evading” them for months >> They had a homeless person’s clothes in the same closet, and indications of other unauthorized users in the closet, but they don’t get all yanked up, “badges and guns,” until somebody elects to persistently download academic documents available for sale?

As for MPAA/RIAA: they don’t have standing here. They may think they own all intellectual property, they may think they are going to call all the shots. But they didn’t call SS or CERT, and the downloaded materials weren’t MPAA/RIAA member-generated content. (And I’m getting really tired of the public failing to tell those assholes at MPAA/RIAA their business model is dead, find a new one.)

@Rayne:

The MIT network philosophy was: never trust the network. This was deeply ingrained into the culture but was also instrumental in keeping the network open. If you were going to put a computer on the network, you should expect it to be attacked by anybody at any time. If that’s your posture, who cares what folks plug into your network? You’ve warned everybody already. For those of us in the Boston university IT community, even those of us who believed deeply in open networks, this posture was extreme. But that was the charm of MIT.

As for the network closet, you’re a network geek, you find a place that’s got a strange laptop and the clothes of a homeless person. You call the cops for your own personal safety. It’s not your job to confront anyone who returns for the laptop or clothes. That’s what I would have told my staff and I don’t think it’s any more complicated than that.

To me this seems a bit like the time that Cambridge police arrested Henry Louis Gates for breaking and entering his own house. Except nobody died that time, did they? Secrecy.

Defense was going to argue that MIT has similar downloads all the time.

@Saul Tannenbaum:

One of Swartz’s early lawyers stated that MIT was the holdout (in contradistinction to JSTOR) to allowing Swartz to obtain a plea agreement early on. Whether or not that deal would have been acceptable to Swartz, I wondered who at MIT had the power to make those decisions (if MIT’s president was not the one calling the shots). I assumed it would be an MIT lawyer but your comment:

“what I know about how MIT’s Information Services& Technologies has changed over the past few years. They’ve gone from a group run by someone with faculty rank to a group run by a corporate manager and policies have been changing with that change in focus.”

makes me wonder whether a ‘corporate manager’ would have the authority to refuse a plea deal.

I also wonder whether that dynamic even existed if the Secret Service was the group running the investigation and making the arrest.

Thanks for the timeline, emptywheel. (FYI, spell check/autocorrect keeps adding a space between empty and wheel. Reminds me of a few years back when when Obama was running the first time for US President, Microsoft Word used to autocorrect ‘Obama’ to ‘Osama.’ That dictionary has since learned the new word).

Minor detail I wonder about: Swartz’s laptop was in a cardboard box that had a wire coming out of it (presumably a cable to connect it to the server). There is no mention about a second wire (i.e., A/C adaptor), so did the box cover an electrical socket? or was Swartz relying on battery power of the laptop for massive downloads? He’d have to return with a new battery frequently, no?

Or can the laptop draw power off the server?

Another question. One of Swartz’s lawyers mentioned that the prosecutor threatened the lawyer (that may not be the correct technical term) over the way the lawyer handled the prosecutor’s demand for the 4 hard drives. I didn’t understand the interaction or why the prosecutor felt the lawyer was acting improperly.

@emptywheel: I, for one, would love to see that discovery information. I hope that, once everyone involved has gotten past the immediate grief, they make everything available.

@pdaly: In universities, the big divide is usually between the “business” side, and the “academic” side. I’ll speculate that all the decision making about what to about Swartz was done on the business side: the lawyers, the folks who sign the contracts with JSTOR, etc. No one there would have had the interest or motivation to let Swartz off lightly. The academic side – the folks who believe in the academic traditions of open inquiry and who’d believe in the MIT ethic of protecting a tansgressor like Swartz – they, I’ll speculate again, were left out of the loop. And, piling on the speculation, that’s why the internal investigation is being run by an academic.

Speculation aside, we’ll know all about this once Hal Abelson has done his report.

@Saul Tannenbaum: I would hope so. But a lot of it is GJ material, so by definition not legally FOIAble.

If Issa is serious about his investigation, he could get it (though Heymann/Ortiz would probably have to agree). I doubt he’ll do that though. When Waxman investigated the Libby case, he didn’t even look at the trial record, much less the GJ material. He tried to get Cheney/Bush interviews, but they were not GJ material (except the secret second one from Cheney that he ‘fessed to in his book, btu then no one knew about it at the time). But he didn’t even persist to get that: CREW got that.

@Saul Tannenbaum: Did you see that some Anon guy polled ~35 profs on whether they supported Swartz and most did not?

Most computer guys are not as JSTOR dependent as social sciences/humanities/traditional sciences, but still, if I lost JSTOR access at the wrong time for a week I’d be pretty pissed.

Don’t know if this was the only example, but govt revealed this in an early discovery letter:

@emptywheel: The other thing that might be effecting those professors is that, to the Open Access movement, JSTOR is hardly the worst actor. It is, after all, a non-profit consortium. The for-profit publishers – Elsevier, Springer – are far more problematic and are subject to active boycotts from some academics.

I’d also be very curious about the age of the professors. Open Access is very much a generational thing. Old faculty, who’ve spent their careers building a CV of peer-reviewed articles in traditional journals, have a hard time letting go of a system that’s defined their professional success. Younger faculty, those “born digital”, seem to get it intuitively.

@emptywheel:

That’s, ah, interesting.

That’s how rogue downloading usually goes. It gets reported, you track it down, block it, and you never hear about it again. Having gotten caught, the perpetrator is mostly interested in not being identified.

More interesting is whether MIT did anything to track back who compromised the virtual machine. On the one hand, compromises can be so routine that you just play whack-a-mole, just take the machine off the net and make whoever created it rebuild it. On the other hand, compromising a machine in order to download journal articles, that’s an anomaly. Normally, a compromised machine ends up running some standard malware, and used for anything the compromiser wants: DDOS, spam/phishing, taking down your local uranium centrifuge. So, downloading journals should raise an eyebrow. Or, if you’re a tired network admin, maybe it’s “Oh, it’s only downloading journal articles, not part of some ‘bot army, let’s move on to the next mole.”

I hope the MIT internal investigation gets into this stuff. That’s the other way it can all come out without having to deal with grand jury secrecy.

@Saul Tannenbaum: well, I don’t really see how you can logically make the leap from MIT, Cambridge Police, Secret Service. Even if that task force (Electronic Crimes?) had a Secret Service agent embedded, why wouldn’t they call in the FBI? Are you implying that the Secret Service guy just happened to be the one who responded to the call? Moreover, if this fell into the jurisdiction of that task force, I’m sure they had FBI agents assigned as well.

Secret Service actual jurisdiction is quite small [limited] and they certainly aren’t the “go to” agency for this type of computer/hacking investigative expertise.

@emptywheel: Jeebus. IEEE is a key driver behind electrical and electronics standards globally. Any of their content should be wide, wide open for this reason, although once again they have a bunch of journals/publications behind paywalls to provide an income stream. Gotta’ pay the pricey rent on their NYC office, after all.

See their Wikipedia entry.

@Stu Wilde: Had an exchange on Twitter w/Kroll’s tech security person, who said Boston USA prefers to work w/USSS on tech investigations, though he originally thought it was weird too.

@Stu Wilde: I’m not making a logical leap at all. I’m saying that it’s perfectly plausible to me that, rather than thinking about jurisdiction and institutional scope, the decision was made out of very human, very expedient reasons. As a Cambridge resident and local blogger, I’m putting together my list of questions for the Cambridge Police Dept., this being the core of it. But in my experience of incidents like this, you have an awful lot of decisions being made instinctively – out of fear, adrenaline, and what feels comfortable – rather than a rational consideration the issues.

@emptywheel: Don’t forget that the US Attorney in Boston is prosecuting Whitey Bulger, FBI informant, and has prosecuted various FBI agents and supervisors, over that fiasco, Can’t imagine that helps with cooperation.

@Saul Tannenbaum: Yep. That’s precisely the explanation Kroll guy offered for the preference to work with USSS.

@Saul Tannenbaum: i understand your perspective, and i’m not trying to beat a dead horse, but to me (and maybe this is my lack of specific experience in this arena) it is not an intuitive response for Cambridge PD to reach out to the SS on an issue like this. There are always command lines and jurisdictional considerations. This wasn’t a life or death emergency. The FBI [and there are other governmental niche organizations that do cyber investigations] seem a much more logical choice.

Given Swartz’s numerous FOIA requests [touching very high viz political issues and his persistence in questioning the “official narrative,” I find it all too convenient for this investigation to involve the SS which rolls up under Treasury but is [obviously] in very close proximity to the WH.

P.S. I can understand why the SS would be present in some fusion cell or task force set up for investigating cyber crimes, etc. — given their mandate, they would take the lead when the subject involved financial institutions, counterfeiting, currency, etc. Here, as far as I’ve read, we’re talking about unlawful downloading of scholarly journal articles.

@Stu Wilde:

Look here: http://www.secretservice.gov/ectf_newengland.shtml It’s an eye opener (at least to naive me).

The connection with the locals is intimate, convenient, and intentionally that way. I think Saul’s been right on this, local cops covering their butts and, my addition, brown nosing. It’s a twofer and easy. MIT does not have to do anything but stand back and let it happen. For them what better way to start the new year than by clearing the decks of an old annoyance without lifting a finger?

“With hundreds of individual partners, the task force includes nine universities in the region such as Harvard University, Dartmouth College and Babson College; a variety of federal, state and local law enforcement agencies from all over New England; and numerous private companies and associations.” Curious they don’t list MIT, but they’re certainly not excluded.

Think also of one mechanism, among several, someone might choose to coordinate the nationwide attack on Occupy (or any other rabble/dissent) if they had the resources. Can you say “Thank you” to Turbo Tax Timmeh?

re clearing the decks above. It’s not unreasonable for the the MIT net admin staff to begin to feel institutionally or personally affronted. It’s one thing for someone to use/abuse an essentially open network; it’s pretty cheeky to blow off net staff attempts to control their system while squatting on their real estate and physically hanging hardware on their lan.

Doesn’t mean I’m unsympathetic to Swartz, or not horrified at what the Feds did to him. Just that we can see some very human reactions that got legs, perhaps with considerable SS forethought and encouragement.