Problems With The Standard Story Of The Revolutionary War And The Constitution

The standard story of the origin of our nation tells us that the Declaration of INdependence asserts that all men are created equal and naturally endowed with certain rights including the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that the Revolutionary War was fought to uphold these principles; and that the principles are instantiated in the Constitution. We didn’t always live up to those principles but we’ve always worked towards them, and we get closer all the time. P. 9 et seq. In the first post in this series, we saw that the Declaration doesn’t fit well with the standard story. What about the Revolutionary War and the Constitution?

The Revolutionary War

Roosevelt doesn’t think there was a single cause for the War.

Different people sought independence for different reasons, and likely they sometimes said what they thought would advance their cause rather than what they truly believed. History requires interpretation, and a claim to possession of the one singular truth is a hallmark of ideology. P. 55.

The Declaration explains the decision of the Colonists to throw off English rule. It claims that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. The Declaration complains that the King cut off trade between the Colonies and the rest of the world. It claims that the King ignores the laws and even the courts of the Colonists. The King attacks the Colonies directly, keeps a standing army in the Colonies, and quarters troops on the population. The King imposes taxes on the Colonies even though they are not represented in Parliament. The King stirs up the “merciless savages” to attack and murder the Colonists. The only reference to slavery is oblique: the King “… has excited domestic insurrections amongst us….”

No doubt one or more of these claims were a factor for some of the Colonists. The principle of consent itself may have motivated some of them. The listed claims may have motivated others. Perhaps some were motivated by a desire to bring about equality or at least to end slavery (Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin, for example.) Roosevelt points out that protecting slavery may have brought others into the war:

There isn’t much evidence supporting the idea that slavery was an issue. Of course just as people say things they don’t believe to advance their cause, others may keep quiet about their actual reasons if they would hurt the cause. There was little to be gained by saying we’re rebelling because we want to enslave people. Roosevelt suggests that

… for some of the Patriots, a desire to preserve slavery was one reason—and maybe a strong one—to declare independence[.] On its face, this is pretty plausible. Just as it seems unlikely that northern Patriots had slavery at the front of their minds, it is unlikely the southern ones didn’t have it at least at the back of theirs. P. 53.

In any event it’s hard to argue that the War was fought over the principle of equality for anyone except white men and especially white men with property. A telling detail: the British offered slaves freedom if they fought for the King. After the War the Colonists demanded the return to slavery of those people. The British refused.

Nor was the Revolution fought to advance a broad principle of equality. Roosevelt says that the statement that all men are created equal is a reference to the fictional state of nature assumed to exist in the beginning. The broader concept of equality would have to wait for the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789. It asserts that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” This is a statement about real people living in real societies, not imaginary savages in the wild.

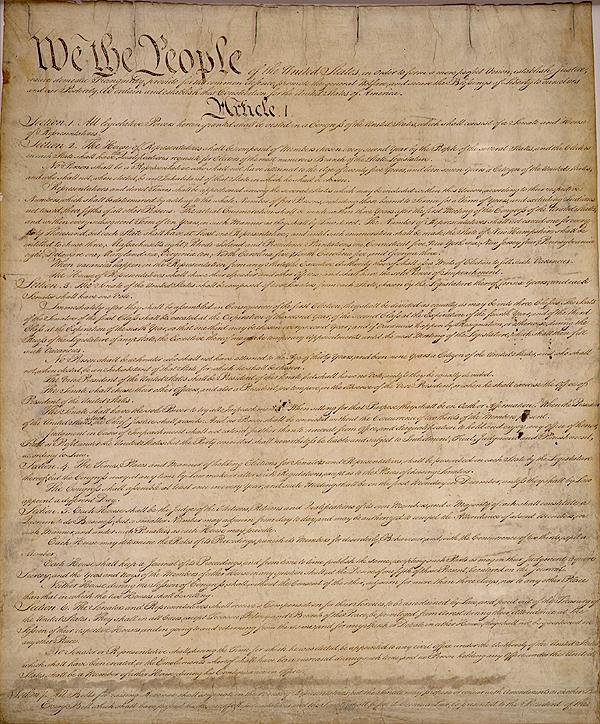

The Constitution

The Constitution was necessary because the Articles of Confederation failed to create a strong enough central government. The states were fighting among themselves, refusing to adhere to treaties, imposing trade restrictions and refusing to pay the debts incurred in the Revolutionary War. The preamble states the reasons for adoption of the Constitution, starting with “to produce a more perfect union”, and ending with “to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” Roosevelt says that the chief goal of the Constitution was unity, with liberty at the bottom of the list.

If the Constitution were actually about individual human rights, it would include provisions that protected the rights of individuals. It doesn’t. The Founders Constitution restricts the Federal Government’s right to intrude on the specific rights in the Bill of Rights, but the states were free to intrude as much as their own constitutions allowed. It took the 14th Amendment to change that, and to make the Federal Government the guarantor of individual rights against itself and against the states.

As to slavery, there are three provisions that directly or indirectly support its continuation: the Three-Fifths Clause, a provision barring the Federal Government from ending the international slave trade until 1808, and the Fugitive Slave Clause. Each of these cemented the power of the slave states.

The Three-Fifths Clause redressed the population imbalance between the slave states and the rest, allowing slaves to be counted at ⅗ of a person for purposes of calculating the number of Representatives allocated to each state. It worked with the provision giving each state two senators to insure a balance in the legislature between slave and free states. In addition it gave the slave states an edge in the Electoral College with respect to population. Thomas Jefferson would have lost the election of 1800 to John Adams without the Three-Fifths Clause. Ten of the first 12 presidents were slavers. P. 76.

The prohibition on ending the slave trade before 1808 enabled slavers to rebuild their holdings by importation after losses in the Revolutionary War. The British offered freedom to any slave who fought for the King, and thousands of slaves accepted this offer. Others escaped their bonds. The Colonists demanded return of these escapees, but the British refused. The outcome is that slave population rose from 697,497 in the first census of 1790 to 1,191,362 in the 1810 census.

The Fugitive Slave Clause says that slaves who escaped to a free state did not gain their freedom, and that the free state was required to return them to their enslavers. This was a big win for the slavers. Under the Articles, each state determined how it would treat slaves in their territory; in fact that rule remained in effect as to slaves brought to free states by their masters. The Constitution stripped the States of their right to decide the question of slavery as to escapees, which today we would call a violation of States Rights.

As South Carolina delegate Charles Cotesworth Pinckney boasted upon his return from the Constitutional Convention, “We have obtained a right to recover our slaves in whatever part of America they may take refuge, which is a right we had not before.” P. 79.

Discussion

1. The standard story has a central place in our understanding of ourselves as Americans, regardless of other political views. Other nations have national stories, but it seems like we put a lot of emphasis on this story and the two documents, more than citizens of other countries do.

2. One consistent element of our self-image as Americans is that we consent to our government. In prior posts I’ve discussed the theoretical idea of the social contract. That’s not what I’m talking about. We believe that government only works if people consent to it.

Apparently that belief is not shared by a substantial of Republicans today. In this they are like the secessionist Confederates, as Heather Cox Richardson shows.

“We do not agree with the authors of the Declaration of Independence, that governments ‘derive their just powers from the consent of the governed,’” enslaver George Fitzhugh of Virginia wrote in 1857. “All governments must originate in force, and be continued by force.” There were 18,000 people in his county and only 1,200 could vote, he said, “But we twelve hundred . . . never asked and never intend to ask the consent of the sixteen thousand eight hundred whom we govern.”

3. Regardless of what Jefferson meant with the phrase all men are created equal, today we flatly mean that we’re all born equal, we’re all entitled to equal rights, and that one function of government is to guarantee that equality.

Apparently that belief is not shared by a substantial number of Republicans.

Yep.

The Republicans are child-like.

Not to know what happened before one was born is always to be a child. — CICERO

“But we twelve hundred . . . never asked and never intend to ask the consent of the sixteen thousand eight hundred whom we govern.”

Points for honesty.

And yet can there be any doubt that this statement would serve as much greater inspiration for the currently elected Republicans than any flowery phrases found in the Declaration of Independence?

Imagine their internal agony at having to deal with all that crappy election nonsense at nearly every level of government, and how much salve to their tormented egos the Federalist Society must be. The embattled Republican solons in the Tennessee house were pretty clear about this: they see themselves fighting a war for the Republic which will be lost if they themselves do not win.

L’etat c’est moi.

TN. Divine right

[Welcome back to emptywheel. Please choose and use a unique username with a minimum of 8 letters. We are moving to a new minimum standard to support community security. Because your username is far too short it will be temporarily changed to match the date/time of your first known comment until you have a new compliant username. “Aj” is also your fourth username out of four comments — you used “Ada Brownlee,” “aj” and “Xxx” previously. Using more than one name is sockpuppeting and not permitted. Thanks. /~Rayne]

Thanks for this fascinating analysis! I wasn’t born in the US but I have lived almost 50% of my life here. It strikes me that in this country people are animated by mythical beliefs about rights and values supposedly found in the foundational documents. But the truth is that many of these rights and values were never formally encrypted in these documents. Sure, it is swell that we are all created equal. Sounds self-evident, except that the men who wrote this were just fine that black people or women were excluded. In a country that likes to think of itself as a democracy, it is shocking to me how the right to vote is treated as some subsidiary plaything. I could go on. The US is frozen in time with antiquated documents and unable to fix itself. The ambiguities and omissions of the US constitution are such that one cannot be assured of anything with the extremist SCOTUS now. Many of those things were never formally fixed (let sleeping dog lie…) until it all blows in our faces today.

Thanks for putting in the link at the top of your article with refs to your earlier posts because when I started reading your article here I was puzzled by the mention of a ‘Roosevelt’ and pages to some work!!! Teddy? FDR? Huh? But now I see you are referring to Kermit Roosevelt & his book (The Nation That Never Was: Reconstructing America’s Story), plus Foner’s book (The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution). They sound like good works to add to my reading list. Thought-provoking, for sure. Wish the Repubs would get up to speed and take note. Again, thanks for your contributions to this site.

I’m sure the books are thought-provoking, however the ‘Roosevelt’ quotes are still very deferential to history, and when diving into the intent and motivation of people from the 1770s.

It seems to me (as a distant Aussie) that the war against British colonial rule was overwhelmingly motivated by (a) securing slavery (they could detect the whiff of Abolition right across the Atlantic), (b) entrenching the privilege of the colonial, landed, ruling elites – by making them top of the food chain, and to a lesser extent (c) a revolt against the view of the British ruling elite that the colonials simply had no rights that London didn’t want to allow.

How much better would an alternative course have looked? Wait a further (say) 50 years at most, bring about the peaceful and orderly demise of slavery by making importation illegal, as a start), and then a mutually agreed independence, negotiated in London and say Philadelphia. So not only would the War of Independence have been avoided, but so too the Civil War, Jim Crow, and a century of unresolved racial ugliness right up to today’s MAGA lunacy.

A parliamentary system could have been devised, rather than the very weird creature devised in the Constitution. The other option could have been (say) six big regions that became independent nations in a loose continental confederation, rather than 50 states under one unwieldy central government. It’s fun to speculate.

“Just as it seems unlikely that northern Patriots had slavery at the front of their minds, it is unlikely the southern ones didn’t have it at least at the back of theirs.” (Roosevelt)

Alexander Hewatt, South Carolinian, 1779:

“As all white men in the province, of the military age, were soldiers as well as citizens, and trained in some measure to the use of arms, it was no difficult matter to complete the provincial regiment. The names being registered in the list of militia on every emergency they were obliged to be ready for defence, not only against the incursions of Indians, but also against the insurrection of negroes.” [lack of capitalization in original.]

Hewatt, Alexander. (1779) An Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of the Colonies of South Carolina and Georgia, 2:245. Alexander Donaldson, London.]

The language of the 2nd Amendment was understood explicitly by southerners (Virginians and Carolinians) to refer to “slave patrols” and complemented South Carolina’s non-negotiable demands for a fugitive slave clause in the Articles, which in turn was incorporated in the Constitution by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.

Many backers of unrestricted gun rights today have similar racist motives.

One thing that’s rarely mentioned is that about a third of the people living in the to-be-US didn’t care about it. Another third supported the royalists/loyalists. (One of my ancestors paid a hefty fine – 10 pounds, in 1776-77 – for being a non-jure. He hadn’t take the oath of allegiance in PA.)

As a matter of fact (if I recall correctly) it was the followers of Daniel Shays (at least in Massachusetts) balking at the ratification of the Constitution which led to the Bill of Rights being written and tardily appended to it.

Shays’ Rebellion, like the Whiskey Rebellion almost a decade later, was more about the economic rights of poor colonists, in opposition to the landed and monied elites. In Shays’ case, it pitted the colonists in central and western Massachusetts against the Boston elites. It was used as a cause celebre by backers of the stronger central govt inherent in the Constitution.

Well, fudge. I cannot find the reference in any of the books on my shelves. Considering my age and the erosion of memory by medications (including chemo) I might have simply made it up.

Certainly, the former Shaysites continued to oppose Federalism for a number of years. Proof of this can be found in the rather late ratification of the Bill of Rights by Massachusetts in 1939. (See Wikipedia article on “Bill of Rights” for year of Massachusetts ratification.)

William Hogeland wrote several books about the period, including The Whiskey Rebelliion, which might be worth your checking out. His book about the Declaration – which discusses the contribution of now obscure figures like Herman Husband to the unanticipated approval of the Dec of Independence in a state where there was vehement opposition to it – is also especially worth considering in addition to Ed Walker’s excellent discussion given here.

Hogeland’s books are well-researched and well-written. His work is what the academy calls “revisionist,” meaning outside their usually tepid norms, and that he rocks the boat from the perspective of power holders, then and now. David McCullough’s work is safer and more genteel.

Between the Articles coming into force in 1781 and the ratification of the Constitution in 1787, there were many, many lumps in the oatmeal. The Vermont contingent, for example, made a royal pain in the ass of itself all through the discussions, particularly concerning the slavery question as the constitution of the Vermont Republic had outlawed slavery in 1777. The Vermonters’ strategic geographical position between New York and New Hampshire (both of which had been trying since 1764 to unilaterally annex the Vermont lands), combined with the Vermonters’ favorable disposition toward Quebec, made it vital in Philadelphia that the Thirteen somehow make nice with the Chittendens, Olcotts, & Brighams (not to mention the elder of the Allen brothers — truly a loose cannon who, after taking Ticonderoga in May 1775 attempted to take Montreal in the September of the same year, with less than spectacular results.)

Look at Rhode Island. The promise of the Bill of Rights and the threat of big tariffs where what got them to ratify – in 1790.

Unclear what is meant at end of discussion point 1. “…more than citizens of other countries do”. Do you mean they don’t put as much emphasis on our national story as we do or they don’t put as much emphasis on their own national story as we do on ours?

My two cents: The US, like other colonial states where the colonists wanted to stay, doesn’t have a mythical folk culture that it can draw on for developing a sense of nationalism. Nationalism as a unifying force was a necessary feature of the process of industrialization as the state required a large workforce where people spoke the same language and were prepared with generic training that could be adapted to factory work. The folk culture used by older states was more-or-less just an appropriation from myth; there was no necessity for it to be genuine, but it did have to be real enough to get the people to accept it as a step toward unification.

In the US, that purpose is served by the foundational documents since they had rebelled against the holders of the most likely folk culture that could have served the purpose. As an aside, one can see how fortunate the US was to avoid the excesses of nationalism based on a mythical folk culture (but now that the US is old enough to have it’s own mythical folk culture, perhaps it won’t escape the trap after all).

Tho books that may help:

“Albion’s Seed”, by David Hackett Fischer, helps in understanding the various regional cultures that the US has had from the start, and why we still have problems.

“Decision in Philadelphia”, by Collier and Collier. It’s about the Constitutional Convention and the personalities involved.

Ken-

I agree with you that a national myth based on ideals (and whatever may have been in the heads of some of the founders, the understanding of the ideals has certainly improved over the centuries) is preferable to other types of national myths.

Living in Central Europe, I find the nationalism quite sad in many ways. Reality here is almost more a rural culture and an urban culture. If language could be “hidden”, a group of e.g. rural Slovaks and rural Hungarians would have much the same lifestyle (making alcohol, pig slaughtering as family and even community event, for instance). Cities have mostly historical centers, churches whose design reflects the century in Europe more than the particular nation, cafe-culture, etc.

I’ve been heartened to see, across the border, that Ukrainians often talk about freedom as a key part of their struggle, and while the Ukrainian language is cemented in law as the official language (a reasonable act given the weaponization of the Russian language and culture by RF), they overall seem to be glad of ethnic minorities (and this is also reflected in their Constitution).

From this idealist,

A lot of these 18th century ideals are veins of gold embedded in shibboleth rock. As history unfolds this rock (ore) is slowly refined and purified through the fires of war.

97 Native American vs US wars listed in Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_American_Indian_Wars

List of all wars involving the United States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_involving_the_United_States

What is redeeming for the United States is that the United Nations is here, born in post WW2 San Francisco and is growing up in New York City. The UN is now spreading hope for the whole World and not just one nation or region.

https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/04/1135672

From this idealist,

A lot of these 18th century ideals are veins of gold embedded in shibboleth rock. As history unfolds this rock (ore) is slowly refined and purified through the fires of war.

97 Native American vs US wars listed in Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_American_Indian_Wars

List of all wars involving the United States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_involving_the_United_States

What is redeeming for the United States is that the United Nations is on our soil, born in post WW2 San Francisco and is growing up in New York City. The UN is now spreading hope for the whole World and not just one nation or region.

https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/04/1135672

“today we flatly mean that we’re all born equal, we’re all entitled to equal rights, and that one function of government is to guarantee that equality.”

That’s a basic truth that creeps like Charles Murray, Andrew Sullivan, and a bunch of the fake brainiacs of Bari Weiss’s Intellectual Dark Web have been working overtime to undermine.

As people like Jamelle Bouie and Adam Serwer keep pointing out, the caliper-wielding phrenologists keep trying to reignite the racist theories of the 19th Century misinterpreters of evolution so that they can create a permanent underclass denied basic equality under the law.

They also think that women are incapable of managing their own lives.

More likely that they don’t want them to run their own lives. It’s more fun to do it for them, since all the choices and priorities are yours, not theirs. Parallels with slavery intentional.

Another perspective is that the Revolutionary War was the third English Civil War, but was fought overseas.

There had been wars, on and off, in England from the 11th to 17th centuries.

Maybe England has had internal peace since the 17th century, because their habitual war problem had moved to America.

The Smithsonian recently noted that the American Revolution was only one front in a world war: “the 18th-century fight for independence fit into a larger, international conflict that involved Great Britain, France, Spain, the Dutch Republic, Jamaica, Gibraltar and even India.”

And as to England suddenly finding peace, I personally think of that as 1948, when following two more world wars, they abandoned the two hundred year India mission. It’s not clear that seafaring England ever had much interest in the interior of any land they were fighting over – nor could they have imposed their will on a ‘colony’ that had fully reached the ability to sustain itself, with incalculable land available to produce that sustenance.

“Internal peace since the 17th century …”? Well, not really. There were the Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1745 when France tried to help the Scots depose the House of Hanover and put a Stuart King back on the British throne. Today, actually, is the 277th anniversary of the Battle of Culloden, the last major battle of the Forty-Five, in which Bonnie Prince Charlie was defeated by William “the Butcher” Duke of Cumberland.

But I see your point about the American Revolution being a reprise of the English Civil War, except that this time–thanks to the Atlantic Ocean–the colonists only had to renounce their allegiance to George III, not execute him as the Parliamentarians did to Charles I in 1649.

Also on the British/American Civil War theme is Alan Taylor’s 2010 book, “The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies”.

I have no expectations that the USA could pass “any” Constitutional Amendments in the foreseeable future. So as to writing a new constitution – fuhgettaboutit.

But I am curious how many other democratic” oriented countries have re-written their Constitutions and for what reasons.

And should we – discussed as a theoretical exercise.

Perhaps we are different because of our large number of States vs other countries with fewer “state” like regional governing entities.

Authoritarian states do it all the time.

Pete

The Australian Constitution has been amended eight times in 44 attempts. The first was soon after Federation in 1901, and the last successful effort was 1977. The Constitution can only be amended by referendum and it’s hard – it requires a majority of the votes in a majority of the states – and voting is compulsory.

Referendums always fail if one of the two major political parties supports the NO vote. The last attempt was 1999, with a movement to drop the British monarchy and to become a republic, however there was fatal in-fighting on the YES side over the form of the presidency – strong or weak powers, appointed by parliament or chosen by popular vote, etc.

Australian law (and its political space) are based on the Common Law and the legislation of the state and federal parliaments – there is no list of Ten Amendments (Bill of Rights), however human rights and individual freedoms are broadly enjoyed. We certainly don’t have the equivalent of the US Second or Fifth.

Our High Court (and the federal courts) play far less a role in the political sphere. Abortion rights are enjoyed in every state and territory, as is gay marriage. There is no practicable pathway for these to be challenged in the courts, so a lunatic-rogue-judge-in-Texas situation cannot arise. And no one in the judiciary or law enforcement is elected.

What always gets my goat is people’s belief in the Bill of Rights and how they are sacrosanct. Usually this starts Republicans off on a rant defending the 2nd Amendment, and I counter with the need to eliminate or modify the 1st. No, I’m not advocating a National Religion or the like, but I think one of the most damaging aspects from our form of government is how it’s evolved into a perpetual election cycle. Changing how elections happened would require Constitutional editing, but so would the First to restrict advertising. But if I were running things I’d blow up the whole damn thing and impose a Westminster Parliamentary type system. The US Constitution is too brittle.

It’s not the framework. It’s the political will. Here, obscene levels of wealth empower relatively few, in effect, to buy whatever government they want. It’s a process, not an end product, but key features of it are eroding checks and balances – competing centers of power – eroding faith in government and the law, and in education.

Parliamentary sovereignty (inadequate checks and balances), an unwritten constitution, and the lack of a bill of rights, which means Parliament can change them on a whim, are among the UK government’s greatest failings. The current Tory government is capitalizing on them as we speak. I would not adopt them here, even if given a proverbial blank slate.

“Parliamentary sovereignty (inadequate checks and balances), an unwritten constitution, and the lack of a bill of rights, which means Parliament can change them on a whim, are among the UK government’s greatest failings.”

I think you might be making the previous poster’s point for him or her very well – treating the Bill of Rights as sacrosanct. And I find the “checks and balances” argument very weak indeed – it mostly leads to gridlock, woeful time-wasting, and failed governance.

I live under a Westminster System (plus the robust Australian Constitution) and I vastly prefer it to the US republic model that operates at both the federal and state level. I particularly dislike the powers of governors, the powers of the courts, and of course the electoral process – from obscene money through to gerrymanders, and particularly first-past-the-post and winner-take-all voting.

It’s a myth to say the UK Conservatives (or any governing party) can change things “on a whim” – apart from the House of Lords and the High Court, the party has to face the electorate regularly. For example, it would be much harder in the UK (or indeed here in any Australian state) to turn back the clock on say same-sex marriage or abortion rights than it appears to be in the US.

No … from my outsider’s POV, the American political system looks an unholy mess that two centuries of band-aids and patching have made even worse.

The tragedy is that its deed systemic dysfunction plays perfectly for conservatives, and it has forever. Genuine reforms by a truly progressive party are extremely difficult, and by giving the “unrepresentative swill” in the Senate (to quote a colourful former Australian prime minister) such an absurd amount of power, it is nigh on impossible! Not for me I’m afraid.

Yes, power “coagulates” in places they were probably never intended to. SCOTUS basically gave itself the power of judicial review with Marbury v Madison, and that power has been abused by endorsing tyranny of the minority, in the form of gerrymandering and voter suppression, the 2nd Amendment “comma incident”, etc. There’s a lot of screwed up stuff at SCOTUS, and fixing any of it will be nigh on impossible because… brittle.

You live in a monarchy. It may be a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy, but it’s still a monarchy.

Are you advocating the US consider returning to a monarchy? Because seriously, piss off.

Nice straw man.

“Are you advocating the US consider returning to a monarchy? Because seriously, piss off.”

LOL settle down comrade … we live in a liberal democracy which is also a constitutional monarchy. I would actually prefer we had a ceremonial president (who spent their time cutting ribbons and handing out medals), but I don’t die on a hill over it, because it’s essentially inconsequential.

I like a parliamentary system because the greatest power is vested in the institution that is most representative – the people’s house – whereas the US system confers most power on three entities that are LESS representative: the Presidency, the Senate, and the Supreme Court.

It’s a very funny way to run a railroad!

Lol, thanks for the advice. You actually hail from a foreign country based on monarchy, and are lecturing that the US is a “Constitutional monarchy”? Seriously? So, you would have the US be run by the “people’s house”, i.e. the McCarthy and Jordan led GOP House? No thanks.

And, by the way, screw off with calling Rayne “comrade” and telling her to calm down. WTF is wrong with you? Same goes for “RodMunch” carping. You both are very much barking up the wrong trees. Don’t do that.

“You actually hail from a foreign country based on monarchy, and are lecturing that the US is a “Constitutional monarchy”? Seriously?”

LOL I think you need some remedial comprehension skills comrade! Nowhere have I said the US is a “constitutional monarchy” – not once, not ever. I haven’t even suggested it should be; I don’t presume to lecture.

I have expressed a strong preference for a Westminster Parliamentary system, with supreme power resting in a democratically and fairly elected house of representatives … harping on the issue of the monarchy is indeed a fairly blatant strawman … the position is purely ceremonial, as I suspect you well know.

All forums – just about – are international, and the Internet knows no national borders … I don’t live in a “foreign country” any more than you do … so I’m afraid your xenophobia is showing!

I might have butchered your description of Britain with your proselytizing to us in the US, sorry! But get lost with your “comrade” bullshit. The next time you pull that will be your last. Also, screw your “xenophobia” allegation. Get lost.

You can take your “comrade” and shove it. The reason the US democratic system looks messy to you is that an entire country — which began as 13 colonies and now consists of 50 states and some territories — has evolved this system, not an autocracy which deems occasionally to step aside and grant permission to its subjects.

What do the indigenous people of Australia feel about the federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy’s so-called “liberal democracy.” That’s a rhetorical question, spare yourself the energy.

P.S. You have three comments published as “Ian Williams” and now two as “Cargill.” Pick a username which contains at least 8 letters to comply with the site’s username policy and then stick with it.

Crikey, I missed the sockpuppeting.

“Pick a username which contains at least 8 letters to comply with the site’s username policy and then stick with it.”

I look forward to an explanation as to how “Rayne” (five letters) and “bmaz” (four letters) comply with this alleged policy.

It’s interesting that the word “comrade” can trigger certain people so much … it’s perfectly respectable, and has been used in trade union and Labor Party contexts for 150 years. What’s the issue, unless one is a virulent right-winger?

Go to hell. We have been here forever and are not your concern. You have been here a few times, and that includes your sock puppetry.

Thanks for the warm welcome to the forum … I love you too!

And I particularly admire you tolerance of points of view that might differ from your own.

[Welcome back to emptywheel. SECOND REQUEST: Please choose and use a unique username with a minimum of 8 letters and then stick with that new compliant username. We are moving to a new minimum standard to support community security. /~Rayne]

First, I suggest you familiarize yourself with this site by reading the About page. The contributors and moderators here as well as a small number of users with an established history of more than 1000 comments or more than a decade of comments here will be grandfathered — their identities are well established, particularly those of us who have the keys to the place and its liquor cabinet.

Second, policing of contributors and moderators by commenters — especially those with less than 10 comments documented and/or less than a month at this site — is not acceptable.

Third, fuck off with your gaslighting. You’re trolling, period. Keep up your bad faith participation here and I will help you find the exit.

I hadn’t heard of resentment about not being protected. Washington served in the British forces that fought the French and Indian War. The Stamp Tax was instituted by a |British Parliament that thought the Colonists should partially pay for their own defence.

Canadian eh ; so I see the Quebec Act as a major cause of the insurrection. A lot of people ( Franklin was one ) were horrified and terrified by the idea of giving Catholics civil rights, Indians land rights were also recognized in the act and were opposed by the land holding gentry who were greedy for more.

Strange bedfellows among the Thirteen, indeed: Maryland was established by Lord Baltimore as a proprietary colony to create a haven for English Catholics while other provinces explicitly proscribed the practice, e.g. Georgia’s founding document of 1732:

“…forever hereafter, there shall be a liberty of conscience allowed in the worship of God, to all persons inhabiting, or which shall inhabit or be resident within our said provinces and that all such persons, except papists, shall have a free exercise of their religion…”

“except papists”, lmao! Was discrimination against Jews just implied?

While “all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” was not at all true at the time they were written, those words have been very motivating throughout American history. Certainly, abolitionists found more support for their cause in the Declaration of Independence than in the bible. Sweeping ideals are valuable for motivating people to do better.

What I’ve read is that the Brits were tired of the costs of war and wanted the Colonists to pay for them, hence the tax. Additionally, they wanted to stop westward expansion, because that was the cause of the wars. George Washington was a surveyor. What they did was surveyed some un-charted land, then got a group of investors to buy it from the Indians. They didn’t pay much attention to title, so the tribes they bought the land from were usually not the ones who actually had control over it. Because of westward expansion, the natives were being pushed out of their territories and into other tribes’ territories, so there were overlapping claims. When the Colonists settled the land, the tribes that controlled the land often tried to turf them out — ie started wars, which the Colonists expected the Brits to help them fight.

Which wars did the Brits want the colonies to pay for? Surely not the ones against Boney? Manifest Destiny wasn’t for another 50 years or so.

The French and Indian War and subsequent protection.

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Like many of you, I grew up reading what was printed about America, its Founders–legends all–and their noble motives and ideals. The facts that built the legend are not so clear, and often contradictory, but the legend prevails. The legend is aspirational for us and others. That’s not a bad thing.

We needn’t have originated as a Constitutional government codified in a single document but for better or worse, we did. It is the majority.

But these aren’t all created the same, and interestingly enough those countries having a non-codified Constitution are in a vast minority, but exist as some of our closest, oft-cited examples: Canada, UK, Sweden, Israel.

It’s not quite fair then to compare how UK or Canada or Sweden lightly views their Constitution relative to US. Our closer peer comparisons may be better to use Iran or Venezuela, countries which severely adhere to their codified Constitutions, most especially during strife or “Constitutional crises.”

Also part of US romantic regard is also like centered in romantic facade of revolutionary success. We love stories if the little guy winning over the big one, and so our entrenched regard for Revolutionary War will be tough to dislodge.

We shouldn’t underestimate the effect of geography in bringing about the American Revolution. Even at the time, there were those who questioned how long European powers could expect to exercise control over their colonies on the other side of the Atlantic, given that communications to and from colonial administrators were measured in weeks and months. These was especially true of New France, which was cut off from the home country for about half the year because of the navigational hazards of ice in the St. Lawrence River.

In the fall of 1758, in the midst of the Seven Years’ War, the Marquis de Montcalm ordered his aide-de-camp, Louis Antoine de Bougainville, to take ship back to France and impress upon the authorities the need for reinforcements and supplies for Canada. Bougainville received a cool reception at court and later recorded that some French officials did not consider Canada to be a worthwhile investment in the long term. “[W]hen once Canada was well established, it would pass through many phases”, these officials told him, and “would it not be natural that kingdoms and republics should be formed there and should separate from France?” Bougainville agreed and predicted in 1759, “It is true that in the course of time those vast territories may be divided into Kingdoms and republics, and the same thing is true of New England.” From “Canada: The War of the Conquest” by Guy Frégault, trans. Margaret M. Cameron, 1969

Great article and interesting discusson, including the fireworks. Two things I reflect on about our nation, is that we have feet of clay but at least the potential (and so far, with some demonstratable success) to achieve what we find aspirational in the flawed documents that we pretend to revere. Perhaps we have reached some cul-de-sac, but I’m optimisitc. I keep this same attitude about myself – forgiving my past shortcomings with penance being the will to look at the worst [Hardy, De Profundis: “. . . if a way to the Better there be, it exacts a full look at the Worst”] not to condemn but to learn how better to be.

Great article and interesting discusson, including the fireworks.

Two things I reflect on about our nation, is that we have feet of clay but at least the potential (and so far, with some demonstratable success) to achieve what we find aspirational in the flawed documents that we pretend to revere. Perhaps we have reached some cul-de-sac, but I’m optimisitc. I keep this same attitude about myself – forgiving my past shortcomings with penance being the will to look at the worst [Hardy, De Profundis: “. . . if a way to the Better there be, it exacts a full look at the Worst”] not to condemn, but to learn how better to be.

The other is that, however we came, cobbled, to be a nation, we were at least unified enough geographically and ideologically to have the resources and the will to counter Hitler. I don’t know if in the present or future that we can maintain that unity or that we can avoid the corruption that often attends great power, but we certainly have a chance. More so when we see ourselves in the individual struggle for living among others who are not less nor more than we, but also in our participation to the extent possible as citizens striving to correct our worst tendencies as a nation, and encourage the best.

Ed writes: “If the Constitution were actually about individual human rights…”

Each of the 13 sovereign states had already written constitutions that defined for their state what “self-evident” Rights men “had been endowed with by their Creator.” That project had been completed a decade earlier. Now, there was a desperate need for a Constitution that would enable the 13 former colonies to work together in a “more perfect union”, but no need to deal with the settled problem of human Rights. Therefore, the Constitutional Convention focused on how the new Federal government would function. This drafting process had consumed more than three months and everyone was exhausted. However, because the proposed Constitution gave large powers to a federal government, many recognized a need for a Bill of Rights to protect people from the power of the new Federal government. They settled for a promise that the first Congress would propose a Bill of Rights in the form of amendments to the Constitution. In the new Congress, Madison took the lead in this process, using the rights already enshrined in many state constitutions and proposed during state ratifying conventions as the basis for the amendments he proposed.

The “Federal” Bill of Rights initially only limited the power of the Federal government. The Civil War Amendments created a need expand the protection of the Federal Bill of Rights against the power of the individual States, which was done by the 14th amendment.

Ed wrote: “As to slavery, there are three provisions that directly or indirectly support its continuation: the Three-Fifths Clause, a provision barring the Federal Government from ending the international slave trade until 1808, and the Fugitive Slave Clause. Each of these cemented the power of the slave states.”

Some therefore conclude that the Constitution was a “pro-slavery” document. However, by 1787, the country was already divided into a pro-slavery South and an anti-slavery North. VT had banned slavery when it formed its government in 1777. MA and PA had abolished slavery, the former because its court ruled that the phrase “all men are created equal” in its state constitution meant slavery was illegal. The other Northern states had begun or would soon begin a more gradual emancipation process. The Constitution doesn’t explicitly mention slavery because the Northern states would never have ratified a Constitution that explicitly mentioned slavery or a right to own “property in man”. For this reason and others, Fredrick Douglass argued the Constitution was an anti-slavery document. The Constitution was a typical political compromise with something to please everyone, and vague language concerning controversial subjects. Slavery had recently been banned in the Northwest Territory under the Articles of Confederation. The new US Congress would immediately confirm this, and IIRC fail to pass Jefferson’s proposed ban on slavery in all territories by a single vote due to the absence of one northern Representative.

Ed writes: “The prohibition on ending the slave trade before 1808 enabled slavers to rebuild their holdings by importation after losses in the Revolutionary War.”

However, records of slave voyages show only 20,000 new slaves were imported before 1804 and 68,000 in the last four years before 1808 (as cotton began booming?). Most of the half million slaves added between 1790 and 1810 were born here and a negligible fraction replaced those lost during the Revolution.

The Constitution required each state to recognize the “Privileges and Immunities” granted to citizens of other states. Consistent with the provision, fugitives from one state were subject to extradition and the “Fugitive Slave Clause” allowed slave holders from one state to travel to free states and recover their “property” – without referring to that property “slaves”. Northerners wouldn’t be required to assist in this process until the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (one of the causes of the Civil War).

Ed wrote: “Nor was the Revolution fought to advance a broad principle of equality. Roosevelt says that the statement that all men are created equal is a reference to the fictional state of nature assumed to exist in the beginning.”

As I wrote earlier, Roosevelt is a law school professor advocating for the “non-greatness” of our Founders, not a historian fairly weighing the evidence. The full discussion of “all men are created equal” says:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Yes, all men were created equal with the right to life, liberty and pursuit of happiness (which meant civil virtue to Jefferson) in our “natural” state, but the Founders were NOT trying to establish a broad principle of equality – they were attempting to secure THEIR RIGHTS by breaking their ties with the King and instituting a new government. They were already at war with the King’s soldiers. Their goal was to attract as many colonists and foreign countries as possible to their Cause. The Founding generation provided us the freedom and a government that would later let us debate exactly which unalienable Rights we want our government to secure and what it means to be “created equal” (equality of opportunity? equality of outcome?) in a world where evolution has endowed everyone with the innate ability to instantly be alert to those who don’t belong to our “tribe” and a mind with limited capable of overruling those instincts