The Fifteenth Amendment

After the 14th Amendment and the Reconstruction Act of 1867 were adopted the Freedmen in the former slave states had the vote. That left all the Black men in the Union and Border States and Tennessee, and that eventually was seen to be untenable. The Democrats, then the right-wing party, made universal Black suffrage an issue in the election of 1868. In The Second Founding, Eric Foner says this campaign “… witnessed some of the most overt appeals to racism in American political history.” P. 97. Grant won, but the popular vote was close, and Democrats made gains across the Union. That gave impetus to passage of an amendment to ensure the vote to all Black men.

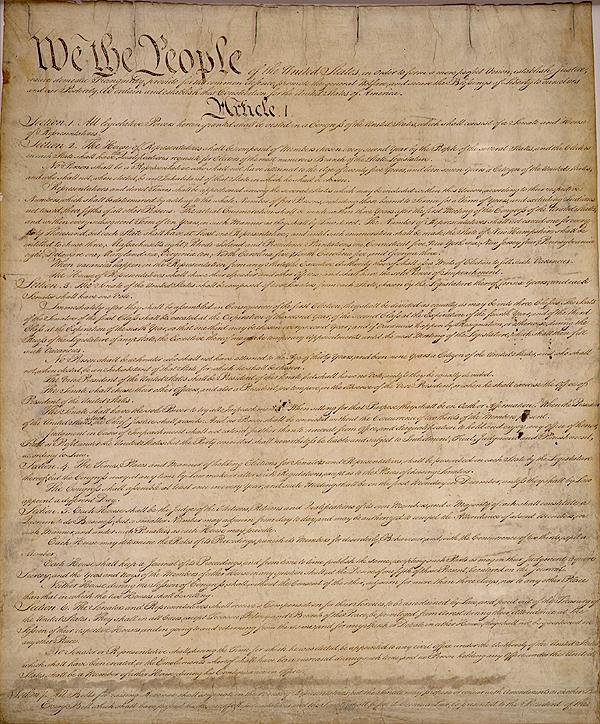

Several amendments were introduced. The main choice was whether to support universal suffrage or only for Black men. The Radical Republicans wanted a bill setting national standards for voting, a position consonant with Art. 1 § 4 of the Constitution.

But here the true level of US bigotry revealed itself. Several Union states made it clear they wouldn’t support suffrage for Germans and/or Irish Catholics (and as one of the latter, I’d say we’re pretty harmless). In the West, prejudice against Chinese immigrants was a powerful force, evoking racist comments akin to those directed at Black people. As time expired, we got the Fifteenth Amendment in its most limited form:

1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Section 2 authorizes Congress to make laws enforcing Section 1.

Section 1 is not a positive grant of suffrage to Black people. Instead, it authorizes the states to control suffrage as they see fit as long as they don’t use race as a condition. Thus it authorized Ohio to deny suffrage to German immigrants, and Rhode Island to grant suffrage only to Irish Catholic property owners; and it enabled the states to use non-racial laws to exclude Black men from the polls.

The Republicans worried that Northern states wouldn’t ratify a positive version, granting suffrage to all adult males, let alone a broader version, barring discrimination on the basis of, for example, religion. There was no question of enfranchising women or Native Americans. The final draft of the bill in each house included the right to hold office, but that was eliminated in conference, and the House version of a positive enfranchisement was dropped in favor of the Senate’s negative version.

Foner points out that legislators knew that the negative version could be gamed by the states, but assumed, or perhaps hoped, that the 14th Amendment would make that poisonous to the slave states, because discriminatory requirements would affect White people too. But that turned out to be a false hope, thanks in large part to the efforts of the Supreme Court. Also, it turns out that rich white Southerners weren’t opposed to blocking poor whites from the ballot box, or shielding them from the laws with other techniques.

The first few years after the Civil War saw the creation of a number of White vigilante groups, including the Ku Klux Klan. These groups wreaked terror on Black people across the former Confederacy, murdering and raping, pillaging and burning. The slave states did nothing to stop this hideous violence, and they did nothing for decades, leaving their Black populations to die, leave, or suffer in silence.

In the early 1870s Congress began consideration of laws to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments. Three bills, the Enforcement Acts, gave the federal government the power to punish violence against Black people, using federal courts and marshals. But they were inadequate to force the slave states to protect their Black citizens. Eventually Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which was a comprehensive effort to protect Black people from all kinds of private violence intended to deny Black people the rights guaranteed by the Reconstruction Amendments.

In the debates over all these laws, a substantial number of federal legislators called these laws violations of the principles of federalism. As we will see, the Supreme Court agreed, and struck down the new laws. Eventually because of the intransigence of the Court, the 13th Amendment was ignored, the 14th Amendment was gutted, and the 15th Amendment was barely useful.

Discussion

1. Foner integrates into his text excerpts from the debates in Congress over the Amendments, and from newspaper articles, giving a flavor of the rhetoric and feelings of the speakers and perhaps those of the elites. Here’s a nice example:

“Tell me nothing of a constitution,” declared Joseph H. Rainey, a black congressman from South Carolina whose father, a successful barber, had purchased the family’s freedom in the 1840s, “which fails to shelter beneath its rightful power the people of a country.” By the people who needed protection, Rainey made clear, he meant not only blacks but also white Republicans in the South. If the Constitution, he added, was unable to “afford security to life, liberty, and property,” it should be “set aside.” P. 119. Fn omitted.

The other side was equally direct and eloquent:

In the debate over the Ku Klux Klan Act, Carl Schurz, representing Missouri in the Senate, said that preserving intact the tradition of local self-government was even more important than “the high duty to protect the citizens of the republic in their rights.” Lyman Trumbull complained that the Ku Klux Klan Act would “change the character of the government.” P. 120.

These anecdotes make this book a real pleasure to read. They remind us that our ancestors were thoughtful and forthright, or even bombastic, whether or not we agree with their sentiments today. I do not think the same of the former members of the Supreme Court, whose opinions are very difficult to read, and reek of unwillingness to deal with the Reconstruction Amendments and the facts of the cases they decided.

2. These quotes illustrate the issues around federalism. Both of the books in this series claim that the Reconstruction Amendments changed the nature of the US governing structure, by giving the federal government the power to protect the Constitutionally guaranteed rights of its citizens from private parties and from the states themselves. As we know, this hasn’t exactly worked out in practice. Even today and even in the supposedly less-racist cities and states, police and private citizens violate the civil rights of citizens, use all sorts of tricks to strip the power of minority voters, and treat citizens differently. SCOTUS is fine with that, as we saw in the ridiculous advisory opinion in 303 Creative.

We need a discussion of the purposes of federalism in this country, and we need to discuss publicly what it means to be an American citizen as opposed to a citizen of Mississippi or Minnesota. Why is it that our fundamental rights arise from citizenship in Mississippi or Minnesota, instead of from our national document, the Constitution? I’m pretty sure most uses of federalism are to discriminate against or punish people the benighted legislature doesn’t like.

3. Constitutional amendments and laws don’t change people’s minds. The Civil War didn’t really change any minds. Is it possible that elites, including supreme courts can’t get out of their own privileged pasts?

As soon as you started this thread, I went to my library and checked out the book The Second Founding. Thanks for the tip.

Another interesting nerd read is the Dredd Scott decision. At that time each justice wrote separately so the case runs over 200 pages but you get the gist without that intense a study. In school (50 years ago) they tended to pass over the case only noting it’s odious comment that a black man has no rights that a court need respect. In fact however, the majority sets out the clearest original intent argument you might ever encounter. The details of how the US constitution protected slavery are carefully laid out, and the court’s ruling against Scott’s claim that he became a free man when his owner took him to the free state of Illinois follows. In doing so, the court undermined 30 years worth of compromise and set the stage for war.

By all means also read “Reconstruction” by Foner if you haven’t already. A very tough read at times, since he discusses many instances of how brutal and cruel things were for Black people in those years after the Civil War, and how many in the U.S. government were just fine with a practical return to slavery if it meant that economic interests would be served and the nation would be “reunited.”

I;ve never read Dred Scott, but your description agrees with a point made by Kermit Roosevelt in The Nation That Never Was. He says that the founders Constitution did in fact support slavery, and that the decision in Dred Scott is in line with that intent.

To the Founders, the rights of property in enslaved people were the same property rights secured by the 5th Amendment, and this argument was persuasive in the face of more general ideas about the equality of all men laid out in the Declaration.

The decision is reviled today, but it’s not worse than the arguments in other SCOTUS cases denying rights, deleting rights, and ignoring our basic principles, cases like Lochner, Korematsu, Dobbs and many others.

SCOTUS has always been the last line of defense for bigots of all stripes and the filthy rich. They’re limiting our future, if not consigning us to disaster.

Your final statement is very powerful.

“… They’re limiting our future, if not consigning us to disaster.”

Thank you for adding this very thought-worthy post.

The older I get, the clearer that becomes to me. The whole book of Romans (NT) talks about this.

I think it did. Just not enough to transform society’s fucked up head space. I read somewhere recently (don’t recall where) Lincoln addressed this very question in his own soul searching: (my paraphrase) that being whether he should fight further to change minds, or accept relentless southern racism towards blacks despite the war. The article said he decided on the later.

It was not clear whether Lincoln came to this conclusion from carefully reasoned wisdom, or fatigue. I had never heard this before, found it to be serious food for thought because it was Lincoln. Particularly because, again as I’m getting older (68) and look back at “battles” I’ve participated in over last 20+ years have yielded incremental improvement at best. And it seems way to slow… way too slow. Biggest case in point is humanity’s planet wide inability (or lack of will) for decades to deal with climate, which is becoming more and more apparent to more and more people every year. Major parts of our physical (eg. EARTH) reality are not waiting for humanity to get their shit together.

I guess that’s one way to put it. Not very satisfying however. Sometimes understanding is the booby prize, I think.

You only need to look at the civil rights struggles of the last 50-70 years to see progress has been made — it takes generations, though, and backsliding is possible when deterrence isn’t addressed from the bottom at local level to the top of the federal government. For example, in my lifetime these rights have changed in the public’s perception:

We could finally intermarry across the country, BIPOC and white. (Loving v. Virginia)

We had the ability to control our reproductive health, both in preventing conception and through abortion. (Griswold v. Connecticut, Roe v. Wade)

We could finally have a relationship and marry a person who identifies as the same gender as ourselves. (Lawrence v. Texas, Obergefell v. Hodges)

My adult kids and most of their cohort don’t accept a present or future in which these rights are denied.

Our problem has been a failure to build into our culture a system which beats back encroachment on these rights, including a system by which we analyze threats to these rights and construct proactive responses, one which factors in fatigue.

Those unenumerated rights I used as an example have been under attack before the SCOTUS decisions which acknowledged them, and since then — the Dobbs decision being the worst in its reversal of reproductive rights on a state-by-state basis — could and should have been predicted, but apparently it takes losing some rights before the threat is taken seriously.

Perhaps it was fatigue which allowed the backsliding. Perhaps the rights were taken for granted because who in the 1970s-1990s would have predicted a SCOTUS so willing to ignore stare decisis? We raised a generation of adults who no longer saw the war for our rights continued because they never experienced the loss. But now we should be asking ourselves about the next successive moves the fascistic right-wing will take; we know our right to privacy is one of their targets.

And maybe it has and will take some losses before the public grasps the threat to our fundamental right to life posed by the constant externalization of costs by corporations which have set the climate emergency in motion. What successive moves will the fascistic right-wing take to continue their vampiric existence? Have we learned anything at all from the attacks this SCOTUS has made on our rights already to plan for their next assaults? It won’t take as much to change minds about the effort needed if their bodies are suffocating from wildfire smoke.

Agree.

Perhaps. :) And perhaps it was/is practicing… as in every day of their lives, really really bad habits. Things that hurt others, but preserve their right to perpetuate that. I call that cultural. If someone is born/raised in a family steeped in bigoted Bible thumping hate, these attitudes are their learnedrights before they ever find out they had constitutionally enumerated ones that are a little better. :)

This is a problem. :)

I’m all for codifying rights into law. But there are a lot of other things that have been happening simultaneously in the society and the world while this progress has progressed, which these rights have had little or no affect in slowing down. Climate just happens to be the most obvious one right here, right now.

And we are woefully unprepared to deal with it. That we are squabbling about rights in the midst of very self evident existential threat that we are not close to even beginning a full fledged response to, is a testament to that.

I think you’ve said before that the backsliding has been stupendously enabled by today’s immense inequality of wealth, combined with a post-Powell memo willingness of those with the most wealth to use it to erode democracy and our system of government, in order to promote their own power and wealth. The dynamic isn’t unique, but the tools available have improved remarkably.

It took 95 years from the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The statute worked wonderfully and statistics show the increased percentage of African Americans registered to vote in the 11 Old Confederate slave states that levied war against the United States.

Then came chief justice James Crow roberts junior and his four sidekicks to decide Shelby County v Holder. In order to declare parts of the Votnig Rights Act unconstitutional he had to Nullify the Fifteenth Amendment just as the “railroad lawyers nominated by Gilded Age REpublican president” did in Plessy v Ferguaon in 1896.

As a young lawyer in Reagan’s nonJusticeeJustice Department roberts junior urged Reagan to veto the 1982 extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 which passed the House 389 to 24 and the Senate 85 to 8.

roberts junior really, really, really does not like African Americans voting.

For a country (USA) that boasts of itself as being exceptional we do seem to have an exceptionally hard time getting basic common sense freedoms for ALL “enshrined”.

BTW Ed – I’m German Catholic and so also (pretty much) harmless – though the Catholic part has petty much lapsed due to the church’s hypocrisy.

Thank you for this post — I learned a lot!

[Welcome to emptywheel. Please choose and use a unique username with a minimum of 8 letters. We are moving to a new minimum standard to support community security. Thanks. /~Rayne]

We seem to have forgotten the phrase “White Anglo-Saxon Protestant” or WASP. We can be glad it’s an irrelevant category today (…is it?) but we shouldn’t forget our history.