Ben Wittes has a summary of last Wednesday’s “Going Dark” hearings. He engages in a really amusing straw man — comparing a hypothetically perfectly secure Internet with ungoverned Somalia.

Consider the conceptual question first. Would it be a good idea to have a world-wide communications infrastructure that is, as Bruce Schneier has aptly put it, secure from all attackers? That is, if we could snap our fingers and make all device-to-device communications perfectly secure against interception from the Chinese, from hackers, from the FSB but also from the FBI even wielding lawful process, would that be desireable? Or, in the alternative, do we want to create an internet as secure as possible from everyone except government investigators exercising their legal authorities with the understanding that other countries may do the same?

Conceptually speaking, I am with Comey on this question—and the matter does not seem to me an especially close call. The belief in principle in creating a giant world-wide network on which surveillance is technically impossible is really an argument for the creation of the world’s largest ungoverned space. I understand why techno-anarchists find this idea so appealing. I can’t imagine for moment, however, why anyone else would.

Consider the comparable argument in physical space: the creation of a city in which authorities are entirely dependent on citizen reporting of bad conduct but have no direct visibility onto what happens on the streets and no ability to conduct search warrants (even with court orders) or to patrol parks or street corners. Would you want to live in that city? The idea that ungoverned spaces really suck is not controversial when you’re talking about Yemen or Somalia. I see nothing more attractive about the creation of a worldwide architecture in which it is technically impossible to intercept and read ISIS communications with followers or to follow child predators into chatrooms where they go after kids.

This gets the issue precisely backwards, attributing all possible security and governance to policing alone, and none to prevention, and as a result envisioning chaos in a possibility that would, in fact, have less or at least different kinds chaos. Wittes simply dismisses the benefits of a perfectly secure Internet (which is what all the pro-backdoor witnesses at the hearings did too, ignoring, for example, the effect that encrypting phones would have on a really terrible iPhone theft problem). But Wittes’ straw man isn’t central to his argument, just a tell about his biases.

Wittes, like Comey, also suggests the technologists are wrong when they say back doors will be bad.

There is some reason, in my view, to suspect that the picture may not be quite as stark as the computer scientists make it seem. After all, the big tech companies increase the complexity of their software products all the time, and they generally regard the increased attack surface of the software they create as a result as a mitigatable problem. Similarly, there are lots of high-value intelligence targets that we have to secure and would have big security implications if we could not do so successfully. And when it really counts, that task is not hopeless. Google and Apple and Facebook are not without tools in the cybersecurity department.

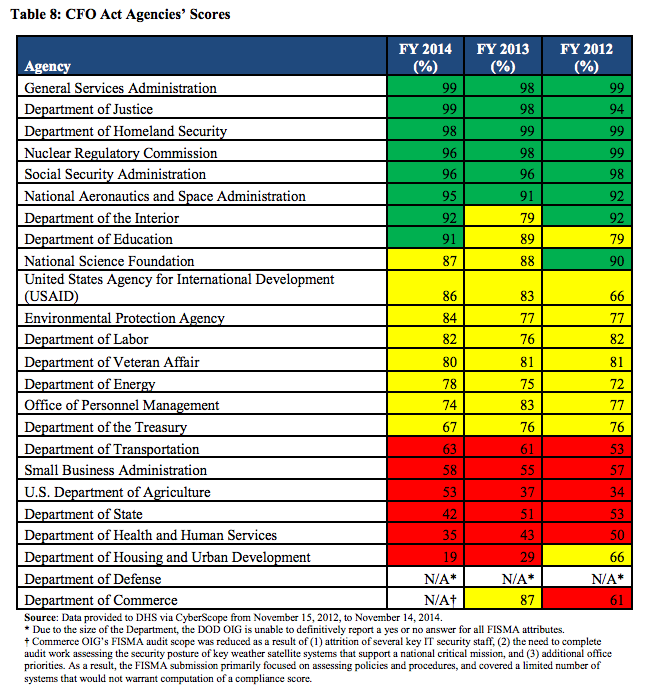

Wittes appears unaware that the US has failed miserably at securing its high value intelligence targets, so it’s not a great counterexample.

But I’m primarily interested in Wittes’ fondness for an idea floated by Sheldon Whitehouse: that the government force providers to better weigh the risk of security by ensuring it bears liability if the cops can’t access communications.

Another, perhaps softer, possibility is to rely on the possibility of civil liability to incentivize companies to focus on these issues. At the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing this past week, the always interesting Senator Sheldon Whitehouse posed a question to Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates about which I’ve been thinking as well: “A girl goes missing. A neighbor reports that they saw her being taken into a van out in front of the house. The police are called. They come to the home. The parents are frantic. The girl’s phone is still at home.” The phone, however, is encrypted:

WHITEHOUSE: It strikes me that one of the balances that we have in these circumstances where a company may wish to privatize value by saying, “Gosh, we’re secure now. We got a really good product. You’re going to love it.” That’s to their benefit. But for the family of the girl that disappeared in the van, that’s a pretty big cost. And when we see corporations privatizing value and socializing cost so that other people have to bear the cost, one of the ways that we get back to that and try to put some balance into it, is through the civil courts, through a liability system.

If you’re a polluter and you’re dumping poisonous waste into the water rather than treating it properly, somebody downstream can bring an action and can get damages for the harm that they sustain, can get an order telling you to knock it off. I’d be interested in whether or not the Department of Justice has done any analysis as to what role the civil-liability system might be playing now to support these companies in drawing the correct balance, or if they’ve immunized themselves from the cost entirely and are enjoying the benefits. I think in terms of our determination as to what, if anything, we should do, knowing where the Department of Justice believes the civil liability system leaves us might be a helpful piece of information. So I don’t know if you’ve undertaken that, but if you have, I’d appreciate it if you’d share that with us, and if you’d consider doing it, I think that might be helpful to us.

YATES: We would be glad to look at that. It’s not something that we have done any kind of detailed analysis. We’ve been working hard on trying to figure out what the solution on the front end might be so that we’re not in a situation where there could potentially be corporate liability or the inability to be able to access the device.

WHITEHOUSE: But in terms of just looking at this situation, does it not appear that it looks like a situation where value is being privatized and costs are being socialized onto the rest of us?

YATES: That’s certainly one way to look at it. And perhaps the companies have done greater analysis on that than we have. But it’s certainly something we can look at.

I’m not sure what that lawsuit looks like under current law. I, like the Justice Department, have not done the analysis, and I would be very interested in hearing from anyone who has. Whitehouse, however, seems to me to be onto something here. Might a victim of an ISIS attack domestically committed by someone who communicated and plotted using communications architecture specifically designed to be immune, and specifically marketed as immune, from law enforcement surveillance have a claim against the provider who offered that service even after the director of the FBI began specifically warning that ISIS was using such infrastructure to plan attacks? To the extent such companies have no liability in such circumstances, is that the distribution of risk that we as a society want? And might the possibility of civil liability, either under current law or under some hypothetical change to current law, incentivize the development of secure systems that are nonetheless subject to surveillance under limited circumstances?

Why don’t we make the corporations liable, these two security hawks ask!!!

This, at a time when the cybersecurity solution on the table (CISA and other cybersecurity bills) gives corporations overly broad immunity from liability.

Think about that.

While Wittes hasn’t said whether he supports the immunity bills on the table, Paul Rosenzweig and other Lawfare writers are loudly in favor of expansive immunity. And Sheldon Whitehouse, whose idea this is, has been talking about building in immunity for corporations in cybersecurity plans since 2010.

I get there is a need for limited protection for corporations that help the Federal government spy (especially if they’re required to help), which is what liability is always about. I also get that every time we award it, it keeps getting bigger, and years later we discover that immunity covers fairly audacious spying far beyond the ostensible intent of the bill. Though CISA doesn’t even hide that this data will be used for purposes far beyond cybersecurity.

Far, far more importantly, however, one of the problems with the cyber bills on the table is by awarding this immunity, they’re creating a risk calculation for corporations to be sloppy. Sure, there will still be reputational damage every time a corporation exposes its customers’ data to hackers. But we’ve seen in the financial sector — where at least bank regulators require certain levels of hygiene and reporting — bank immunity tied to these reporting requirements appears to have made it impossible to prosecute egregious bank crime.

The banks have learned (and they will be key participants in CISA) that they can obtain impunity by sharing promiscuously (or even not so promiscuously) with the government.

And unlike those bank reporting laws, CISA doesn’t require hygiene. It doesn’t require that corporations deploy basic defenses before obtaining their immunity for information sharing.

If liability is such a great idea, then why aren’t these men pushing the use of liability as a tool to improve our cyberdefenses, rather than (on Whitehouse’s part, at least) calling for the opposite?

Indeed, if this is about appropriately balancing risk, there is no way you can use liability to get corporations to weigh the value of back doors for law enforcement, without at the same time ensuring all corporations also bear full liability for any insecurity in their system, because otherwise corporations won’t be weighing the two sides.

Using liability as a tool might be a clever idea. But using it only for law enforcement back doors does nothing to identify the appropriate balance.

![[photo: K2D2vaca via Flickr]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Chrysler_K2D2vaca-Flickr-300x218.jpg)