Riley Meets the Dragnet: Does “Inspection” amount to “Rummaging”?

It’s clear today’s decision in Riley v. California will be important in the criminal justice context. What’s less clear is its impact for national security dragnets.

To answer the question, though, we should remember that question really amounts to several. Does it affect the existing phone dragnet, which aspires to collect the phone records of every person in the US? Does it affect the government’s process of collecting massive amounts of data from which to cull an individual’s data to make up a “fingerprint” that can be used for targeting and other purposes? Will it affect the program the government plans to implement under USA Freedumber, in which the telecoms perform connection-based chaining for the NSA, and then return Call Detail Records as results? Does it affect Section 702? I think the answer may be different for each of these, though I think John Roberts’ language is dangerous for all of this.

In any case, Roberts wants it to be unclear. This footnote, especially, claims this opinion does not implicate cases — governed by the Third Party doctrine — where the collection of data is not considered a search.

1Because the United States and California agree that these cases involve searches incident to arrest, these cases do not implicate the question whether the collection or inspection of aggregated digital information amounts to a search under other circumstances.

Orin Kerr reads this as addressing the mosaic theory directly — which holds that a Fourth Amendment review must consider the entirety of the government collection — (and he is the expert, after all). Though I’m not impressed with his claim that the analogue language Roberts uses directly addresses the mosaic theory; Kerr seems to be arguing that because Roberts finds another argument unwieldy, he must be addressing the theory that Kerr himself finds unwieldy. Moreover, in addition to this section, which Kerr says supports the Mosaic theory,

An Internet search and browsing history, for example, can be found on an Internet-enabled phone and could reveal an individual’s private interests or concerns—perhaps a search for certain symptoms of disease, coupled with frequent visits to WebMD. Data on a cell phone can also reveal where a person has been. Historic location information is a stand-ard feature on many smart phones and can reconstruct someone’s specific movements down to the minute, not only around town but also within a particular building. See United States v. Jones, 565 U. S. ___, ___ (2012) (SOTOMAYOR, J., concurring) (slip op., at 3) (“GPS monitoring generates a precise, comprehensive record of a person’s public movements that reflects a wealth of detail about her familial, political, professional, religious, and sexual associations.”).

I think the paragraph below it also supports the Mosaic theory — particularly its reference to a “revealing montage of the user’s life.”

Mobile application software on a cell phone, or “apps,” offer a range of tools for managing detailed information about all aspects of a person’s life. There are apps for Democratic Party news and Republican Party news; apps for alcohol, drug, and gambling addictions; apps for sharing prayer requests; apps for tracking pregnancy symptoms; apps for planning your budget; apps for every conceivable hobby or pastime; apps for improving your romantic life. There are popular apps for buying or selling just about anything, and the records of such transactions may be accessible on the phone indefinitely. There are over a million apps available in each of the two major app stores; the phrase “there’s an app for that” is now part of the popular lexicon. The average smart phone user has installed 33 apps, which together can form a revealing montage of the user’s life.

I’d argue that the opinion as a whole endorses the notion that you need to assess the totality of the surveillance in question. But then the footnote adopts the awkward phrase, “collection or inspection of aggregated digital information,” to suggest there may be some arrangement under which the conduct of such analysis might not constitute a search requiring a higher standard. (And all that still leaves the likely possibility that the government would scream “special need” and get an exception to get the data anyway; as they surely will do to justify ongoing border searches of computers.)

Of crucial importance, then, Roberts seems to be saying that it might be okay to conduct mosaic analysis, depending on where you get the data and/or whether you actually obtain or instead simply inspect the data.

That’s crucial, of course, because the government is, as we speak, replacing a phone dragnet in which it collects all the data from everyone and analyzes it (or rather, claims to only access only a minuscule portion of it, claiming to do so only through phone-based contacts) with one where it will go to “inspect” the data at telecoms.

So Roberts seems to have left himself an out (or included language designed to placate even Democrats like Stephen Breyer, to say nothing of Clarence Thomas, to achieve unanimity) that happens to line up nicely with where the phone dragnet, at least, is heading.

All that said, Robert’s caveat may not be broad enough to cover the new-and-improved phone dragnet as the government plans to implement it. After all, the “connection” based analysis the government intends to do may only survive via some kind of argument that letting telecoms serve as surrogate spooks makes this kosher under the Fourth Amendment. Because we have every reason to expect that the NSA intends to — at least — tie multiple online and telecom identities together to chain on all of them, and use cell location to track who you meet. And they may well (likely, if not now, then eventually) intend to use things like calendars and address books that Roberts argues makes cell phones not cell phones, but minicomputers that serve as “cameras,video players, rolodexes, calendars, tape recorders, libraries, diaries, albums, televisions, maps, or newspapers.” Every single one of those minicomputer functions is a potential “connection” based chain.

So while the new-and-improved phone dragnet may fall under Roberts’ “inspect” language, it involves far more yoking of the many functions of cell phones that Roberts finds to be problematic.

Then there’s this passage, that Roberts used to deny the government the ability to “just” get call logs.

We also reject the United States’ final suggestion that officers should always be able to search a phone’s call log,as they did in Wurie’s case. The Government relies on Smith v. Maryland, 442 U. S. 735 (1979), which held that no warrant was required to use a pen register at telephone company premises to identify numbers dialed by a particular caller. The Court in that case, however, concluded that the use of a pen register was not a “search” at all under the Fourth Amendment. See id., at 745–746. There is no dispute here that the officers engaged in a search of Wurie’s cell phone. Moreover, call logs typically contain more than just phone numbers; they include any identifying information that an individual might add, such as the label “my house” in Wurie’s case. [my emphasis]

The first part of this passage makes a similar kind of distinction as you see in that footnote (and may support my suspicion that Roberts is trying to carve out space for the new-and-improved phone dragnet). Using a pen register at a telecom is not a search, because it doesn’t involve seizing the phone itself.

But the second part of this passage — which distinguishes between pen registers and call logs — seems to be the most direct assault on the Third Party doctrine in this opinion, because it suggests that data that has been enhanced by a user — phone numbers that are not just phone numbers — may not fall squarely under Smith v. Maryland.

And that’s important because the government intends to get far more data than phone numbers while at the telecoms under the new-and-improved phone dragnet. It surely at least aspires to get logs just like the one Roberts says the cops couldn’t get from Wurie.

Think, too, of how this should limit all the US person data the government collects overseas that the government then aggregates to make fingerprints, claiming incidentally collected data does not require any legal process. That data is seized not from telecoms but rather stolen off cables — does that count as public collection or seizure?

Perhaps the language that presents the most sweeping danger to the dragnet, however, is the line that both Kerr and I like best from the opinion.

Alternatively, the Government proposes that law enforcement agencies “develop protocols to address” concerns raised by cloud computing. Reply Brief in No. 13–212, pp. 14–15. Probably a good idea, but the Founders did not fight a revolution to gain the right to government agency protocols.

Admittedly, Roberts is addressing a specific issue, the government’s proposal of how to protect personal data stored on a cloud that might be accessed from a phone (as if the government gives a shit about such things!).

But the underlying principle is critical. For every single dragnet program the government conducts at NSA, it dismisses obvious Fourth Amendment concerns by pointing to minimization procedures.

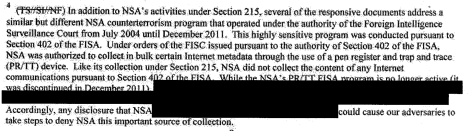

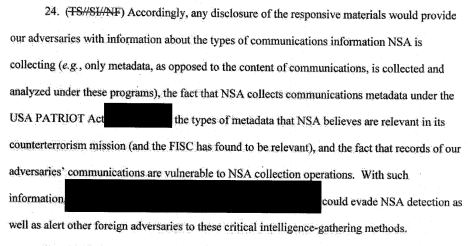

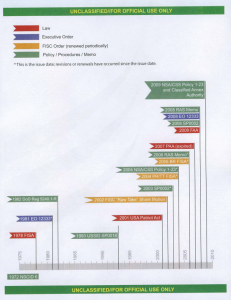

The FISC allowed the government to conduct the phone dragnet because it had purportedly strict minimization procedures (which the government ignored); it allowed the government to conduct an Internet dragnet for the same reason; John Bates permitted the government to address domestic content collection he deemed a violation of the Fourth Amendment with new minimization procedures; and the 2008 FISCR opinion approving the Protect America Act (which FISCR and the government say covers FAA as well) relied on targeting and minimization procedures to judge it compliant with the Fourth Amendment. FISC is also increasingly using minimization procedures to deem other Section 215 collections compliant with the law, though we know almost nothing about what they’re collecting (though it’s almost certain they involve Mosaic collection).

Everything, everything, ev-er-y-thing the NSA does these days complies with the Fourth Amendment only under the theory that minimization procedures — “government agency protocols” — provide adequate protection under the Fourth Amendment.

It will take a lot of work, in cases in which the government will likely deny anyone has standing, with SCOTUS’ help, to make this argument. But John Roberts said today that the government agency protocols that have become the sole guardians of the Fourth Amendment are not actually what our Founders were thinking of.

Ultimately, though, this passage may be Roberts’ strongest condemnation — whether he means it or not — of the current dragnet.

Our cases have recognized that the Fourth Amendment was the founding generation’s response to the reviled “general warrants” and “writs of assistance” of the colonial era, which allowed British officers to rummage through homes in an unrestrained search for evidence of criminal activity. Opposition to such searches was in fact one of the driving forces behind the Revolution itself.

Roberts elsewhere says that cell searches are more intrusive than home searches. And by stealing and aggregating that data that originates on our cell phones, the government is indeed rummaging in unrestrained searches for evidence of criminal activity or dissidence. Roberts likely doesn’t imagine this language applies to the NSA (in part because NSA has downplayed what it is doing). But if anyone ever gets an opportunity to demonstrate all that NSA does to the Court, it will have to invent some hoops to deem it anything but digital rummaging.

I strongly suspect Roberts believes the government “inspects” rather than “rummages,” and so believes his opinion won’t affect the government’s ability to rummage, at least at the telecoms. But a great deal of the language in this opinion raises big problems with the dragnets.