The Fishing Expedition into WikiLeaks

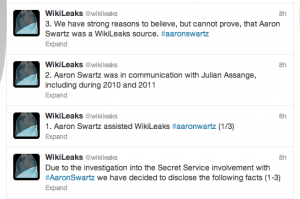

If, as WikiLeaks claims, Aaron Swartz:

If, as WikiLeaks claims, Aaron Swartz:

- Assisted WikiLeaks

- Communicated with Julian Assange in 2010 and 2011

- May have contributed material to WikiLeaks

Then it strongly indicates the US government used the grand jury investigation into Aaron’s JSTOR downloads as a premise to investigate WikiLeaks. And they did so, apparently, only after the main grand jury investigation into WikiLeaks had stalled.

(See this Verge article on the ways these tweets appear to violate WikiLeaks’ promises of confidentiality.)

As I noted in this post, when Aaron’s lawyer requested discovery last June, he wanted material that had been subpoenaed or otherwise collected but not turned over in discovery–material that does not have an obvious tie to Aaron’s relatively simple alleged crime of downloading journal articles from JSTOR.

These paragraphs request information relating to grand jury subpoenas. Paragraph 1 requested that the government provide “[a]ny and all grand jury subpoenas – and any and all information resulting from their service – seeking information from third parties including but not limited to Twitter. MIT, JSTOR, Internet Archive that would constitute a communication from or to Aaron Swartz or any computer associated with him.” Paragraph 4 requested “[a]ny and all SCA applications, orders or subpoenas to MIT, JSTOR, Twitter, Google, Amazon, Internet Archive or any other entity seeking information regarding Aaron Swartz, any account associated with Swartz, or any information regarding communications to and from Swartz and any and all information resulting from their service.” Paragraph 20 requested “[a]ny and all paper, documents, materials, information and data of any kind received by the Government as a result of the service of any grand jury subpoena on any person or entity relating to this investigation.”

Swartz requests this information because some grand jury subpoenas used in this case contained directives to the recipients which Swartz contends were in conflict with Rule 6(e)(2)(A), see United States v. Kramer, 864 F.2d 99, 101 (11th Cir. 1988), and others sought certification of the produced documents so that they could be offered into evidence under Fed. R. Evid. 803(6), 901. Swartz requires the requested materials to determine whether there is a further basis for moving to exclude evidence under the Fourth Amendment (even though the SCA has no independent suppression remedy).

[snip]

Moreover, defendant believes that the items would not have been subpoenaed by the experienced and respected senior prosecutor, nor would evidentiary certifications have been requested, were the subpoenaed items not material to either the prosecution or the defense. Defendant’s viewing of any undisclosed subpoenaed materials would not be burdensome, and disclosure of the subpoenas would not intrude upon the government’s work product privilege, as the subpoenas were served on third parties, thus waiving any confidentiality or privilege protections. [my emphasis]

Given that this material (I’m particularly interested in the material Amazon returned to the grand jury, though also the Twitter and Google material, which after all, the main WikiLeaks grand jury requested for public WikiLeaks figures) had not been turned over to Aaron’s defense almost a full year after he was indicted, it’s fairly clear it did not pertain to (or certainly was not necessary to prove) the charges against him, which related to JSTOR.

Yet prosecutor Stephen Heymann had used a grand jury he was using to investigate that JSTOR download–a grand jury that appears not to have gotten started in earnest until the main WikiLeaks grand jury had stalled–to collect information that appears directly relevant to the WikiLeaks grand jury. And he collected it in a form such that could be directly entered as evidence into that WikiLeaks grand jury.

Let me clear about two things. First, I think this is perfectly within the range of what grand juries do. If the government suspected–and they appear to have–that Aaron’s JSTOR downloads were part of a larger effort, then it’s not surprising they investigated broadly to determine whether it was. That’s part of the significant power of grand juries–they can expand in secret to fish for other crimes. As judge Judith Dein said when rejecting Aaron’s effort to see what the government had gotten from these subpoenas, citing US v. Dionisio, “A grand jury’s investigation is not fully carried out until every available clue has been run down and all witnesses examined in every proper way to find if a crime has been committed.”

But even after this fishing expedition (and I hope to show in a later post just how broad it appears to have been), Heymann apparently came up with no evidence that Aaron had broken any laws related to whatever he did with and for WikiLeaks (again, assuming WikiLeaks’ assertions are correct). After investigating for over a year, Heymann added no charges pertaining to WikiLeaks.

He just ratcheted up the charges related to JSTOR.

It appears the government tried–and failed–to establish a criminal connection between Aaron and WikiLeaks. And when they failed to do that, they increased their hardline stance on the JSTOR charges.