EO 12333 Sharing Will Likely Expose Security Researchers Even More Via Back Door Searches

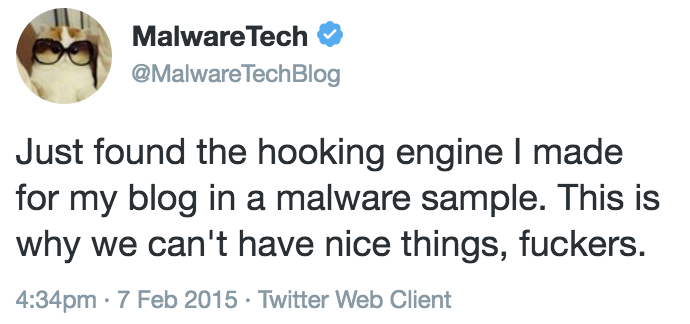

At Motherboard, I have piece arguing that the best way to try to understand the Marcus Hutchins (MalwareTech) case is not from what we see in his indictment for authoring code that appears in a piece of Kronos malware sold in 2015. Instead, we should consider why Hutchins would look different to the FBI in 2016 (when the government didn’t arrest him while he was in Las Vegas) and 2017 (when they did). In 2016, he’d look like a bit player in a minor dark market purchase made in 2015. In 2017, he might look like a guy who had his finger on the WannaCry malware, but also whose purported product, Kronos, had been incorporated into a really powerful bot he had long closely tracked, Kelihos.

Hutchins’ name shows up in chats obtained in an investigation in some other district. Just one alias for Hutchins—his widely known “MalwareTech”—is mentioned in the indictment. None of the four or more aliases Hutchins may have used, mostly while still a minor, was included in the indictment, as those aliases likely would have been if the case in chief relied upon evidence under that alias.

Presuming the government’s collection of both sets of chat logs predates the WannaCry outbreak, if the FBI searched on Hutchins after he sinkholed the ransomware, both sets of chat logs would come up. Indeed, so would any other chat logs or—for example—email communications collected under Section 702 from providers like Yahoo, Google, and Apple, business records from which are included in the discovery to be provided in Hutchins’ case in FBI’s possession at that time. Indeed, such data would come up even if they showed no evidence of guilt on the part of Hutchins, but which might interest or alarm FBI investigators.

There is another known investigation that might elicit real concern (or interest) at the FBI if Hutchins’s name showed up in its internal Google search: the investigation into the Kelihos botnet, for which the government obtained a Rule 41 hacking warrant in Alaska on April 10 and announced the indictment of Russian Pyotr Levashov in Connecticut on April 21. Eleven lines describing the investigation in the affidavit for the hacking warrant remain redacted. In both its announcement of his arrest and in the complaint against Levashov for operating the Kelihos botnet, the government describes the Kelihos botnet loading “a malicious Word document designed to infect the computer with the Kronos banking Trojan.”

Hutchins has tracked the Kelihos botnet for years—he even attributes his job to that effort. Before his arrest and for a period that extended after Levashov’s arrest, Hutchins ran a Kelihos tracker, though it has gone dead since his arrest. In other words, the government believes a later version of the malware it accuses Hutchins of having a hand in writing was, up until the months before the WannaCry outbreak—being deployed by a botnet he closely tracked.

There are a number of other online discussions Hutchins might have participated in that would come up in an FBI search (again, even putting aside more dated activity from when he was a teenager). Notably, the attack on two separate fundraisers for his legal defense by credit card fraudsters suggests that corner of the criminal world doesn’t want Hutchins to mount an aggressive defense.

All of which is to say that the FBI is seeing a picture of Hutchins that is vastly different than the public is seeing from either just the indictment and known facts about Kronos, or even open source investigations into Hutchins’ past activity online.

To understand why Hutchins was arrested in 2017 but not in 2016, I argue, you need to understand what a back door search conducted on him in May would look like in connection with the WannaCry malware, not what the Kronos malware looks like as a risk to the US (it’s not a big one).

I also note, however, that in addition to the things FBI admitted they searched on during their FBI Google searches — Customs and Border Protection data, foreign intelligence reports, FBI’s own case files, and FISA data (both traditional and 702) — there’s something new in that pot: data collected under EO 12333 shared under January’s new sharing procedures.

That data is likely to expose a lot more security researchers for behavior that looks incriminating. That’s because FBI is almost certainly prioritizing asking NSA to share criminal hacker forums — where security researchers may interact with people they’re trying to defend against in ways that can look suspicious if reviewed out of context. That’s true, first of all, because many of those forums (and other dark web sites) are overseas, and so are more accessible to NSA collection. The crimes those forums facilitate definitely impact US victims. But criminal hacking data — as distinct from hacking data tied to a group that the government has argued is sponsored by a nation-state — is also less available via Section 702 collection, which as far as we know still limits cybersecurity collection to the Foreign Government certificate.

If I were the FBI I would have used the new rules to obtain vast swaths of data sitting in NSA’s coffers to facilitate cybersecurity investigations.

So among the NSA-collected data we should expect FBI newly obtained in raw form in January is that from criminal hacking forums. Indeed, new dark web collection may have facilitated FBI’s rather impressive global bust of several dark web marketing sites this year. (The sharing also means FBI will no longer have to go the same lengths to launder such data it obtains targeting kiddie porn, which it appears to have done in the PlayPen case.)

As I think is clear, such data will be invaluable for FBI as it continues to fight online crime that operates internationally. But because back door searches happen out of context, at a time when the FBI may not really understand what it is looking at, it also risks exposing security researchers in new ways to FBI’s scrutiny.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)