If One Judge Gives FISA Review, and Another Judge Gives FISA Review, All Hell Will Break Loose!

There have been a couple of developments on the government’s effort to continue its practice of shielding its dragnet from adversarial legal review behind the screen of FISA.

First, the 7th Circuit appears to want to punt on the question of whether or not Adel Daoud’s lawyer should be able to review the FISA materials used against him.

It claims (incorrectly, I suspect) it may not have the authority to review Sharon Coleman’s decision to give Daoud review.

A preliminary review of the short record indicates that the order appealed from may not be an appealable order.

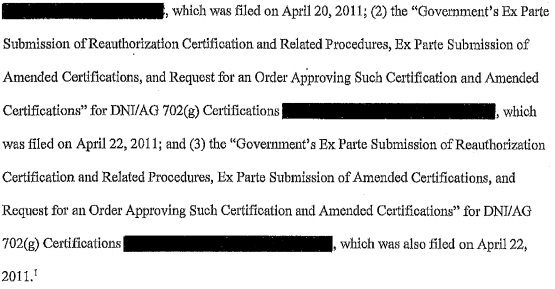

Section 3731 of Title 18, United States Code, permits the United States to appeal certain rulings in a criminal case. The district court’s order of January 29, 2014, compelling disclosure of Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act application materials to defense counsel having the necessary clearance, does not appear to fit within the statute’s list of orders that the government can appeal.

Meanwhile, in Oregon, the government has submitted its response to Mohamed Osman Mohamud’s discovery request for details of why the government didn’t tell him it had used FISA Section 702 to identify him before his trial. (h/t to Mike Scarcella on both documents)

I’ll come back to the substance of that response, as I think it shows the strategy the government will attempt to use to dig out of its discovery obligation hole in Section 702 cases.

But I wanted to point out footnote 19:

A district court order requiring the disclosure of FISA materials is a final order for purposes of appeal. See 50 U.S.C. § 1806(h). In the unlikely event that the Court concludes that disclosure of the classified FAA-related information that defendant requests may be required, given the significant national security consequences that would result from such disclosure, the government would expect to pursue an appeal. Accordingly, the government respectfully requests that the Court indicate its intent to do so before issuing any order, or that any such order be issued in such a manner that the United States has sufficient notice to file an appeal prior to any actual disclosure.

The government is pointing to what will surely be the core of the debate in the 7th Circuit, whether 50 USC 1806(h)‘s mention of Appeals Court review of disclosure decisions trumps criminal code.

But it’s also revealing something else: with its suggestion that a judge might rule in favor of discovery and start handing over FISA warrant applications willy nilly, and therefore it should get warning before any judge rules against it, it betrays a concern that if judges actual so rule (even assuming they can appeal), it will harm their case.

The government seems to be admitting that one of the only things preventing judges from granting such review is the long history DOJ can point to when no judge has granted such review (which is a line they always use when defendants try to get such review).

It’s the taboo, the unquestioning deference courts have granted every time the Attorney General has claimed such review would harm national security without actually explaining why, that prevents defendants from getting review.

Not any real risk to national security.

And DOJ seems anxious to maintain the power of that taboo at all costs.

One more bit of ironic arrogance in this footnote: the government is suggesting it should get advance review on a ruling about the consequences they might suffer for failing to give a defendant advance review.

Update: I just noticed that Mohamud’s lawyer gave notice of the Daoud ruling and indicated that like Daoud’s lawyer, he also has TS/SCI clearance.

Update: Whoo boy. DOJ is panicking, I think. They’ve suggested that if either of two statutes they cite don’t give the 7th Circuit jurisdiction they should issue a writ of mandamus.

Finally, if the two statutory bases for appellate jurisd iction set forth above were not available, this Court would still have jurisdiction to issue a writ of mandamus to revers e the district court’s order pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1651.