This post took a great deal of time, both in this go-around, and over the years to read all of these opinions carefully. Please consider donating to support this work.

It often surprises people when I tell them this, but in general, I’ve got a much better opinion of the FISA Court than most other civil libertarians. I do so because I’ve actually read the opinions. And while there are some real stinkers in the bunch, I recognize that the court has long been a source of some control over the executive branch, at times even applying more stringent standards than criminal courts.

But Rosemary Collyer’s April 26, 2017 opinion approving new Section 702 certificates undermines all the trust and regard I have for the FISA Court. It embodies everything that can go wrong with the court — which is all the more inexcusable given efforts to improve the court’s transparency and process since the Snowden leaks. I don’t think she understood what she was ruling on. And when faced with evidence of years of abuse (and the government’s attempt to hide it), she did little to rein in or even ensure accountability for those abuses.

This post is divided into three sections:

- My analysis of the aspects of the opinion that deal with the upstream surveillance

- Describing upstream searches

- Refusing to count the impact

- Treating the problem as exclusively about MCTs, not SCTs

- Defining key terms

- Failing to appoint (much less consider) appointing an amicus

- Approving back door upstream searches

- Imposing no consequences

- A description of all the documents I Con the Record released — and more importantly, the more important ones it did not release (if you’re in the mood for weeds, start there)

- A timeline showing how NSA tried to hide these violations from FISC

Opinion

The Collyer opinion deals with a range of issues: an expansion of data sharing with the National Counterterrorism Center, the resolution of past abuses, and the rote approval of 702 certificates for form and content.

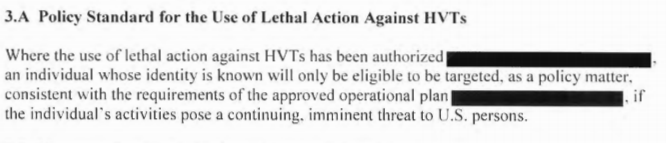

But the big news from the opinion is that the NSA discovered it had been violating the terms of upstream FISA collection set in 2011 (after violating the terms of upstream FISA set in 2007-2008, terms which were set after Stellar Wind violated FISA since 2002). After five months of trying and failing to find an adequate solution to fix the problem, NSA proposed and Collyer approved new rules for upstream collection. The collection conducted under FISA Section 702 is narrower than it had been because NSA can no longer do “about” searches (which are basically searching for some signature in the “content” of a communication). But it is broader — and still potentially problematic — because NSA now has permission to do the back door searches of upstream collected data that they had, in reality, been doing all along.

My analysis here will focus on the issue of upstream collection, because that is what matters going forward, though I will note problems with the opinion addressing other topics to the extent they support my larger point.

Describing upstream searches

Upstream collection under Section 702 is the collection of communications identified by packet sniffing for a selector at telecommunication switches. As an example, if the NSA wants to collect the communications of someone who doesn’t use Google or Yahoo, they will search for the email address as it passes across circuits the government has access to (overseas, under EO 12333) or that a US telecommunications company runs (domestically, under 702; note many of the data centers at which this occurs have recently changed hands). Stellar Wind — the illegal warrantless wiretap program done under Bush — was upstream surveillance. The period in 2007 when the government tried to replace Stellar Wind under traditional FISA was upstream surveillance. And the Protect America Act and FISA Amendments Act have always included upstream surveillance as part of the mix, even as they moved more (roughly 90% according to a 2011 estimate) of the collection to US-based providers.

The thing is, there’s no reason to believe NSA has ever fully explained how upstream surveillance works to the FISC, not even in this most recent go-around (and it’s now clear that they always lied about how they were using and processing a form of upstream collection to get Internet metadata from 2004 to 2011). Perhaps ironically, the most detailed discussions of the technology behind it likely occurred in 2004 and 2010 in advance of opinions authorizing collection of metadata, not content, but NSA was definitely not fully forthcoming in those discussions about how it processed upstream data.

In 2011, the NSA explained (for the first time), that it was not just collecting communications by searching for a selector in metadata, but it was also collecting communications that included a selector as content. One reason they might do this is to obtain forwarded emails involving a target, but there are clearly other reasons. As a result of looking for selectors as content, NSA got a lot of entirely domestic communications, both in what NSA called multiple communication transactions (“MCTs,” basically emails and other things sent in bundles) and in single communication transactions (SCTs) that NSA didn’t identify as domestic, perhaps because they used Tor or a VPN or were routed overseas for some other reason. The presiding judge in 2011, John Bates, ruled that the bundled stuff violated the Fourth Amendment and imposed new protections — including the requirement NSA segregate that data — for some of the MCTs. Bizarrely, he did not rule the domestic SCTs problematic, on the logic that those entirely domestic communications might have foreign intelligence value.

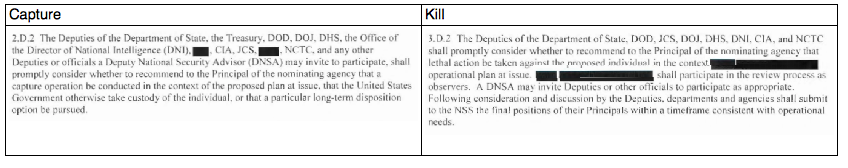

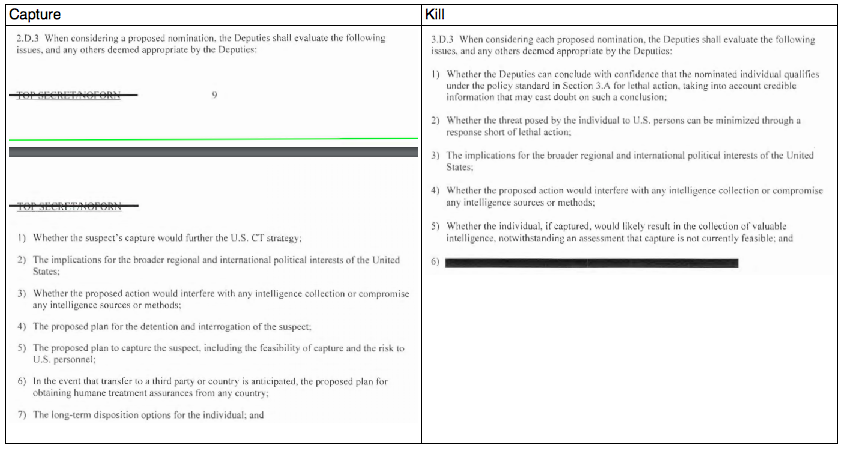

In the same order, John Bates for the first time let CIA and NSA do something FBI had already been doing: taking US person selectors (like an email address) and searching through already collected content to see what communications they were involved in (this was partly a response to the 2009 Nidal Hasan attack, which FBI didn’t prevent in part because they were never able to pull up all of Hasan’s communications with Anwar al-Awlaki at once). Following Ron Wyden’s lead, these searches on US person content are often called “back door searches” for the way they let the government read Americans’ communications without a warrant. Because of the newly disclosed risk that upstream collection could pick up domestic communications, however, when Bates approved back door searches in 2011, he explicitly prohibited the back door searching of data collected via upstream searches. He prohibited this for all of it — MCTs (many of which were segregated from general repositories) and SCTs (none of which were segregated).

As I’ve noted, as early as 2013, NSA knew it was conducting “many” back door searches of upstream data. The reasons why it was doing so were stupid: in part, because to avoid upstream searches analysts had to exclude upstream repositories from the search query (basically by writing “NOT upstream” in a Boolean query), which also required them realizing they were searching on a US person selector. For whatever reason, though, no one got alarmed by reports this was going on — not NSA’s overseers, not FISC (which reportedly got notices of these searches), and not Congress (which got notices of them in Semiannual reports, which is how I knew they were going on). So the problem continued; I noted that this was a persistent problem back in August, when NSA and DOJ were still hiding the extent of the problems from FISC.

It became clear the problem was far worse than known, however, when NSA started looking into how it dealt with 704 surveillance. Section 704 is the authority the NSA uses to spy on Americans who are overseas. It basically amounts to getting a FISC order to use EO 12333 spying on an American. An IG Report completed in January 2016 generally found 704 surveillance to be a clusterfuck; as part of that, though, the NSA discovered that there were a whole bunch of 704 backdoor searches that weren’t following the rules, in part because they were collecting US person communications for periods outside of the period when the FISC had authorized surveillance (for 705(b) communication, which is the spying on Americans who are simply traveling overseas, this might mean NSA used EO 12333 to collect on an American when they were in the US). Then NSA’s Compliance people (OCO) did some more checking and found still worse problems.

And then the government — the same government that boasted about properly disclosing this to FISC — tried to bury it, basically not even telling FISC about how bad the problem was until days before Collyer was set to approve new certificates in October 2016. Once they did disclose it, Judge Collyer gave NSA first one and then another extension for them to figure out what went wrong. After 5 months of figuring, they were still having problems nailing it down or even finding where the data and searches had occurred. So, finally, facing a choice of ending “about” collection (only under 702 — they can still accomplish the very same thing under EO 12333) or ending searches of upstream data, they chose the former option, which Collyer approved with almost no accountability for all the problems she saw in the process.

Refusing to count the impact

I believe that (at least given what has been made public) Collyer didn’t really understand the issue placed before her. One thing she does is just operate on assumptions about the impact of certain practices. For example, she uses the 2011 number for the volume of total 702 collection accomplished using upstream collection to claim that it is “a small percentage of NSA’s overall collection of Internet communications under Section 702.” That’s likely still true, but she provides no basis for the claim, and it’s possible changes in communication — such as the increased popularity of Twitter — would change the mix significantly.

Similarly, she assumes that MCTs that involve “a non-U.S. person outside the United States” will be “for that reason [] less likely to contain a large volume of information about U.S. person or domestic communications.” She makes a similar assumption (this time in her treatment of the new NCTC raw take) about 702 data being less intrusive than individual orders targeted at someone in the US, “which often involve targets who are United States persons and typically are directed at persons in the United States.” In both of these, she repeats an assumption John Bates made in 2011 when he first approved back door searches using the same logic — that it was okay to provide raw access to this data, collected without a warrant, because it wouldn’t be as impactful as the data collected with an individual order. And the assumption may be true in both cases. But in an age of increasingly global data flows, that remains unproven. Certainly, with ISIS recruiters located in Syria attempting to recruit Americans, that would not be true at all.

Collyer makes the same move when she makes a critical move in the opinion, when she asserts that “NSA’s elimination of ‘abouts’ collection should reduce the number of communications acquired under Section 702 to which a U.S. person or a person in the United States is a party.” Again, that’s probably true, but it is not clear she has investigated all the possible ways Americans will still be sucked up (which she acknowledges will happen).

And she does this even as NSA was providing her unreliable numbers.

The government later reported that it had inadvertently misstated the percentage of NSA’s overall upstream Internet collection during the relevant period that could have been affected by this [misidentification of MCTs] error (the government first reported the percentage as roughly 1.3% when it was roughly 3.7%.

Collyer’s reliance on assumptions rather than real numbers is all the more unforgivable given one of the changes she approved with this order: basically, permitting the the agencies to conduct otherwise impermissible searches to be able to count how many Americans get sucked up under 702. In other words, she was told, at length, that Congress wants this number (the government’s application even cites the April 22, 2106 letter from members of the House Judiciary Committee asking for such a number). Moreover, she was told that NSA had already started trying to do such counts.

The government has since [that is, sometime between September 26 and April 26] orally notified the Court that, in order to respond to these requests and in reliance on this provision of its minimization procedures, NSA has made some otherwise-noncompliant queries of data acquired under Section 702 by means other than upstream Internet collection.

And yet she doesn’t then demand real numbers herself (again, in 2011, Bates got NSA to do at least a limited count of the impact of the upstream problems).

Treating the problem as exclusively about MCTs, not SCTs

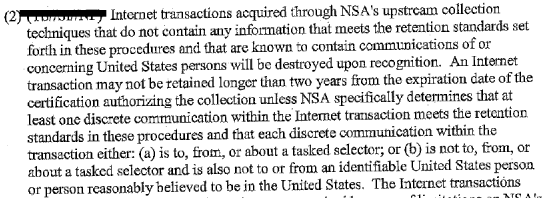

But the bigger problem with Collyer’s discussion is that she treats all of the problem of upstream collection as being about MCTs, not SCTs. This is true in general — the term single communication transaction or SCT doesn’t appear at all in the opinion. But she also, at times, makes claims about MCTs that are more generally true for SCTs. For example, she cites one aspect of NSA’s minimization procedures that applies generally to all upstream collection, but describes it as only applying to MCTs.

A shorter retention period was also put into place, whereby an MCT of any type could not be retained longer than two years after the expiration of the certificate pursuant to which it was acquired, unless applicable criteria were met. And, of greatest relevance to the present discussion, those procedures categorically prohibited NSA analysts from using known U.S.-person identifiers to query the results of upstream Internet collection. (17-18)

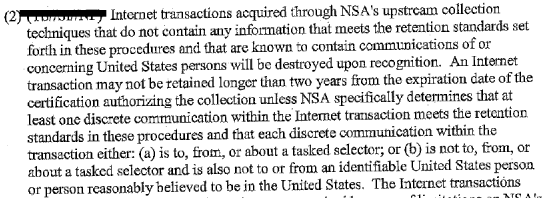

Here’s the section of the minimization procedures that imposed the two year retention deadline, which is an entirely different section than that describing the special handling for MCTs.

Similarly, Collyer cites a passage from the 2015 Hogan opinion stating that upstream “is more likely than other forms of section 702 collection to contain information of or concerning United States person with no foreign intelligence value” (see page 17). But that passage cites to a passage of the 2011 Bates opinion that includes SCTs in its discussion, as in this sentence.

In addition to these MCTs, NSA likely acquires tens of thousands more wholly domestic communications every year, given that NSA’s upstream collection devices will acquire a wholly domestic “about” SCT if it is routed internationally. (33)

Collyer’s failure to address SCTs is problematic because — as I explain here — the bulk of the searches implicating US persons almost certainly searched SCTs, not MCTs. That’s true for two reasons. First, because (at least according to Bates’ 2011 guesstimate) NSA collects (or collected) far more entirely domestic communications via SCTs than via MCTs. Here’s how Bates made that calculation in 2011 (see footnote 32).

NSA ultimately did not provide the Court with an estimate of the number of wholly domestic “about” SCTs that may be acquired through its upstream collection. Instead, NSA has concluded that “the probability of encountering wholly domestic communications in transactions that feature only a single, discrete communication should be smaller — and certainly no greater — than potentially encountering wholly domestic communications within MCTs.” Sept. 13 Submission at 2.

The Court understands this to mean that the percentage of wholly domestic communications within the universe of SCTs acquired through NSA’s upstream collection should not exceed the percentage of MCTs within its statistical sample. Since NSA found 10 MCTs with wholly domestic communications within the 5,081 MCTs reviewed, the relevant percentage is .197% (10/5,081). Aug. 16 Submission at 5.

NSA’s manual review found that approximately 90% of the 50,440 transactions in the same were SCTs. Id. at 3. Ninety percent of the approximately 13.25 million total Internet transactions acquired by NSA through its upstream collection during the six-month period, works out to be approximately 11,925,000 transactions. Those 11,925,000 transactions would constitute the universe of SCTs acquired during the six-month period, and .197% of that universe would be approximately 23,000 wholly domestic SCTs. Thus, NSA may be acquiring as many as 46,000 wholly domestic “about” SCTs each year, in addition to the 2,000-10,000 MCTs referenced above.

Assuming some of this happens because people use VPNs or Tor, then the amount of entirely domestic communications collected via upstream would presumably have increased significantly in the interim period. Indeed, the redaction in this passage likely hides a reference to technologies that obscure location.

If so, it would seem to acknowledge NSA collects entirely domestic communications using upstream that obscure their location.

The other reason the problem is likely worse with SCTs is because — as I noted above — no SCTs were segregated from NSA’s general repositories, whereas some MCTs were supposed to be (and in any case, in 2011 the SCTs constituted by far the bulk of upstream collection).

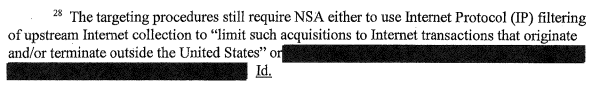

Now, Collyer’s failure to deal with SCTs may or may not matter for her ultimate analysis that upstream collection without “about” collection solves the problem. Collyer limits the collection of abouts by limiting upstream collection to communications where “the active user is the target of acquisition.” She describes “active user” as “the user of a communication service to or from whom the MCT is in transit when it is acquired (e.g., the user of an e-mail account [half line redacted].” If upstream signatures are limited to emails and texts, that would seem to fix the problem. But upstream wouldn’t necessarily be limited to emails and texts — upstream collection would be particularly valuable for searching on other kinds of selectors, such as an encryption key, and there may be more than one person who would use those other kinds of selectors. And when Collyer says, “NSA may target for acquisition a particular ‘selector,’ which is typically a facility such as a telephone number or e-mail address,” I worry she’s unaware or simply not ensuring that NSA won’t use upstream to search for non-typical signatures that might function as abouts even if they’re not “content.” The problem is treating this as a content/metadata distinction, when “metadata” (however far down in the packet you go) could include stuff that functions like an about selector.

Defining key terms terms

Collyer did define “active user,” however inadequately. But there are a number of other terms that go undefined in this opinion. By far the funniest is when Collyer notes that the government’s March 30 submission promises to sequester upstream data that is stored in “institutionally managed repositories.” In a footnote, she notes they don’t define the term. Then she pretty much drops the issue. This comes in an opinion that shows FBI data has been wandering around in repositories it didn’t belong and indicating that NSA can’t identify where all its 704 data is. Yet she’s told there is some other kind of repository and she doesn’t make a point to figure out what the hell that means.

Later, in a discussion of other violations, Collyer introduces the term “data object,” which she always uses in quotation marks, without explaining what that is.

Failing to appoint (or even consider) amicus

In any case, this opinion makes clear that what should have happened, years ago, is a careful discussion of how packet sniffing works, and where a packet collected by a backbone provider stops being metadata and starts being content, and all the kinds of data NSA might want to and does collect via domestic packet sniffing. (They collect far more under EO 12333.) As mentioned, some of that discussion may have taken place in advance of the 2004 and 2010 opinions approving upstream collection of Internet metadata (though, again, I’m now convinced NSA was always lying about what it would take to process that data). But there’s no evidence the discussion has ever happened when discussing the collection of upstream content. As a result, judges are still using made up terms like MCTs, rather than adopting terms that have real technical meaning.

For that reason, it’s particularly troubling Collyer didn’t use — didn’t even consider using, according to the available documentation — an amicus. As Collyer herself notes, upstream surveillance “has represented more than its share of the challenges in implementing Section 702” (and, I’d add, Internet metadata collection).

At a minimum, when NSA was pitching fixes to this, she should have stopped and said, “this sounds like a significant decision” and brought in amicus Amy Jeffress or Marc Zwillinger to help her think through whether this solution really fixes the problem. Even better, she should have brought in a technical expert who, at a minimum, could have explained to her that SCTs pose as big a problem as MCTs; Steve Bellovin — one of the authors of this paper that explores the content versus metadata issue in depth — was already cleared to serve as the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board’s technical expert, so presumably could easily have been brought into consult here.

That didn’t happen. And while the decision whether or not to appoint an amicus is at the court’s discretion, Collyer is obligated to explain why she didn’t choose to appoint one for anything that presents a significant interpretation of the law.

A court established under subsection (a) or (b), consistent with the requirement of subsection (c) and any other statutory requirement that the court act expeditiously or within a stated time–

(A) shall appoint an individual who has been designated under paragraph (1) to serve as amicus curiae to assist such court in the consideration of any application for an order or review that, in the opinion of the court, presents a novel or significant interpretation of the law, unless the court issues a finding that such appointment is not appropriate;

For what it’s worth, my guess is that Collyer didn’t want to extend the 2015 certificates (as it was, she didn’t extend them as long as NSA had asked in January), so figured there wasn’t time. There are other aspects of this opinion that make it seem like she just gave up at the end. But that still doesn’t excuse her from explaining why she didn’t appoint one.

Instead, she wrote a shitty opinion that doesn’t appear to fully understand the issue and that defers, once again, the issue of what counts as content in a packet.

Approving back door upstream searches

Collyer’s failure to appoint an amicus is most problematic when it comes to her decision to reverse John Bates’ restriction on doing back door searches on upstream data.

To restate what I suggested above, by all appearances, NSA largely blew off the Bates’ restriction. Indeed, Collyer notes in passing that, “In practice, however, no analysts received the requisite training to work with the segregated MCTs.” Given the persistent problems with back door searches on upstream data, it’s hard to believe NSA took that restriction seriously at all (particularly since it refused to consider a technical fix to the requirement to exclude upstream from searches). So Collyer’s approval of back door searches of upstream data is, for all intents and purposes, the sanctioning of behavior that NSA refused to stop, even when told to.

And the way in which she sanctions it is very problematic.

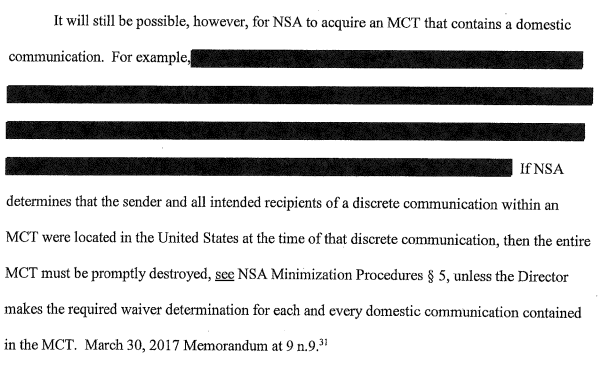

First, in spite of her judgment that ending about searches would fix the problems in (as she described it) MCT collection, she nevertheless laid out a scenario (see page 27) where an MCT would acquire an entirely domestic communication.

Having laid out that there will still be some entirely domestic comms in the collection, Collyer then goes on to say this:

The Court agrees that the removal of “abouts” communications eliminates the types of communications presenting the Court the greatest level of constitutional and statutory concern. As discussed above, the October 3, 2011 Memorandum Opinion (finding the then-proposed NSA Minimization Procedures deficient in their handling of some types of MCTs) noted that MCTs in which the target was the active user, and therefore a party to all of the discrete communications within the MCT, did not present the same statutory and constitutional concerns as other MCTs. The Court is therefore satisfied that queries using U.S.-person identifiers may now be permitted to run against information obtained by the above-described, more limited form of upstream Internet collection, subject to the same restrictions as apply to querying other forms of Section

This is absurd! She has just laid out that there will be some exclusively domestic comms in the collection. Not as much as there was before NSA stopped collecting abouts, but it’ll still be there. So she’s basically permitting domestic communications to be back door searched, which, if they’re found (as she notes), might be kept based on some claim of foreign intelligence value.

And this is where her misunderstanding of the MCT/SCT distinction is her undoing. Bates prohibited back door searching of all upstream data, both that supposedly segregated because it was most likely to have unrelated domestic communications in it, and that not segregated because even the domestic communications would have intelligence value. Bates’ specific concerns about MCTs are irrelevant to his analysis about back door searches, but that’s precisely what Collyer cites to justify her own decision.

She then applies the 2015 opinion, with its input from amicus Amy Jeffress stating that NSA back door searches that excluded upstream collection were constitutional, to claim that back door searches that include upstream collection would meet Fourth Amendment standards.

The revised procedures subject NSA’s use of U.S. person identifiers to query the results of its newly-limited upstream Internet collection to the same limitations and requirements that apply to its use of such identifiers to query information acquired by other forms of Section 702 collection. See NSA Minimization Procedures § 3(b)(5). For that reason, the analysis in the November 6, 2015 Opinion remains valid regarding why NSA’s procedures comport with Fourth Amendment standards of reasonableness with regard to such U.S. person queries, even as applied to queries of upstream Internet collection. (63)

As with her invocation of Bates’ 2011 opinion, she applies analysis that may not fully apply to the question — because it’s not actually clear that the active user restriction really equates newly limited upstream collection to PRISM collection — before her as if it does.

Imposing no consequences

The other area where Collyer’s opinion fails to meet the standards of prior ones is in resolution of the problem. In 2009, when Reggie Walton was dealing with first phone and then Internet dragnet problems, he required the NSA to do complete end-to-end reviews of the programs. In the case of the Internet dragnet, the report was ridiculous (because it failed to identify that the entire program had always been violating category restrictions). He demanded IG reports, which seems to be what led the NSA to finally admit the Internet dragnet program was broken. He shut down production twice, first of foreign call records, from July to September 2009, then of the entire Internet dragnet sometime in fall 2009. Significantly, he required the NSA to track down and withdraw all the reports based on violative production.

In 2010 and 2011, dealing with the Internet dragnet and upstream problems, John Bates similarly required written details (and, as noted, actual volume of the upstream problem). Then, when the NSA wanted to retain the fruits of its violative collection, Bates threatened to find NSA in violation of 50 USC 1809(a) — basically, threatened to declare them to be conducting illegal wiretapping — to make them actually fix their prior violations. Ultimately, NSA destroyed (or said they destroyed) their violative collection and the fruits of it.

Even Thomas Hogan threatened NSA with 50 USC 1809(a) to make them clean up willful flouting of FISC orders.

Not Collyer. She went from issuing stern complaints (John Bates was admittedly also good at this) back in October…

At the October 26, 2016 hearing, the Court ascribed the government’s failure to disclose those IG and OCO reviews at the October 4, 2016 hearing to an institutional “lack of candor” on NSA’s part and emphasized that “this is a very serious Fourth Amendment issue.”

… to basically reauthorizing 702 before using the reauthorization process as leverage over NSA.

Of course, NSA still needs to take all reasonable and necessary steps to investigate and close out the compliance incidents described in the October 26, 2016 Notice and subsequent submissions relating to the improper use of U.S.-person identifiers to query terms in NSA upstream data. The Court is approving on a going-foward basis, subject to the above-mentioned requirements, use of U.S.-person identifiers to query the results of a narrower form of Internet upstream collection. That approval, and the reasoning that supports it, by no means suggest that the Court approves or excuses violations that occurred under the prior procedures.

That is particularly troubling given that there is no indication, even six months after NSA first (belatedly) disclosed the back door search problems to FISC, that it had finally gotten ahold of the problem.

As Collyer noted, weeks before it submitted its new application, NSA still didn’t know where all the upstream data lived. “On March 17, 2017, the government reported that NSA was still attempting to identify all systems that store upstream data and all tools used to query such data.” She revealed that some of the queries of US persons do not interact with “NSA’s query audit system,” meaning they may have escaped notice forever (I’ve had former NSA people tell me even they don’t believe this claim, as seemingly nothing should be this far beyond auditability). Which is presumably why, “The government still had not ascertained the full range of systems that might have been used to conduct improper U.S.-person queries.” There’s the data that might be in repositories that weren’t run by NSA, alluded to above. There’s the fact that on April 7, even after NSA submitted its new plan, it was discovering that someone had mislabeled upstream data as PRISM, allowing it to be queried.

Here’s the thing. There seems to be no way to have that bad an idea of where the data is and what functions access the data and to be able to claim — as Mike Rogers, Dan Coats, and Jeff Sessions apparently did in the certificates submitted in March that didn’t get publicly released — to be able to fulfill the promises they made FISC. How can the NSA promise to destroy upstream data at an accelerated pace if it admits it doesn’t know where it is? How can NSA promise to implement new limits on upstream collection if that data doesn’t get audited?

And Collyer excuses John Bates’ past decision (and, by association, her continued reliance on his logic to approve back door searches) by saying the decision wasn’t so much the problem, but the implementation of it was.

When the Court approved the prior, broader form of upstream collection in 2011, it did so partly in reliance on the government’s assertion that, due to some communications of foreign intelligence interest could only be acquired by such means. $ee October 3, 2011 Memorandum Opinion at 31 & n. 27, 43, 57-58. This Opinion and Order does not question the propriety of acquiring “abouts” communications and MCTs as approved by the Court since 2011, subject to the rigorous safeguards imposed on such acquisitions. The concerns raised in the current matters stem from NSA’s failure to adhere fully to those safeguards.

If problems arise because NSA has failed, over 6 years, to adhere to safeguards imposed because NSA hadn’t adhered to the rules for the 3 years before that, which came after NSA had just blown off the law itself for the 6 years before that, what basis is there to believe they’ll adhere to the safeguards she herself imposed, particularly given that unlike her predecessors in similar moments, she gave up any leverage she had over the agency?

The other thing Collyer does differently from her predecessors is that she lets NSA keep data that arose from violations.

Certain records derived from upstream Internet communications (many of which have been evaluated and found to meet retention standards) will be retained by NSA, even though the underlying raw Internet transactions from which they are derived might be subject to destruction. These records include serialized intelligence reports and evaluated and minimized traffic disseminations, completed transcripts and transcriptions of Internet transactions, [redacted] information used to support Section 702 taskings and FISA applications to this Court, and [redacted].

If “many” of these communications have been found to meet retention standards, it suggests that “some” have not. Meaning they should never have been retained in the first place. Yet Collyer lets an entire stream of reporting — and the Section 702 taskings that arise from that stream of reporting — remain unrecalled. Effectively, even while issuing stern warning after stern warning, by letting NSA keep this stuff, she is letting the agency commit violations for years without any disincentive.

Now, perhaps Collyer is availing herself of the exception offered in Section 301 of the USA Freedom Act, which permits the government to retain illegally obtained material if it is corrected by subsequent minimization procedures.

Exception.–If the Government corrects any deficiency identified by the order of the Court under subparagraph (B), the Court may permit the use or disclosure of information obtained before the date of the correction under such minimization procedures as the Court may approve for purposes of this clause.

Except that she doesn’t cite that provision, nor is there any evidence deficiencies have been corrected.

Which should mean, especially given the way Collyer depends on the prior opinions of Bates and Hogan, she should likewise rely on their practice of treating this as a potential violation of 50 USC 1809(a) to ensure the harm to Americans doesn’t persist. She did no such thing, basically sanctioning the illegal use of back door searches to spy on Americans.

Up until this opinion, I was generally willing to argue for the efficacy of the FISC (even while arguing the job could and should be devolved to district courts for more rigorous testing of the law). But not now. This opinion discredits the entire court.

Last April when Collyer became presiding FISC judge, I pointed to what I considered Rosemary Collyer’s worst FISC decision, which was actually a District Court opinion that permitted the NSA to keep aspects of its upstream problems secret from EFF, which is suing over those same issues. I predicted then that, “I fear she will be a crummy presiding judge, making the FISC worse than it already is.”

In my opinion — as a civil libertarian who has been willing to defend the FISC in the past — with this opinion she has done real damage to any credibility or legitimacy the FISC has.

Update: Latter for former fixed in which choice the Administration picked, h/t CS.

The Documents

Here’s what I Con the Record released.

This heavily redacted report describes a review of NSA’s compliance with 704/705b of Title VII of FISA, the authority NSA uses to spy on Americans who are located overseas (see my report on the 704 problems here). It was conducted from March through August 2015 and reviewed data from January through March 2015. It basically showed there were no compliance mechanisms in place for 704/705b, and NSA couldn’t even reliably identify the queries that had been conducted under the authority. This report is relevant to the reauthorization, because Americans targeted in individual FISA orders are approved (and almost certainly tasked) by default for 702 back door searches. Though the report was obviously done well before the 702 certifications were submitted on September 26, was not noticed to FISC until days before the court would otherwise have approved the certifications in conjunction with the upstream problems.

September 26, 2016 702 Certification Package

ICTR released much if not all of the materials submitted for 702 reauthorization on September 2016. The package includes:

Certification cover filing: This is basically the application, which the metadata reveals is actually two parts merged. It describes the changes to the certificates from the past year, most notably a request to share raw 702 data directly from NSA or FBI to NCTC, some tweaks to the FBI targeting and minimization procedures, and permission for NSA, FBI, and CIA to deviate from minimization procedures to develop a count of how many US persons get collected under 702.

The report also describes how the government has fulfilled reporting requirements imposed in 2015. Several of the reports pertain to destroying data it should not have had. The most interesting one is the report on how many criminal queries of 702 data FBI does that result in the retrieval and review of US person data; as I note in this post, the FBI really didn’t (and couldn’t, and can’t, given the oversight regime currently in place) comply with the intent of the reporting requirement.

Very importantly: this application did not include any changes to upstream collection, in large part because NSA did not tell FISC (more specifically, Chief Judge Rosemary Collyer) about the problems they had always had preventing queries of upstream data in its initial application. In NSA’s April statement on ending upstream about collection, it boasts, “Although the incidents were not willful, NSA was required to, and did, report them to both Congress and the FISC.” But that’s a load of horse manure: in fact, NSA and DOJ sat on this information for months. And even with this disclosure, because the government didn’t release the later application that did describe those changes, we don’t actually get to see the government’s description of the problems; we only get to see Collyer’s (I believe mis-) understanding of them.

Procedures and certifications accepted: The September 26 materials also include the targeting and minimization procedures that were accepted in the form in which they were submitted on that date. These include:

Procedures and certificates not accepted: The materials include the documents that the government would have to change before approval on April 26. These include,

Note, I include the latter two items because I believe they would have had to be resubmitted on March 30, 2017 with the updated NSA documents and the opinion makes clear a new DIRNSA affidavit was submitted (see footnote 10), but the release doesn’t give us those. I have mild interest in that, not least because the AG/DNI one would be the first big certification to FISC signed by Jeff Sessions and Dan Coats.

October 26, 2016 Extension

The October 26 extension of 2015’s 702 certificates is interesting primarily for its revelation that the government waited until October 24, 2016 to disclose problems that had been simmering since 2013.

March 30, 2017 Submissions

The release includes two of what I suspect are at least four items submitted on March 30, which are:

This is the opinion that reauthorized 702, with the now-restricted upstream search component. My comments below largely lay out the problems with it.

April 11, 2017 ACLU Release

I Con the Record also released the FOIAed documents released earlier in April to ACLU, which are on their website in searchable form here. I still have to finish my analysis of that (which includes new details about how the NSA was breaking the law in 2011), but these posts cover some of those files and are relevant to these 702 changes:

Importantly, the ACLU documents as a whole reveal what kinds of US persons are approved for back door searches at NSA (largely, but not exclusively, Americans for whom an individual FISA order has already been approved, importantly including 704 targets, as well as more urgent terrorist targets), and reveal that one reason NSA was able to shut down the PRTT metadata dragnet in 2011 was because John Bates had permitted them to query the metadata from upstream collection.

Not included

Given the point I noted above — that the application submitted on September 26 did not address the problem with upstream surveillance and that we only get to see Collyer’s understanding of it — I wanted to capture the documents that should or do exist that we haven’t seen.

- October 26, 2016 Preliminary and Supplemental Notice of Compliance Incidents Regarding the Querying of Section 702-Acquired Data

- January 3, 2017: Supplemental Notice of Compliance Incidents Regarding the Querying of Section 702-Acquired Data

- NSA Compliance Officer (OCO) review covering April through December 2015

- OCO review covering April though July of 2016

- IG Review covering first quarter of 2016 (22)

- January 27, 2017: Letter In re: DNI/AG 702(g) Certifications asking for another extension

- January 27, 2017: Order extending 2015 certifications (and noting concern with “important safeguards for interests protected by the Fourth Amendment”)

- March 30, 2017: Amendment to [Certificates]; includes (or is) second explanatory memo, referred to as “March 30, 2017 Memorandum” in Collyer’s opinion; this would include a description of the decision to shut down about searches

- March 30, 2017 AG/DNI Certification (?)

- March 30, 2017 DIRNSA Certification

- April 7, 2017 preliminary notice

Other Relevant Documents

Because they’re important to this analysis and get cited extensively in Collyer’s opinion, I’m including:

Timeline

November 30, 2013: Latest possible date at which upstream search problems identified

October 2014: Semiannual Report shows problems with upstream searches during period from June 1, 2013 – November 30, 2013

October 2014: SIGINT Compliance (SV) begins helping NSD review 704/705b compliance

June 2015: Semiannual Report shows problems with upstream searches during period from December 1, 2013 – May 31, 2014

December 18, 2015: Quarterly Report to the FISC Concerning Compliance Matters Under Section 702 of FISA

January 7, 2016: IG Report on controls over §§704/705b released

January 26, 2016: Discovery of error in upstream collection

March 9, 2016: FBI releases raw data

March 18, 2016: Quarterly Report to the FISC Concerning Compliance Matters Under Section 702 of FISA

May and June, 2016: Discovery of querying problem dating back to 2012

May 17, 2016: Opinion relating to improper retention

June 17, 2016: Quarterly Report to the FISC Concerning Compliance Matters Under Section 702 of FISA

August 24, 2016: Pre-tasking review update

September 16, 2016: Quarterly Report to the FISC Concerning Compliance Matters Under Section 702 of FISA

September 26, 2016: Submission of certifications

October 4, 2016: Hearing on compliance issues

October 24, 2016: Notice of compliance errors

October 26, 2016: Formal notice, with hearing; FISC extends the 2015 certifications to January 31, 2017

November 5, 2016: Date on which 2015 certificates would have expired without extension

December 15, 2016: James Clapper approves EO 12333 Sharing Procedures

December 16, 2016: Quarterly Report to the FISC Concerning Compliance Matters Under Section 702 of FISA

December 29, 2016: Government plans to deal with indefinite retention of data on FBI systems

January 3, 2017: DOJ provides supplemental report on compliance programs; Loretta Lynch approves new EO 12333 Sharing Procedures

January 27, 2017: DOJ informs FISC they won’t be able to fully clarify before January 31 expiration, ask for extension to May 26; FISC extends to April 28

January 31, 2007: First extension date for 2015 certificates

March 17, 2017:Quarterly Report to the FISC Concerning Compliance Matters Under Section 702 of FISA; Probable halt of upstream “about” collection

March 30, 2016: Submission of amended NSA certifications

April 7, 2017: Preliminary notice of more query violations

April 28, 2017: Second extension date for 2015 certificates

May 26, 2017: Requested second extension date for 2015 certificates

June 2, 2017: Deadline for report on outstanding issues