How Twelve Years of Warning and Six Years of Plodding Reform Finally Forced FBI to Do Minimal FISA Oversight

Earlier this week, the government released the reauthorization package for the 2018 Section 702 certificates of FISA. With the release, they disclosed significant legal fights about the way FBI was doing queries on raw data, what we often call “back door searches.” Those fights are, rightly, being portrayed as Fourth Amendment abuses. But they are, also, the result of the FISA Court finally discovering in 2018, after 11 years, that back door searches work like some of us have been saying they do all along, a discovery that came about because of procedural changes in the interim.

As such, I think this is wrong to consider “FISA abuse” (and I say that as someone who was very likely personally affected by the practices in question). It was, instead, a case where the court discovered that FBI using 702 as it had been permitted to use it by FISC was a violation of the Fourth Amendment.

As such, this package reflects a number of things:

- A condemnation of how the government has been using 702 (and its predecessor PAA) for 12 years

- A (partial — but thus far by far the most significant one) success of the new oversight mechanisms put in place post-Snowden

- An opportunity to reform FISA — and FBI — more systematically

This post will explain what happened from a FISA standpoint. A follow-up post will explain why this should lead to questions about FBI practices more generally.

The background

This opinion came about because every year the government must obtain new certificates for its 702 collection, the collection “targeted” at foreigners overseas that is, nevertheless, designed to collect content on how those foreigners are interacting with Americans. Last we had public data, there were three certificates: counterterrorism, counterproliferation, and “foreign government,” which is a too-broadly scoped counterintelligence function. As part of that yearly process, the government must get FISC approval to any changes to its certificates, which are a package of rules on how they will use Section 702. In addition, the court conducts a general review of all the violations reported over the previous year.

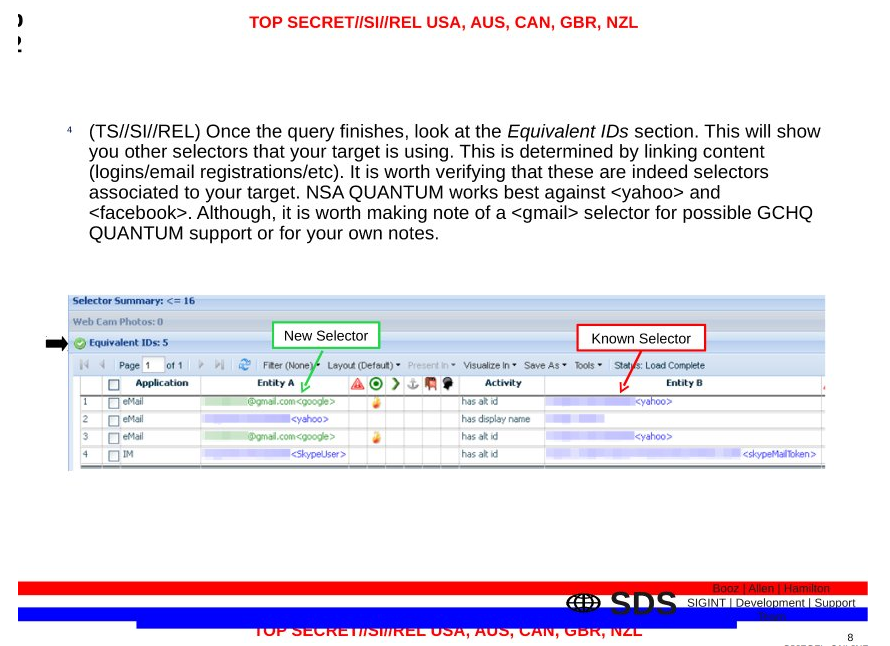

Originally, those certificates included proposed targeting (governing who you can target) and minimization (governing what you can do once you start collecting) procedures; last year was the first year the agencies were required to submit querying procedures governing the way agencies (to include NSA, CIA, National Counterterrorism Center, and FBI) access raw data using US person identifiers. The submission of those new querying procedures are what led to the court’s discovery that FBI’s practices violated the Fourth Amendment.

In the years leading up to the 2018 certification, the following happened:

- In 2013, Edward Snowden’s leaks made it clear that those of us raising concerns about Section 702 minimization since 2007 were correct

- In 2014, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (which had become operational for the first time in its existence almost simultaneously with Snowden’s leaks) recommended that CIA and FBI have to explain why they were querying US person content in raw data

- In 2015, Congress passed the USA Freedom Act, the most successful reform of which reflected Congress’ intent that the FISA Court start consulting amicus curiae when considering novel legal questions

- In 2015, amicus Amy Jeffress (who admitted she didn’t know much about 702 when first consulted) raised questions about how queries were conducted, only to have the court make minimal changes to current practice — in part, by not considering what an FBI assessment was

- In the 2017 opinion authorizing that year’s 702 package, Rosemary Collyer approved an expansion of back door searches without — as Congress intended — appointing an amicus to help her understand the ways the legal solution the government implemented didn’t do what she believed it did; that brought some (though not nearly enough) attention to whether FISC was fulfilling the intent of Congress on amici

- In the 2017 Reauthorization (which was actually approved in early 2018), Congress newly required agencies accessing raw data to submit querying procedures along with their targeting and minimization procedures in the annual certification process, effectively codifying the record-keeping suggestion PCLOB had made over two years earlier

When reviewing the reauthorization application submitted in March 2018, Judge James Boasberg considered that new 2017 requirement a novel legal question, so appointed Jonathan Cederbaum and Amy Jeffress, the latter of whom also added John Cella, to the amicus team. By appointing those amici to review the querying procedures, Boasberg operationalized five years of reforms, which led him to discover that practices that had been in place for over a decade violated the Fourth Amendment.

When the agencies submitted their querying procedures in March 2018, all of them except FBI complied with the demand to track and explain the foreign intelligence purpose for US person queries separately. FBI, by contrast, said they already kept records of all their queries, covering both US persons and non-US persons, so they didn’t have to make a change. One justification it offered for not keeping US person-specific records as required by the law is that Congress exempted it from the reporting requirements it imposed on other agencies in 2015, even though FBI admitted that it was supposed to keep queries not just for the public reports from which they argued they were exempted, but also for the periodical reviews that DOJ and ODNI make of its queries for oversight purposes. FBI Director Christopher Wray then submitted a supplemental declaration, offering not to fix the technical limitations they built into their repositories, but arguing that complying with the law via other means would have adverse consequences, such as diverting investigative resources. Amici Cedarbaum and Amy Jeffress challenged that interpretation, and Judge James Boasberg agreed.

The FBI’s querying violations

It didn’t help FBI that in the months leading up to this dispute, FBI had reported six major violations to FISC involving US person queries. While the description of those are heavily redacted, they appear to be:

- March 24-27, 2017: The querying of 70K facilities “associated with” persons who had access to the FBI’s facilities and systems. FBI General Counsel (then run by Jim Baker, who had had these fights in the past) warned against the query, but FBI did it anyway, though did not access the communications. This was likely either a leak or a counterintelligence investigation and appears to have been discovered in a review of existing Insider Threat queries.

- December 1, 2017: FBI conducted queries on 6,800 social security numbers.

- December 7-11, 2017, the same entity at FBI also queried 1,600 queries on certain identifiers, though claimed they didn’t mean to access raw data.

- February 5 and 23, 2018: FBI did approximately 30 queries of potential sources.

- February 21, 2018: FBI did 45 queries on people being vetted as sources.

- Before April 13, 2018: an unspecified FBI unit queried FISA acquired metadata using 57,000 identifiers of people who work in some place.

Note, these queries all took place under Trump, and most of them took place under Trump’s hand-picked FBI Director. Contrary to what some Trump apologists have said about this opinion, it is not about Obama abuse (though it reflects practices that likely occurred under him and George Bush, as well).

These violations made it clear that Congress’ mandate for better record-keeping was merited. Boasberg also used them to prove that existing procedures did not prevent minimization procedure violations because they had not in these instances.

As he was reviewing the violations, Boasberg discovered problems in the oversight of 702 that I had noted before, based off my review of heavily redacted Semiannual Reports (which means they should have been readily apparent to everyone who had direct access to the unredacted reports). For example, Judge Boasberg noted how few of FBI’s queries actually get reviewed during oversight reviews (something I’ve pointed out repeatedly, and which 702 boosters have never acknowledged the public proof of).

As noted above, in 2017 the FBI conducted over three million queries of FISA-acquired information on just one system, [redacted]. See Supplemental FBI Declaration at 6. In contrast, during 2017 NSD conducted oversight of approximately 63,000 queries in [redacted] and 274,000 queries in an FBI system [redacted]. See Gov’t Response at 36.

Personnel from the Office of Intelligence (OI) within the Department of Justice’s National Security Division (NSD) visit about half of the FBI’s field offices for oversight purposes in a given year. Id at 35 & n 42. Moreover OI understandably devotes more resources to offices that use FISA authorities more frequently, so those offices [redacted] are visited annually, id at 35 n. 42, which necessitates that some other offices go for periods of two years or more between oversight visits. The intervals of time between oversight visits at a given location may contribute to lengthy delays in detecting querying violations and reporting them to the FISC. See, e.g., Jan. 18, 2019, Notice [redacted] had been conducting improper queries in a training context since 2011, but the practice was not discovered until 2017).

He also noted that the records on such queries don’t require contemporaneous explanation from the Agent making the query, meaning any review of them will not find problems.

The FBI does not even record whether a query is intended to return foreign-intelligence information or evidence of crime. See July 13, 2018, Proposed Tr. at 14 (DOJ personnel “try to figure out” from FBI query records which queries were run for evidence of crime purposes). DOJ personnel ask the relevant FBI personnel to recall and articulate the bases for selected queries. Sometimes the FBI personnel report they cannot remember. See July 9, 2018, Notice.

Again, I noted this in the past.

In short, as Boasberg was considering Wray’s claim that the FBI didn’t need the record-keeping mandated by Congress, he was discovering that, in fact, FBI needs better oversight of 702 (something that should have been clear to everyone involved, but no one ever listens to my warnings).

FISC rules the querying procedures do not comply with the law or Fourth Amendment

In response to Boasberg’s demand, FBI made several efforts to provide solutions that were not really solutions.

The FBI’s first response to FISC’s objections was to require General Counsel approval before accessing the result of any “bulk” queries like the query that affected 70K people — what it calls “categorical batch queries.”

Queries that are in fact reasonably likely to return foreign-intelligence information are responsive the government’s need to obtain and produce foreign-intelligence information, and ultimately to disseminate such information when warranted. For that reason, queries that comply with the querying standard comport with § 1801 (h), even insofar as they result in the examination of the contents of private communications to or from U.S. persons. On the other hand, queries that lack a sufficient basis are not reasonably related to foreign intelligence needs and any resulting intrusion on U.S. persons’ privacy lacks any justification recognized by§ 1801 (h)(l). Because the FBI procedures, as implemented, have involved a large number of unjustified queries conducted to retrieve information about U.S. persons, they are not reasonably designed, in light of the purpose and technique of Section 702 acquisitions, to minimize the retention and prohibit the dissemination of private U.S. person information.

But Boasberg was unimpressed with that because the people who’d need to consult with counsel would be the most likely not to know they did need to do so.

He also objected to FBI’s attempt to give itself permission to use such queries at the preliminary investigation phase (before then, FBI was doing queries at the assessment stage).

The FBI may open a preliminary investigation with even less of a factual predicate: “on the basis of information or an allegation indicating the existence of a circumstance” described in paragraph a. orb. above. Id. § II.B.4.a.i at 21 (emphasis added). A query using identifiers for persons known to have had contact with any subject of a full or preliminary investigation would not require attorney approval under § IV.A.3, regardless of the factual basis for opening the investigation or how it has progressed since then.

Boasberg’s Fourth Amendment analysis was fairly cautious. Whereas amici pushed for him to treat the queries as separate Fourth Amendment events, on top of the acquisition (which would have had broad ramifications both within FISA practice and outside of it), he instead interpreted the new language in 702 to expand the statutory protection under queries, without finding queries of already collected data a separate Fourth Amendment event.

Similarly, both Boasberg and the amici ultimately didn’t push for a written national security justification in advance of an actual FISA search. Rather, they argued FBI had to formulate such a justification before accessing the query returns (in reality, many of these queries are automated, so it’d be practically impossible to do justifications before the fact).

Boasberg nevertheless required the FBI to at least require foreign intelligence justifications for queries before an FBI employee accessed the results of queries.

The FBI was not happy. Having been told they have to comply with the clear letter of the law, they appealed to the FISA Court of Review, adding apparently new arguments that fulfilling the requirement would not help oversight and that the criminal search requirements were proof that Congress didn’t intend them to comply with the other requirements of the law. Like Boasberg before them, FISCR (in a per curium opinion from the three FISCR judges, José Cabranes, Richard Tallman, and David Sentelle) found that FBI really did need to comply with the clear letter of the law.

The FBI chose not to appeal from there (for reasons that go beyond this dispute, I suspect, as I’ll show in a follow-up). So by sometime in December, they will start tracking their backdoor searches.

FBI tried, but failed, to avoid implementing a tool that will help us learn what we’ve been asking

Here’s the remarkable thing about this. Something like this has been coming for two years, and FBI is only now beginning to comply with the requirement. That’s probably not surprising. Neither the Director of National Intelligence (which treated its intelligence oversight of FBI differently than it did CIA or NSA) nor Congress had demanded that FBI, which can have the most direct impact on someone’s life, adhere to the same standards of oversight that CIA and NSA (and an increasing number of other agencies) do.

Nevertheless, 12 years after this system was first moved under FISA (notably, two key Trump players, White House Associate Counsel John Eisenberg and National Security Division AAG John Demers were involved in the original passage), we’re only now going to start getting real information about the impact on Americans, both in qualitative and quantitative terms. For the first time,

- We will learn how many queries are done (the FISC opinion revealed that just one FBI system handles 3.1 million queries a year, though that covers both US and non US person queries)

- We will learn that there are more hits on US persons than previously portrayed, which leads to those US persons to being investigated for national security or — worse — coerced to become national security informants

- We will learn (even more than we already learned from the two reported queries that this pertained to vetting informants) the degree to which back door searches serve not to find people who are implicated in national security crimes, but instead, people who might be coerced to help the FBI find people who are involved in national security crimes

- We will learn that the oversight has been inadequate

- We will finally be able to measure disproportionate impact on Chinese-American, Arab, Iranian, South Asian, and Muslim communities

- DOJ will be forced to give far more defendants 702 notice

Irrespective of whether back door searches are themselves a Fourth Amendment violation (which we will only now obtain the data to discuss), the other thing this opinion shows is that for twelve years, FISA boosters have been dismissing the concerns those of us who follow closely have raised (and there are multiple other topics not addressed here). And now, after more than a decade, after a big fight from FBI, we’re finally beginning to put the measures in place to show that those concerns were merited all along.