Ebola Outbreak Receding in Liberia, Still Strong in Sierra Leone

Back in late September, the press had a field day with a mathematical model developed by CDC that estimated that if left unchecked, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa could wind up infecting over 1.4 million people. Almost missed in the hysteria over that high number was the fact that this same model predicted that even with key public health measures (patient isolation, monitoring of at-risk population who had contact with infected people and safe burial practices) falling short of 100% implementation, the outbreak could be brought under control around January of next year.

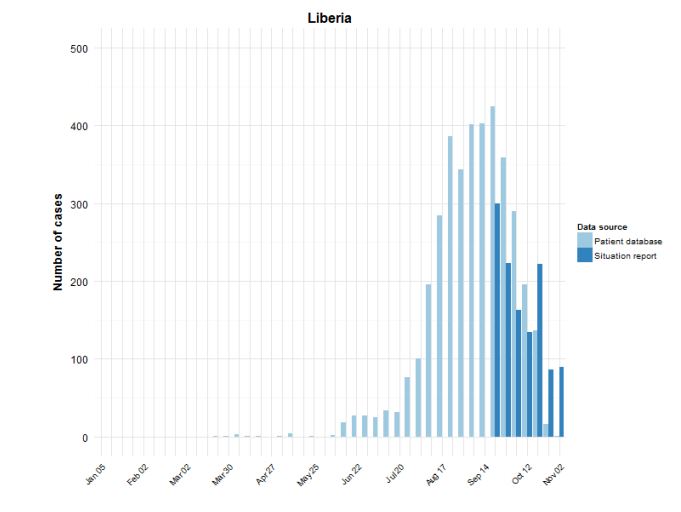

Word has been leaking out for a while now that the rate of new Ebola infections in Liberia is falling. Reports in the Washington Post on October 29 and November 3 told us as much. A chart in the WHO Situation Report for November 5 drives home just how dramatic the decline in new cases has become:

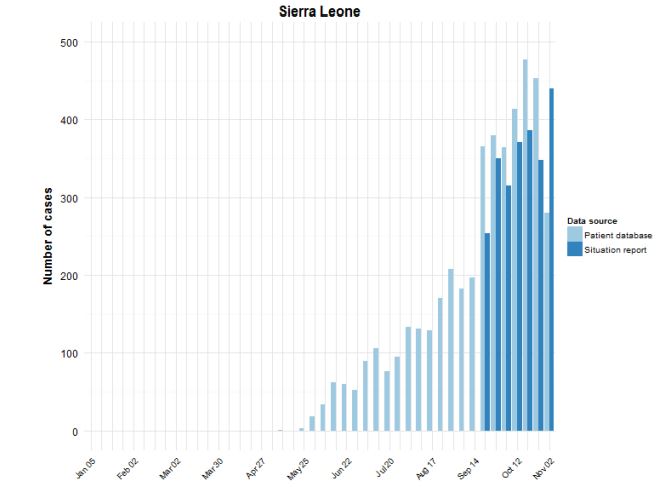

As can be seen in the chart, the rate of new infections for the two most recent weeks is less than one fourth the rate at the peak of the outbreak. Unfortunately, the news for Sierra Leone is not as good. While the rate of new infections may be leveling off, it is not yet falling appreciably:

Digging into the WHO report a bit further, we can find some evidence for how this dramatic drop in new cases has been brought about. We see that 52% of cases are now isolated. The WHO target for December 1 has been set at 70%, with a target of 100% by January 1. When it comes to management of dead bodies, though, the December 1 target has already been surpassed. WHO reports that 87% of the dead are being “managed in a safe and dignified manner” while the targets were set at 70% for December 1 and 100% for January 1. Also, although no benchmarks are reported, WHO states that 95% of registered contacts were reached daily (although in the text of the report, there are suggestions this number may be somewhat overstated).

It should come as no surprise that progress in implementing these basic measures has had a huge impact on bringing down the rate of new infections. It fits perfectly with the CDC mathematical model and it also addresses the known biology of Ebola infections. Patients are most infectious at or near death, so establishing safe burial practices is vitally important. Conversely, identifying infected individuals through daily monitoring of the at-risk population and then isolating infected individuals once symptoms begin means that far fewer people are exposed to people producing large amounts of virus.

Sadly, those who remain exposed are the health care workers who are providing care to those who are infected. Despite shortages of equipment and supplies, WHO and other organizations are doing their best to overcome those shortages and to beef up training to reduce risk to these brave people on the front lines in the work to control the virus. As of this November 5 report, 546 health care workers have been infected, with 310 of them dying. Only four new infections were reported for the week ending November 2, so it is hoped that this rate is also dropping.

Had the alarmists who insisted that this was a new super-strain of Ebola capable of airborne transmission (or even a strain developed in a bioweapons laboratory), it is doubtful that these basic public health measures would have had such a dramatic impact on the rate of new infections. Perhaps those folks can go back to railing about chemtrails or the evils of vaccines, because basic boring science appears to be on the road to controlling the current outbreak before all of mankind succumbs.

In the meantime, we are at about two weeks into the three week incubation period both for anyone “exposed” by Craig Spencer or for Kaci Hickox (or anyone she “exposed”) to show symptoms. No reports of transmission so far, and the odds of any cases showing up are dropping very rapidly from the already very low levels where they started.