How David Addington Hid the Document Implicating George Bush in Illegal Wiretapping

On December 16 and December 20, 2005, respectively — just days after the NYT revealed its existence — EPIC and ACLU FOIAed DOJ for documents relating to George Bush’s (really, Dick Cheney’s) illegal wiretap program (National Security Archive also FOIAed, though more narrowly). Among other documents, they requested, “any presidential order(s) authorizing the NSA to engage in warrantless electronic surveillance.” Yet in spite of the fact that the ACLU was eventually able to get DOJ to cough up some of the OLC memos that provided a legal rationale for the program, no presidential order was ever turned over. I don’t believe (though could be mistaken) it was even disclosed in declarations submitted by Steven Bradbury in the suit.

There’s a very good (and, sadly, legal) reason for that. According to the 2009 NSC draft IG report the Guardian released yesterday, it’s not clear DOJ ever had the Authorization. The White House is exempt from FOIA, and it’s likely that NSA could have withheld the contents of the Director’s safe from any FOIA, which is where the hard copy of the Authorization was kept.

It’s worth looking more closely at how David Addington guarded the Authorization, because it provides a lesson in how a President can evade all accountability for unleashing vast powers against Americans, and how the National Security establishment will willingly participate in such a scheme without ensuring what they’re doing is really legal.

The IG report describes the initial Authorization this way:

On 4 October 2001, President George W. Bush issued a memorandum entitled “AUTHORIZATION FOR SPECIFIED ELECTRONIC ACTIVITIES DURING A LIMITED PERIOD TO DETECT AND PREVENT ACTS OF TERRORISM WITHIN THE UNITED STATES.” The memorandum was based on the President’s determination that after the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, an extraordinary emergency existed for national defense purposes.

[snip]

The authorization specified that the NSA could acquire the content and associated metadata of telephony and Internet communications for which there was probable cause to believe that one of the communicants was in Afghanistan or that one communicant was engaged in or preparing for acts of international terrorism. In addition, NSA was authorized to acquire telephone and Internet metadata for communications with at least one communicant outside the United States or for which no communicant was known to be a citizen of the United States. NSA was allowed to retain, process, analyze and disseminate intelligence from the communications acquired under the authority.

And while the NSA IG report doesn’t say it, the Joint IG Report on the program (into which this NSA report was integrated) reveals these details:

Each of the Presidential Authorizations included a finding to the effect that an extraordinary emergency continued to exist, and that the circumstances “constitute an urgent and compelling governmental interest” justifying the activities being authorized without a court order.

Each Presidential authorization also included a requirement to maintain the secrecy of the activities carried out under the program.

David Addington’s illegal program

While the Joint report obscures all these details, the NSA IG report makes clear that Dick Cheney and David Addington were the braintrust behind the program.

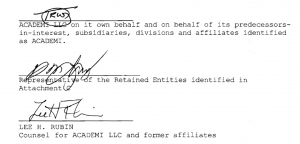

The Counsel to the Vice President used [a description of SIGINT collection gaps provided by Michael Hayden] to draft the Presidential authorization that established the PSP.

Neither President Bush nor White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales wrote this Authorization. David Addington did. Read more →