On Same Day Robert McBride’s Firing Is Reported, Stan Woodward “Errs” His Grievances

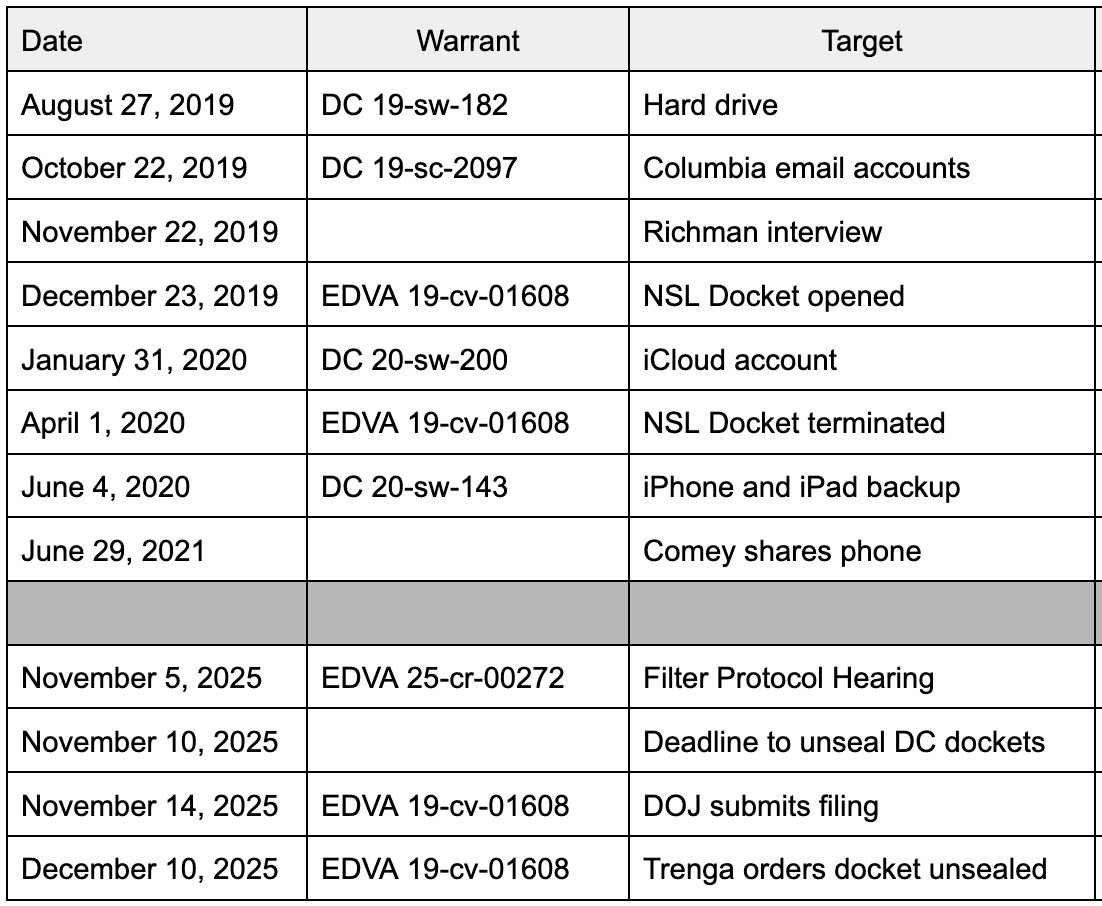

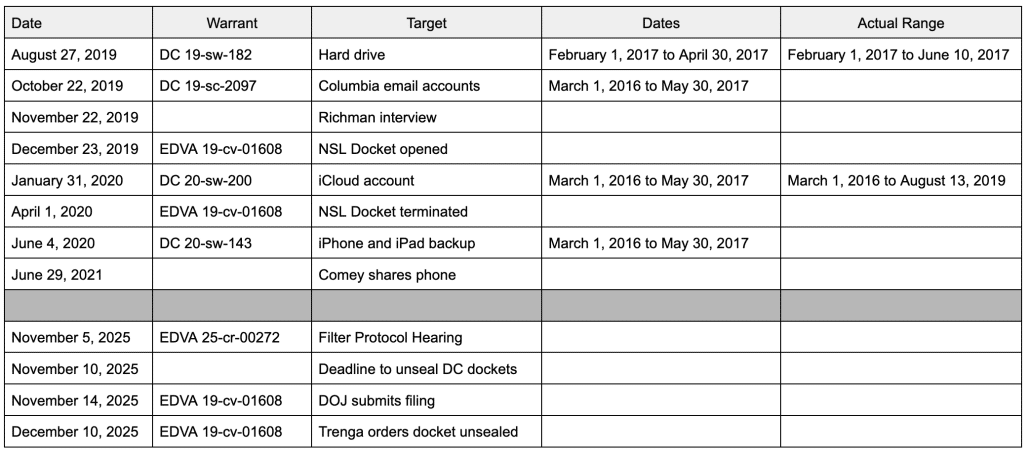

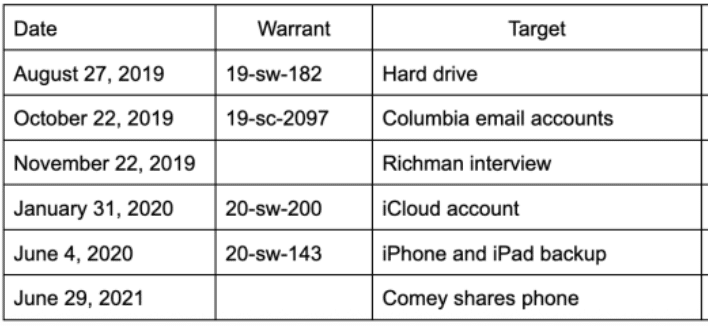

A slew of outlets — starting with MS and including NYT but not including ABC, which usually gets the details right — have reported the firing of Robert McBride because, the MS headline claims, he “declined to pursue James Comey case.” All suggested that, even with the appeal of Lindsey Halligan’s firing before the Fourth Circuit (the Fourth just granted DOJ’s request to stall two weeks and keep the two appeals consolidated), McBride’s sins involved recharging the case in EDVA, even though DOJ abandoned its attempts to reindict Letitia James (on the mortgage fraud; now they’re pursuing hairdresser fraud) before it appealed.

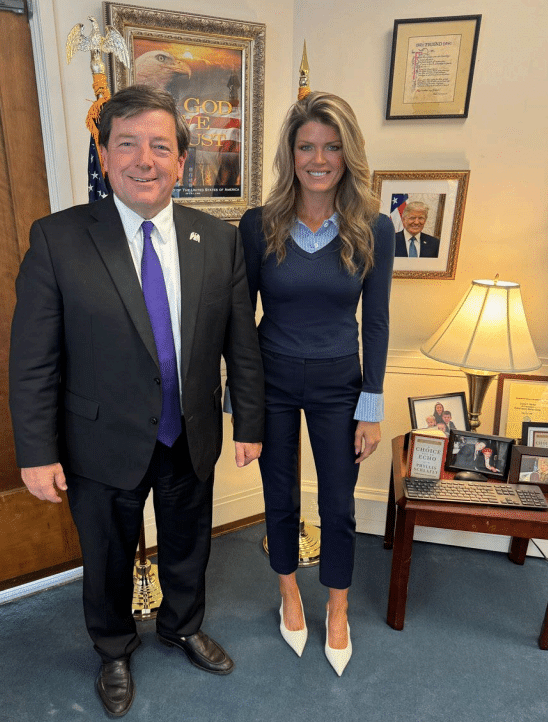

No one mentioned news of the firing happened on the day the SDFL grand jury convenes, or the Comey-related role McBride has been willingly playing, as the single non-defense lawyer litigating Dan Richman’s efforts to get his files returned.

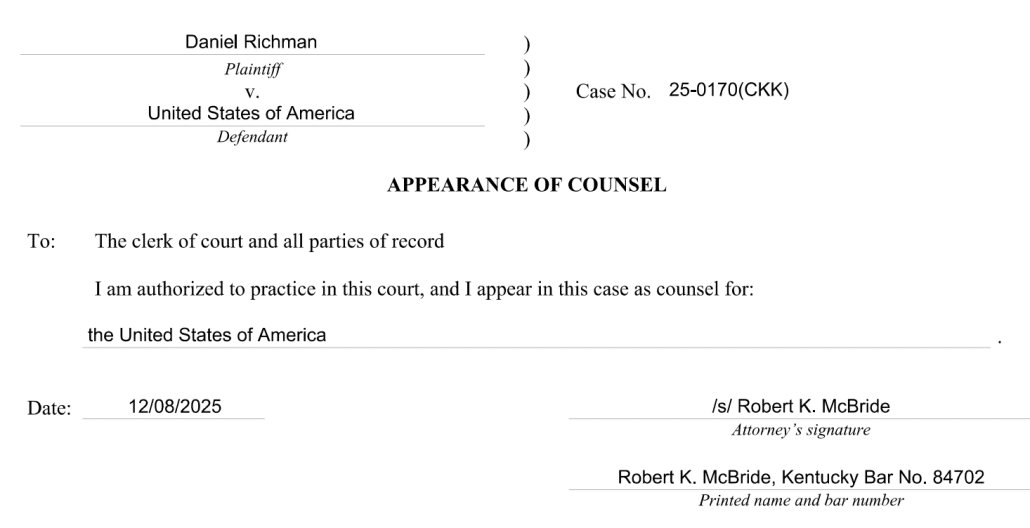

Associate Attorney General Stanley Woodward’s latest prank — an “erring” of grievances — may explain McBride’s firing.

When last we checked in on the Richman litigation before Christmas, after spending some time making sure that someone had ethical skin in her courtroom, Colleen Kollar-Kotelly attempted to juggle the genuinely complex issues before her, granting one after another notice of defiances masquerading as emergency motions for delay for the government, before — seemingly — issuing a final order on December 23, requiring the government to turn over all materials it had, but allowing it to delete the single no-longer classified file they used to obtain the materials back in 2017.

For the foregoing reasons, the Court shall GRANT IN PART the Government’s [22], [33] Emergency Motions to Clarify and Modify the Court’s Order and AMEND its [20] Order dated December 12, 2025, to make explicit that the Government may delete the purportedly classified document identified in 2017 from any material that it returns to Petitioner Richman. Because the Government has not shown that it has a lawful right to retain and use any of the materials at issue, the Court shall not otherwise alter its Order to relieve the Government from its obligation to return those materials to Petitioner Richman.

The next day, in a filing signed by Todd Blanche, Lindsey Halligan, and McBride, DOJ asked for an emergency extension. Again. Because of the holiday, they couldn’t technically remove that single classified file they supposedly removed back in 2017.

7. However, because of significant operational constraints caused by the imminent Christmas and New Year’s holidays (i.e., the lack of sufficient, technically qualified Government personnel in the Washington, DC area for the remainder of this week and the next), which make the current compliance deadline fall a mere one business day after the Court’s revised clarifying order, the Government anticipates that it will not be able to review all electronic storage devices containing classified information, delete that information, and return those devices to Richman’s counsel by December 29, 2025.

But on Christmas Eve, they were going to delete that file.

Days later Kollar-Kotelly granted that extension while reiterating that they only thing they were allowed to do was to delete that file.

Then Stan Woodward, the guy who defended all the people covering up Trump’s crimes across two criminal investigations, got involved. Without filing a notice of appearance — so Stan has no ethical skin in this game — On January 2, he effectively indicated that DOJ was going to defy Kollar-Kotelly’s order, because deleting that single classified file would destroy the forensic copy of this.

In the days since the Court last extended the foregoing deadline, the undersigned counsel has endeavored to negotiate in good faith with counsel for Petitioner-Movant the particulars of the parties’ understanding of what compliance with the Court’s Orders requires. For example, classified information cannot be deleted from the government’s forensic copy of electronic media without the destruction of the entire media. Thus, although the Court’s Orders, “permit the Government to permanently delete a single classified document from the material seized from Petitioner Richman’s personal computer hard drive . . . from any of these materials before returning them to Petitioner Richman,” ECF No. 41 at 2, such limited deletion of classified information from a forensic image is not technologically feasible.

Now, this may be bullshit. Richman’s lawyers, at least, understand that DOJ still retains the actual hard drive, not a forensic copy. The reasons why they believe that are mostly redacted, but it appears the serial number on the subsequent search warrants matches the serial number of Richman’s original hard drive, meaning they kept the original and gave him a different hard drive.

Nicholas Lewin at least believes DOJ gave Richman a different hard drive back in 2017, effectively stealing his actual hard drive in defiance of the consent he gave.

If so, it’s not a forensic image.

And, anyway, someone should have started asking — I know I did — why the Associate Attorney General and the President’s third defense attorney involved in just this matter got involved in a seemingly minor issue that seemed to be settled at all.

Nevertheless, for reasons (probably professional comity) that I cannot fathom, Richman’s lawyers agreed to discuss how DOJ could get out of complying with Kollar-Kotelly’s order, so long as DOJ promised it wouldn’t do anything with his stuff. Kollar-Kotelly granted that extension too.

At that point, it was clear to me at least, DOJ had succeeded in dicking Kollar-Kotelly around long enough to facilitate a different grand jury — the one in SDFL and possibly convened before Aileen Cannon — to issue a warrant and therefore create competing orders from two District Courts.

Then, last night at 7:50PM, and so well after McBride was fired, Stan Woodward asked for another extension. With a flourish, the guy who badly struggled with basic technical issues during the stolen documents case elaborated on his blather about forensic copies (again, if it’s true that DOJ kept Richman’s original hard drive, then this is all bullshit).

The Parties dispute what the Court has authorized the United States to delete. However, when a device contains classified information the only way to properly remove that information is to destroy the device and all the information on that device. Put differently, the United States cannot delete just the documents containing classified material from the device. Further complicating matters is the fact that regardless of the presence of classified information, a single file cannot be deleted from a forensic copy of a device. Either the entire forensic copy is deleted or none of it is. Nevertheless, Petitioner-Movant has requested the United States not destroy any devices containing classified material absent further Order of the Court. The United States will honor this request and hopes the Parties can propose language for the Court’s consideration promptly.

But the bulk of Woodward’s filing consisted of, as he described it, “erring” his grievance that — around the time McBride may have disappeared –Richman’s lawyers did not immediately respond to Woodward’s attempts to keep a full set of Richman’s data on January 10.

To that end, the United States provided counsel for Petitioner-Movant a draft joint consent motion proposing modification to the Courts Orders on December 31, 2025, following a call to outline the contours of the same with Petitioner-Movant’s counsel the previous day. On January 5, 2025, Petitioner-Movant’s counsel wrote to question whether an agreement between the Parties was conceivable. The United States requested a call with counsel for Petitioner-Movant the next day, January 6, 2026, but counsel for Petitioner-Movant advised they were unavailable before January 8 for such a call. Given the desire for the United States to promptly resolve this matter, the United States implored counsel for Petitioner-Movant to provide a redline to the proposed consent motion, which counsel for Petitioner-Movant did after business hours on January 8. The United States provided further edits to the joint motion the next morning, on January 9. Since that time – and at the time of this filing – the United States has not received feedback on that draft despite representations that such feedback would be forthcoming on January 10.

Despite the undersigned representing to Petitioner-Movant’s counsel multiple times a desire to resolve this matter promptly, no agreement has been reached. The undersigned does not err this grievance lightly, but does so only out of respect for the Court’s deadline and out of regret for not seeking an extension earlier. [my emphasis]

It’s Richman’s fault, Woodward suggests by claiming grievance, not his own.

I have no idea whether Kollar-Kotelly saw the news that the only line prosecutor who filed a notice of appearance before her got fired in the middle of all this, but she seemed unimpressed that Woodward was erring grievances about delay when he filed his motion for an extension well after hours the day of his deadline.

The Court is in receipt of the Government’s Unopposed 45 Motion for Extension of Time. Given the late hour of this filing, which the Court received at 7:50 p.m. this evening, and with the understanding that the Government has complied with the Court’s 20 Order (as clarified and amended) in all respects except for the narrow unresolved issues identified in the 45 Motion, it is ORDERED that the deadline for the Attorney General or her designee to certify compliance with the Court’s Order is STAYED through January 13, 2026. The Court otherwise DEFERS RULING on the Government’s 45 Motion for Extension of Time. The Court shall resolve the 45 Motion by further order in due course.

She’s going to deal with it today.

But by firing McBride (who would have had cause to talk with EDVA judges about the supposedly intact copy DOJ stored in their SCIF, another of the crimes for which he was fired), there’s no longer anyone with real ethical skin in the game before Kollar-Kotelly, just Donald Trump’s defense attorneys, all of whom have chummy ties with Aileen Cannon.

Effectively, the promises not to access Dan Richman’s stuff have become virtually unenforceable.

Update: I missed that Stan Woodward did file a notice of appearance on January 2. It remains true that Trump’s defense attorneys likely aren’t that worried about bar complaints.

Update: Kollar-Kotelly has given DOJ a week from today.

MINUTE ORDER: Upon further consideration of the Government’s 45 Motion for Extension of Time, it is ORDERED that the Government’s 45 Motion is GRANTED to the following extent: It is ORDERED that the deadline for the Attorney General or her designee to certify to this Court, with specificity, that the Government has complied with this Court’s 20 Order dated December 12, 2025, as clarified and modified by any subsequent Order of this Court, including the provisions regarding both the return of certain materials to Petitioner Richman and the deposit of certain materials in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, is EXTENDED to 5:00 p.m. ET on January 20, 2026.It is further ORDERED that the parties shall file a joint status report, no later than 9:00 a.m. ET on January 16, 2026, advising the Court of (1) the progress of the Government’s efforts to comply with the Court’s 20 Order, and (2) whether Petitioner Richman possesses a copy of any files or other materials that the Government proposes to delete or destroy on the basis that they are stored on a device or in an image that contains classified information.As previously ordered, the Government and its agents shall not access Petitioner Richman’s covered materials, except for the limited purpose of deleting the purportedly classified memorandum already identified in the record, or share, disseminate, disclose, or transfer those materials to any person, without first seeking and obtaining leave of this Court. Signed by Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly on 01/13/2026.