The MalwareTech Poker Hand: Calling DOJ’s Bluff

With a full poker hand’s worth of filings on Friday, MalwareTech’s (AKA Marcus Hutchins) lawyers are finally revealing the main thrust of their defense. The five filings are:

- A motion for a bill of particulars, basically demanding that the government reveal what 10 computers Hutchins and his alleged co-conspirator conspired and intended to damage

- A motion to suppress the statements Hutchins made after he was arrested, requesting an evidentiary hearing, based on the fact that Hutchins was high and exhausted and didn’t know US law about Miranda warnings

- A motion to dismiss the indictment, arguing on three different grounds that,

- The CFAA charges (one and six) don’t allege any intent to cause damage to a protected computer (because the malware in question steals data, but doesn’t damage affected computers)

- The Wiretapping charges (two through five) don’t allege the use of a device as defined under the Wiretap Act, but instead show use of software

- The sales-related charges (one, five, and six) conflate the sale of malware with the ultimate effect of it

- A motion to dismiss the indictment for improper extraterritorial application and venue, effectively because this case should never have been charged in the US, much less Milwaukee

- A motion to dismiss charges two and six based on suspected improper grand jury instruction failing to require intentionality

Effectively, these five motions (which are likely to meet with mixed success, but even where they’re likely to fail, will lay the groundwork for trial) work together to sustain an argument that Hutchins should never have been charged with these crimes in the US, and that FBI may have cheated a bit to get the incriminatory statements that might let them sustain the prosecution.

I laid out the general oddity of these charges here, and the background to the Miranda challenge and grand jury instructions here, here, and here.

Hutchins was high and tired, not drunk, for his one minute Miranda warning

While I don’t expect the Miranda challenge (item 2) to be effective on its face, I do expect it to serve as groundwork for a significant attempt to discredit Hutchin’s incriminatory statements at trial. This motion provides more detail about why his defense thinks it will be an effective tactic. It’s not just that Hutchins is a foreigner and couldn’t be expected to know how US Miranda works, or that the FBI only documented that they asked Hutchins if he had drinking alcohol four months after the arrest (as I laid out here). But as the motion notes, the FBI doesn’t claim to have asked whether he was exhausted or otherwise intoxicated.

According to an FBI memorandum, before “initiating a post arrest interview,” an agent asked Mr. Hutchins if he had been drinking that day, and he responded that he had not. That memorandum, written over four months after the arrest, then states that the agent asked Mr. Hutchins “if has [sic] in a good state of mind to speak to the FBI Hutchins agreed.” Mr. Hutchins did not understand it to be an inquiry as to whether he had used drugs or was exhausted.

The initial 302 of the interrogation records Hutchins telling the agents that he had been partying and not sleeping.

Mr. Hutchins discussed his partying while in Las Vegas, as well as his lack of sleep, during the interrogation.

The motion admits that he had been using drugs (of unspecified type) the night before.

As Mr. Hutchins sat in the airport lounge, he was not drinking, but he was exhausted from partying all week and staying up the night before until the wee hours. He had also used drugs.

Nevada legalized the recreational use of marijuana effective July 2017, so if he was still high during this interview, he might have been legally intoxicated under state (but not federal) law. And there’s not a lick of evidence that the FBI asked him about that.

After laying out that the FBI has no record of asking Hutchins whether he was sober (rather than just not drunk), the motion reveals that the FBI couldn’t decide at what time it gave Hutchins his Miranda warning.

An FBI Advice of Rights form sets forth Miranda warnings and reflects Mr. Hutchins’ signature. It is dated August 2, 2017, but the time it was completed includes two crossed out times, 11:08 a.m. and 2:08 p.m., and one uncrossed out time, 1:18 p.m. (which is one minute after the FBI log reflects Mr. Hutchins’ arrest, as noted above).

And as noted before, and reiterated here, the FBI didn’t record that part of his interview.

The motion notes that if the final, current record of the time of warning is correct, then the Miranda warning, including any discussion of how US law differs from British law, took place in the minute after he was whisked away from this gate.

Hutchins recently tweeted that he “slept the entire time I was in prison,” which while not accurate (he was neither in prison nor in real solitary), would otherwise corroborate the claim he was exhausted.

The government’s cobbled case on intentionality and computer law

Items 3 and 5, arguing the law is inappropriately applied and specifically not instructed correctly with regards to two charges, work together to argue that the government has cobbled together charges against Hutchins via misapplying both CFAA and Wiretap law, and in turn using conspiracy charges and misstating requisite intentionality to be able to get at Hutchins.

As I’ve noted, Hutchins’ lawyers have been arguing for some time that the government may not have properly instructed the grand jury on the intentionality required under charges 2 and 6. At a hearing in February, Magistrate Nancy Joseph showed some sympathy to this argument (though is still reviewing whether the defense should get the grand jury instructions). As I noted in that post, whereas the government once claimed it would easily fix this problem by getting a superseding indictment (possibly larding on new charges), they seem to have lost their enthusiasm for doing so.

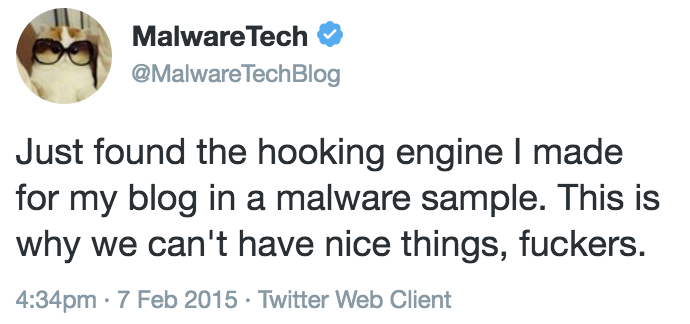

It’s the combination of the rest of the legal challenge that I find more interesting. The challenge will interact with recent innovations in charging other foreign hackers, especially a bunch of Russians that will make DOJ especially defensive of this challenge. But the motions all cite Seventh Circuit precedent closely, so I’m not sure whether that matters.

Ultimately, this motion makes roughly the same arguments that Orin Kerr made as soon as the indictment came out. As he introduced his more thorough explanation in August,

This raises an interesting legal question: Is it a crime to create and sell malware?

The indictment asserts that Hutchins created the malware and an unnamed co-conspirator took the lead in selling it. The indictment charges a slew of different crimes for that: (1) conspiracy to violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act; (2) three counts of violating 18 U.S.C. 2512, which prohibits selling and advertising wiretapping devices; (3) a count of wiretapping; and (4) a count of violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act through accomplice liability — basically, aiding and abetting a hacking crime.

Do the charges hold up? Just based on a first look at the case, my sense is that the government’s theory of the case is fairly aggressive. It will lead to some significant legal challenges. It’s hard to say, at this point, how those challenges will play out. The indictment is pretty bare-bones, and we don’t have all the facts or even what the government thinks are the facts. So while we can’t say that this indictment is clearly an overreach, we can say that the government is pushing the envelope in some ways and may or may not have the facts it needs to make its case. As always, we’ll have to stay tuned.

Kerr is not flaming hippie, so I assume that these arguments will be rather serious challenges for the government and I await the analysis of this challenge by more Fourth Amendment lawyers. But as he suggested back in August, Hutchins’ team may well be right that this indictment is an overreach.

DOJ still hasn’t explained why it charged Hutchins for a crime with no known US victims

While requests for Bill of Particulars (basically, a request for more details about what the government is claiming broke the law) are usually unsuccessful, this one does two interesting things. It asks the government for proof of damage, including proof of which ten computers got damaged.

Mr. Hutchins asks that the government be required to particularize the “damage” it intends to offer into evidence at trial in connection with the alleged violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act by the two defendants. Mr. Hutchins also asks that the government be required to particularize the “10 or more protected computers” to which it contends the defendants conspired and attempted to cause “damage.”

Whether the motion itself is successful or not, demanding proof that ten computers were damaged helps support the challenge to the two CFAA charges based on whether stealing credentials amounts to damage. It also lays the groundwork for the motion made explicitly in item 4 — that Hutchins should never have been charged in the US, much less Wisconsin.

As I laid out in this piece, it appears likely that charges against Hutchins arose out of back door searches done as part of the investigation into who “MalwareTech” was after he sinkholed WannaCry. For whatever reason (probably because the government thought Hutchins could inform on someone, possibly related to either WannaCry itself or Kelihos), the government decided to cobble together a case against Hutchins consisting — by all appearances — entirely of incidental collection so as to coerce him into a plea deal. When he got a team of very good lawyers and then bail, that put a lot more pressure on the appropriateness of the charges in the first place.

So now, eight months after Hutchins was arrested, we’re finally getting to that question of why the US government decided to charge him for a crime that even DOJ didn’t claim had significant US victims.

The motion starts by noting that Hutchins didn’t do most of the acts alleged, his co-defendant Tran (whom the government has shown little urgency in extraditing) did. But even for Tran’s acts (basically marketing and selling the malware), there’s no affirmative tie made to Wisconsin.

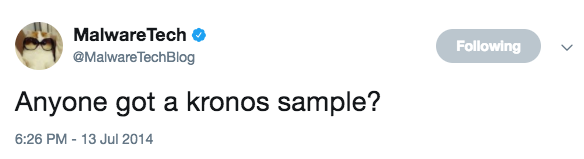

As part of the purported conspiracy, the indictment alleges that Mr. Hutchins created the Kronos software, described as “a particular type of malware that recorded and exfiltrated user credentials and personal identifying information from protected computers.” (Id. ¶¶ 3(e), 4(a).) It also alleges that Mr. Hutchins and his co-defendant later updated Kronos. (Id. ¶ 4(d).)

All other alleged overt acts in furtherance of the purported conspiracy pertain solely to Mr. Hutchins’ co-defendant. Per the indictment, the codefendant (1) used a video posted to YouTube to demonstrate how Kronos worked, (2) advertised Kronos on internet forums, (3) sold a version of Kronos, and (4) offered crypting services for Kronos. (Id. ¶¶ 4(b), (c), (e), (f), (g).)

Aside from a bare allegation that each offense was committed “in the state and Eastern District of Wisconsin and elsewhere,” the indictment does not describe any connection to this District.

While the government has long suggested that the case is in EDWI because an FBI agent located there bought a copy of Kronos, the motion suggests Hutchins’ team hasn’t even seen good evidence of that yet.

Here, the indictment reflects that Mr. Hutchins was on foreign soil, and any acts he performed occurred there. There is no indication that damage was caused in the Eastern District of Wisconsin—or, indeed, that any damage occurred at all. At best, a buyer was present in this District. But the buyer would then need to use Kronos to cause damage in the District for venue to lie. Nothing [i]n the indictment supports that conclusion.

The charging of two foreigners is all the more problematic on the four wiretapping charges, given that (unlike CFAA), Congress did not mean to apply it to foreigners.

There is evidence that Congress intended the CFAA—the legal basis of Counts One and Six—to have extraterritorial application. The CFAA prohibits certain conduct with respect to “protected computers,” 18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(2)(B), and the legislative history shows that Congress crafted the definition of that term with foreign-based attackers in mind. S. Rep. 104-357, at 4-5 (1996).

The Wiretap Act—at issue in Counts Two through Five—is different, though. That law does not reflect a clear congressional mandate that it should apply extraterritorially. Accordingly, courts have repeatedly found that it “has no extraterritorial force.” Huff v. Spaw, 794 F.3d 543, 547 (6th Cir. 2015) (quoting United States v. Peterson, 812 F.2d 486, 492 (9th Cir. 1987)).

There is a great deal of precedent to establish venue based on where a federal agent bought something. Indeed, the main AlphaBay case against Alexandre Cazes consisted of that (remember that Kronos was ultimately sold on AlphaBay). But that case was based on the illegal sale of drugs and ATM skimmers, not software, which given the challenge to the CFAA and Wiretapping application here, might make the EDWI purchase of Kronos insufficient to justify venue here.

I’m not sure whether this motion will succeed or not. But one way or another, given that the defense appears to have seen no real basis for venue here, this motion may serve as critical groundwork for what appears to be a justifiable argument that this case should never have been charged in the US.

I keep waiting for DOJ to give up this case in the face of having to argue that the guy who sinkholed WannaCry should be prosecuted because he refused to accept a plea deal on charges with no known US victims. But they’re probably too stubborn to do that.

Update: Corrected Joseph’s name. h/t GM.