“Hype:” How FBI Decided Searching 702 Content Was the Least Intrusive Means

Former FBI Special Agent Asha Rangappa has a defense of back door searches at Just Security that (unlike most defenses of 702) actually takes on those searches as practiced in most problematic way at FBI, rather than as done in much more controlled fashion at NSA.

FBI does federated searches

I think she nitpicks a few issues. For example, she claims that back door opponents claim there is a “stand-alone computer in the middle of each FBI office with a big sign that reads ‘702 DATABASE ‘” but then goes on to claim “FBI uses one database for all of its investigative functions,” even while admitting that the FBI really does “federated queries” of multiple repositories. The distinction — particularly given that we know the database comes with access limits tied to job function — could offer solutions to concerns about 702 data (including providing access to just metadata, a proposal I’m not a fan of but one she attacks in the post). She also ignores the FBI’s use of “ad hoc databases” that have posed access and data protection concerns in the past. Which is to say, the technical realities of how FBI Agents access this data soup are more complex than she lays out, and those complexities should be part of the discussion because they present additional risks and opportunities.

FBI’s raw data will be US-person focused

Rangappa minimizes what percentage of raw data obtained by FBI would include US person contact.

According to FBI Director Christopher Wray, the FBI receives about 4.3 percent of the NSA’s total collection – and since not every incidental communication will necessarily involve an USPER, the number of communications involving Americans are likely less than that.

While the FBI does have global investigations, the FBI is going to have few full investigations that have no domestic component. Investigations focused on US victims (say a US company hacked by Russian or Chinese state actors) won’t include many US interlocutors, but the other most likely 702 related investigations would all be focused on international communications: who suspected extremists were talking to in the US, what Iranians were buying dual use or other proliferation products, including from US companies, which Americans that Chinese scientists or Russian businessmen were engaging with closely. The 5,000 or so targets sucked into FBI would be the 5,000 targets in most frequent contact with Americans, by design. That has been the entire justification for this collection program since its inception as Stellar Wind.

And — as Ron Wyden recently made clear — it is permissible to target a foreigner if collecting on a US person is one purpose of the targeting, so long as the foreigner is targetable in his own right. Indeed, we can probably point to examples where that happened. That’s going to increase the US content pulled in with those 5,000 targets.

702 can target a whole bunch of selectors

And I believe this is misleading.

PRISM allows the NSA to target non-U.S. persons reasonably believed to be located abroad based on “selectors” – like an email address or a phone number (but not keywords or names) – which will reasonably return foreign intelligence information.

It is true that upstream collection doesn’t use keywords (and has halted about collection altogether). It is true that the most common selector provided in a directive to Google will be an email address. But there are a slew of other kinds of selectors that NSA and FBI can target. That includes IP addresses, which given the 2014 exception means entirely domestic communications can be collected. Even ignoring the targeting of IP addresses that Americans are known to also use (which will come into FBI’s possession a different way), the collection on chat room IPs, just as one example, might suck up a lot more US person content than individual emails might. And the FBI can also search for things like cookies or encryption tools, which will pull in different kinds of content.

FBI’s queries are not all routinely audited

I think Rangappa overstates the tracking of queries and makes an outright error when she claims that backdoor searches are “routinely audited.”

Every query, furthermore, is documented and placed in a case file. (If we learned anything from James Comey, it’s that the FBI puts everything down on paper.) In fact, every query conducted by the FBI is recorded and must be traceable back to an authorized purpose and a case file. Agent queries are routinely audited, and a failure of an agent to provide an authorized purpose for conducting a query can be grounds for sanctions, suspension, or even termination.

She overstates the tracking of queries because by design there’s not a case file for many of the queries in question, because they’re done at the assessment stage. Moreover, if the FBI tracked its queries as well as Rangappa claims, it could provide documentation of what was going on to oversight bodies, but it has persistently claimed it could not do so, not in public, and not even in private.

More importantly, the FBI’s use of 702 is simply not audited adequately. That’s true, in part, because in 2012-2013, FBI moved much of its FISA activity to field offices, and not every field office gets audited every six months.

During this reporting period, however, FBI transitioned much of its dissemination from FBI Headquarters to FBI field offices. NSD is conducting oversight reviews of FBI field offices use of these disseminations, but because every field office is not reviewed every six months, NSD no longer has comprehensive numbers on the number of disseminations of United States person information made by FBI.

In 2015 — the most recent period for which we’ve gotten a Semiannual Report — NSD only reviewed minimization at 15 field offices (and ODNI did not attend all of these).

During these field office reviews, NSD also audits a sample of FBI personnel queries in systems that contain unminimized Section 702 collection. As detailed in the attachments to the Attorney General’s Section 707 Report, NSD conducted minimization reviews at 15 FBI field offices during this reporting period and reviewed cases involving Section 702-tasked facilities.

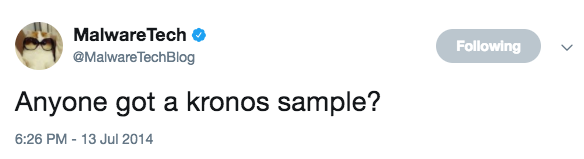

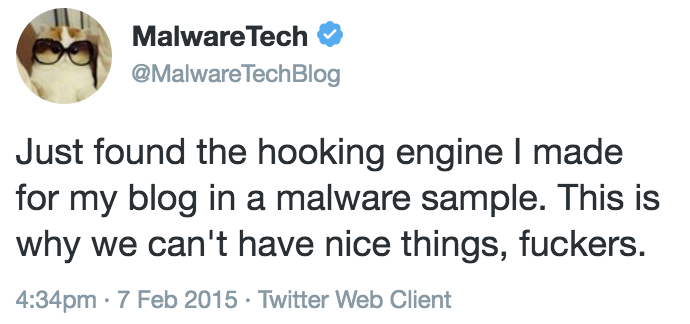

FBI has 56 field offices. And while I’m confident that NSD focuses its 702 reviews on the offices that work with FISA most often — places like DC, NY, LA, SF, and places with significant foreign population, like Detroit and Minneapolis — that means that when a field office that doesn’t use FISA often (say, if an Agent in Milwaukee were researching a hacker named MalwareTech), a combination of inexperience and lax oversight might be especially likely to result in problems. And note, in any office, just a sample of queries gets reviewed, as the government explained to FISC last year, and the tracking isn’t detailed enough to figure out what occurred with a query without talking to the Agent who did it.

Additionally, NSD conducts minimization reviews in multiple FBI field offices each year. As part of these minimization reviews, NSD and FBI National Security Law Branch have emphasized the above requirements and processes during field office training. Further, during the minimization reviews, NSD audits a sample of queries performed by FBI personnel in the databases storing raw FISA-acquired information, including raw section 702-acquired information. Since December 2015, NSD has reviewed these queries to determine if any such queries were conducted solely for the purpose of retaining evidence of a crime. If such a query was conducted, NSD would seek additional information from the relevant FBI personnel as to whether FBI personnel received and reviewed section 702-acquired information of or concerning a U.S. person in response to such a query.

Notably, the one case where FBI reported a criminal return on a criminal search in 702 information only got reported after NSD did follow-up questioning. So yeah, NSD spends 4 days at Main Justice reviewing this stuff and goes to 27% of the field offices every six months, but that’s a far cry from “routinely auditing” queries.

The importance of investigative levels

The most remarkable thing about Rangappa’s post, however, is how well she exhibits the absurdity of what really goes on here. She correctly states — as I reported here — that FBI only obtains 702 content in full investigations. And she provides a short description of FBI’s three investigative levels.

Specifically, the NSA passes on to the FBI information collected on selectors associated with “Full Investigations” opened by the FBI. Full Investigations are the most serious class of investigations within the Bureau, and require the most stringent predicate to open: There must be an “articulable factual basis” that a federal crime has occurred or is occurring or a threat to national security exists. (Two other investigative classifications, Preliminary Investigations and Threat Assessments, have lower thresholds to open and shorter time limits to remain open.)

She helpfully describes how investigations work through stages, with new investigative methods approved for each

Querying DIVS is, quite literally, the first and most basic thing the FBI does in its investigative sequence. Depending on the kind of information the search returns, an agent will then take the next prescribed step as outlined in the FBI’s Domestic and Investigative Operations Guide (DIOG) until a case is either opened for further investigation, or the matter is resolved in the negative and closed.

She then dismisses the concern that FBI does queries of 702 data at the assessment level without really addressing it.

Much of the criticism of the FBI’s use of 702 centers around the fact that agents can query subjects in their databases even if there is no evidence of criminal wrongdoing. However, as any law enforcement official will tell you, criminals and spies don’t show up on the doorstep of law enforcement with all of their evidence and motives neatly tied up in a bow. Cases begin with leads, tips, or new information obtained in the course of other cases. Often, the discrete pieces of information the FBI receives may not in and of themselves constitute criminal acts – and the identifying information provided to the FBI may be incomplete. However, anytime the FBI receives a credible piece of information that could indicate a potential violation of the law or a threat to national security, it has a legal duty determine whether a basis for further investigation exists. It is for this reason that a query of its existing databases is essential before proceeding further.

Somehow, the necessity of investigating a tip requires not an assessment of the lead itself, but querying a vast data store to see if the lead connects to any other known evidence even if that evidence is not itself evidence of criminal behavior. (One of the reasons FBI does that — which I’ve written about elsewhere — is to make it easier to find informants.)

That logic — which absolutely reflects the logic under which FBI operates — is all the more bizarre given the fact that the FBI is obliged, under the same DIOG Rangappa cites as the basis for the step-by-step development of an FBI case, to always consider using the “least intrusive” means as laid out by this language in the Attorney General Guidelines.

The conduct of investigations and other activities authorized by these Guidelines may present choices between the use of different investigative methods that are each operationally sound and effective, but that are more or less intrusive, considering such factors as the effect on the privacy and civil liberties of individuals and potential damage to reputation. The least intrusive method feasible is to be used in such situations.

DIOG section 4.4, which lays out what least intrusive means, says that “wiretaps … are very intrusive.” It says that “collecting information regarding an isolated event, such as a certain phone number called … is less intrusive or invasive of an individual’s privacy than collecting a complete communications … profile.” It states that, “If, for example, the threat is remote, the individual’s involvement is speculative, and the probability of obtaining probative information is low, intrusive methods may not be justified, and, in fact, may do more harm than good.”

Ultimately, though, the DIOG swallows all these rules by stating that, “FBI employees may use any lawful method allowed, even if intrusive, where the intrusiveness is warranted by the threat to the national security.” The logic must be — probably not born out even by FBI’s limitation to obtaining raw 702 data tied to Full Investigations — that for any person tied to a Full Investigation, any possible tie to an American about whom someone has submitted a tip, national security overrides all FBI’s rules about least intrusive methods.

But nonetheless, the FBI’s own guidelines admit how intrusive it is to start an investigation by looking at entire conversations rather than simply seeing the record of a email sent. That is, however, what the routine practice is.