MMT and Mainstream Economics

Posts in this series. This post begins with links to all posts in this series.

In The Deficit Myth Stephanie Kelton explains in lay terms the fundamental ideas of Modern Monetary Theory and shows that they can be used to organize a economy that works for everyone. Throughout this series I have occasionally pointed to ways that MMT differs from mainstream economics. In this post I will try to get those ideas organized.

1. Elements of Mainstream Economics.

Let’s start with this quote from the J.W. Mason review of the book:

But in my view it’s better—both more accurate and more productive—to see [MMT] as a body of arguments within an older Keynesian tradition of economics. Contrary to the sense you might get from both supporters and detractors, it’s not a crystalline logical structure where, if you remove one piece, the whole thing collapses. Rather, like most emerging bodies of thought, it’s a ramshackle assemblage of parts built at different times for different purposes, tied together with loose solder of association and inference rather than tight bonds of deduction.

The boldfaced part of this sounds to me like a fair description of mainstream economics. We can see some of the assumptions and axioms of mainstream economics in this list by Harvard economist and textbook author N. Gregory Mankiw of ten things economists agree about. The link is a good refresher course in introductory economics.

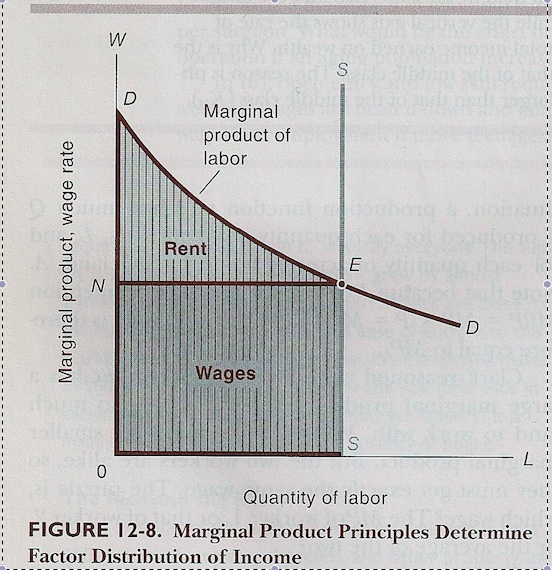

One crucial assumption is that rational people think at the margin. By “rational” Mankiw means “systematically and purposefully doing the best you can to achieve your objectives.” [1] This is a reference to marginal utility theory, invented by the mathematician William Stanley Jevons around 1870. Jevons’ book is premised on the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham. [2] Marginal thinking pervades mainstream economics. [3]

As an example, consider the notion of Pareto Optimality, invented by Vilfred Pareto, another early economist with a STEM background. The idea is that we add up all the individual utilities of all the members of a society at a point in time and get a total. If we change some policy, it will affect the individual utilities. If the new policy makes some people better off and doesn’t make anyone worse off, we approve the policy.

So, for example, suppose a corporation has excess cash. It could distribute the money to shareholders or it could give raises to all the workers who created the excess. Either way is fine under Pareto Optimality. In the real world, the money goes to the shareholders, and the workers are rightly hostile about their stagnant wages. If you don’t like this as a normative principle, you’ll really despise Kaldor-Hicks Optimality.

Other things that went into the early stages of economic theory are based on conditions at the time. That’s why we see the word “markets’ taking a central place. No one thinks that markets of today bear any resemblance to the markets known to Jevons or Adam Smith. It’s also why commodity money, like gold, has a central place, even though the US has only offered fiat money for decades. And it’s one reason we have this mystic reverence for capital and capital accumulation, which we have been taught was the engine of our current prosperity. This reading of history obscures the roles of slavery, government give-aways of land and mineral rights to the wealthy, and the misery of the recessions that unbridled capitalism created.

We have completely forgotten why we have these ideas. We don’t realize that we are centering the ideas of Jeremy Bentham. We never ask why we should prioritize maximizing utility for each individual, or ask ourselves what the balance is between the utility of the day, the decade, or the nation or our children might be. We forget the role of enslavement in the accumulation of capital, and deny the role of government. We ignore the damage capitalism has done to hundreds of millions of us over our history. We don’t question the need for more and more capital accumulation to push the economy where we want it to go. We don’t even ask what ends we want the economy to fulfill. We think and act like we are still on the gold standard.

I realize that many mainstream economists are more or less conscious of all this. But this is the thinking that dominates in our political discourse about the economy. All our politicians, most reporters and pundits (and all right-wing reporters and pundits), and most of us, think and act as if in essentials the “economy” is the same today as it was 150 years ago.

There is a strong tendency in mainstream economics to treat the status quo as if it were the result of the operations of natural laws. This tendency is illustrated in first part of this post.

2. MMT as an alternative.

MMT proceeds from a completely different place. It has no roots in philosophy. It seems to me that MMT is in the tradition of Pragmatism, the American philosophy of Charles Peirce, William James and John Dewey. [4] MMT starts with questions: what is money, and how does it work in our economy? There is no normative principle at work. MMT theorists proceed empirically, studying the way we use money throughout our economy. Money is a thing, and we need to understand its nature and its use. A big part of The Deficit Myth is devoted to examining these questions.

Separate and apart from this inquiry, we need to ask ourselves what we think makes for a good society. This inquiry isn’t about money or the economy, but about our goals. [5] In the US we make these decisions democratically. [6] We elect leaders by majority rule, and we lean on them to legislate and enforce our preferred policies. MMT shows that we can have legislative policies that support our overall desires. That claim, that we can have the things we want, is the real lesson of The Deficit Myth.

Of course, MMT doesn’t attempt to overthrow the entire edifice constructed by mainstream economics. Pragmatic theory says that we only change what we have to as our understanding improves. This means, for example, that ideas formed from an examination of data about other parts of the economy are not necessarily overturned by MMT. But even so, the ideas of MMT are a tool for examining the entire structure.

Conclusion.

Both political parties agree that our society can’t have what we want an need because there is no money, so we must suffer the status quo. Speaker Pelosi tells us she will impose PAY-GO. Joe Biden’s adviser Ted Kaufman says that we can’t do anything because “When we get in, the pantry is going to be bare.” In practice, this means we can only have whatever the richest people think is best for us. It’s not true. Speaking personally, it makes me angry when I see it in practice, long lines at food banks, people forced to risk their health to earn enough to eat, lead-ridden water systems in Flint and elsewhere, to name a few.

We need politicians who can read Kelton’s book. Those politicians need advisers who have studied the expanding literature of MMT. Mainstream economics is a dead end for our nation, and it will take the rich down with the rest of us as the planet catches fire and we suffer one horrible disaster after another.

Note: this is the last post in this series. Please feel free to use the comments to ask any questions or comment on any aspects of MMT.

=======

[Graphic via Grand Rapids Community Media Center under Creative Commons license-Attribution, No Derivatives]

[1] I don’t qualify as rational under this definition. My objectives are rarely systematic, and often I’m not conscious of them. They change from time to time based on my understanding of possibilities and probabilities, as well as contacts with my fellow humans directly and through books. The closer people are to me, the more they have the ability to influence my objectives. Many of the systematic efforts I’ve made failed and others have to be realigned with new and different objectives. And it’s absurd to think that most of my everyday purchases are made with some objective in mind beyond passing fancies. I’m too lazy to change things unless I have to, so often I stay with one system when another would be cheaper and better. And so on.

[2] Jevons’ book, Principles of Economics (1871), is available to read online. It’s an effort to put Bentham’s theories of utilitarianism into the form of a calculus of pleasure and pain. This is from the Preface to the Second Edition:

As to Bentham’s ideas, they are adopted as the starting-point of the theory given in this work, and are quoted at the beginning of chapter ii.

[3] I look at these ideas in several posts, here among others.

[4] I give a short primer on Pragmatism in three posts, here, here, and here.

[5] This question is beyond this series, but I can offer something on the edge of philosophical as a starting place: The Needs Of The Soul, a short essay by Simone Weil. Or listen to a podcast by Partially Examined Life, episode 250.

[6] This is not the place to discuss the problems with our democracy, which I acknowledge are great.