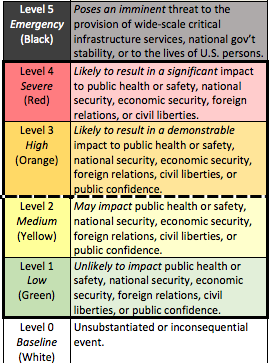

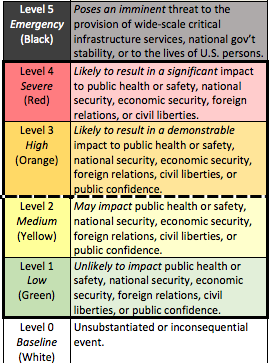

As I  noted yesterday, earlier this week President Obama rolled out a new Presidential Policy Directive, PPD 41, which made some changes to the way the US will respond to cyberattacks.(PPD, annex, fact sheet, guideline) I focused yesterday on the shiny new Cyber Orange Alert system. But the overall PPD was designed to better manage the complexity of responding to cyberattacks — and was a response, in part, to confusion from private sector partners about the role of various government agencies.

noted yesterday, earlier this week President Obama rolled out a new Presidential Policy Directive, PPD 41, which made some changes to the way the US will respond to cyberattacks.(PPD, annex, fact sheet, guideline) I focused yesterday on the shiny new Cyber Orange Alert system. But the overall PPD was designed to better manage the complexity of responding to cyberattacks — and was a response, in part, to confusion from private sector partners about the role of various government agencies.

That experience has allowed us to hone our approach but also demonstrated that significant cyber incidents demand a more coordinated, integrated, and structured response. We have also heard from the private sector the need to provide clarity and guidance about the Federal government’s roles and responsibilities. The PPD builds on these lessons and institutionalizes our cyber incident coordination efforts in numerous respects,

The PPD integrates response to cyberattacks with the existing PPD on responding to physical incidents, which is necessary (actually, the hierarchy should probably be reversed, as our physical infrastructure is in shambles) but is also scary because there’s a whole lot of executive branch authority that gets asserted in such things.

And the PPD sets out clear roles for responding to cyberattacks: “threat response” (investigating) is the FBI’s baby; “asset response” (seeing the bigger picture) is DHS’s baby; “intelligence support” (analysis) is ODNI’s baby, with lip service to the importance of keeping shit running, whether within or outside of the federal government.

To establish accountability and enhance clarity, the PPD organizes Federal response activities into three lines of effort and establishes a Federal lead agency for each:

- Threat response activities include the law enforcement and national security investigation of a cyber incident, including collecting evidence, linking related incidents, gathering intelligence, identifying opportunities for threat pursuit and disruption, and providing attribution. The Department of Justice, acting through the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force (NCIJTF), will be the Federal lead agency for threat response activities.

- Asset response activities include providing technical assets and assistance to mitigate vulnerabilities and reducing the impact of the incident, identifying and assessing the risk posed to other entities and mitigating those risks, and providing guidance on how to leverage Federal resources and capabilities. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), acting through the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC), will be the Federal lead agency for asset response activities. The PPD directs DHS to coordinate closely with the relevant Sector-Specific Agency, which will depend on what kind of organization is affected by the incident.

- Intelligence Support and related activities include intelligence collection in support of investigative activities, and integrated analysis of threat trends and events to build situational awareness and to identify knowledge gaps, as well as the ability to degrade or mitigate adversary threat capabilities. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence, through the Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center, will be the Federal lead agency for intelligence support and related activities.

In addition to these lines of effort, a victim will undertake a wide variety of response activities in order to maintain business or operational continuity in the event of a cyber incident. We recognize that for the victim, these activities may well be the most important. Such efforts can include communications with customers and the workforce; engagement with stakeholders, regulators, or oversight bodies; and recovery and reconstitution efforts. When a Federal agency is a victim of a significant cyber incident, that agency will be the lead for this fourth line of effort. In the case of a private victim, the Federal government typically will not play a role in this line of effort, but will remain cognizant of the victim’s response activities consistent with these principles and coordinate with the victim.

Thus far, this just seems like an effort to stop everyone from stepping on toes, though it also raises concerns for me whether this is the first step (or the public sign) of Obama implementing a second portal for CISA, which would permit (probably) FBI to get Internet crime data directly without going through DHS’s current scrub process. Unspoken, of course, is that necessity for a new PPD means there has been toe-stepping in incident response in the last while, which is particularly interesting when you consider the importance of the OPM breach and the related private sector hacks. Just as one example, is it possible that no one took the threat information from the Anthem hack and started looking around to see where else it was happening.

So yeah, some concerning things here, but I can see the interest in minimizing the toe-stepping as we continue to get pwned in multiple breaches.

Also, there’s no mention of NSA here. Shhhh. They’re here, as soon as an entity asks them for help and (from an intelligence perspective with data laundered through FBI and ODNI and DHS) from an intelligence perspective.

Here’s what I find particularly interesting about all this.

The PPD — along with the fancy Cyber Orange Alert system — came out less than a week after DOJ’s Inspector General released a report on the FBI’s means of prioritizing cyber threats (which is different than cyber attacks). The report basically found that the FBI has improved its cyber response (there’s some interesting discussion about a 2012 reorganization into threat type rather than attack location that I suspect may have implications for both criminal venue and analytical integrity, including for the attack on the DNC server), but that the way in which it prioritized its work didn’t result in prioritizing the biggest threats, in part because it was basically a “gut check” and in part because the ranking process wasn’t done frequently enough to reflect changes in the nature of a given threat (there was a classified example of a threat that had grown but been missed and of conflicting measures in the two ways FBI assesses threats, both of which are likely very instructive). The report does mention the OPM hack as proof that the threat is getting bigger, which does not confirm nor deny that it was one of the classified issues redacted.

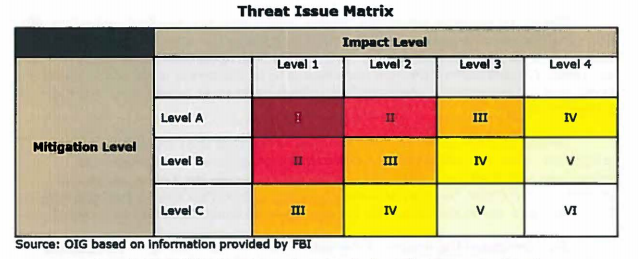

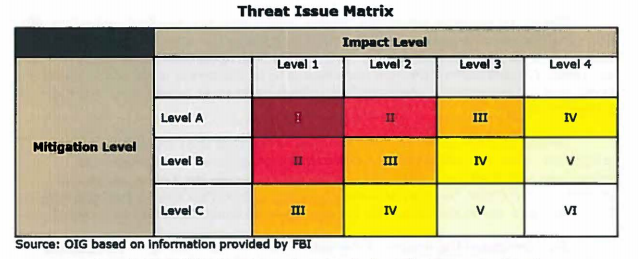

The FBI conducts a bureau-wide Threat Review and Prioritization (TRP) process, of which cyber is a part, which happens to have the same number of outcomes as the PPD 41 does, 6, though it is more of a table cross-referencing impact with mitigation (the colors come from DOJ IG so comparing them would be meaningless).

And the FBI TRP asks some of the same questions as the PPD’s Cyber Orange Alert system does.

The FBI’s Directorate of Intelligence (DI) manages the TRP process and publishes standard guidance for the operational divisions and field offices to use; including the criteria for the impact level of the threat and the mitigation resources needed to address the threat. The FBI impact level criteria attempt to measure the likely damage to U.S. critical infrastructure, key resources, public safety, U.S. economy, or the Integrity and operations of government agencies in the coming ear based upon FBI’s current understanding of the threat issue. Impact level criteria seek to represent the negative consequences of the threat issue, nationally. The impact level criteria include: (1) these threat issues are likely to cause he greatest damage to national interests or public safety in the coming year; (2) these threat issues are likely to cause great damage to national interests or public safety in the coming year; (3) these threat issues are likely to cause moderate damage to national interests or public safety in the coming year; or (4) these threat issues are likely to cause minimal damage to national interests or public safety in he coming year (FBI emphasis added). 12 One FBI official told us that these impact criteria questions, which are developed and controlled by the Directorate of Intelligence, are designed to be interpreted by the operational divisions.

The three levels of mitigation criteria, which also are standard across the FBI, measure the effectiveness of current FBI investigative and intelligence activity based upon the following general criteria: ( 1) effectiveness of FBI operational activities; (2} operational division understanding of the threat issue at the national level; and {3) evolution of the threat issue as it pertains to adapting or establishing mitigation action.

This is the system that people DOJ IG interviewed described as a “gut check.”

While the criteria are standardized, we found that they were inherently subjective. One FBI official told us that the prioritization of the threats was essentially a “gut check.” Other FBI officials told us that the TRP is vague and arbitrary. The Cyber Division Assistant Director told us that the TRP criteria are subjective and assessments can be based on the “loudest person in the room.”

There was some tweaking of this system in March, but DOJ IG said it didn’t affect the findings of this report.

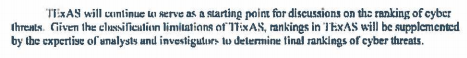

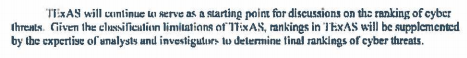

FBI has another newer system called Threat Examination and Scoping (TExAS; it claimed it was far more advanced in its own 9/11 review report a few years back), which they also only use once a year, but which at least is driven by objective questions to carry out the prioritization. DOJ IG basically found this better system suffered the things you always find at FBI: data entry problems, a lack of standard operating procedures, stove-piped management, disconnection from FBI’s other data system. But it said that if TExAS fixed those issues and made it more objective it would be the tool the FBI needs to properly prioritize threats.

There’s one detail of particular interest. The report narrative described one advantage of TExAS as that it could integrate information from other agencies, foreign, or private partners.

According to FBI officials, TExAS has the capability to include intelligence from other agencies, the United States Intelligence Community, private industry, and foreign partners to inform FBI’s prioritization and strategy. For example, a response in TExAS can be supported with documentation from a United States Intelligence Community partner for a threat as to which the FBI lacks visibility. The tool also is capable of providing data visualizations, which can help inform FBI decision makers about prioritizing or otherwise allocating resources toward new national security cyber intrusion threats, or towards national security intrusion threats where more intelligence is needed.

But way down in the appendix, it describes what appears to be this same ability to integrate information on which the “FBI lacks visibility” as a “classification limitation” that requires analysts to review the rankings to tweak them to account for the classified information.

In other words, because of classification issues (see?? I told you NSA was here!!), even the system that might become objective will still be subject to these reviews by analysts who are privy to the secret information.

Now I’m not sure that makes PPD 41’s own prioritization system fatal — aside from the fact that it seems like it will be a gut check, too. Though it does lead me to wonder whether FBI didn’t adequately prioritize some growing threat (cough, OPM) and as a result — the DOJ IG report admits — FBI simply wouldn’t dedicate the resources to investigate it until it really blew up. Under PPD-41, it would seem ODNI would do some of this anyway, which would eliminate some of the visibility problems.

I point all this out, mostly, because of the timing. Last week, DOJ IG said FBI needed to stop gut checking which cyber threats were most important. This week, the White House rolled out a broad new PPD, including a somewhat different assessment system that determines how many federal agencies get to step on cyber-toes.