Dilma Throws Obama a BRIC

I was actually surprised, back in May, when the White House announced a State Visit for Brazil’s President, Dilma Rousseff.

I was actually surprised, back in May, when the White House announced a State Visit for Brazil’s President, Dilma Rousseff.

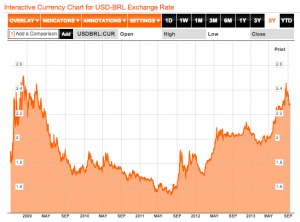

After all, not long after Obama visited Brazil in March 2011, the real started gaining value against the dollar, significantly slowing the boom Brazil had enjoyed in the wake of our crash.

When she was here in April 2012, Dilma explicitly blamed US Quantitative Easing for the reversal in currencies, and suggested the policy was meant to slow growth in countries like Brazil. Before that, Brazil’s boom and its advances in energy independence had put Brazil in a position to assume the global stature a country of its size might aspire to. And Dilma (partly correctly) blamed US actions for undercutting that stature.

I interpreted the State Dinner to be an attempt to woo Brazil away from natural coalitions with the Bolivarist governments of Latin America and the BRICS (Brazil, Russsia, India, China, and South Africa).

Fast forward to today, when the Brazilian government announced that it has postponed the visit that had been scheduled for October 23.

The usual suspects are mocking Dilma’s decision, insisting that everyone spies, and that Brazil is just making a stink for political gain. The White House statement echoes that, suggesting that it was the revelation of US spying, and not the spying itself, that created the problems.

The President has said that he understands and regrets the concerns disclosures of alleged U.S. intelligence activities have generated in Brazil and made clear that he is committed to working together with President Rousseff and her government in diplomatic channels to move beyond this issue as a source of tension in our bilateral relationship.

There is something to that stance. Dilma’s government faces a lot of unrest and the tensions of preparing for the World Cup. The portrayal that the US was taking advantage of Brazil caught her at a politically sensitive time.

All that said, those poo-pooing Brazil’s complaints ignore the specific nature of the spying as revealed. As I noted, even James Clapper’s attempt to respond to concerns raised by the original reports in Brazil didn’t address (and indeed, may have exacerbated) concerns that the US is engaging in financial war, including manipulating its currency to undercut other countries as they rise in relative power. If the US is using its advantages in SIGINT to engage in such financial war, Brazil has every reason to object, because it’s not something Brazil’s currency or telecommunications position make possible.

US disclaimers of industrial espionage no longer matter if the US is collecting SIGINT that would support substantive financial attacks, especially since Clapper in March made it clear the US envisions such attacks (even if they only admit to thinking in defensive terms).