Mankiw’s Principles of Economics Part 4: People Respond to Incentives

The introduction to this series is here.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

The Fourth Principle of Economics, which N. Gregory Mankiw assures us is accepted by almost all economists is: People Respond To Incentives. This is obviously true, so it’s good that almost all economists agree. Neoliberals agree as well; it’s the basis of their understanding of human nature that people respond to money, and not much else.

Here are the examples. When the price of apples goes up, people buy fewer apples, and “…apple orchard owners decide to hire more workers and harvest more apples.” Supply and demand are the direct result of incentives. Taxes can be used as incentives. If the gasoline tax goes up, people drive smaller cars, switch to public transport and buy hybrids. If the price goes high enough, they might even switch to electric cars. Incentives can have unintended consequences. Seat belt laws led to a higher number of accidents, and more accidents involving pedestrians. There are two longer examples, one on changes resulting from the gas price hikes from 2005 to 2008, and one on the way bus drivers are paid in Chile.

It’s no doubt true that generally as prices rise, the amount purchased falls. It’s probably the case that the relationship isn’t continuous. People don’t watch the price of apples at all. When they are at the store or the market to buy they don’t say to themselves “prices are up a penny a pound, so I’ll just buy a bit less.” Instead, they compare apples to other fruits and even vegetables and as long as the prices seem about right, they buy. It takes a pretty good price jump foror people to notice the exact price per pound. On the other hand, maybe people think Fuji’s are about as good as Gala’s, so if one is cheaper, they buy them. Or if one set looks tastier for some reason, they buy those.

The idea that the orchard owners harvest more or less depending on the price seems equally inadequate. Of course, once harvest season is over, there won’t be any more harvesting, so all decisions have to be made during the short season when the apples are at the proper stage of ripeness. If owners think the prices will be higher, maybe they will harvest more. Or, maybe they harvest all they can to protect the trees and the fields, and only sell if the price is right, and feed the rest to the cows. I don’t know enough about running an orchard to have an opinion, but apparently Mankiw does.

The second example, gasoline taxes, supports the idea that demand can be manipulated by society for its own good. I don’t think that was Mankiw’s point though. We return to this idea in Principle 8.

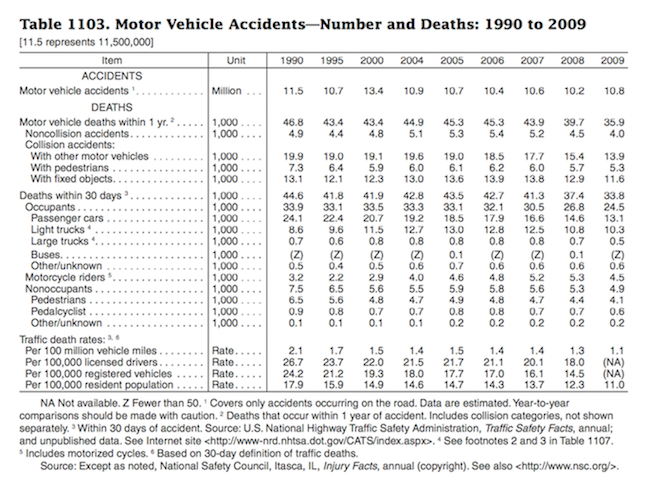

The discussion of seat belt changes shows typical short-term thinking. Assuming that the study Mankiw cites is accurate, and I note he describes it as controversial, in the short term, people acted in a more risky way after the passage of seat belt laws. Here’s a chart from the Statistical Abstract produced by the Census Bureau in 2012 with more recent statistics.

Those statistics tell a different story. They say that the incentive created by one set of changes can be changed once the actual outcomes are known. Cars have become more and more safe, and with the recognition that some of the changes produced bad driving, people were able to find ways of making cars safer in ways that defeated the original incentives.

You’ll note that the deaths of pedestrians were down, too, but that doesn’t tell us much. The number of pedestrians overall may be down.

Finally we have the bus driver example in Chile. It comes from Austan Goolsbee, and explains that drivers paid by the passenger work harder than drivers paid by the hour, including taking the shortest routes between two points when there is a lot of traffic. It doesn’t tell us anything about the response of bus riders who don’t get picked up, oe of other people trying to drive on the same streets as racing bus drivers.

So, everyone agrees that people respond to incentives. The question is how people respond to incentives. Mankiw tells us that economists are social scientists, and their field is centered on understanding human behavior. If these examples are typical of economic thinking, the understanding of behavior is rudimentary and reductive. It’s fair to assume that models built on rudimentary and reductive ideas may produce strange and untrustworthy results.

![[graphic: WSJ.com's July 8th error message]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/WSJ_504Msg_08JUL2015-300x127.jpg)